Celia Gómez-Gordo¹, María Garzón-Polanco¹, Tatiana Fokina¹.

TRANSLATED BY:

Pablo Sánchez-Ayuso², Laura Jiménez-Rivera², Ángel Peinado-Castillo², Pilar Torres-Jiménez², Miguel David Corado-

Palomo², Álvaro López-González².

1. Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Granada (UGR).

2. Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR).

La enfermedad de Lyme (EL) es una zoonosis producida por bacterias del género Borrelia. La EL es una de las enfermedades más frecuentes transmitidas por garrapatas, siendo la más común en Europa y Estados Unidos. La causa por la que es una de las borreliosis más frecuentes es la distribución geográfica de Borrelia, que se correlaciona con las áreas de hábitat de sus vectores, en su mayoría el complejo Ixodes, aunque no es un patógeno exclusivo de este vector. Esto conlleva que algunas regiones del norte de España se posicionen como zonas endémicas de borreliosis, en concreto de EL, debido a las condiciones biogeoquímicas del territorio. No obstante, esta zoonosis está ampliamente extendida por todo el territorio nacional, debido a la presencia ubicua de mamíferos y otros vertebrados portadores del vector, que se conocen con el nombre de huéspedes u hospedadores. A pesar de que la EL es una enfermedad muy frecuente en la Península Ibérica, la heterogeneidad de manifestaciones clínicas y de especies productoras de enfermedad hace que su detección resulte un trabajo complejo, con el consecuente aumento de tiempo diagnóstico y evolución de la enfermedad, implicando la aparición de complicaciones clínicas.

Palabras clave: enfermedad de Lyme, borreliosis, Borrelia, Ixodes.

Keywords: Lyme disease, borreliosis, Borrelia, Ixodes.

INTRODUCCIÓN

La EL es una infección propia de animales que puede ser transmitida a personas, esto es lo que se conoce como zoonosis. Se produce por bacterias del género Borrelia (1), las cuales pertenecen a la clase Spirochaetes (2). Las especies que predominan en España son B. burgdorferi y B. garinii, cuya infección genera síntomas similares en ambos casos (3–5).

La EL se transmite por la inoculación del patógeno Borrelia a través de los quelíceros de la garrapata, que son unos apéndices del aparato bucal de los Ixodes. Estas estructuras generan una lesión en la epidermis del huésped y en dicha lesión se introduce el hipostoma, permitiendo la fijación, e infección del huésped por patógenos presentes en la garrapata (6). En España el principal vector de esta enfermedad es Ixodes ricinus, que es portador de Borrelia burgdorferi, así como de otras especies de este género (4). El tipo de patógeno que causa la infección está en relación con las condiciones bióticas y abióticas del área geográfica que se estudie (7), por lo que es imprescindible conocer las condiciones climáticas y el tipo de animales vertebrados de una región para identificar el agente causante de la infección. Los grandes vertebrados, incluidos los de ámbito ganadero son los huéspedes idóneos para la mayoría de especies de garrapata, siendo sus desplazamientos y migraciones factores posibilitadores de la extensión de las borreliosis entre los territorios adyacentes (7).

Las manifestaciones clínicas de la EL son muy diversas, y la fiebre de origen desconocido no suele ser consecuencia de este tipo de infecciones en población pediátrica (4), habiéndose registrado que la mayoría de estas personas con borreliosis no presenta fiebre, al contrario de las infecciones de otros tipos de patógenos también transmitidos por garrapatas (4). Este hecho obliga a pensar en cualquier variedad de borreliosis ante un cuadro clínico no típico, aún en ausencia de fiebre en niños (8). Es necesario realizar un despistaje de EL ante la presencia de factores de riesgo, ya que existe un infradiagnóstico de esta enfermedad (3). Esta zoonosis es frecuente entre la población pediátrica, apareciendo un pico de incidencia en edad infantil, lo que implica la necesidad de un diagnóstico activo (4).

En esta revisión narrativa se recopila información de varias fuentes para valorar si se realiza un correcto diagnóstico diferencial en presencia o ausencia de factores de riesgo de padecer EL entre las personas susceptibles de ser infectadas por patógenos del género Borrelia.

PREVALENCIA E INCIDENCIA DE LA ENFERMEDAD DE LYME

La incidencia anual de borreliosis de Lyme en España se estima en 0,25 casos por 100.000 habitantes (3). A su vez, la mayor parte de personas infectadas son hombres (3,4), lo que se explica por la mayor actividad laboral de hombres que de mujeres en el ámbito rural (3). Igualmente, la incidencia es mayor en áreas de mayor pluviosidad y bosque bajo, ya que favorece la proliferación de los hospedadores que pueden ser colonizados por la garrapata (4). El clima también es un importante factor en la transmisión del patógeno, ya que se relaciona con el tamaño de las colonias de Ixodes (4). Como resultado de lo anterior, cuantos más factores favorecedores se reúnan en un área, mayor cantidad de garrapatas podrán vivir en ella. Esto explica la diferencia significativa de incidencia que existe entre Asturias, lugar donde es máxima, y las demás comunidades autónomas; a excepción de Ceuta, que también presenta una incidencia superior a la media española (3). Sin embargo, un estudio realizado en pacientes pediátricos en Galicia se obtuvo una incidencia media de 5,5 casos por 100.000 habitantes al año (4). En cuanto a los meses con mayor incidencia de infecciones por Borrelia, los meses cálidos entre junio y octubre, son los que registran una mayor tasa de contagios (3,4). Una de las causas de este incremento en el número de garrapatas en estos meses es un clima más óptimo para su reproducción y un incremento en el número de animales vertebrados (7). A pesar de todo, menos de la mitad de los pacientes recuerdan haber sido picados por una garrapata (3,4,9), siendo esto así porque la picadura de ésta es indolora debido al reducido tamaño de Ixodes (Figura 1) (1,4). Como consecuencia de este hecho, se estima que los datos de prevalencia de la EL en España están infravalorados, ya que para realizar las estadísticas se usan fuentes de información limitadas como el Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos (CMBD), que sólo recoge los casos más graves que han necesitado de tratamiento hospitalario, excluyendo aquellos que han recibido tratamiento exclusivamente en atención primaria o ni siquiera han requerido contacto con el sistema sanitario, siendo esta información también fuertemente dependiente de la calidad del informe médico realizado. A pesar de sus limitaciones, el CMBD permite una estimación de la enfermedad en poblaciones amplias (2,10).

VARIABILIDAD ETIOLÓGICA DE LOS VECTORES

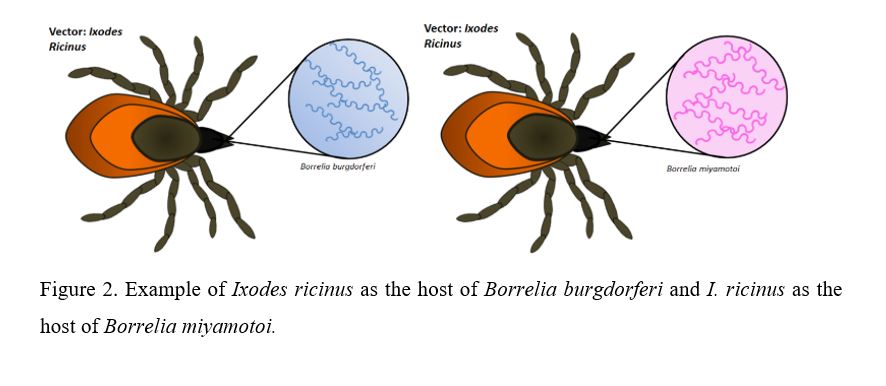

El tipo de patógeno que se transmite en un área geográfica determinada depende de la población de garrapatas de esa zona. Existen varias especies de garrapatas, entre ellas, Ixodes ricinus, que es uno de los tipos predominante en Europa (10), y se ha demostrado que pueden ser colonizadas por diversas especies de Borrelia (Figura 2), entre las que se encuentran: B. burgdorferi, B. garinii, B. miyamotoi, B. afzelii, B. lusitaniae (10).

Para poder estudiar la relación entre los tipos de Borrelia y la prevalencia de infección deben ser tenidos en cuenta tanto los factores bióticos, como los abióticos de la región específica. Se ha demostrado que la relación de las garrapatas con su hábitat depende prioritariamente del clima y de la diversidad de vertebrados que pueden colonizar: a mayor variedad de animales vertebrados más colonias de Ixodes se presentan en la región (7). Se ha estudiado que la presencia de grandes mamíferos en las reservas naturales posibilita el aumento de la población de garrapatas (9). Todo esto condiciona que la mayor tasa de incidencia de EL aparezca en zonas rurales, con gran diversidad de huéspedes vertebrados y en los meses más cálidos del año (3). Con respecto a esto, las zonas del norte de España ofrecen especial interés en cuanto al estudio de la prevalencia de borreliosis en mamíferos presentes, y por ende el posible aumento de poblaciones de garrapatas y contagio de seres humanos.

Esta relación entre hospedadores y garrapatas es fundamental para comprender la circulación de patógenos. Por otra parte, las migraciones de animales vertebrados entre distintas áreas explican la variabilidad de especies de Ixodes en una región: la migración de un portador de determinada especie de Borrelia a un territorio con condiciones ambientales favorables permite su proliferación e introducción en zonas en las que antes no era endémico (7). Una misma especie de vertebrado puede ser colonizado por varios tipos de garrapatas, que a su vez pueden ser huésped de varias especies de Borrelia. En concreto, B. burgdorferi se ha encontrado en muestras de Ixodes ricinus, pero también en Haemaphysalis concinna, Haemaphysalis punctata, Rhipicephalus bursa y Dermacentor reticulatus (9). Esto se explica por el hecho de que haya especies de Borrelia con mayor índice de infectividad que otras (7).

El resultado de estas relaciones inter-especie da una idea de la diversidad de patógenos causantes de EL (7). Según las conclusiones de un estudio en redes, la cantidad de garrapatas y la circulación de los patógenos podrían verse restringidas por una disponibilidad insuficiente de vertebrados (7).

DISTRIBUCIÓN GEOGRÁFICA Y CARACTERÍSTICAS CLIMÁTICAS

La disposición geográfica juega un papel importante en la distribución de esta enfermedad. Así, las zonas del norte y este de España son endémicas del vector, por ende, de las borrelias (11). Especialmente susceptibles son las zonas de montaña y hábitat rural, ya que hay un mayor contacto con mamíferos, así como mayor vegetación y un clima adecuado para la proliferación de los Ixodes (11).

Se han descrito mayor cantidad de diagnósticos entre junio y octubre, ya que existe un desfase de unos meses desde que los pacientes recuerdan el contacto con garrapatas y la aparición de manifestaciones clínicas. En relación con estas conclusiones, en estudios previos se ha observado una mayor prevalencia de infestación por garrapatas en los animales entre mayo y julio (11).

CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL HUÉSPED

Entre la bibliografía no se han encontrado diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre sexo en la zona noreste de España (11), lo que contradice a datos globales de España, en los que sí se han encontrado diferencias estadísticamente significativas, demostrando que es más prevalente en varones (3), por lo que la distribución geográfica ejerce un importante papel a la hora de determinar prevalencias. En concordancia con lo anterior, se han hallado diferencias significativas respecto a la edad, siendo la incidencia de enfermedad de Lyme superior en personas mayores de 65 años (11) aunque según otros estudios aparece otro pico de incidencia entre la población en edad infantil (4).

PRESENTACIÓN CLÍNICA Y TRATAMIENTO

Presentación clínica

La EL presenta una gran variedad de síntomas, entre los más frecuentes se encuentran el eritema migrans (66,7%), la fiebre (44,4%), el dolor en las extremidades (38,9%), la parálisis facial (11,2%), las parestesias (11,2%), el dolor articular (11,1%) (9). Debido a la imprecisión sintomática, el examen físico de los pacientes revela datos no específicos, presentándose síntomas antes del diagnóstico en un 66% de los casos, con una duración promedio de 19,6 +- 9,3 (SD) días. A pesar de la que la mayoría de manifestaciones clínicas no son de gravedad, el 77,2% de los casos requirieron hospitalización, lo que pone de manifiesto la necesidad de un correcto diagnóstico y tratamiento (9).

En resumen, las manifestaciones clínicas más comunes son a nivel neurológico, cutáneo, reumatológico y cardiaco (4).

Estas manifestaciones presentan una evolución temporal en fases: en la primera fase (localizada) la manifestación más frecuente es cutánea, siendo el eritema migrans una manifestación patognomónica de la EL (12) que predomina en la mitad superior del cuerpo en la población pediátrica, mientras que en adultos es más común en la mitad inferior (4). En la segunda fase (diseminada precoz) aparecen síntomas neurológicos y carditis, a su vez, la meningitis es una complicación frecuente en la infección por Borrelia, presentando un predominio de mononucleares y elevación de proteínas en líquido cefalorraquídeo (4). La tercera fase (diseminada tardía) se caracteriza por la presencia de manifestaciones reumáticas crónicas (4).

Cabe destacar el alto porcentaje de pacientes pediátricos con diagnóstico de EL que no presenta fiebre, diferenciando las borreliosis de otras enfermedades transmitidas por garrapatas, en las que sí suele aparecer fiebre recurrente (4).

En cuanto a la neuroborreliosis, afectación neurológica por la EL, la meningitis linfocítica es la manifestación más frecuente, cursando con proteinorraquia y pleocitosis linfomonocitaria. La radiculoneuritis y neuropatía craneal pueden también estar presentes como afectación temprana (13).

Tratamiento

El tratamiento antibiótico es de elección en la EL, existiendo una amplia tasa de respuesta a éste (4). Se emplean antibióticos orales en la primera fase evolutiva de la enfermedad, siendo la doxiciclina para adultos y amoxicilina para niños menores de 8 años o embarazadas las más empleadas. Asimismo, se ha empleado ceftriaxona, cefuroxima y amoxicilina clavulánico, con tasas de respuesta variables (9). En consecuencia, el tratamiento endovenoso se reserva para casos graves de afectación del sistema nervioso central. Debido a la posible cronificación de los síntomas, el tratamiento antibiótico es de larga duración, aunque existe controversia respecto a la duración del mismo (13).

NECESIDAD DE CONFIRMACIÓN DIAGNÓSTICA

Para poder diagnosticar una borreliosis es necesario realizar una confirmación serológica, excepto si el paciente presenta eritema migrans, ya que es un signo patognomónico de dicha enfermedad y, por lo tanto, diagnóstico (4).

Tras la sospecha clínica, hay que confirmar la posible infección mediantes pruebas microbiológicas validadas como: IFI, ELISA (anticuerpos totales, IgG e IgM), CLIA, PCR o cultivo (14). Si se han detectado anticuerpos positivos o son dudosos, por IFI, ELISA o CLIA, estos han de ser confirmados mediante un Western-Blot (WB) (14). Esta confirmación por WB (con los anticuerpos frente a IgG o IgM) es necesaria al ser complicado el serodiagnóstico por ELISA o IFI debido a las reacciones cruzadas. Además, esta prueba permite conocer frente a qué antígenos específicamente ocurre la síntesis de anticuerpos (15).

Un resultado positivo de bandas en el Western-Blot unido a la interpretación de las mismas en función de que antígenos se hayan estudiado, permite conocer si es una infección activa, si ésta es persistente, si el contacto es pasado o si hay reactividad cruzada con otros microorganismos o síndromes infecciosos.

La PCR y cultivo de muestras cutáneas (biopsia) tiene alta rentabilidad en los Centros de Referencia (14), especialmente en las fases precoces de la enfermedad, en los que aún los auto-anticuerpos son negativos.

Para realizar cualquiera de las pruebas anteriores es necesaria una muestra de sangre, lo más habitual, o líquido cefalorraquídeo si presentan síntomas meníngeos o una meningitis ya establecida. Una vez recogidas, estas muestras se envían a estos Centros de Referencia para su estudio (14).

En relación a lo explicado en el apartado de variabilidad etiológica de los vectores y patógenos, se han descrito garrapatas portadoras de otras bacterias, a destacar Borrelia miyamotoi, por lo que a la hora de confirmar el diagnóstico en el laboratorio es necesario tenerlas en cuenta, sobre todo con alta sospecha de EL y siendo las pruebas de laboratorio para B. burgdorferi negativas(10). A pesar de no estar incluidas dentro de los análisis habitualmente realizados, las espiroquetas se pueden observar en un microscopio de campo oscuro (10).

DISCUSIÓN Y CONCLUSIONES

Actualmente, en España, se están confirmando casos de EL por otros patógenos distintos a B. burgdorferi, como B. garinii. Sin embargo, a día de hoy no hay ningún caso confirmado por B. miyamotoi, ya que esta especie no está incluida en las serologías convencionales. Como consecuencia, es necesario elaborar un nuevo protocolo de diagnóstico de EL en el que se incluyan nuevas especies patógenas para evitar el retraso diagnóstico y el mayor índice de complicaciones que implica.

Se ha de incluir en el diagnóstico diferencial de un cuadro clínico sin manifestaciones claras la posibilidad de EL siempre que haya seguridad o sospecha de picadura de garrapata con manifestaciones cutáneas ante un cuadro febril sin un foco claro, o incluso ante un paciente sin presencia de fiebre, y/o síndrome neurológico sin otra explicación. También es necesario realizar un despistaje de borreliosis ante manifestaciones reumáticas o cardiológicas sin diagnóstico claro, ya que podríamos encontrarnos en la fase de diseminación tardía de la EL.

Al ser los grandes mamíferos portadores frecuentes del complejo Ixodes, y, por tanto, de posibles borreliosis, es vital la correcta prevención primaria, desde el ámbito veterinario con la inspección de los animales de ganadería y domésticos. Al disminuir el número de huéspedes susceptibles, mediante una adecuada desparasitación, las colonias de garrapatas se reducirán de manera notoria. Sería necesaria la creación de campañas de desparasitación externa de animales de granja y domésticos, disminuyendo así uno de los factores de riesgo más importantes, que es el trabajo en ganadería.

Además, es necesario realizar campañas de prevención primaria en zonas endémicas rurales, especialmente en zonas de bosque bajo, ya que las circunstancias son favorables a las picaduras, que incluyan recomendaciones para evitar el contacto con la garrapata, especialmente dirigidas a turistas y ciudadanos locales no acostumbrados al campo. Algunas medidas a tomar son: el uso de prendas de vestir adecuadas, evitando llevar las piernas y pies al descubierto, la utilización de pantalón largo y el uso de zapato cerrado. Por otra parte, es necesario difundir la necesidad de acudir al médico tras la picadura de una garrapata.

Es importante, a su vez, tener en cuenta el área geográfica en la que nos encontramos, en el ambiente en el que vive nuestro paciente y la época del año en la que estemos, considerándolos posibles factores de riesgo de sufrir una picadura de garrapata.

En esta línea, una correcta vigilancia epidemiológica veterinaria, especialmente en el ámbito ganadero y una adecuada descripción de las zonas endémicas, facilita el acceso a esta información por parte del personal sanitario, en beneficio de un correcto diagnóstico. En este aspecto, un sistema de notificación de casos sería beneficioso, registrando de forma exhaustiva las sospechas diagnósticas y los diagnósticos confirmados, y dando una idea más precisa de la prevalencia de la EL en España.

DECLARACIONES:

Agradecimientos

Este trabajo forma parte del Proyecto de Innovación Docente coordinado entre la Facultad de Medicina y la Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación de la Universidad de Granada (UGR), bajo el marco del Plan FIDO 2018-2020 de la UGR (código 563).

Consideraciones éticas

Este estudio no requirió la aprobación de ningún comité ético

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este artículo declaran no presentar ningún tipo de conflicto de interés.

Financiación

No se ha recibido ningún tipo de financiación para la producción de este artículo.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- Enfermedad de Lyme: MedlinePlus en español [Internet]. [citado: 2 marzo 2020]. Disponible en: https://medlineplus.gov/spanish/lymedisease.html

- Taxonomy browser (Borrelia) [Internet]. [citado: 2 marzo 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=138

- Bonet Alavés E, Guerrero Espejo A, Cuenca Torres M, Gimeno Vilarrasa F. Incidencia de la enfermedad de Lyme en España. Medicina Clinica. 2016 15;147(2):88–9.

- Vázquez-López ME, Pérez-Pacín R, Díez-Morrondo C, Díaz P, Castro-Gago M. Lyme disease in paediatrics. Anales de Pediatria. 2016 1;84(4):234–5.

- Portillo A, Santibáñez S, Oteo JA. Enfermedad de Lyme. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin [Internet]. 2014 [citado: 2 marzo 2020];32(Supl 1):37–42. Disponible en: http://zl.elsevier.es

- Estrada-Peña A. CLASE ARACHNIDA Orden Ixodida: Las garrapatas. Revista IDE@-SEA, no [Internet]. [citado: 2 marzo 2020];13:1–15. Disponible en: www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@

- Estrada-Peña A, de la Fuente J. Host Distribution Does Not Limit the Range of the Tick Ixodes ricinus but Impacts the Circulation of Transmitted Pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology [Internet]. 2017 Oct 11 [citado: 2 marzo 2020];7(OCT):405. Disponible en: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00405/full

- Blanco-Vidal MJ, Guio-Carrión L, Montejo-Baranda JM, Iraurgu-Arcarazo P. Neuroborreliosis: experiencia de 10 años en un hospital terciario del norte de España. Revista Española de Quimioterapia [Internet]. 2017 [citado: 22 marzo 2020];30(3):234–5. Disponible en: https://medes.com/publication/122555

- Espí A, del Cerro A, Somoano A, García V, M. Prieto J, Barandika JF, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence and diversity in ticks and small mammals in a Lyme borreliosis endemic Nature Reserve in North-Western Spain. Incidence in surrounding human populations. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2017 1;35(9):563–8.

- Palomar AM, Portillo A, Santibáñez P, Santibáñez S, Oteo JA. Borrelia miyamotoi: Should this pathogen be considered for the diagnosis of tick-borne infectious diseases in Spain? Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica [Internet]. 2018 1 [citado: 22 marzo 2020];36(9):568–71. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29187292

- Vázquez-López ME, Pego-Reigosa R, Díez-Morrondo C, Castro-Gago M, Díaz P, Fernández G, et al. Epidemiología de la enfermedad de Lyme en un área sanitaria del noroeste de España. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2015 1;29(3):213–6.

- Comunicación Atención a pacientes con problemas infecciosos | Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN | Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN [Internet]. [citado: 2 marzo 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-medicina-familia-semergen-40-congresos-39-congreso-nacional-semergen-55-sesion-atencion-pacientes-con-problemas-infecciosos-3726-comunicacion-eritema-migrans-44414

- Enfermedad de Lyme – Diagnóstico y tratamiento – Mayo Clinic [Internet]. [citado: 2 marzo 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.mayoclinic.org/es-es/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374655

- Decálogo SEIMC de recomendaciones sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la infección por Borrelia burgdorferi-E. de Lyme. Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2019.

- del Carmen Maroto Vela M, Gutiérrez Fernández J. Diagnóstico de laboratorio de la infección por Borrelia burgdorferi. Control de calidad SEIMC. Disponible en: http://www.aefa.es/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Diagnostico-de-laboratorio-de-infeccion-por-borrelia.pdf

Lyme Disease in Spain: An Overview

Lyme disease (LD) is a zoonosis caused by bacteria of the genus Borrelia. LD is one of the most frequent diseases transmitted by ticks, being the most common in Europe and the United States. The geographical distribution of Borrelia is the reason why this is one of the most common borreliosis, which is also related to the habitat of its vectors (mostly the genus Ixodes). However, Borrelia is not the sole pathogen of this vector. As a consequence, some regions of northern Spain are considered to be borreliosis endemic areas, particularly of LD, due to the biogeochemical conditions of the area. Nevertheless, this zoonosis is widely spread throughout the country, due to the ubiquitous presence of mammals and other vertebrates carrying the vector (hosts). Although LD is very frequent across the Iberian Peninsula, the heterogeneity of clinical manifestations and vectors complicates its detection. Consequently, diagnosis is delayed and the disease develops, which leads to clinical complications.

Keywords: Lyme disease, borreliosis, Borrelia, Ixodes.

INTRODUCTION

Lyme disease (LD) is an infection that mainly affects animals, but can also be transmitted to humans (i.e. a zoonosis). This disease is caused by bacteria of the genus Borrelia (1), which belong to the phylum Spirochaetes (2). In Spain, the predominant species are B. burgdorferi and B. garinii, whose infections cause similar symptoms (3-5).

LD is transmitted by inoculation of the pathogen Borrelia through the chelicerae of the tick, which are appendages of the genus Ixodes mouthparts. These chelicerae cause a lesion in the epidermis of the host and, as a result, the hypostome is pulled into the skin, allowing its attachment. This leads to the infection of the host due to the pathogens carried by the tick (6). In Spain, the main vector of LD is Ixodes ricinus, which carries Borrelia burgdorferi and other species of this genus (4). The type of pathogen causing the infection is related to the biotic and abiotic conditions of the geographical area being studied (7). Therefore, it is essential to know both the climatic conditions and the type of vertebrates living in a region in order to identify the agent of the infection. Large vertebrates, including livestock, are the ideal hosts for most tick species. Furthermore, the movements and migrations of livestock are one of the factors that enables the spread of borrelioses in neighboring areas (7).

Although LD presents a wide variety of clinical manifestations, fever of unknown origin is not usual in this type of infections in a pediatric population (4). In fact, it has been reported that most people with borreliosis do not show fever as a symptom, unlike infections caused by other types of pathogens that are also transmitted by ticks (4). In the case of an atypical clinical picture, various types of borreliosis should be considered, even in the absence of fever in children (8). Since there is an under-diagnosis of LD, the presence of risk factors makes it necessary to perform a screening for the disease (3). This zoonosis is frequent among the pediatric population, with a peak incidence for children between 3 and 12 years old, which implies the need for an active diagnosis (4). This literature review collects data from a variety of sources in order to evaluate whether a correct differential diagnosis is performed in the presence or absence of risk factors for LD among people susceptible of being infected by pathogens of the genus Borrelia.

LYME DISEASE PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

The incidence of Lyme borreliosis in Spain is estimated at 0.25 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year (3). Men are the most affected by this disease (3, 4), as they are more engaged in agricultural activities than women (3). At the same time, the incidence rises in high rainfall and coppice areas, since they favor the proliferation of hosts that can be colonized by ticks (4). Climatic factors are also important in pathogen transmission regarding its connection with the size of Ixodes colonies (4). Thus, more tick will live in areas with the most favorable factors. This explains the significant difference in incidence found between Asturias (maximum incidence) and the rest of autonomous communities, with the exception of Ceuta, where the rate is also higher than the Spanish average(3). Nonetheless, a study conducted on pediatric population in Galicia showed an average incidence of 5.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year (4). In terms of incidence throughout the year, a higher infection rate of Borrelia is reported during the warmest months, between June and October (3,4). The increase on the number of ticks in these months is associated with both the favorable climate for their breeding and the rise in the amount of possible vertebrate hosts (7). In spite of this, due to the small size of Ixodes (Figure 1) (1,4), the tick bite is painless and less than half of the patients remembers being bitten (3,4,9). Consequently, it is estimated that the LD prevalence data in Spain are underrated due to the limitation of its sources, such as the Spanish Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS). This data set exclusively gathers information of inpatient treatments and excludes minor cases treated by primary health care services, and those without any clinical contact. This information strongly depends on the quality of the medical report. Regardless of its limitation, the MBDS allows the estimation of prevalence in large populations (2, 10).

ETIOLOGICAL VARIABILITY OF VECTORS

Pathogen transmission in a certain geographic area will depend on the tick population of that specific region. There are several tick species, including Ixodes ricinus, one of the prevailing species in Europe (10). There is evidence that Ixodes ricinus can be colonized by different Borrelia species (Figure 2) such as B. burgdorferi, B. garinii, B. miyamotoi, B. afzelii, and B. lusitaniae (10).

Biotic and abiotic factors of a specific area have to be considered in order to study the connection between types of Borrelia and infection prevalence. It has been proved that the relationship of ticks within their habitat mainly depends on climate and the diversity of vertebrates they can colonize. As a consequence, the greater the variety of vertebrates, the more colonies of Ixodes will live in that specific region (7). Furthermore, studies reveal that the presence of large mammals living in nature reserves enables tick population to increase (9). These conditions lead to a higher incidence rate of LD in rural areas with high diversity of host vertebrates during the warmest period of the year (3). In this respect, the northern regions of Spain are of great interest in terms of studying the prevalence of borreliosis in present mammals, and therefore a possible increase of tick population and human infection.

The relationship between hosts and ticks (interspecies relationship) is essential in order to understand pathogen transmission. In contrast, migration of vertebrates among different areas may explain the variability of species of genus Ixodes within a certain region. Thus, the migration of vertebrates which carry a particular species of Borrelia to an environmentally optimal region may allow this particular species to proliferate and develop in areas where they were not previously endemic (7).

The same species of vertebrates can be colonized by different types of ticks, which in turn can be hosts to different species of Borrelia. In fact, B. burgdorferi has been found not only in samples of Ixodes ricinus, but also in Haemaphysalis concinna, Haemaphysalis punctata, Rhipicephalus bursa and Dermacentor reticulatus (9). This can be explained by the fact that some Borrelia present a higher infectivity rate than others (7).

These interspecies relationships illustrate the diversity of pathogens which cause LD (7). According to a study which used network analysis, the amount of ticks and pathogen transmission could be limited by insufficient availability of vertebrates (7).

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION AND CLIMATIC CHARACTERISTICS

Geography plays an important role in the distribution of this disease. Thus, eastern and northern regions of Spain are endemic zones of the vector, and consequently, of Borrelia (11). Rural and mountain areas are highly susceptible for three reasons: contact with mammals is more frequent, there is more vegetation, and the climate is appropriate for Ixodes to spread (11).

A greater number of diagnoses has been reported between June and October, as there is a time lag of some months since patients remember being in contact with ticks and the appearance of clinical manifestations. Regarding these conclusions, a higher prevalence of tick infestation in animals between May and July has been observed (11).

HOST CHARACTERISTICS

No statistically significant differences regarding sex in the northeast area of Spain have been observed in the literature (11). This stands in contradiction to other data from Spain, which shows that it is more frequent among men (3). Hence, the geographical distribution is an important factor in determining the prevalence of LD. Significant differences have been found with regard to age, being the incidence of LD higher in people over 65 (11). Nevertheless, other studies report another peak incidence among children aged between 3 and 12 (4).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND TREATMENT

Clinical Presentation

LD presents a wide variety of symptoms, being erythema migrans (66.7%), fever (44.4%), extremities pain (38.9%), facial palsy (11.2%), paresthesias (11.2%), and joint pain (11.1%) (9) among the most frequent. Due to these non-specific symptoms, physical examination of patients does not reveal precise data. Symptoms appear before diagnosis in 66% of cases, with an average duration of 19.6 ± 9.3 (SD) days. Even though most clinical manifestations are not severe, 77.2% of cases required hospitalization, which highlights the need for a correct diagnosis and treatment (9). In short, the most common clinical manifestations are neurological, cutaneous, musculoskeletal and cardiac (4). These manifestations present a temporal progression through several LD stages. In the first stage (early localized LD), the most frequent manifestation is cutaneous, being erythema migrans a pathognomonic manifestation of the disease (12). In the pediatric population this symptom predominates in the upper half of the body, whereas in adults it is more common in the lower half (4). In the second stage (early disseminated LD), neurological symptoms and carditis appear. Furthermore, meningitis is a frequent complication caused by Borrelia infection, presenting a predominance of mononuclear cells and an increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein concentration. The third stage (late disseminated LD) is characterized by the development of chronic rheumatic conditions (4).It should also be noted that there is a high percentage of pediatric patients diagnosed with LD that do not develop a fever. This distinguishes borrelioses from other tick-borne diseases, which usually present recurrent fever.

With regard to neuroborreliosis, i.e., neurological involvement in LD, lymphocytic meningitis is the most usual manifestation, along with an increase in CSF proteins and lymphomonocytic pleocytosis. Radiculoneuritis and cranial neuropathy can also be present as early manifestations of the disease (13).

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy is the treatment choice for LD and there is a high response rate to it (4). Oral antibiotics are used in the early stages of the disease. Doxycycline is mostly employed in adults and amoxicillin in children under 8 and pregnant women. Moreover, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid have also been used with variable response rates (9). Intravenous treatment is reserved for severe cases of central nervous system involvement. Due to a possible chronification of symptoms, antibiotic therapy is long-lasting, although there is controversy regarding its duration (13).

NEED FOR DIAGNOSIS CONFIRMATION

Serological confirmation is necessary in order to establish a diagnosis of borreliosis, except in patients with erythema migrans, a pathognomonic sign of LD. In cases of clinical suspicion, the potential infection is to be confirmed through validated microbiological assays such as: IFA, ELISA (total antibodies, IgG and IgM), CLIA, PCR or culture (14). If positive or borderline antibodies are detected by IFA, ELISA or CLIA, these are to be confirmed by a Western blot (WB) assay (14). Due to the crossed reactions in ELISA or IFA serodiagnosis, a confirmation by WB (antibodies against IgG or IgM) is necessary. In addition, WB helps to know the specific antigens the antibody synthesis is directed towards.

Both a positive WB and the interpretation of the bands used on it (which depend on the analyzed antigens) are of great importance. This would help to know whether it is an active, persistent or past infection, and whether there are any infectious syndromes or cross-reactivity with other microorganisms.

PCR and culture of skin samples (skin biopsy) are extremely cost-effective in Reference Centers (14). This cost-effectiveness applies to the early stages of the disease, when patients still have negative auto-antibodies.

Blood samples are usually required for the above-mentioned assays, whereas CSF is required in cases involving signs of meningeal irritation or confirmed meningitis. Once the samples are collected, they are sent to the Reference Centers for analysis (14).

As previously explained in the section about the etiological variability of vectors and pathogens, ticks also carry other bacteria, especially Borrelia miyamotoi. To confirm a laboratory diagnosis, the presence of Borrelia miyamotoi must also be considered. This mainly applies to cases with a high level of suspicion for diagnosing LD, but testing negative for B. burgdorferi (10). Despite not being examined in conventional assays, spirochetes can be observed by darkfield microscopy (10).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Some LD cases caused by other pathogens different from B. burgdorferi such as B. garinii are currently being reported in Spain. Nevertheless, there are not any confirmed cases of B. Miyamotoi up until now, since this species is not included into the conventional serologies. As a consequence, a new diagnostic protocol for LD is required, including new pathogen species to avoid delay in the diagnosis as well as the higher complication rate this inevitably implies.

In the differential diagnosis of a clinical picture with no obvious manifestations, LD should be considered as a possibility in patients with skin manifestations caused by confirmed or suspected tick-bite. This applies to cases involving no febrile clinical picture or a febrile clinical picture with no obvious origin, and/or to cases involving neurological syndrome without further explanation. A borreliosis screening is also required in cases involving musculoskeletal or cardiac manifestations with no obvious diagnosis, since patients may be in the late disseminated LD stage.

Large mammals are the main carriers of the genus Ixodes and, consequently, of potential borrelioses. Thus, a correct primary prevention by performing tests of livestock and household pets in the veterinary field is fundamental. Reducing the number of susceptible hosts (by means of a proper parasite treatment) will result in reducing the number of tick colonies. In addition, creating campaigns for the external parasite treatment of these animals would help to decrease the risk of livestock work, which is one of the main risk factors.

Primary prevention campaigns are also necessary in rural endemic areas, especially in coppice areas where climatic conditions are favorable for tick-bites. The campaigns should include recommendations to avoid human-tick contact, in particular for tourists and locals who are not used to the countryside. These recommendations should focus on wearing appropriate clothes such as trousers and closed shoes, so that the legs and feet are not exposed to the tick-bites. Furthermore, it is necessary to raise awareness on the importance of seeing a doctor after a tick-bite. The geographical area and the environment in which the patient lives, as well as the season of the year, can also be considered risk factors for a tick-bite.

Both a correct veterinary epidemiological surveillance (mainly focused on the livestock field) and an adequate description of the endemic areas facilitate the access to these data for medical personnel, facilitating a correct diagnosis. I A notification system of LD cases in which confirmed and suspected cases can be exhaustively registered would also be beneficial. Thus, the prevalence of LD in Spain could be determined more precisely.

STATEMENTS:

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the Teaching Innovation Project coordinated between the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting of the University of Granada (UGR), within the framework of the FIDO Plan 2018-2020 of the UGR (code 563).

Ethical concerns

This paper did not require the approval of any ethics committee.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for the production of this paper.

REFERENCES

- Enfermedad de Lyme: MedlinePlus en español [Internet]. [Last access: 2 March 2020]. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/spanish/lymedisease.html

- Taxonomy browser (Borrelia) [Internet]. [Last access: 2 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=138

- Bonet Alavés E, Guerrero Espejo A, Cuenca Torres M, Gimeno Vilarrasa F. Incidencia de la enfermedad de Lyme en España. Medicina Clinica. 2016 15;147(2):88–9.

- Vázquez-López ME, Pérez-Pacín R, Díez-Morrondo C, Díaz P, Castro-Gago M. Lyme disease in paediatrics. Anales de Pediatría. 2016 1;84(4):234–5.

- Portillo A, Santibáñez S, Oteo JA. Enfermedad de Lyme. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin [Internet]. 2014 [Last access: 2 March 2020];32(Supl 1):37–42. Available at: http://zl.elsevier.es

- Estrada-Peña A. CLASE ARACHNIDA Orden Ixodida: Las garrapatas. Revista IDE@-SEA, no [Internet]. [Last access: 2 March 2020];13:1–15. Available at: www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@

- Estrada-Peña A, de la Fuente J. Host Distribution Does Not Limit the Range of the Tick Ixodes ricinus but Impacts the Circulation of Transmitted Pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology [Internet]. 2017 Oct 11 [Last access: 2 March 2020];7(OCT):405. Available at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00405/full

- Blanco-Vidal MJ, Guio-Carrión L, Montejo-Baranda JM, Iraurgu-Arcarazo P. Neuroborreliosis: experiencia de 10 años en un hospital terciario del norte de España. Revista Española de Quimioterapia [Internet]. 2017 [Last access: 22 March 2020];30(3):234–5. Available at: https://medes.com/publication/122555

- Espí A, del Cerro A, Somoano A, García V, M. Prieto J, Barandika JF, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence and diversity in ticks and small mammals in a Lyme borreliosis endemic Nature Reserve in North-Western Spain. Incidence in surrounding human populations. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2017 1;35(9):563–8.

- Palomar AM, Portillo A, Santibáñez P, Santibáñez S, Oteo JA. Borrelia miyamotoi: Should this pathogen be considered for the diagnosis of tick-borne infectious diseases in Spain? Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica [Internet]. 2018 1 [Last access: 22 March 2020];36(9):568–71. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29187292

- Vázquez-López ME, Pego-Reigosa R, Díez-Morrondo C, Castro-Gago M, Díaz P, Fernández G, et al. Epidemiología de la enfermedad de Lyme en un área sanitaria del noroeste de España. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2015 1;29(3):213–6.

- Comunicación Atención a pacientes con problemas infecciosos | Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN | Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN [Internet]. [Last access: 2 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-medicina-familia-semergen-40-congresos-39-congreso-nacional-semergen-55-sesion-atencion-pacientes-con-problemas-infecciosos-3726-comunicacion-eritema-migrans-44414

- Enfermedad de Lyme – Diagnóstico y tratamiento – Mayo Clinic [Internet]. [Last access: 2 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/es-es/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374655

- Decálogo SEIMC de recomendaciones sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la infección por Borrelia burgdorferi-E. de Lyme. Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2019.

- del Carmen Maroto Vela M, Gutiérrez Fernández J. Diagnóstico de laboratorio de la infección por Borrelia burgdorferi. Control de calidad SEIMC. Available at: http://www.aefa.es/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Diagnostico-de-laboratorio-de-infeccion-por-borrelia.pdf

AMU 2020. Volumen 2, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

16/03/2020 06/04/2020 29/05/2020

Cita el artículo: Gómez-Gordo C, Garzón-Polanco M, Fokina T. Enfermedad de Lyme en España: una visión global. AMU. 2020; 2(1):6-17