Regina Gálvez-López ¹ , Marta Rodríguez-Camacho ¹ , Andrés Soriano-Mateos ¹ , Eloi Querol-Carranza ¹

1 Estudiante del Máster en Neurociencias Básicas Aplicadas y Dolor de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

TRANSLATED BY:

Julia Cervilla-Carrión ² , Andrea Martín-Manzano ² , María Luisa Martín-Vázquez ² , Cristina de-la-Torre-Sánchez ² , Carolina Sobrino-Cano ² , Rocío Soto-García ²

2 Student of the BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (UGR)

El dolor neuropático es un tipo de dolor de difícil manejo con una prevalencia próxima al 10% de la población. Actualmente, existen varios fármacos aprobados para su tratamiento agrupados en distintas líneas.

Sin embargo, la eficacia farmacológica es limitada en un número significativo de pacientes, por lo que es necesario desarrollar nuevas estrategias terapéuticas. Varias moléculas se encuentran en fases iniciales de ensayos clínicos en humanos, muchas de las cuales están demostrando resultados esperanzadores. Por otra parte, el conocimiento cada vez más preciso de las distintas vías moleculares implicadas en el dolor neuropático está promoviendo el desarrollo de nuevas moléculas con acción sobre potenciales dianas terapéuticas. Algunos de estos agentes se están ensayando en modelos animales y muestran una significativa potencia analgésica. Por último, el papel del tratamiento no farmacológico en el dolor neuropático, mediante alternativas como la radiofrecuencia, la estimulación o los bloqueos nerviosos, está cobrando una relevancia cada vez mayor en la práctica clínica. El objetivo de este trabajo es revisar el statu quo del tratamiento del dolor neuropático en la actualidad, repasando los fármacos aprobados a día de hoy y sus mecanismos de acción principales, y poniendo especial interés en algunas de las moléculas más novedosas que se encuentran en ensayo clínico en humanos y en desarrollo en modelos animales. Además, se recogen algunas de las estrategias no farmacológicas más relevantes en el manejo del dolor neuropático en la actualidad.

Palabras clave: dolor neuropático, nuevos fármacos, tratamiento farmacológico, tratamiento no farmacológico,

ensayo clínico.

Keywords: neuropathic pain, new agents, pharmacological treatment, non-pharmacological treatment, clinical trial.

- Introducción

El dolor neuropático (DN) está causado por una enfermedad o lesión directa del sistema nervioso central o periférico y abarca una amplia casuística etiológica (1,2). Aunque existen dificultades para la determinación de la prevalencia del DN, esta se estima en un 7-10% de la población, siendo más frecuente en mujeres y en mayores de 50 años (2). Las regiones más frecuentemente afectadas son la cervical, lumbar, miembros inferiores y superiores (3). Entre las patologías que se asocian con mayor frecuencia a este tipo de dolor, destacan las neuropatías periféricas, la neuralgia postherpética, la lesión traumática del nervio, la lesión medular, la esclerosis múltiple, el ictus y diversos tipos de cáncer (3).

La complejidad que entraña el tratamiento del DN, considerado por muchos como uno de los síndromes dolorosos más difíciles de manejar (2), ha motivado el desarrollo de numerosos ensayos clínicos (EC) y metanálisis, así como de guías clínicas como la guía de la International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (4). De acuerdo con la evidencia científica y las guías de buena práctica, el tratamiento farmacológico en el DN suele pautarse siguiendo distintas líneas, en cada una de las cuales están disponibles varios grupos farmacológicos (5). Sin embargo, en un número significativo de pacientes, el alivio obtenido es limitado tras agotar las líneas farmacológicas.

Actualmente, varios fármacos destinados al tratamiento del DN se encuentran en fases iniciales de EC, con resultados prometedores en muchos casos (6,7). Por otra parte, se han propuesto potenciales dianas terapéuticas basadas en la mejor comprensión de la fisiopatología del DN y en los resultados obtenidos en estudios con modelos animales (8). Finalmente, es necesario tener en cuenta que el tratamiento y manejo del DN incluye medidas no farmacológicas, y que el papel que están cobrando algunas terapias como la estimulación o el bloqueo nervioso es cada vez más relevante (9).

El propósito de este artículo es revisar el statu quo del tratamiento del DN atendiendo a las últimas guías clínicas internacionales, los tratamientos con mejores resultados en fases avanzadas de EC y el desarrollo experimental de fármacos en modelos animales. Además, se revisarán algunas de las potenciales dianas terapéuticas que se han propuesto en los últimos años.

- Tratamiento farmacológico del dolor neuropático

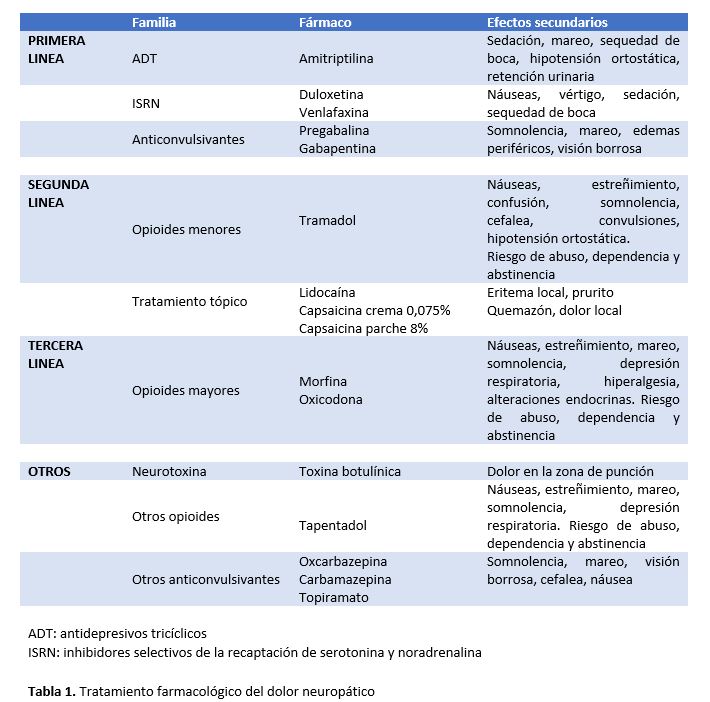

En lo que respecta al manejo farmacológico del DN, distintas líneas de tratamiento han demostrado dar buenos resultados, siendo de especial interés los anticonvulsivantes, antidepresivos tricíclicos (ADT) e inhibidores selectivos de la recaptación de serotonina y noradrenalina (ISRN).

- Fármacos de primera línea

En este grupo figuran los ADT (amitriptilina), que actúan inhibiendo la recaptación de serotonina y noradrenalina, aumentando el control descendente inhibitorio del dolor (10). No obstante, también actúan sobre el canal de sodio, receptores beta-2-adrenérgicos y receptores NMDA, por lo que producen efectos secundarios como sedación, mareo, sequedad de boca e hipotensión ortostática (5). Por otro lado, los ISRN (duloxetina y venlafaxina) también se emplean como terapia de primera línea, con buenos resultados en muchos casos, siendo su efecto adverso más frecuente las náuseas (11). Por último, los anticonvulsivantes (pregabalina y gabapentina) han demostrado ser igualmente eficaces en el manejo del DN. Actúan reduciendo la entrada de calcio en el asta dorsal de la médula, disminuyendo el proceso de sensibilización central (10). Suelen producir somnolencia, mareo y edemas, motivo por el que se recomienda iniciar el tratamiento a dosis bajas (5,11).

- Fármacos de segunda línea

Dentro de los fármacos que suelen emplearse en el tratamiento del DN sin ser de primera elección, se encuentra el tramadol, un opioide menor que actúa sobre el receptor mu como agonista débil y además tiene cierto efecto ISRN. Debido al riesgo de dependencia y abuso, así como de náuseas, confusión, somnolencia y disminución del umbral epileptógeno, conviene emplearlo con cautela (5,11,12).

Otros fármacos de segunda elección, especialmente en el DN periférico, son los agentes tópicos, como la lidocaína al 5% en parches transdérmicos, que bloquea el canal de sodio y disminuye la despolarización neuronal, o la capsaicina al 0,075% en crema o al 8% en parches, que desensibiliza el receptor vaniloide TRPV1 e interfiere en la señalización del dolor (1,5).

- Fármacos de tercera línea

Los opioides mayores, como la oxicodona y la morfina, han sido recientemente desplazados desde el primer y segundo escalón al tercero (12), debido sobre todo a sus potenciales efectos adversos, riesgos y necesidad de monitorización cuando se emplean en el tratamiento del DN. Estos opioides pueden producir abstinencia, dependencia y abuso en mayor medida que el tramadol. Además, pueden acompañarse de náuseas, estreñimiento, somnolencia, depresión respiratoria, y a la larga, de hiperalgesia y alteraciones endocrinas (5,11).

- Fármacos de cuarta línea

Aunque probablemente algunos sean efectivos en grupos concretos de pacientes, las recomendaciones existentes en DN para los demás tratamientos farmacológicos son débiles o no concluyentes (1). En este grupo figurarían otros anticonvulsivantes (oxcarbazepina, topiramato), otros opioides mayores (tapentadol) y la toxina botulínica, entre otros (11,12).

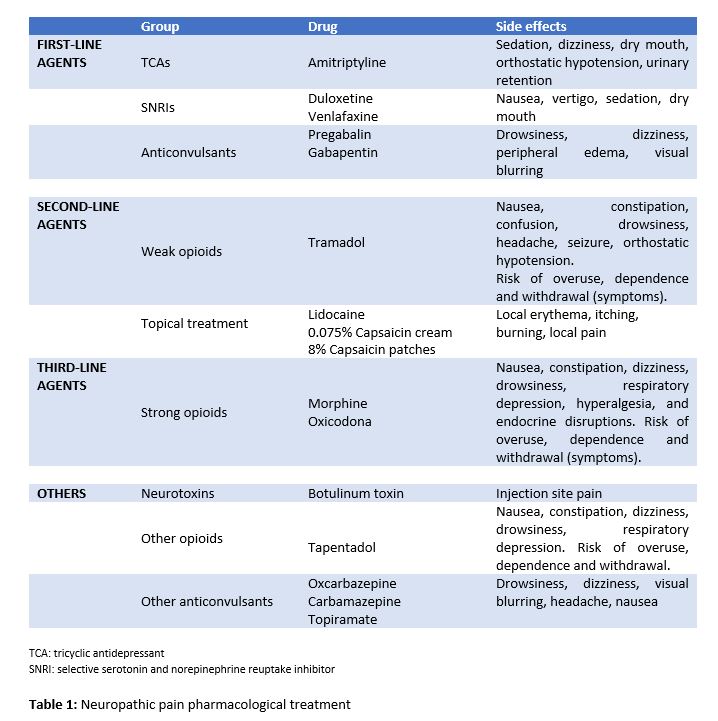

Pese a las numerosas líneas de tratamiento disponibles, los fármacos más empleados para tratar el DN presentan una eficacia limitada, además de efectos secundarios por su uso continuado (Tabla 1), motivo por el que la validación de nuevos fármacos y el estudio de potenciales dianas terapéuticas resulta cada vez más necesario (13).

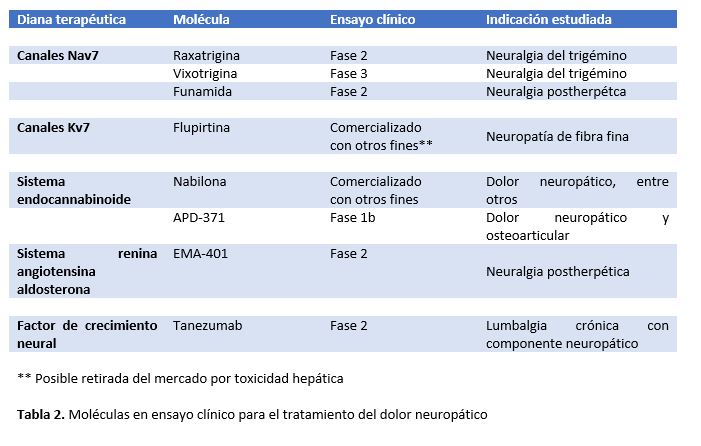

- Nuevas moléculas en ensayo clínico

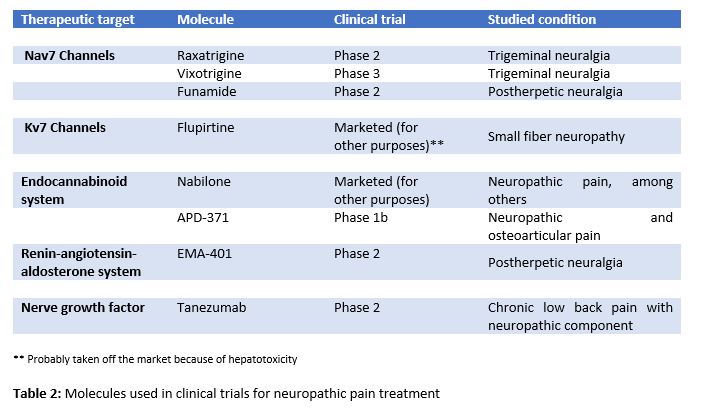

En los últimos años, se vienen desarrollando EC en humanos con principios activos dirigidos a distintas dianas moleculares propuestas para el tratamiento del DN (6,7). Algunos de los fármacos en desarrollo actúan principalmente sobre los canales iónicos voltaje-dependientes (Na+, K+), el sistema endocannabinoide, el sistema renina-angiotensina-aldosterona (SRAA) o sobre el receptor del factor de crecimiento neural (NGF) (Tabla 2).

- Canales iónicos voltaje-dependientes

- Canales Nav1.7 de Na

El canal Nav 1.7 es un canal de sodio voltaje-dependiente que se expresa de forma predominante en nociceptores de la raíz dorsal de la médula espinal. Participa en la fase ascendente del potencial de acción del nociceptor periférico, así como en la transmisión sináptica y liberación de neuropéptidos a nivel del asta dorsal medular (6). Raxatrigina (14), vixotrigina (15) y funamida (16) son inhibidores selectivos de Nav1.7 que se encuentran en EC en fase 2 (raxatrigina y funamida) y fase 3 (vixotrigina) para el tratamiento de DN en neuralgia del trigémino en el caso de raxatrigina y vigoxitrina; y neuralgia postherpética en el caso de funamida.

- Canales Kv7

Son canales de potasio voltaje-dependientes cuya inhibición está implicada en la patogenia de distintos trastornos que cursan con hiperexcitabilidad neuronal. Flupirtina es un activador de los canales Kv7 que recientemente ha demostrado efecto analgésico en el tratamiento del DN refractario debido a neuropatía de fibra fina. Sin embargo, se han descrito casos graves de toxicidad hepática (7). La principal subunidad de Kv7, Kv7.5 se expresa en las fibras C, y futuras moléculas con efecto activador selectivo de esta subunidad podrían ser estudiadas para el tratamiento del DN (6,7).

- Sistema endocannabinoide

El sistema endocannabinoide incluye dos receptores principales (CB1 y CB2), sus ligandos endógenos (anandamida y 2-araquidonoilglicerol) y una amplia maquinaria metabólica. La Nabilona, un cannabinoide sintético aprobado para el tratamiento de náuseas y vómitos secundarios a quimioterapia, ha mostrado eficacia en el tratamiento de varios tipos de dolor, incluido el neuropático (7,11). Otro agonista cannabinoide altamente selectivo para el receptor CB2, el APD371, ha obtenido resultados positivos en EC en fase Ib para el tratamiento del DN y osteoarticular (7). El desarrollo de agonistas selectivos de receptores cannabinoides es complejo debido a la alta implicación de los mismos en numerosos procesos fisiológicos. Algunos ligandos de CB2 se han relacionado con menor incidencia de efectos adversos a nivel del SNC.

- Sistema renina-angiotensina-aldosterona

La unión de angiotensina II (AT-II) a sus receptores, AT1 o AT2, ejerce un papel neuromodulador en el cerebro y la médula espinal. La AT-II participa en la regulación central y periférica de información sensorial, nocicepción, gusto y sistema visual. Además, la expresión de receptores AT1 y la conversión de AT-II a AT-III en neuronas del SNC están implicados en la modulación descendente del dolor (6,13). EMA401 es un antagonista selectivo del receptor AT2 que ha demostrado eficacia en el tratamiento del DN en pacientes con neuralgia postherpética en EC en fase II (17).

- Factor de crecimiento neuronal (NGF)

Implicado en la respuesta fisiológica dolorosa a estímulos nocivos, este factor de crecimiento se encuentra aumentado en gran variedad de cuadros de dolor agudo y crónico. Por este motivo se han desarrollado moléculas que actúan como antagonistas del NGF, con potenciales efectos analgésicos, destacando los anticuerpos dirigidos contra el receptor de NGF (6,13). Tanezumab, una IgG2 humanizada que bloquea la interacción de NGF con sus receptores TrkA y p75, ha demostrado mayor eficacia analgésica en pacientes con lumbalgia crónica con componente neuropático que naproxeno y placebo en EC en fase II (6).

- Nuevas dianas moleculares

En la actualidad se encuentran en desarrollo más de cien moléculas con potencial terapéutico en el tratamiento del DN. La mayor parte de estudios con ellas se han realizado en modelos animales. Aunque los resultados no son directamente extrapolables a humanos, muchos son esperanzadores (13,18). Algunas moléculas de especial interés son los receptores sigma, las efrinas y los receptores de estrés del retículo endoplasmático.

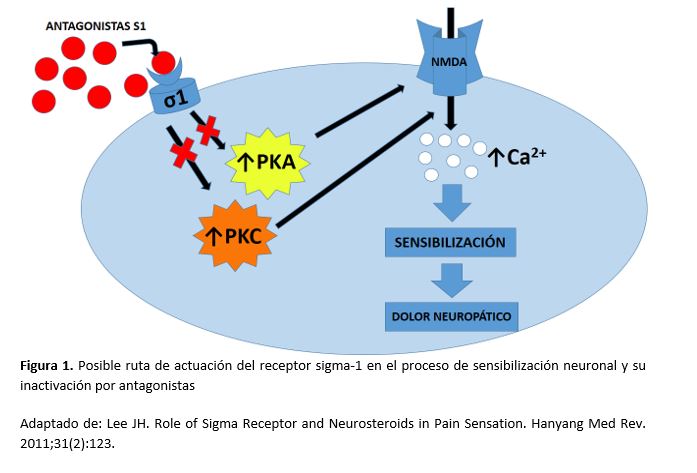

- Receptores sigma

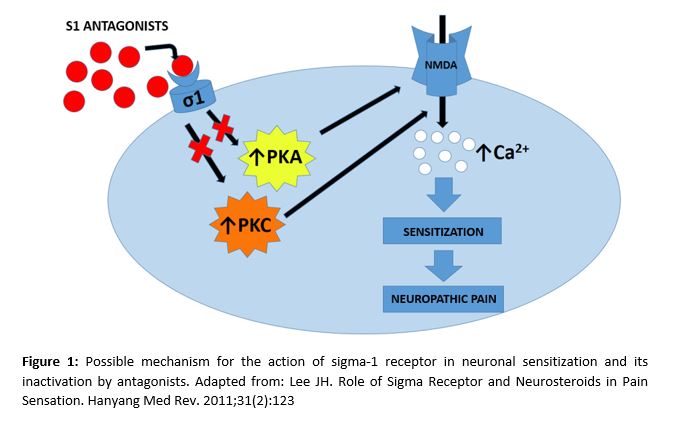

Se trata de proteínas de tipo chaperona que actúan acopladas a canales NMDA, provocando la entrada de calcio en la neurona. El receptor sigma-1 juega un papel esencial en el proceso de sensibilización neuronal y en la cronificación del dolor, motivo por el que su mecanismo de acción (Figura 1) está siendo ampliamente estudiado (19–21). Además, se ha demostrado que una lesión nerviosa aumenta el número de receptores sigma-1 en las neuronas dañadas (8). Algunos estudios con ratones a los que se ha inducido DN con paclitaxel muestran que tanto el bloqueo farmacológico con antagonistas de sigma-1, como la desactivación genética del mismo en ratones knockout inhiben el DN producido por paclitaxel (21).

- Efrinas

Son ligandos de receptores tirosin-kinasa, implicadas en el desarrollo neuronal. Presentan receptores en las láminas I y III del asta dorsal y en neuronas de los GRD (22). Modulan la actividad sináptica dependiente de NMDA y participan en la regulación del dolor a nivel medular. Las efrinas también intervienen en las vías descendentes del dolor, a través de la 3-fosfatidil-inositol-kinasa (23) y la proteín-kinasa C-γ (24), aumentando la excitabilidad de las neuronas nociceptivas y su plasticidad sináptica.

- Receptores de estrés del retículo endoplasmático (ERS)

Ante moléculas de estrés, se produce un incorrecto plegamiento proteico en el retículo endoplasmático (RE). Como mecanismo de defensa, se desencadena una repuesta a proteínas desplegadas (RPD) mediado por chaperonas. Esta respuesta del RE también es activada por los agentes proinflamatorios. Las proteínas de unión a la Inmunoglobulina (BIP) forman parte de la familia de las chaperonas y en estudios realizados en modelos murinos con dolor inflamatorio orofacial se produce un incremento de BIP (25), sugiriendo que la activación crónica del sistema RPD puede inducir vulnerabilidad neuronal en respuesta a los estímulos de DN.

- β-catenina, Wnt, Ryk

Son moléculas implicadas en el desarrollo y metabolismo neuronal. Se ha comprobado un aumento de Wnt3 en el asta dorsal en ratones a los que se ha ligado el nervio ciático. Un inhibidor de la señalización Wnt/b-catenina, XAV939, disminuye la sensibilización del DN (26). El bloqueo de Ryk en ratones suprime la hiperexcitabilidad neuronal y la neuroplasticidad en el asta dorsal. Otros estudios sugieren un potencial terapéutico al intervenir sobre estos receptores en el tratamiento del DN (18,27,28).

- D-aminoácido oxidasa (DAAO)

Es una enzima peroxisomal que cataliza la desaminación oxidativa de los D-aminoacidos. La administración intratecal de inhibidores de la DAAO en modelos murinos ha demostrado reducir el DN (29) y el dolor de la fase tónica inducida por formalina (30).

- Modificaciones epigenéticas

La modificación epigenética de genes relacionados con la expresión de receptores, canales iónicos y otros mediadores alterados en el DN podría ser una vía terapéutica. Varios estudios sugieren que se produce una alteración en la expresión de estos mediadores por metiltransferasas, desmetilasas, histona-acetil transferasas (HAC) e histona-deacetilasas (HDAC), habiéndose demostrado la influencia de HAC sobre la expresión de quimioquinas y de HDAC sobre la expresión de citoquinas en células gliales y macrófagos (31).

- Tratamiento no farmacológico del dolor neuropático

Existe una gran variedad de técnicas no farmacológicas que pueden complementar el abordaje terapéutico del DN, cumpliendo un papel importante en el bienestar psicológico del paciente y en el curso evolutivo del cuadro doloroso (9).

- Terapias no invasivas

Varios EC en humanos han estudiado la relación entre la actividad física y la sensibilidad al dolor. El ejercicio físico se asocia con una mayor tolerancia al dolor en cuadros de dolor lumbar crónico, fibromialgia, osteoartritis y DN periférico (32,33). En el DN también parecen ser beneficiosas la fisioterapia y técnicas como la terapia en espejo y la imaginería motora graduada (1,9). Por otro lado, la psicoterapia, especialmente la terapia cognitivo conductual, se ha empleado para promover una participación activa del paciente en su cuadro doloroso y reducir sus consecuencias a nivel afectivo, funcional y social, si bien no hay evidencia que respalde su eficacia en el DN (1).

- Terapias invasivas y mínimamente invasivas

Las técnicas invasivas en el tratamiento del dolor parecen ser una alternativa terapéutica válida en determinados pacientes con DN que no han respondido a otros tratamientos (1). Han ido cobrando fuerza en los últimos años y se prevé que continúen avanzando. Incluyen, entre otras, la radiofrecuencia (RF), la neuroestimulación y el bloqueo nervioso.

- Radiofrecuencia

La RF es una técnica mínimamente invasiva que genera campos electromagnéticos y térmicos, regulando la expresión de canales en el GRD y contribuyendo a la neuromodulación del sistema nervioso (34,35). La RF pulsada se utiliza en dolor articular y muscular, y ha demostrado ser eficaz en cuadros de dolor radicular y neuralgias (36).

- Neuroestimulación

Destacan la estimulación eléctrica medular (EEM) y la estimulación nerviosa transcutánea (TENS, por sus siglas en inglés). La EEM actúa en las columnas posteriores de la médula espinal y modula el estímulo transmitido por las fibras C a través de las fibras Aβ (1), aunque todavía se desconoce el mecanismo por el cual produce analgesia (9). Resulta eficaz en el síndrome de la espalda fallida y en el síndrome de dolor regional complejo, entre otros (37). Por otro lado, la TENS es una técnica no invasiva y ampliamente usada, que activa las vías descendentes inhibitorias, aunque no hay estudios que demuestren claramente su eficacia (38).

- Bloqueo nervioso

La terapia de bloqueo nervioso es una técnica extensamente utilizada en cuadros de dolor crónico y útil tanto para el diagnóstico como para el tratamiento del DN (39). Se ha publicado el caso de una paciente con dolor abdominal residual postoperatorio, refractario incluso a técnicas invasivas, que precisó de un bloqueo nervioso a ese nivel para confirmar el origen nervioso periférico del dolor y proporcionar analgesia mantenida mediante la inserción posterior de un catéter e infusión continua de anestésico local (40).

- Conclusiones

El tratamiento del DN es complejo e incluye abordajes farmacológicos y no farmacológicos. Dentro de los primeros, existen varios grupos. Entre los agentes de primera línea destacan los ADT, ISRN y anticonvulsivantes como la pregabalina o la gabapentina; en segunda línea se encuentran los opioides menores (tramadol) y la lidocaína o la capsaicina tópicas; en tercera línea destacan opioides mayores como la morfina; y en cuarta línea otros anticonvulsivantes y opioides mayores y la toxina botulínica, entre otros. Pese a la variedad de fármacos disponibles, la eficacia global es limitada en un número significativo de pacientes, por lo que es necesario diseñar nuevas moléculas más potentes.

Algunas de las moléculas más destacadas en EC en la actualidad intervienen sobre canales iónicos (Nav 1.7, Kv 7), el sistema endocannabinoide, el sistema RAA o el receptor del NGF. Además, otras moléculas están demostrando resultados de gran interés en modelos animales, destacando las que interactúan con los receptores sigma, los receptores de ERS, la tríada b-catenina/Wnt/Ryk, DAAO y varios reguladores epigenéticos. Por último, hay que reseñar que el tratamiento no farmacológico del dolor está cobrando un papel cada vez mayor, con distintas modalidades que incluyen terapias no invasivas (ejercicio físico, fisioterapia, imaginería motora graduada, psicoterapia) e invasivas y mínimamente invasivas (radiofrecuencia, neuroestimulación, bloqueo nervioso).

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, et al. Neuropathic Pain. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:1–45.

- Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008 Jun;136(3):380–7.

- Van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain [Internet]. 2014 Apr [cited 2019 Mar 24];155(4):654–62.

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb;14(2):162–73.

- Galvez R. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre el Tratamiento Farmacológico del Dolor Neuropático Periférico en Atención Primaria. 2016.

- Sałat K, Kowalczyk P, Gryzło B, Jakubowska A, Kulig K. New investigational drugs for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23(8):1093–104.

- Yan Y yi, Li C yuan, Zhou L, Ao L yao, Fang W rong, Li Y man. Research progress of mechanisms and drug therapy for neuropathic pain. Life Sci. 2017;190:68–77.

- Bangaru ML, Weihrauch D, Tang Q-B, Zoga V, Hogan Q, Wu H. Sigma-1 receptor expression in sensory neurons and the effect of painful peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain. 2013 Sep;9:47.

- Xu L, Zhang Y, Huang Y. Translational Research in Pain and Itch. Vol. 904. 2016. p. 117-130.

- Attal N. Pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: The latest recommendations. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175(1–2):46–50.

- Mu A, Weinberg E, Clarke H. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:844–52.

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice ASC. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: systematic review, meta-analysis and updated NeuPSIG recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2016;14(2):162–73.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N. Emerging therapies for neuropathic pain: new molecules or new indications for old treatments? Pain. 2018;159(3):576–82.

- Zheng Y, Wang W, Li Y, Yu Y, Gao Z. Enhancing inactivation rather than reducing activation of Nav1.7 channels by a clinically effective analgesic CNV1014802. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(4):587–96.

- Di Stefano G, Truini A, Cruccu G. Current and Innovative Pharmacological Options to Treat Typical and Atypical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Drugs. 2018;78(14):1433–42.

- Price N, Namdari R, Neville J, Proctor KJW, Kaber S, Vest J, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Topical Sodium Channel Inhibitor (TV-45070) in Patients With Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN). Clin J Pain. 2017 Apr;33(4):310–8.

- Rice ASC, Dworkin RH, McCarthy TD, Anand P, Bountra C, McCloud PI, et al. EMA401, an orally administered highly selective angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist, as a novel treatment for postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet (London, England). 2014 May;383(9929):1637–47.

- Khangura RK, Sharma J, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. An integrated review on new targets in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019 Jan;23(1):1–20.

- Merlos M, Romero L, Zamanillo D, Plata-Salamán C, Vela JM. Sigma-1 Receptor and Pain. In: Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2017. p. 131–61.

- Lee J-H. Role of Sigma Receptor and Neurosteroids in Pain Sensation. Hanyang Med Rev. 2011 ;31(2):123.

- Nieto FR, Cendán CM, Sánchez-Fernández C, Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Tejada MA, et al. Role of Sigma-1 Receptors in Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain in Mice. J Pain. 2012 Nov;13(11):1107–21.

- Bundesen LQ, Scheel TA, Bregman BS, Kromer LF. Ephrin-B2 and EphB2 regulation of astrocyte-meningeal fibroblast interactions in response to spinal cord lesions in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2003 Aug;23(21):7789–800.

- Yu L-N, Zhou X-L, Yu J, Huang H, Jiang L-S, Zhang F-J, et al. PI3K Contributed to Modulation of Spinal Nociceptive Information Related to ephrinBs/EphBs. Baccei ML, editor. PLoS One. 2012 Aug;7(8):e40930.

- Zhou X-L, Zhang C-J, Wang Y, Wang M, Sun L-H, Yu L-N, et al. EphrinB–EphB signaling regulates spinal pain processing via PKCγ. Neuroscience. 2015 Oct;307:64–72.

- Yang F, Whang J, Derry WT, Vardeh D, Scholz J. Analgesic treatment with pregabalin does not prevent persistent pain after peripheral nerve injury in the rat. Pain. 2014 Feb;155(2):356–66.

- Itokazu T, Hayano Y, Takahashi R, Yamashita T. Involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the development of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Res. 2014 Feb;79:34–40.

- Yang QO, Yang W-J, Li J, Liu F-T, Yuan H, Ou Yang Y-P. Ryk receptors on unmyelinated nerve fibers mediate excitatory synaptic transmission and CCL2 release during neuropathic pain induced by peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain. 2017 Jan 31;13:174480691770937.

- Gao K, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Wan Z, Yao T, Li H, et al. Neuroprotective effect of rapamycin on spinal cord injury via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Neural Regen Res. 2015 Jun;10(6):951.

- Zhao J, Yuan G, Cendan CM, Nassar MA, Lagerström MC, Kullander K, et al. Nociceptor-Expressed Ephrin-B2 Regulates Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain. Mol Pain. 2010 Jan 29 ;6:1744-8069-6–77.

- Chen X-L, Li X-Y, Qian S-B, Wang Y-C, Zhang P-Z, Zhou X-J, et al. Down-regulation of spinal d-amino acid oxidase expression blocks formalin-induced tonic pain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 May 11;421(3):501–7.

- Penas C, Navarro X. Epigenetic Modifications Associated to Neuroinflammation and Neuropathic Pain After Neural Trauma. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018 Jun 7;12:158.

- Dobson JL, McMillan J, Li L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014 Apr 4;8:102.

- Kroll HR. Exercise Therapy for Chronic Pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):263–81.

- Liu Y, Feng Y, Zhang T. Pulsed Radiofrequency Treatment Enhances Dorsal Root Ganglion Expression of Hyperpolarization-Activated Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channels in a Rat Model of Neuropathic Pain. J Mol Neurosci. 2015 Sep 28;57(1):97–105.

- Abejón D, Parodi E, Blanco T, Cavero V, Pérez-Cajaraville J. Radiofrecuencia pulsada del ganglio dorsal de las raíces lumbares. Rev la Soc Española del Dolor. 2011;18(2):135–40.

- Chang MC. Efficacy of Pulsed Radiofrequency Stimulation in Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain Physician. 2018;21(3):E225–34.

- Wong SSC, Chan CW, Cheung CW. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic non-cancer pain: A review of current evidence and practice. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23(5):517–23.

- Vance CGT, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Using TENS for pain control: the state of the evidence. Pain Manag. 2014 May;4(3):197–209.

- Wijayasinghe N, Andersen KG, Kehlet H. Neural Blockade for Persistent Pain After Breast Cancer Surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(4):272–8.

- Guirguis MN, Abd-Elsayed AA, Girgis G, Soliman LM. Ultrasound-Guided Transversus Abdominis Plane Catheter for Chronic Abdominal Pain. Pain Pract. 2013 Mar;13(3):235–8.

An Updated Review of Neuropathic Pain Treatment: State of Art and Future Prospects

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a difficult-to-manage kind of pain that affects 10% of the population. Nowadays, there are some agents that can be used for its treatment, and they are grouped according to different lines. However, their pharmacological effectiveness is only proved on a reduced number of patients. For this reason, new therapeutic strategies need to be developed. Certain molecules currently are on the initial stages of human clinical trials, and many of them are showing encouraging results. Furthermore, there is an increasingly accurate knowledge about the different molecular pathways related to NP. This advance is promoting the development of new molecules with potential therapeutic targets. Some of these agents are being tested with animal models, and they are showing a significant analgesic potency. Finally, non-pharmacological treatment in NP is becoming more important in clinical practice through alternatives such as radio frequency, stimulation, and nerve block therapy. The aim of this work is to review the state of art of NP treatment. For that purpose, the agents approved until today and their main action mechanisms should be considered, with a special emphasis on some of the latest molecules used on human clinical

trials and those which are in development with animal models. Moreover, some of the main non-pharmacological strategies used to manage pain nowadays are also reviewed.

Keywords: neuropathic pain, new agents, pharmacological treatment, non-pharmacological treatment, clinical trial.

- Introduction

Neuropathic Pain (NP) is caused by a disease or a direct injury of the central or peripheral nervous system, and it comprises a wide range of etiological causes (1, 2). Although there are some difficulties to determine the prevalence of NP, it is estimated that 7-10% of the population suffer from it. Accordingly, women and people aged over 50 are the most common population groups affected by NP (2). Normally, the most frequently affected areas are the hind neck, the lumbar region, and lower and higher extremities (3). Among the different pathologies that are commonly related to this kind of pain, it is important to highlight peripheral neuropathies, post-herpetic neuralgia, traumatic nerve injury, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, and various types of cancer (3).

NP is considered by many experts as one of the painful syndromes that are most difficult to manage (2). The treatment complexity of this syndrome has led to the development of multiple clinical trials, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines such as those of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (4). According to the scientific evidence and these guidelines, the pharmacological treatment of NP usually follows different lines, each of them with its own pharmacological group (5). However, in a significant number of patients, the relief obtained is quite limited after applying all of the pharmacological lines.

Currently, there are some agents for NP treatment on their first stages of clinical trials that are achieving promising results (6, 7). On the other hand, several potential therapeutic targets have been proposed based on a better understanding of NP physiopathology and on the results achieved with animal models (8). Finally, it is important to bear in mind that NP treatment and management include non-pharmacological measures, and that there are some therapies, such as stimulation and nerve blocks, that are increasingly becoming relevant (9).

This article aims at reviewing the state of art regarding NP pharmacological treatment by examining the latest international clinical guidelines, the treatments with better results in later stage clinical trials, and the experimental development of agents in animal models. Furthermore, some of the potential therapeutic targets that have recently been proposed are also reviewed.

- Neuropathic pain pharmacological treatment

With regard to the NP pharmacological treatment, several treatment lines have demonstrated their efficacy, highlighting anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

- First-line agents

TCAs (e.g. amitriptyline) belong to this group. They inhibit serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, which increases the top-down inhibitory control of pain (10). However, they also act on the sodium channel, beta-2 adrenergic receptors, and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, thus producing side effects such as sedation, dizziness, dry mouth, and orthostatic hypotension (5). Furthermore, SNRIs (e.g. duloxetine and venlafaxine) are also considered first-line agents, and have had positive results in many cases, being nausea their most common side effect (11). Finally, anticonvulsants (e.g. pregabalin and gabapentin) have also demonstrated their efficacy in NP pharmacological treatment. They reduce the calcium entry in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, decreasing the central sensitization (10). As they often cause drowsiness, dizziness, and edemas, it is recommended to start the treatment at low doses (5, 11).

- Second-line agents

Tramadol can be mentioned among the second-line agents. It is a weak opioid which acts as a weak mu receptor agonist, and as an SNRI. It is recommended to use Tramadol with caution due to the dependence and abuse risks, and also due to its side effects, including nausea, confusion, drowsiness and the reduction of seizure thresholds (5, 11, 12).

Other second-line treatments, especially recommended for peripheral NP, are topical agents like lidocaine and capsaicin. 5% lidocaine transdermal patches block the sodium channel and decrease nerve depolarization. 0.075% capsaicin cream and 8% capsaicin patches cause the desensitization of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, and they modulate pain signaling (1, 5).

- Third-line agents

Strong opioids (e.g. oxycodone and morphine) have recently been promoted to third-line agents, as opposed to their prior consideration as first or second-line treatment (12). This is primarily due to their potential side effects, risks and the need for them to be monitored in NP treatment. These opioids are more likely than tramadol to cause withdrawal, dependence, and abuse. Moreover, opioids can induce nausea, constipation, drowsiness, respiratory depression; and, eventually, hyperalgesia, and endocrine disruptions (5, 11).

- Fourth-line agents

Although some agents are probably effective in certain subgroups of patients, the current recommendations for the use of all other drug treatments for NP are weak or inconclusive (1). Recommended fourth-line treatments include other anticonvulsants (e.g. oxcarbazepine, topiramate), other strong opioids (tapentadol), and botulinum toxin, among others (11, 12).

Despite the availability of a large number of therapies, drugs largely used to relieve NP usually have a limited efficacy or dose-limiting side effects (Table 1). Therefore, the validation of novel agents and the study of potential therapeutic targets is becoming increasingly necessary (13).

- New molecules in clinical trials

In the last few years, some clinical trials with active principles, which were targeted to different molecules to relieve NP, have been conducted in humans (6, 7). Some of the drugs currently under development are focused on voltage-gated ion channels (Na+, K+), on the endocannabinoid system, on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) or on the nerve growth factor (NGF) receptor (Table 2).

- Voltage-gated ion channels

- 7 sodium channels

Nav1.7 is the voltage-gated sodium channel that predominantly expresses in nociceptors in the dorsal root of the spinal cord. It contributes to the initiation and the upstroke phase of the peripheral nociceptor action potential, as well as to synaptic transmission and to neuropeptide release in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (6). Raxatrigine (14), vixotrigine (15), and funamide (16) are highly selective inhibitors of Nav1.7 in phase 2 trial (raxatrigine, funamide) and phase 3 trial (vixotrigine) to treat NP in trigeminal neuralgia in the case of raxatrigine and vixotrigine, and postherpetic neuralgia in the case of funamide.

- Kv7 potassium channels

Kv7 is a voltage-gated non-inactivating potassium channel, and its down-regulation has been implicated in several hyperexcitability-related disorders. Flupirtine, a Kv7 channel activator, has recently showed analgesic effects on refractory NP treatment due to small fiber neuropathy. However, hepatotoxicity has been reported with flupirtine (7). Kv7.5, the main Kv7 subunit which is expressed by C-fibers, focuses on the possible role of selective Kv7.5 enhancers in NP treatment (6, 7).

- Endocannabinoid system

The endocannabinoid system includes two receptors (CB1 and CB2), their endogenously produced ligands (anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol), and a wide metabolic machinery. Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid approved for nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, has showed efficacy in the treatment of different types of pain, including NP (7, 11). Notably, APD371, a highly selective agonist of the CB2, has obtained positive results in a phase Ib clinical trial in NP and osteoarthritic treatment (7). However, the development of selective agonists of the cannabinoid receptors is complex because they are involved in diverse physiological processes. Some CB2 ligands produce no major side effects at the central nervous system.

- Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

The union of angiotensin II (Ang II) to its receptors, AT1 and AT2, acts as a neuromodulator in the brain and in the spinal cord. Ang II participates in the central and peripheral regulation of sensory nervous information, nociception, and taste and visual system. Furthermore, the expression of AT1 receptors and the conversion of Ang II to Ang III in central nervous system neurons are involved in a descending pain modulation (6, 13). EMA401 is a selective antagonist of AT2 receptors that has proved to be an effective option in NP treatment in patients with postherpetic neuralgia in phase II of clinical trials (17).

- Nerve growth factor

This growth factor is involved in the painful physiological response to harmful stimuli, and it is increased in a great variety of cases of acute and chronic pain. For this reason, molecules that act as NGF antagonists have been developed (6,13). Tanezumab, a humanized IgG2 that blocks the interaction between NGF and its TrkA and p75 receptors, has demonstrated a better analgesic efficacy in patients with neuropathic component in chronic back low pain than naproxen and placebo in phase II clinical trials (6).

- New molecular targets

Nowadays, over one hundred molecules with a therapeutic potential in NP treatment are being developed. Most of the studies have been conducted on animals. Although many results are positive, they are not directly applicable to humans (13, 18). Some molecules of special interest are sigma receptors, ephrins, and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) receptors.

- Sigma receptors

Sigma receptors are chaperon-like proteins that act in combination with NMDA channels and enable calcium influx in neurons. The sigma-1 receptor plays an essential role in neuronal sensitization and in chronic pain development. This is why its action mechanism (Figure 1) is being thoroughly studied (19-21). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that nerve injuries increase the number of sigma-1 receptors in the damaged neurons (8). Some studies conducted on NP-induced mice with paclitaxel show that both pharmacological blockade with sigma-1 antagonists, as well as the genetic deactivation of it in knockout mice, inhibit the NP caused by paclitaxel (21).

- Ephrins

Ephrins are receptor tyrosine kinase ligands involved in neural development. They present receptors in the laminae I-III of the dorsal horn and in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (22). In addition, they regulate the NMDA-dependent synaptic activity and they participate in spinal pain processing. Ephrins participate as well in upstream pain mechanisms through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (23) and protein kinase C-γ (24), increasing the excitability of nociceptive neurons and their synaptic plasticity.

4.3 Endoplasmic reticulum stress receptors

In the presence of stress molecules, an incorrect protein folding occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). As a defense mechanism, the unfolded protein response (UPR) mediated by chaperones is triggered. This ER response can also be activated by pro-inflammatory agents. Binding immunoglobulin proteins (BiP) belong to the chaperone family. Studies conducted in murine models with orofacial inflammatory pain showed an increase in BiP (25), suggesting that chronic activation of the UPR system may induce neuronal vulnerability in response to NP stimuli.

4.4 β-catenin, Wnt, Ryk

They are molecules involved in neuronal metabolism and development. It has been observed an increase of Wnt3 in the dorsal horn of rats whose sciatic nerve had been ligated. A Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor, XAV939, attenuated NP sensitivity (26). Blocking Ryk in mice suppresses neuronal hyperexcitability and neuroplasticity in the dorsal horn. Other studies suggest that intervening on these receptors may have a therapeutic potential in NP treatment (18, 27, 28).

4.5 D-amino acid oxidase

It is a peroxisomal enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of D-amino acids. Intrathecal administration of D-amino acids oxidase (DAAO) inhibitors in murine models revealed NP reduction (29) and formalin-induced tonic phase pain (30).

4.6 Epigenetic modifications

The epigenetic modification of genes related to the expression of receptors, ion channels and other mediators altered in NP could be a therapeutic way. Several studies suggest that there is an alteration in the expression of these mediators by methyltransferases, demethylases, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). In this line, the influence of HATs on the expression of chemokines and that of HDACs on the expression of cytokines in glial cells and macrophages have been demonstrated (31).

- Neuropathic pain non-pharmacological treatment

There is a great variety of non-pharmacological techniques that may complement NP treatment by playing an important role in the psychological well-being of the patient, as well as in the evolutionary course of pain (9).

5.1. Non-invasive therapies

Several clinical trials in humans have studied the relationship between physical activity and pain sensitivity. Physical exercise is associated with a greater tolerance to pain in chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and peripheral NP (32, 33). Physiotherapy and techniques such as mirror therapy and graded motor imagery also appear to be beneficial in NP (1, 9). On the other hand, psychotherapy, especially cognitive-behavioral therapy, has been used to promote the patient’s active participation in their painful condition and to reduce its consequences at affective, functional and social levels, although there is no evidence to prove its efficacy in NP (1).

5.2. Invasive and minimally invasive therapies

The invasive techniques used in pain treatment seem to be a valid therapeutic alternative for those patients with NP for whom other treatments have not been effective (1). The importance of these techniques has grown in the last few years, and it is expected to keep growing. They include radio frequency (RF), neurostimulation, and nerve block therapy, among others.

5.2.1. Radio frequency

RF is a minimally invasive technique that produces electromagnetic and thermal fields in order to regulate the channel expressions in DRG. It also contributes to the neuromodulation of the nervous system (34, 35). Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) is used to treat joint and muscle pain, and it has been proved to be effective in cases of radicular pain and neuralgia (36).

5.2.2. Neurostimulation

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) are two remarkable techniques used in neurostimulation. On the one hand, SCS acts at the back of the spinal cord and modulates the stimuli transmitted by the C-fibers through Aβ-fibers (1). However, it is still unknown how this produces analgesia (9). SCS is effective in the treatment of syndromes like failed back surgery syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome, among others (37). On the other hand, TENS is a widely used non-invasive technique that activates the descending inhibitory systems, although its efficacy has not been proved by any research yet (38).

5.2.3. Nerve block therapy

Nerve block therapy is a widely used procedure for chronic pain conditions. It is useful for both NP diagnosis and treatment (39). Guirguis et al. (40) reported the case of a patient with postoperative residual abdominal pain, which was refractory to invasive techniques. To determine the origin of the pain, it was necessary to perform a nerve block in the area where the patient had the pain. Then, the peripheral source of the abdominal pain was confirmed and, by inserting a catheter which continuously infused a local anesthetic, the analgesic effect was maintained.

- Conclusions

NP treatment is a complex task that can be approached by both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods. There are several groups inside the pharmacological ones. First-line agents include TCA, SNRI and anticonvulsive agents such as pregabalin and gabapentin. Second-line agents include weak opioids (tramadol) and topical lidocaine or capsaicin. Among third-line agents, strong opioids like morphine stand out. Finally, fourth-line agents are represented by the use of strong opioids, botulinum toxin, and other anticonvulsive agents. Although there is a wide variety of agents available, their overall efficacy is limited just to certain patients. Therefore, more powerful molecules should be designed.

Nowadays, some of the most important molecules in clinical trials act on ion channels (Nav 1.7, Kv 7), on the endocannabinoid system, on the RAAS or on NGF receptors. Moreover, some other molecules are showing interesting results in animal models. The most relevant ones are those which interact with sigma receptors, ERS receptors, the β-catenin/Wnt/Ryk triad, DAAO, and several epigenetic regulators. To conclude, non-pharmacological pain treatment is becoming increasingly important. This kind of treatment can be applied by using non-invasive therapies (physical activity, physiotherapy, graded motor imagery, psychotherapy), and invasive or minimally invasive therapies (RF, neurostimulation, and nerve block therapy).

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, et al. Neuropathic Pain. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:1–45.

- Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008 Jun;136(3):380–7.

- Van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain [Internet]. 2014 Apr [cited 2019 Mar 24];155(4):654–62.

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb;14(2):162–73.

- Galvez R. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre el Tratamiento Farmacológico del Dolor Neuropático Periférico en Atención Primaria. 2016.

- Sałat K, Kowalczyk P, Gryzło B, Jakubowska A, Kulig K. New investigational drugs for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23(8):1093–104.

- Yan Y yi, Li C yuan, Zhou L, Ao L yao, Fang W rong, Li Y man. Research progress of mechanisms and drug therapy for neuropathic pain. Life Sci. 2017;190:68–77.

- Bangaru ML, Weihrauch D, Tang Q-B, Zoga V, Hogan Q, Wu H. Sigma-1 receptor expression in sensory neurons and the effect of painful peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain. 2013 Sep;9:47.

- Xu L, Zhang Y, Huang Y. Translational Research in Pain and Itch. Vol. 904. 2016. p. 117-130.

- Attal N. Pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: The latest recommendations. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175(1–2):46–50.

- Mu A, Weinberg E, Clarke H. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:844–52.

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice ASC. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: systematic review, meta-analysis and updated NeuPSIG recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2016;14(2):162–73.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N. Emerging therapies for neuropathic pain: new molecules or new indications for old treatments? Pain. 2018;159(3):576–82.

- Zheng Y, Wang W, Li Y, Yu Y, Gao Z. Enhancing inactivation rather than reducing activation of Nav1.7 channels by a clinically effective analgesic CNV1014802. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(4):587–96.

- Di Stefano G, Truini A, Cruccu G. Current and Innovative Pharmacological Options to Treat Typical and Atypical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Drugs. 2018;78(14):1433–42.

- Price N, Namdari R, Neville J, Proctor KJW, Kaber S, Vest J, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Topical Sodium Channel Inhibitor (TV-45070) in Patients With Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN). Clin J Pain. 2017 Apr;33(4):310–8.

- Rice ASC, Dworkin RH, McCarthy TD, Anand P, Bountra C, McCloud PI, et al. EMA401, an orally administered highly selective angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist, as a novel treatment for postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet (London, England). 2014 May;383(9929):1637–47.

- Khangura RK, Sharma J, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. An integrated review on new targets in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019 Jan;23(1):1–20.

- Merlos M, Romero L, Zamanillo D, Plata-Salamán C, Vela JM. Sigma-1 Receptor and Pain. In: Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2017. p. 131–61.

- Lee J-H. Role of Sigma Receptor and Neurosteroids in Pain Sensation. Hanyang Med Rev. 2011 ;31(2):123.

- Nieto FR, Cendán CM, Sánchez-Fernández C, Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Tejada MA, et al. Role of Sigma-1 Receptors in Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain in Mice. J Pain. 2012 Nov;13(11):1107–21.

- Bundesen LQ, Scheel TA, Bregman BS, Kromer LF. Ephrin-B2 and EphB2 regulation of astrocyte-meningeal fibroblast interactions in response to spinal cord lesions in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2003 Aug;23(21):7789–800.

- Yu L-N, Zhou X-L, Yu J, Huang H, Jiang L-S, Zhang F-J, et al. PI3K Contributed to Modulation of Spinal Nociceptive Information Related to ephrinBs/EphBs. Baccei ML, editor. PLoS One. 2012 Aug;7(8):e40930.

- Zhou X-L, Zhang C-J, Wang Y, Wang M, Sun L-H, Yu L-N, et al. EphrinB–EphB signaling regulates spinal pain processing via PKCγ. Neuroscience. 2015 Oct;307:64–72.

- Yang F, Whang J, Derry WT, Vardeh D, Scholz J. Analgesic treatment with pregabalin does not prevent persistent pain after peripheral nerve injury in the rat. Pain. 2014 Feb;155(2):356–66.

- Itokazu T, Hayano Y, Takahashi R, Yamashita T. Involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the development of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Res. 2014 Feb;79:34–40.

- Yang QO, Yang W-J, Li J, Liu F-T, Yuan H, Ou Yang Y-P. Ryk receptors on unmyelinated nerve fibers mediate excitatory synaptic transmission and CCL2 release during neuropathic pain induced by peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain. 2017 Jan 31;13:174480691770937.

- Gao K, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Wan Z, Yao T, Li H, et al. Neuroprotective effect of rapamycin on spinal cord injury via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Neural Regen Res. 2015 Jun;10(6):951.

- Zhao J, Yuan G, Cendan CM, Nassar MA, Lagerström MC, Kullander K, et al. Nociceptor-Expressed Ephrin-B2 Regulates Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain. Mol Pain. 2010 Jan 29 ;6:1744-8069-6–77.

- Chen X-L, Li X-Y, Qian S-B, Wang Y-C, Zhang P-Z, Zhou X-J, et al. Down-regulation of spinal d-amino acid oxidase expression blocks formalin-induced tonic pain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 May 11;421(3):501–7.

- Penas C, Navarro X. Epigenetic Modifications Associated to Neuroinflammation and Neuropathic Pain After Neural Trauma. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018 Jun 7;12:158.

- Dobson JL, McMillan J, Li L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014 Apr 4;8:102.

- Kroll HR. Exercise Therapy for Chronic Pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):263–81.

- Liu Y, Feng Y, Zhang T. Pulsed Radiofrequency Treatment Enhances Dorsal Root Ganglion Expression of Hyperpolarization-Activated Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channels in a Rat Model of Neuropathic Pain. J Mol Neurosci. 2015 Sep 28;57(1):97–105.

- Abejón D, Parodi E, Blanco T, Cavero V, Pérez-Cajaraville J. Radiofrecuencia pulsada del ganglio dorsal de las raíces lumbares. Rev la Soc Española del Dolor. 2011;18(2):135–40.

- Chang MC. Efficacy of Pulsed Radiofrequency Stimulation in Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain Physician. 2018;21(3):E225–34.

- Wong SSC, Chan CW, Cheung CW. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic non-cancer pain: A review of current evidence and practice. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23(5):517–23.

- Vance CGT, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Using TENS for pain control: the state of the evidence. Pain Manag. 2014 May;4(3):197–209.

- Wijayasinghe N, Andersen KG, Kehlet H. Neural Blockade for Persistent Pain After Breast Cancer Surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(4):272–8.

- Guirguis MN, Abd-Elsayed AA, Girgis G, Soliman LM. Ultrasound-Guided Transversus Abdominis Plane Catheter for Chronic Abdominal Pain. Pain Pract. 2013 Mar;13(3):235–8.

AMU 2019. Volumen 1, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

15/04/2019 22/04/2019 31/05/2019

Cita el artículo: Gálvez-López R, Rodríguez-Camacho M, Soriano-Mateos A, Querol-Carranza E. Presente y futuro en el tratamiento del dolor neuropático: una revisión actualizada. AMU. 2019; 1(1): 76-101