Cynthia Campos-Moreno ¹ , Manuel González-Díez ¹ , Clara Isabel Murillo-Hermosilla ¹ , Cristina Perea-García ¹ , Amanda Sánchez-Arés¹

1 Estudiante del Máster en Neurociencias Básicas Aplicadas y Dolor de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

TRANSLATED BY:

Beatriz Pérez-Cortés ² , Amy McCullough ² , Beatriz Moreno-Cuadrado ² , Lourdes Ureña-Pérez ² , Marta Giménez-Polo ² , Ígor Iribar-Revuelta ²

2 Student of the BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (UGR)

Resumen

Esta revisión pretende unificar los datos más relevantes conocidos en relación al mindfulness y sus aplicaciones en sujetos con dolor crónico. Para ello, se ha llevado a cabo una búsqueda bibliográfica sobre qué áreas del cerebro de pacientes con dolor crónico se activan ante este, y si su activación se ve modificada con la aplicación del mindfulness,su utilidad terapéutica por sí sola y en comparación con otras no farmacológicas, así como sus distintos efectos en distintos grupos de edad. A pesar de las aparentes contradicciones de sus mecanismos de actuación, parece tener una utilidad como terapia coadyuvante igual a otras terapias no farmacológicas, independientemente del grupo de edad, por lo que podría ser útil para prevenir el abuso o reducir la dependencia de los analgésicos.

Palabras clave: dolor crónico, mindfulness, neuroimagen, regulación del dolor, terapias alternativas, dolor pediátrico, dolor geriátrico.

Keywords: chronic pain, mindfulness, neuroimaging, pain management, alternative therapies, pediatric pain, geriatric pain.

- Introducción

Consideramos dolor crónico a aquel dolor que dura más de 3 meses o más del tiempo normal de cicatrización del tejido (1). Puede empeorar progresivamente y aparecer de manera intermitente, disminuyendo la calidad de vida del paciente. Es padecido por entre el 5.,5-33% de la población mundial adulta, aunque no es exclusivo de estos, ya que también puede aparecer en adolescentes y niños. El número de personas afectadas ha ido aumentando a lo largo de los años debido al envejecimiento de la población (2). Esto acarrea costes económicos, tanto para los sistemas de salud como para el trabajo de los pacientes, ya que puede conducir a una disminución de la productividad (1) o incluso al absentismo laboral (3), pudiendo suponer así pérdidas a la empresa u organización para la que se trabaje.

Durante las últimas dos décadas, uno de los tratamientos empleados para el dolor crónico ha consistido en la administración de opiáceos (4), ya que son muy buenos analgésicos. Sin embargo, debido a un crecimiento exponencial en la prescripción de estos fármacos, se ha producido un aumento en la tasa de muertes por sobredosis (2) y en la probabilidad de adicción. Así, se está buscando emplear tratamientos combinados, tanto farmacológicos como no farmacológicos, para reducir el uso de opioides (4). Entre los tratamientos no farmacológicos encontramos algunas terapias alternativas, las cuales han probado ser, la mayoría, efectivas frente al dolor crónico además de ser baratas, reduciéndose así los costes económicos. Entre ellas podemos mencionar las intervenciones basadas en el mindfulness, la terapia cognitivo-conductual, la terapia de aceptación y compromiso, la acupuntura y la hipnosis (4). Todas ellas pueden reducir la percepción del dolor e incrementar la funcionalidad. Además, otros tipos de terapias como la terapia ocupacional, la terapia física y el ejercicio también han resultado efectivas (2). En este artículo nos centraremos en las intervenciones basadas en el mindfulness.

Las intervenciones basadas en el mindfulness (IBM), como el yoga, la meditación o la reducción del estrés, consisten en la concienciación de no juzgar el momento presente (2), sino centrarse en él y aceptarlo (1), lo que permite a los pacientes enfrentar mejor la experiencia dolorosa (3). En definitiva, el objetivo es disminuir la percepción del dolor y mejorar la calidad de vida; y aunque a menudo no es posible eliminar el dolor, el paciente aprende técnicas para mejorar la productividad incluso en presencia de molestias (2).

No obstante, a pesar del papel prometedor del mindfulness, existen limitaciones debido al bajo número de estudios realizados, a la variabilidad de población y la variabilidad de técnicas que pueden emplearse (3), y a la baja calidad de los estudios realizados (5), lo que dificulta la estandarización y generalización de estos.

Incluso con estas limitaciones, también encontramos ventajas, como la mejoría de síntomas, la inexistente posibilidad de abuso, y la mejoría de condiciones comórbidas, como ansiedad o depresión (2,3). Con este artículo, mediante la recopilación de diferentes estudios, pretendemos mostrar tratamientos alternativos para sujetos con dolor crónico en los que no estén implicadas sustancias que puedan provocar adicción. Concretamente, vamos a centrarnos en la aplicación del mindfulness y en si este es, realmente, un tratamiento eficaz.

- Neurofisiología y neuroimagen:

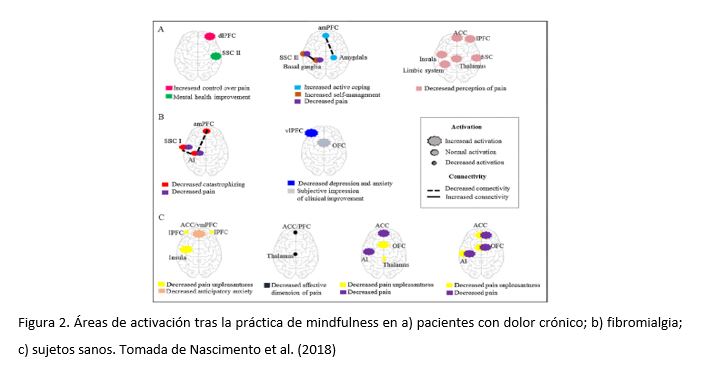

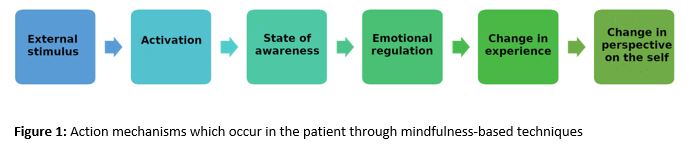

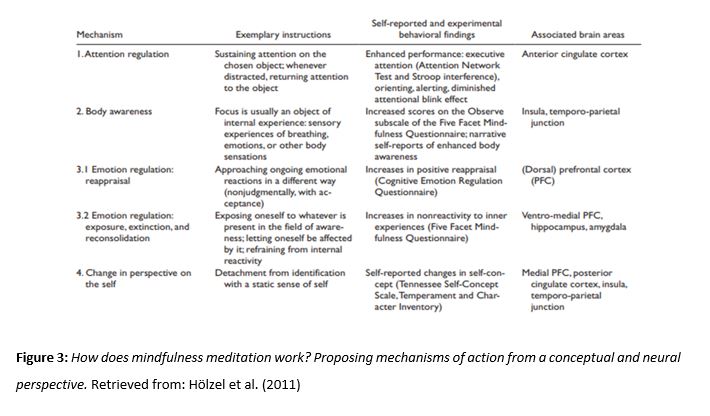

Las aplicaciones del mindfulness están bien establecidas. Sin embargo, los mecanismos de actuación aún resultan poco claros. Para explicar cómo actúan estas terapias (Imagen 1) se han propuesto cuatro componentes interrelacionados entre sí (Figura 3): regulación de la atención, conciencia corporal, regulación de la emoción y cambio de perspectiva sobre el yo (6), de los cuales abordaremos en profundidad solo los tres primeros. Para que el lector comprenda cómo estos se relacionan entre estos aspectos y el dolor, más adelante se comentará en profundidad cuáles son los elementos que conforman el dolor, cómo están estos representados en el cerebro, y cómo el mindfulness afecta a las áreas implicadas en ellos. Al final de este trabajo se adjunta un glosario con especificaciones de las siglas usadas en este apartado.

Los componentes de actuación del mindfulness y el dolor se explican de la siguiente manera:

- Regulación de la atención:

Se define como el proceso de centrar la atención en un objeto, reconocer las distracciones y luego devolver el enfoque al objeto. Diversos estudios (7,8) sugieren una mayor activación de la corteza cingulada anterior (CCA) y corteza prefrontal medial dorsal (CPFmd), ambas áreas implicadas en el proceso de regulación de la atención.

- Conciencia corporal:

La conciencia corporal se refiere al proceso de centrarse en una estructura o tarea dentro del cuerpo.

Existen dos posibles mecanismos que implican ínsula anterior derecha (IAd), en la que se encuentra una mayor concentración de materia gris, por un lado, y por acción de la CCA y la corteza prefrontal dorsolateral (CPFdl) sobre la amígdala por otro. Sin embargo, estudios a corto plazo sugieren que estos cambios comienzan en la región temporoparietal, y no en la ínsula (6,9).

- Regulación emocional:

Se da bien a nivel cognitivo (atención plena) controlando cuando se presta atención o se cambia la

respuesta a un estímulo, lo cual se consigue a través de una reevaluación (interpretando el estímulo de una manera más positiva) o extinción (revertir la respuesta al estímulo) de este; o bien a nivel conductual, inhibiendo la expresión de ciertos comportamientos en respuesta a un estímulo (6).

Se han sugerido dos sistemas, que implicarían la CPF lateral (CPFl), que maneja la atención selectiva, y la CPF ventral (CPFv) que participa en la inhibición de una respuesta por un lado y la CCA, por otro. (6,10)

- Dolor:

Según Bilevicius et al. (11), el dolor está compuesto de tres factores: sensorial, activando las cortezas somatosensoriales primaria y secundaria (CSS I y II) y del tálamo (TA); cognitivo, que activa la CPF; y afectivo-motivacional, el cual aumenta la actividad en la CCA y en las partes posterior y anterior de la ínsula (IP e IA). El mindfulness actúa directa o indirectamente en muchas de ellas, como se ha visto anteriormente.

Un estudio por Grant et al. (12) reveló que meditadores experimentados mostraron una mayor activación de la ínsula, el TA y el córtex medio-cingulado, y una menor activación de las regiones responsables del control de la emoción (CPF medial, corteza orbitofrontal (COF) y amígdala). Esto les permitiría prestar mayor atención a la entrada sensorial de los estímulos e inhibir cualquier evaluación o reactividad emocional. Dicha situación, según concluyeron los investigadores, condiciona una menor sensibilidad al dolor.

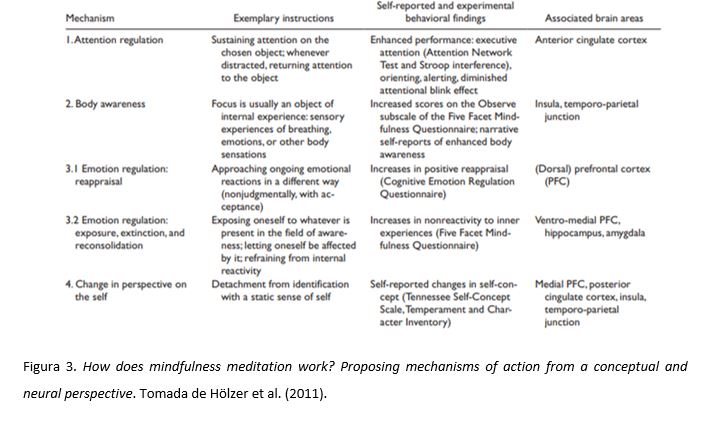

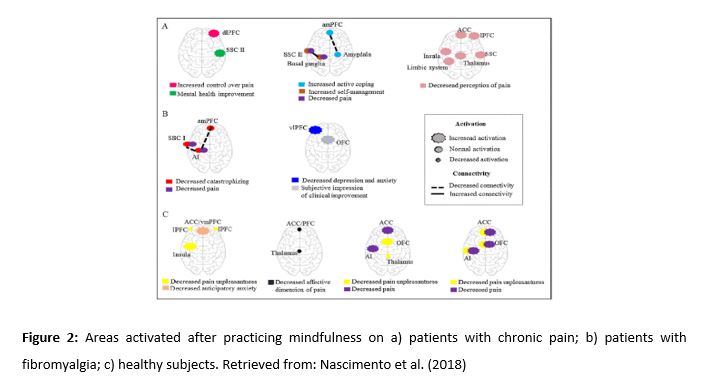

Por otro lado, Nascimento et al. (13) mostró un aumento de la activación de la CPFdl y CPFvm, en la COF, en las CSS y en el sistema límbico en pacientes con dolor crónico (Figura 2). El aumento de actividad en la CPFdl ocurriría al modificarse los mecanismos de anticipación ante el dolor agudo en pacientes con dolor crónico, aumentado la actividad en áreas relacionadas con la regulación emocional (11).

Los pacientes con dolor crónico, tras aprender mindfulness, experimentaron mejoras clínicas del dolor y autoeficacia para lidiar con este, además de una reducción en los niveles de ansiedad anticipatoria, intensidad y experiencia negativa (13). Estos hallazgos sugieren que el uso del mindfulness disminuye la probabilidad de presentar comorbilidades psiquiátricas, mejora la capacidad de aceptación de los pacientes, y aumenta su capacidad de controlar este (14). Estas modificaciones sobre el dolor se relacionarían con el descenso de actividad en la amígdala y aumento de esta en la CPF, principalmente (15).

- Comparativa del mindfulness con otros tratamientos:

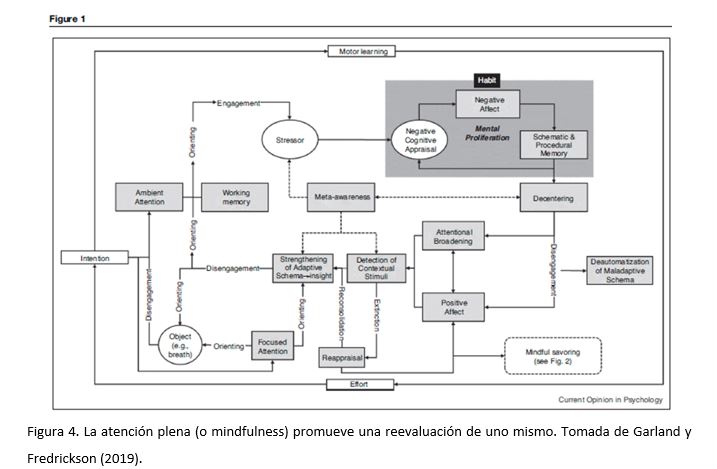

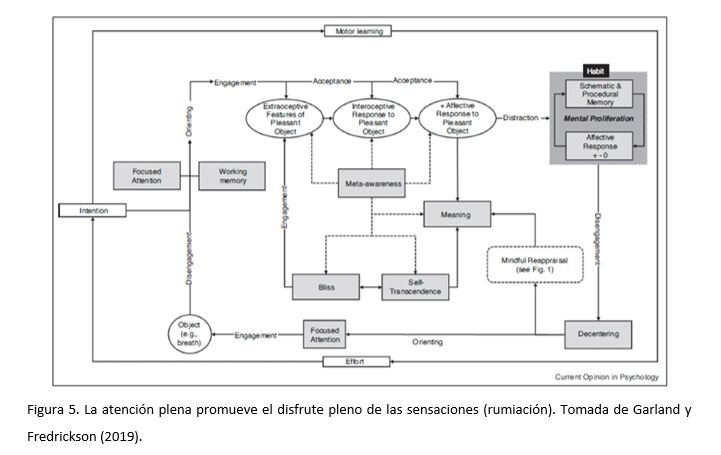

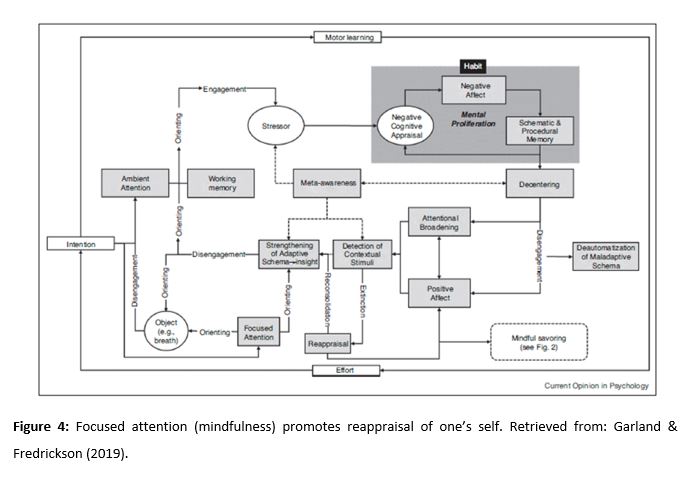

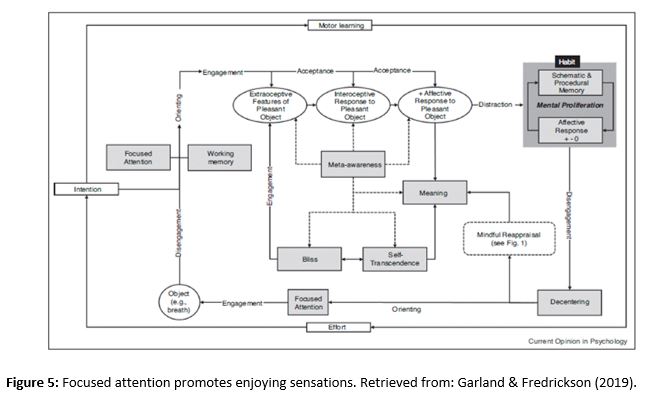

La teoría teoría Mindfulness to Meaning (TMM) se basa en dos principios: que la atención plena (o mindfulness) promueve una reevaluación de uno mismo (figura 4) y que la atención plena promueve que la persona se detenga a saborear y disfrutar de las sensaciones que los estímulos nos proporcionan (figura 5) (16).

Recientemente, los estudios han mostrado que 8 semanas de mindfulness basado en la reducción del estrés (MBRE) aumenta la eficacia de la reevaluación en un grado similar a una terapia de corte cognitivo-conductual (17).

Teniendo en cuenta estos avances, finalmente se ha creado la Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) como tratamiento para pacientes que usan indebidamente los opiáceos para el dolor crónico (18,19). MORE trata de aumentar el control cognitivo, facilitando la reevaluación y detenerse a disfrutar de las sensaciones, y trata de devolver el procesamiento de recompensa a la normalidad, valorando más las recompensas naturales a las proporcionadas por los fármacos (20). Se ha encontrado que el tratamiento MORE disminuye significativamente el dolor crónico, el deseo de fármacos y los comportamientos de consumo (18,19). Además, también se ha indicado que este tratamiento incrementa de forma muy notoria los mecanismos de la TMM; estos efectos positivos están asociados al descenso de la severidad del dolor crónico y a un menor riesgo de consumo de fármacos (18).

Por otro lado, se ha realizado una revisión sistemática de ensayos aleatorizados controlados dirigida a comprobar la eficacia del Mindfulness Basado en la Reducción de Estrés (MBRE comparada con la Terapia Cognitivo Conductual (TCC) para pacientes con sintomatología provocada por el dolor crónico. Un estudio que comparó la TCC y la MBRS no encontró diferencias significativas en mejoras para el funcionamiento físico y la mejora de la intensidad del dolor, mientras que estudios que compararon la TCC o la MBRS con grupos controles sí encontraron diferencias significativas (21). El grupo de TCC, sin embargo, dio lugar a una mejoría significativamente mayor en síntomas depresivos tras la intervención en comparación con el grupo de MBRS. En comparación con el grupo control, tanto MBRS como TCC se asociaron con mejoras generales con respecto al inicio del tratamiento (22).

Estos resultados concuerdan con los encontrados en un meta-análisis de 2016 sobre intervenciones basadas en aceptación y mindfulness para el dolor crónico y que mostraron efectos menores en la reducción de la intensidad del dolor y síntomas depresivos en comparación con los grupos control (5).

- Comparativa entre grupos de edades diferentes:

El mindfulness, como cualquier tratamiento, tiene que modificarse según las características del paciente, y algo a tener en cuenta es la edad del individuo, debido a que no solo no se tiene la misma comprensión y capacidad de entendimiento en niños (con los cuales hay que utilizar un lenguaje más simple) a diferencia de los adultos, con los que se puede utilizar un pensamiento más abstracto. A continuación, se describen una serie de estudios realizados a diferentes grupos que serán divididos en: Población pediátrica, Población adulta y Población anciana.

- Población pediátrica

Diversos estudios avalan que la incorporación de terapias no farmacológicas a tratamientos en los que es necesario el uso de medicamentos puede tener resultados mucho más efectivos en población infantil (4). Esto es debido a que un enfoque multidisciplinar en el que incluya estrategias de afrontamiento no solo mejora la calidad de vida de los niños, sino que reduce de manera considerable una posible dependencia como también una prevención a adquirir una tolerancia en un futuro. Para el tratamiento de dolor agudo (como el postquirúrgico) es necesario de una analgesia inmediata y suficiente para el manejo del dolor. Pero la integración una educación psicológica del paciente de forma previa y posterior a una cirugía puede ayudar al manejo del dolor como también a una recuperación más temprana.

Por otro lado, para el manejo de dolor crónico es necesaria una analgesia más prolongada y es más complejo de tratar, debido a que se puede llegar a sentir que la medicación recibida no es la suficiente se recurre entonces a los métodos no farmacológicos (23). En un ensayo piloto aleatorio de una intervención basada en mindfulness para mujeres adolescentes con dolor crónico, los pacientes informaron mejoras en el manejo del dolor y reducciones en los niveles de cortisol salival en la sesión posterior a la atención (24). Sin embargo, la calidad de esta investigación ha variado de ensayos controlados aleatorios a estudios piloto y están muy limitados debido a las pequeñas muestras de sujetos.

- Población adulta

En cuanto a la edad adulta podemos encontrar estudios enfocados a enfermedades como la fibromialgia o como, por ejemplo, el estudio realizado con un total de 70 mujeres (25) que cumplían los requisitos de enfermedad. Los resultados mostraron con respecto el grupo control una disminución de IL-10 y unos niveles más altos de los niveles basales CXL8 (Biomarcadores Inmunes), al igual que una modificación de esquemas y reducción significativa del dolor. Todo indica que un entrenamiento en modificación de esquemas y en técnicas de relajación (mindfulness) ha podido influir beneficiosamente en sintomatología clínica ya que describen una disminución del dolor, una mejora en inflexibilidad psicológica y una mayor calidad del sueño.

- Población anciana

Finalmente, nos encontramos ante la etapa de la tercera edad, la cual se considera a partir de una edad de 65 años. Basándonos en una revisión, en la cual diferentes estudios siguieron programas ambientadas al mindfulness (26); en estas se evaluó variables como el insomnio y función ejecutiva, pero nos centraremos en el dolor lumbar crónico (27). Los resultados mostraron que no solo hubo una mejoría en el afrontamiento al dolor, sino niveles de dolor significativamente más bajos después de la intervención, además la aceptación del dolor crónico fue mayor que en el grupo que no la recibió. Un seguimiento de 3 meses indicó que el grupo experimental siguió manteniendo unos datos significativamente mejores que el grupo control.

- Conclusiones

La caracterización de las áreas implicadas del cerebro que ayudan a las terapias derivadas del mindfulness a mejorar la sintomatología aún no está clara. Algunos autores han sugerido que las principales áreas implicadas, la CCA, la ínsula y distintas secciones de la CPF juegan un rol fundamental por su implicación en el procesamiento del dolor y la atención, y que los resultados conflictivos de los estudios responden a un proceso de aprendizaje que haría la respuesta de estas áreas más eficiente y por lo tanto con una activación más corta en practicantes más experimentados (7,8).

Respecto a su aplicación como tratamiento las terapias derivadas del mindfulness muestran tener una eficacia como mínimo igual a la de la terapia cognitivo-conductual respecto a la sintomatología comórbida del dolor crónico, pero hay escasa evidencia de que actúe sobre el dolor en sí, necesitando de terapias farmacológicas tradicionales para actuar a su máxima eficacia (17-20). Estos efectos se mantienen independientemente de los grupos de edad, si bien requieren adaptación a las características propias de los mismos (21,22,24,27). Por estas características, podría ser de particular utilidad para prevenir el abuso o reducir la dependencia de los analgésicos, dirección en la que podrían orientarse futuras líneas de investigación (2-4,23).

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, Maglione MA. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017; 51(2): 199-213. Doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2.

- Majeed MH, Ali AA, Sudak DM. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: evidence and applications. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018; 32: 79-83. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.025.

- Ball EF, Nur Shafina Muhammad Sharizan E, Franklin G, Rogozinska E. Does mindfulness meditation improve chronic pain? A systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 29(6): 359-366. Doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000417.

- Wren AA, Ross AC, D’Souza G, Almgren C, Feinstein A, Marshall A, Golianu B. Multidisciplinary pain management for pediatric patients with acute and chronic pain: a foundational treatment approach when prescribing opioids. Children. 2019; 6(2): 33. Doi:10.3390/children6020033.

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance -and mindfulness- based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016; 45(1): 5-31. Doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724.

- 6. Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011; 6(6): 537–559. Doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671.

- Hölzel BK, Ott U, Hempel H, Hackl A, Wolf K, Stark R, Vaitl D. Differential engagement of anterior cingulate cortex and adjacent medial frontal cortex in adept meditators and nonmeditators. Neurosci Lett. 2007; 421(1): 16–21. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.074.

- Brown CA, Jones AK. Meditation experience predicts less negative appraisal of pain: electrophysiological evidence for the involvement of anticipatory neural responses. Pain. 2010; 150(3): 428–438. Doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.017.

- Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006; 62(3): 373–386. Doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237.

- Zeidan F, Grant JA, Brown CA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: Evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain. Neurosci Lett. 2012; 520(2): 165–173. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082.

- Bilevicius E, Kolesar TA, Kornelsen J. Altered neural activity associated with mindfulness during nociception: a systematic review of functional MRI. Brain Sci. 2016; 6(2): 14. Doi: 10.3390/brainsci6020014.

- Grant JA, Zeidan F. Employing pain and mindfulness to understand consciousness: a symbiotic relationship. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 192–197. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.025.

- Nascimento SS, Oliveira LR, DeSantana, JM. Correlations between brain changes and pain management after cognitive and meditative therapies: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Complement Ther Med. 2018; 39: 137-145. Doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.06.006.

- Greeson JM, Chin GR. Mindfulness and physical disease: a concise review. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 204-210. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.014.

- Reive C. The biological measurements of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction: a systematic review. EXPLORE. 2019. Doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.01.001. In press

- Garland EL, Fredrickson BL. Positive psychological states in the arc from mindfulness to self-transcendence: extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and applications to addiction and chronic pain treatment. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 184-191. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.01.004.

- Goldin PR, Morrison A, Jazaieri H, Brozovich F, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016, 84(5): 427-437. Doi: 10.1037/ccp0000092.

- Garland EL, Hanley AW, Riquino MR, Reese SE, Baker AK, Salas K, Yack BP, Bedford CE, Bryan MA, Atchley RM, Nakamura Y, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement reduces opioid misuse risk via analgesic and positive psychological mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019. In press

- Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014; 82(3): 448-459. Doi: 10.1037/a0035798.

- Garland EL. Restructuring reward processing with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: novel therapeutic mechanisms to remediate hedonic dysregulation in addiction, stress, and pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016, 1373(1): 25-37. Doi: 10.1111/nyas.13034.

- Khoo EL, Small R, Cheng W, Hatchard T, Glynn B, Rice DB, Skidmore B, Kenny S, Hutton B, Poulin PA. Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019; 22(1): 26-35. Doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300062.

- Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Anderson ML, Hawkes RJ, Hansen KE, Turner JA. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016; 315(12): 1240-1249. Doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2323.

- Garland EL. Disrupting the downward spiral of chronic pain and opioid addiction with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: a review of clinical outcomes and neurocognitive targets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014; 28(2): 122–129. Doi: 10.3109/15360288.2014.911791.

- Chadi N, McMahon A, Vadnais M, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Djemli A, Dobkin PL, Lacroix J, Luu TM, Haley N. Mindfulness-based intervention for female adolescents with chronic pain: a pilot randomized trial. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 25(3); 159–168.

- Andrés-Rodríguez L, Borràs X, Feliu-Soler A, Pérez-Aranda A, Rozadilla-Sacanell A, Montero-Marin J, Maes M, Luciano JV. Immune-inflammatory pathways and clinical changes in fibromyalgia patients treated with Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2019. Doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.02.030. In press

- Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy with older adults: a qualitative review of randomized controlled outcome research. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011; 124(2): 102–119. Doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x.

- Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008; 134(3): 310-319. Doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038.

Mindfulness and Chronic Pain: A Review on Cognitive, Neurological and Behavioral Changes Related to Pain

This review aims to gather the most relevant data regarding mindfulness and its effectiveness towards chronic pain treatment. In order to do so, we carried out a bibliographical study on the areas of the brain which are activated by chronic pain and the influence of mindfulness on these areas. In addition to this, we studied the effectiveness of mindfulness by itself and, in comparison with other non-pharmacological therapies, its effects on patients depending on their age. Despite the apparent contradictions in its action mechanisms, mindfulness seems to be as effective as other non-pharmacological therapies when used as an adjuvant therapy, regardless of the age group. Thus, it could be useful for preventing abuse or reducing dependence on analgesics.

Keywords: chronic pain, mindfulness, neuroimaging, pain management, alternative therapies, pediatric pain, geriatric pain.

Introduction

Chronic pain is often defined as any pain lasting longer than 3 months, or any pain persisting after the normal time for tissue healing (1). It can worsen progressively and appear intermittently, thus decreasing the patient’s quality of life. It is estimated 5.5%-33% of the global adult population suffer from chronic pain. Furthermore, adolescents and children can also suffer from chronic pain. The number of people affected has increased over the years due to the population aging (2). This leads to economic costs for both the healthcare system and the professional careers of the patients, as it can result in a loss of productivity (1) or even in workplace absenteeism (3), consequently affecting the employer.

Over the last two decades, one of the most common treatments used for chronic pain has been opioid prescriptions (4), since they are effective analgesics. Nevertheless, due to an exponential growth in the prescription of these drugs, the death rate by overdose has increased (2), as well as the addiction likelihood. Thus, researchers are exploring the use of combined treatments (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) in order to reduce the use of opioids (4). Among the non-pharmacological treatments, certain alternative therapies can be found. Most of these have been proved to be effective in treating chronic pain and are cheaper, thus reducing economical costs. These alternative therapies include mindfulness-based interventions, the cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the acceptance and commitment therapy, acupuncture, and hypnosis (4). All of these treatments are able to reduce pain perception and improve the functionality of the patient. In addition, other types of therapy, such as occupational therapy, physical therapy, and physical exercise, have been effective in chronic pain treatment (2). In this paper, we focus on mindfulness-based interventions.

Mindfulness-based interventions (e.g. yoga, meditation, stress reduction) are based on the non-judgmental awareness of the present moment (2), by focusing on it and accepting it (1). This allows patients to cope better when they experience pain (3). Accordingly, the aim of this practice is to reduce pain perception and improve the patient’s quality of life. Although it is often impossible to eradicate chronic pain, patients can learn skills to help them live a productive life, even when experiencing a feeling of discomfort (2).

The role of mindfulness is promising, but there are certain limitations because only a small number of studies have been carried out in this line. These limitations include the variability of the population and the different techniques that can be used (3) as well as the low quality of these studies (5), making their standardization and generalization more difficult.

Despite these limitations, some advantages have been found, including the improvement of symptoms; the lack of abuse or dependence; and the improvement of comorbid conditions, such as anxiety or depression (2, 3). In this review, we aim to show alternative treatments which carry no risk of addiction for patients who are suffering from chronic pain. The main focus is set on mindfulness and its actual effectiveness as a treatment.

- Neurophysiology and neuroimaging

The applications of mindfulness are well established. However, its action mechanisms are still unclear (Figure 1). In order to explain how these therapies work, four interrelated components were proposed (Figure 3): attention regulation, body awareness, emotion regulation, and change in perspective on the self (6). The first three components will be thoroughly explored. Afterwards, the elements that constitute pain, how they are represented in the brain, and how mindfulness affects the areas in which they are involved in will also be studied.

The action components of mindfulness and pain are explained as follows:

2.1. Attention regulation

Attention regulation is defined as the process of focusing attention on an object, recognizing distractions and going back to focusing on the object. Many studies (7, 8) suggest a greater activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the secondary somatosensory cortex (SII). Both areas are involved in the process of attention regulation.

2.2. Body awareness

Body awareness refers to the process of focusing on a structure or task inside the body. There are two possible mechanisms involved in the increase of body awareness. The first one would involve the activation of the right anterior insula and the long-term concentration of gray matter within this area. The other possible mechanism would involve the regulation of the amygdala via the ACC and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC). However, short-term studies suggest that these changes start at the temporoparietal junction, and not at the insula (6, 9).

2.3. Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation occurs at a cognitive level (focused attention). It is based on playing close attention to stimuli and to changes, and how we respond to them. This can be achieved either by the reappraisal of the stimulus (i.e. interpreting the stimulus in a positive way) or by the extinction of the stimulus (i.e. reverting the response to the stimulus). Another way in which emotion regulation occurs at a behavioral level is by inhibiting the expression of certain behaviors in response to the stimulus (6).

Two systems have been suggested: (1) a system that involves the lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC) and the ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) and whose functions are, respectively, managing selective attention and participating in the inhibition of a response; and (2) a system that involves the ACC (6, 10).

2.4. Pain

According to Bilevicius et al. (11), pain is composed of three factors: (1) a sensorial factor, which activates the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices (SI and SII) and the thalamus; (2) a cognitive factor, which activates the prefrontal cortex (PFC); and (3) a motivational-affective factor, which increases the activity in the ACC and in the anterior and posterior insulae. Mindfulness acts directly or indirectly in many of these factors, as previously seen.

2.5. Neuroimaging results

A study carried out by Grant et al. (12) revealed that experienced meditators show a greater activation of the insula, the thalamus and the midcingulate cortex, as well as a minor activation of the areas of the brain that are responsible for emotion control (the medial prefrontal cortex [mPFC], the orbitofrontal cortex [OFC], and the amygdala). This would allow meditators to pay more attention to the sensory input of stimuli and to inhibit any emotional appraisal or reactivity. This situation, according to the researchers, leads to a diminished sensitivity to pain.

On the other hand, Nascimento et al. (13) reported an increase in the activation of the dlPFC, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), the OFC, the SI and SII, and the limbic system in patients suffering from chronic pain (Figure 2). The increase of activity in the dlPFC in the patients occurs when action mechanisms are modified by acute pain. Therefore, this leads to an increase in activity in areas involved in emotion regulation (11).

After having learnt about mindfulness, patients suffering from chronic pain experienced improvements in clinical measures of pain and self-efficacy to deal with chronic pain. Patients also experienced a decrease in levels of anticipatory anxiety, pain intensity and the negative experience of pain (13). These findings suggest that the use of mindfulness decreases the likelihood of presenting psychiatric comorbidities and increases the patient’s capabilities of acceptance and pain control (14). These changes in the experience of pain are mainly associated with a decrease in amygdala activity and an increase in PFC activity (15).

- Mindfulness compared with other treatments

The mindfulness-to-meaning theory (MMT) is based on two premises: (1) the principle that focused attention (mindfulness) promotes reappraisal of one’s self (Figure 4); and (2) the principle that focused attention encourages the individual to enjoy the sensations caused by stimuli (Figure 5) (16).

Recently, certain studies have shown that a period of 8 weeks of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) increases the efficacy of reappraisal to a similar degree as cognitive-behavioral therapy (17).

Taking these advances into account, Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) has been created as a treatment for those patients who misuse opioids in order to treat their chronic pain (18, 19). MORE aims at increasing cognitive control, facilitating reappraisal and enjoying pleasant sensations. It also aims at returning the patients’ reward processing back to baseline levels, so that they value natural rewards more than drug-based rewards (20). MORE has been found to significantly decrease chronic pain and drug-seeking behavior (18, 19). In addition, this treatment has also been found to significantly increase MMT mechanisms. These positive effects are linked to a decrease in chronic pain intensity and to a lower risk of drug consumption (18).

Moreover, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials was carried out, aimed at confirming the efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) compared to that of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) on patients with symptoms caused by chronic pain (21). A study compared CBT and MBSR and did not find any significant differences between them in relation to the improvement of physical functioning or the reduction of pain intensity (21). The CBT group, however, showed more signs of improvement on depressive symptoms after the treatment compared to the MBSR group. When compared to the control group, both CBT and MBSR were associated with general improvements after the intervention (22).

These results are consistent with those found in a meta-analysis carried out in 2016 and focused on interventions for chronic pain based on acceptance and mindfulness, which showed minor effects on the reduction of pain intensity and depressive symptoms compared to the control groups (5).

3.1. Comparison between different age groups

Mindfulness, like any other treatment, must be adapted according to the characteristics of the patient. The age of the participants has to be taken into account, since children do not have the same comprehension and understanding as adults do. Working with children requires a simpler language, whilst adults are capable of more abstract thinking. A series of studies on different groups are described below and are divided as follows: pediatric population, adult population and geriatric population.

3.1.1. Pediatric population

Several studies confirm that including non-pharmacological therapies in treatments that require drugs can have much more effective results on pediatric population (4). This is due to the fact that a multidisciplinary approach including coping strategies not only improves children quality of life, but also significantly reduces the possibility of dependence and prevents developing a future tolerance. Immediate and sufficient analgesia are necessary to manage acute pain (such as post-operative pain). However, including psychological education of the patient pre- and post-surgery can help manage the pain and speed up the recovery process.

On the other hand, chronic pain management requires a more prolonged analgesia and is more complex to treat, since the patient can feel that pharmacological treatment is insufficient, thus resorting to non-pharmacological methods (23). In a randomized pilot study of an intervention based on mindfulness for adolescent women suffering from chronic pain, the patients reported an improvement in pain management and a decrease in salivary cortisol levels during the post-treatment session (24). However, the quality of this line of research has varied from randomized controlled trials to pilot studies and is very limited due to a small sample size.

3.1.2. Adult population

Regarding adult population, there are studies which have focused on medical conditions such as fibromyalgia, e.g. a study which was carried out on a total of 70 women who met the criteria of the illness (25). In comparison with the control group, the results showed a reduction of IL-10 and higher baseline levels of CXCL8 (immune biomarkers), as well as a change in schemes and a significant reduction of chronic pain. It appears that training in schema modification and relaxation techniques (such as mindfulness) has been able to positively influence clinical symptomatology, as patients reported a decrease in pain, an improvement in psychological inflexibility, and a better quality of sleep.

3.1.3. Geriatric population

Finally, geriatric population includes participants aged over 65. A review of a series of studies which followed mindfulness-based programs analyzed variables such as insomnia and executive function, among others (26). However, the focus is set on chronic back pain (27). The results showed not only an improvement in pain management, but also significantly lower post-treatment pain levels. In addition, the acceptance of chronic pain was higher than in the group that did not receive the mindfulness-based treatment. A 3-month follow-up session showed that the experimental group maintained significantly better results than the control group.

- Conclusions

The way in which the associated areas of the brain allow mindfulness-based therapies to improve symptomatology is still unclear. Some authors have suggested that the main associated areas (i.e. the ACC, the insula, and several sections of the PFC) may play a key role because they are involved in pain and attention processing. They argue that the mixed results are due to a learning process which would make the response of these areas more efficient, thus causing more experienced users to experience activation at a faster rate (7, 8).

Regarding the implementation of mindfulness-based therapies as treatment, they have been shown to be at least as efficient as cognitive-behavioral therapy, with regard to comorbid symptoms of chronic pain. However, there is limited evidence of mindfulness-based therapies influencing pain itself, as it requires traditional pharmacological treatments to reach maximum efficacy (17-20). These effects are constant regardless of the age group, but they must be adapted to the characteristics of each group (21, 22, 24, 27). Due to these characteristics, these therapies could be particularly useful to prevent or reduce the abuse and dependence on analgesics. Future work in this line of research is suggested (2-4, 23).

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, Maglione MA. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017; 51(2): 199-213. Doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2.

- Majeed MH, Ali AA, Sudak DM. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: evidence and applications. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018; 32: 79-83. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.025.

- Ball EF, Nur Shafina Muhammad Sharizan E, Franklin G, Rogozinska E. Does mindfulness meditation improve chronic pain? A systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 29(6): 359-366. Doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000417.

- Wren AA, Ross AC, D’Souza G, Almgren C, Feinstein A, Marshall A, Golianu B. Multidisciplinary pain management for pediatric patients with acute and chronic pain: a foundational treatment approach when prescribing opioids. Children. 2019; 6(2): 33. Doi:10.3390/children6020033.

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance -and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016; 45(1): 5-31. Doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724.

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011; 6(6): 537–559. Doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671.

- Hölzel BK, Ott U, Hempel H, Hackl A, Wolf K, Stark R, Vaitl D. Differential engagement of anterior cingulate cortex and adjacent medial frontal cortex in adept meditators and non-meditators. Neurosci Lett. 2007; 421(1): 16–21. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.074.

- Brown CA, Jones AK. Meditation experience predicts less negative appraisal of pain: electrophysiological evidence for the involvement of anticipatory neural responses. Pain. 2010; 150(3): 428–438. Doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.017.

- Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006; 62(3): 373–386. Doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237.

- Zeidan F, Grant JA, Brown CA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: Evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain. Neurosci Lett. 2012; 520(2): 165–173. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082.

- Bilevicius E, Kolesar TA, Kornelsen J. Altered neural activity associated with mindfulness during nociception: a systematic review of functional MRI. Brain Sci. 2016; 6(2): 14. Doi: 10.3390/brainsci6020014.

- Grant JA, Zeidan F. Employing pain and mindfulness to understand consciousness: a symbiotic relationship. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 192–197. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.025.

- Nascimento SS, Oliveira LR, DeSantana, JM. Correlations between brain changes and pain management after cognitive and meditative therapies: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Complement Ther Med. 2018; 39: 137-145. Doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.06.006.

- Greeson JM, Chin GR. Mindfulness and physical disease: a concise review. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 204-210. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.014.

- Reive C. The biological measurements of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction: a systematic review. EXPLORE. 2019. Doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.01.001. In press

- Garland EL, Fredrickson BL. Positive psychological states in the arc from mindfulness to self-transcendence: extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and applications to addiction and chronic pain treatment. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019; 28: 184-191. Doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.01.004.

- Goldin PR, Morrison A, Jazaieri H, Brozovich F, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016, 84(5): 427-437. Doi: 10.1037/ccp0000092.

- Garland EL, Hanley AW, Riquino MR, Reese SE, Baker AK, Salas K, Yack BP, Bedford CE, Bryan MA, Atchley RM, Nakamura Y, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement reduces opioid misuse risk via analgesic and positive psychological mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019. In press

- Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014; 82(3): 448-459. Doi: 10.1037/a0035798.

- Garland EL. Restructuring reward processing with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: novel therapeutic mechanisms to remediate hedonic dysregulation in addiction, stress, and pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016, 1373(1): 25-37. Doi: 10.1111/nyas.13034.

- Khoo EL, Small R, Cheng W, Hatchard T, Glynn B, Rice DB, Skidmore B, Kenny S, Hutton B, Poulin PA. Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019; 22(1): 26-35. Doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300062.

- Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Anderson ML, Hawkes RJ, Hansen KE, Turner JA. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016; 315(12): 1240-1249. Doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2323.

- Garland EL. Disrupting the downward spiral of chronic pain and opioid addiction with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: a review of clinical outcomes and neurocognitive targets. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014; 28(2): 122–129. Doi: 10.3109/15360288.2014.911791.

- Chadi N, McMahon A, Vadnais M, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Djemli A, Dobkin PL, Lacroix J, Luu TM, Haley N. Mindfulness-based intervention for female adolescents with chronic pain: a pilot randomized trial. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 25(3); 159–168.

- Andrés-Rodríguez L, Borràs X, Feliu-Soler A, Pérez-Aranda A, Rozadilla-Sacanell A, Montero-Marin J, Maes M, Luciano JV. Immune-inflammatory pathways and clinical changes in fibromyalgia patients treated with Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2019. Doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.02.030. In press

- Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy with older adults: a qualitative review of randomized controlled outcome research. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011; 124(2): 102–119. Doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x.

- Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008; 134(3): 310-319. Doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038.

AMU 2019. Volumen 1, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

15/04/2019 22/04/2019 31/05/2019

Cita el artículo: Morato-Gabao C, Navares-López D, Pérez-Martínez R, Romero-de-los-Reyes L, Solier-López L. Dolor neuropático localizado: una revisión narrativa. AMU. 2019; 1(1): 139-77