Ariana Guiomar-Córdova 1; Magdalena Bustos-Romano 1; Daniel Sánchez-Correa 1

1 Facultad de Ciencias (Biología), Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Sofía Antequera-Manzano 2; Beatriz Arellano-Romero 2; Samuel De la Torre-Galán 2; Carmen Gámez-Salazar 2; Clara Sofía GilOrtega-Barahona 2; Amanda Inés Hernández-García 2; Francisco José Villena-Rodríguez 2

2 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

En esta revisión no sistemática se han recogido los datos aportados por la evidencia científica de las secuelas neurológicas de los pacientes, entre 18 y 65 años, con COVID-19. Se ha identificado que la principal entrada del SARS-CoV-2 se produce mediante el receptor ACE2, presente en numerosas células del organismo. El virus atraviesa la barrera hematoencefálica a través de las células endoteliales vasculares o inmunitarias, los canales del nervio óptico y olfatorio, y la transferencia transináptica. En el sistema nervioso central, la tormenta de citoquinas tiene como consecuencia final la privación de oxígeno a las células neuronales, que repercute a largo plazo en la posible aparición de trastornos neurodegenerativos, como las encefalopatías. Los estudios preliminares acerca del tratamiento sugieren un abordaje sintomático y proponen el uso de algunos fármacos, como el Adamantane. Por tanto, la cognición podría verse afectada como secuela de la COVID-19 en algunos pacientes, y ello podría estar relacionado con el nivel inflamatorio producido por la infección.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, cognición, ACE2, proteína S, daños neuronales, secuelas neurológicas.

Keywords: COVID-19, cognition, ACE2, spike protein, neuronal injury, neurological sequelae.

Introducción

En diciembre de 2019, se identificó en el mercado de mariscos de Huanan en Wuhan, en la provincia de Hubei de China, la presencia del agente SARS-CoV-2 (1,2), un virus que causaba una neumonía atípica de origen desconocido y dolores musculares, entre otros síntomas (2). Desde entonces, el número de casos ha aumentado exponencialmente en diferentes países del planeta (1). La OMS lo declaró como pandemia el 11 de marzo de 2020 (2). A fecha de 28 de marzo de 2021, se han confirmado 126 607 206 casos positivos y un total de 2 776 023 fallecidos en todo el mundo, de acuerdo con los datos aportados por la Universidad Johns Hopkins (3).

El SARS-CoV-2 es un nuevo betacoronavirus causante de la COVID-19 (4). El tiempo medio de incubación se estima que puede ser aproximadamente de dos días, aunque puede variar de uno a cuatro días (5). La sintomatología más común que provoca este microorganismo incluye fiebre, tos seca, cansancio, cefalea, anosmia, hiposmia, ageusia, disnea y dolor torácico, entre otros (6–8). La alteración del estado mental fue la segunda manifestación más habitual (9). Los daños cerebrovasculares y el deterioro de la conciencia se desarrollaron en un período medio posterior al ingreso de ocho a diez días. El resto de las manifestaciones neurológicas ocurrieron dentro de un período medio de uno a dos días posteriores al ingreso. Las manifestaciones neurológicas fueron más frecuentes en pacientes con infección grave por COVID-19 que en aquellos con enfermedad no grave (10). Los déficits más comunes fueron la alteración del estado mental, con manifestaciones como delirios (13), una fuerte alteración de la personalidad, cognición o conciencia, y una alteración del sistema nervioso periférico (SNP) (9). Además, se ha descrito la implicación de este agente en síntomas de mayor gravedad, tales como dificultad en el habla o el movimiento, convulsiones, confusión e incluso la muerte (11,12).

El objetivo de esta revisión no sistemática fue recoger los datos aportados por la evidencia científica de las secuelas neurológicas de los pacientes con COVID-19. Además, se han estudiado los posibles mecanismos de entrada del virus tanto en las células como en el organismo a través de vías de difusión al sistema nervioso central (SNC), y si existe algún tratamiento disponible actualmente.

Métodos

En esta revisión narrativa se han considerado los estudios encontrados utilizando la ecuación de búsqueda “cognitive sequelae covid” en la base de datos de Medline. El criterio de selección fue escoger pacientes con edades comprendidas entre los dieciocho y los sesenta y cinco años. Se han estudiado las secuelas cognitivas que tiene un paciente post-COVID en comparación con la respuesta cognitiva normal en pacientes que no han pasado la infección. Se han recogido todos los estudios relacionados con este tema publicados en el último año.

Entrada en la célula: unión del SARS-CoV-2 mediante el receptor ACE2

Muchas enfermedades crónicas degenerativas podrían ser consecuencia del daño neuronal causado por la COVID-19. A pesar de los posibles efectos directos o indirectos de la enfermedad, la COVID-19 puede dejar daños permanentes en el SNC (14). Una de las áreas más vulnerables al daño isquémico en COVID-19 y de vital importancia para la función cognitiva es la sustancia blanca cerebral. El efecto destructivo acumulativo de la isquemia o hemorragia cerebral multifocal junto a las complicaciones que surgen tras haber pasado la enfermedad, como pueden ser la disfunción de la barrera endotelial y de la hematoencefálica (BHE), y la regulación ascendente de citocinas proinflamatorias en el cerebro, pueden aumentar considerablemente el riesgo de daño cerebral crónico (15). Además, se establece una posible relación entre el deterioro cognitivo y la neurodegeneración con el síndrome de dificultad respiratoria aguda (SDRA) (16). Para aquellos pacientes con COVID-19 de edad avanzada o con patologías previas como hipertensión, diabetes y una enfermedad cerebrovascular subyacente, se ha observado una mayor incidencia informada de esta, aunque también se han dado casos en adultos jóvenes con COVID-19 (15).

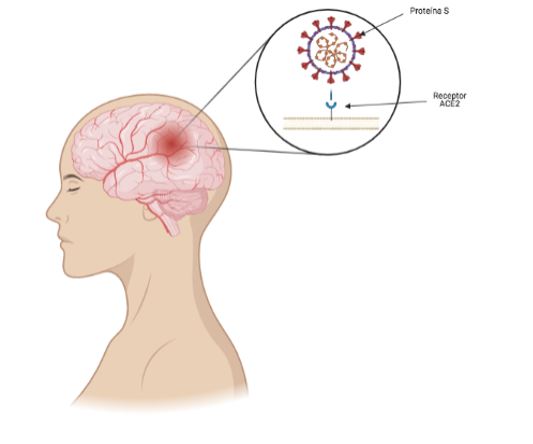

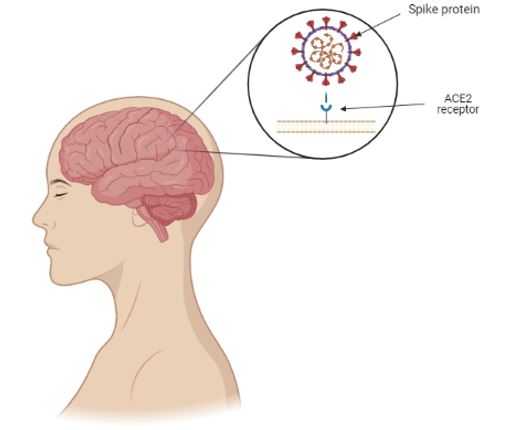

La interacción de la proteína S del SARS-CoV-2 junto con el receptor ACE-2 hace que el virus entre en la célula, lo que permite su infección. La distribución de la expresión de ACE2 en diferentes sitios en tejidos cerebrales animales y humanos se expresa ampliamente en neuronas, astrocitos y oligodendrocitos en todo el cerebro (14) (Figura 1). Gracias a los estudios post mortem se han descubierto tres grandes hallazgos:

- El receptor ACE-2, el principal receptor del SARS-CoV-2, se expresa ampliamente en las células endoteliales microvasculares del cerebro, en los pericitos en todo el cuerpo y en el cerebro (14,15).

- La integridad de la BHE puede ser dañada directamente por la proteína S con distintos grados de severidad (14).

- La proteína S induce la inflamación de las células endoteliales microvasculares que provocan una disfunción de la BHE (14).

Figura 1. Ilustración de la unión de la proteína S del SARS-CoV-2 al receptor ACE2 presente en el sistema nervioso central.

Existen dos maneras por las que el virus se une al receptor ACE2:

- Vía de las células endoteliales vasculares: Las células endoteliales vasculares regulan la permeabilidad de la BHE a través de uniones estrechas. En estas uniones hay una amplia expresión de ACE2 que proporciona el mecanismo molecular por el cual el SARS-CoV-2 penetra en la BHE e invade el cerebro. El virus se une al receptor ACE2 y entra en las células endoteliales vasculares por endocitosis y exocitosis, logrando así su transferencia entre células. Sin embargo, el virus no se replica durante el proceso de transferencia de células transendoteliales, sino que la replicación viral se retrasa hasta que alcanza sus células diana, como las neuronas o células de la glía, y se une al ACE2 antes de comenzar a replicar (14).

- Vía de las células inmunitarias: Las células inmunitarias funcionan como una vía para que el SARS-CoV-2 cruce la BHE (17) mediante un mecanismo que se conoce como “caballo de Troya”. Se requieren dos condiciones: la primera es que las células inmunes expresen ACE2, y la segunda es que tiene que estar en condiciones en las que el virus no se replique. Además, el patógeno puede ingresar al citoplasma de los macrófagos al unirse al receptor en la superficie utilizando el mecanismo del “caballo de Troya” (14).

Métodos de entrada en el organismo

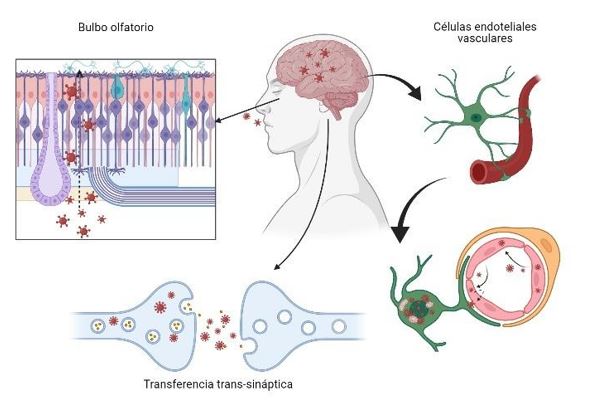

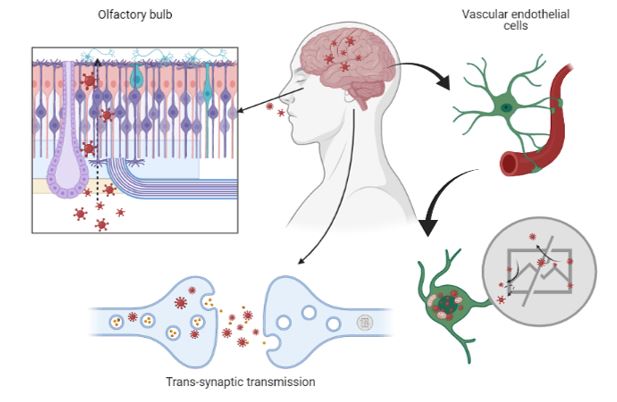

Los principales sitios de entrada del SARS-CoV-2 a nuestro organismo son las vías respiratorias. Esto resulta en una neumonía, seguida de fibrosis y deterioro crónico de la función pulmonar. La infección por dicho patógeno afecta al SNC y al SNP, dañando así directa o indirectamente tanto las neuronas como las células gliales, lo que provoca patologías neurológicas (18) que pueden dar lugar a secuelas permanentes a largo plazo. El transporte del virus a través del bulbo olfatorio, que implica anosmia, es una posible ruta potencial para la neuroinvasión; no obstante, la vasculatura cerebral juega un papel de mayor importancia en la entrada del virus al SNC (15). La alteración de la BHE por el SARS-CoV-2 y su posterior entrada al cerebro favorecen la formación de microtrombos mortales e incluso la aparición de encefalitis, asociada con esta enfermedad (14). Esta asociación respalda hipótesis plausibles para la aparición de secuelas neurológicas a largo plazo. Existen distintas vías por las que el SARS-CoV-2 puede penetrar al cerebro, cruzando la BHE:

- Canales del nervio óptico y olfatorio (18);

- Transferencia transináptica (19);

- Células endoteliales vasculares (14).

El nervio olfatorio alberga a las células sustentaculares, que mantienen la integridad del sentido del olfato, y las células madre en el epitelio olfativo. Dichas células expresan altamente ACE2 y serina proteasa 2 transmembrana (TMPRSS2), lo que puede conducir a la unión del SARS-CoV-2 al bulbo olfatorio y las células sustentaculares, seguido de su viaje al cerebro (14).

El SARS-CoV-2 ingresa al sistema nervioso central a través de dos rutas: la vía olfativa y la vía de la barrera hematoencefálica. El virus puede pasar al SNC por endocitosis, puesto que posee gran permeabilidad vascular inducida por citocinas inflamatorias y una transferencia indirecta a través del mecanismo de “caballo de Troya”. Después de unirse a su receptor de membrana, el ACE2, el patógeno es engullido en el citosol neuronal y se conectará con la enzima convertidora de angiotensina en el citosol. Tanto el virus como la tormenta de citocinas pueden destruir la vaina de mielina de las neuronas, lo que da lugar a una neuropatología aguda y crónica (14) (Figura 2).

Figura 2. Ilustración de los principales mecanismos de entrada del SARS-CoV-2 al sistema nervioso central.

Canales del nervio óptico y olfatorio

Las citocinas inflamatorias y la proteína C reactiva (PCR) desempeñaron un papel importante en el desarrollo de las manifestaciones del SARS: las partículas de SARS-CoV-2 se diseminan en la mucosa respiratoria e infectan a otras células; esto provoca cambios en las células inmunitarias periféricas y una cascada de respuestas inmunitarias, lo que da lugar a una producción de citocinas que resulta perjudicial, ya que la activación de la inflamación está ligada a la disfunción cognitiva (16).

Los estudios post mortem sobre la patología cerebral de los pacientes con COVID-19 y el uso de un modelo de microfluidos 3D avanzado de la BHE humana identificaron que el receptor ACE2 junto con la proteína S del SARS-CoV-2 se expresa en las células microvasculares del cerebro. Dicha proteína puede dañar la integridad de la BHE de distintas maneras además de inducir respuestas inflamatorias a las células microvasculares, cambiando así la función de la barrera. Estos hallazgos apoyan que el SARS-CoV-2 puede alterar la BHE y entrar al cerebro, lo que produce síntomas neurológicos, la formación de microtrombos fatales e incluso la aparición de encefalitis. De esta manera, puede llegar a ser una base potencial para la aparición de secuelas neurológicas a largo plazo (14).

Uno de los desencadenantes producidos por el ingreso del SARS-CoV-2 al SNC a través del bulbo olfatorio sería la pérdida del olfato, la cual desencadenaría ciertos trastornos neurodegenerativos. Esto se debe a la pérdida de neurotransmisores producida por la muerte neuronal. A continuación de esta entrada, el virus puede comenzar una replicación viral y activar así proteínas proinflamatorias. Esto también podría derivar en una pérdida de neuronas de dopamina (DA) o en la agregación de formas de fibrillas amiloides, producido por mediadores oxidativos (18).

Transferencia transináptica

Cuando el SARS-CoV-2 se une al receptor ACE2, llega al sistema nervioso central mediante transporte axonal. Al llegar a la hendidura sináptica, la exocitosis mediada por el recubrimiento de la membrana y la endocitosis, y el transporte de vesículas, dan como resultado la transferencia trans-sináptica del virus de neurona a neurona, y de neurona a célula satélite. Además, el rápido transporte axonal intracelular proporciona una base estructural para una mayor transferencia del virus (14).

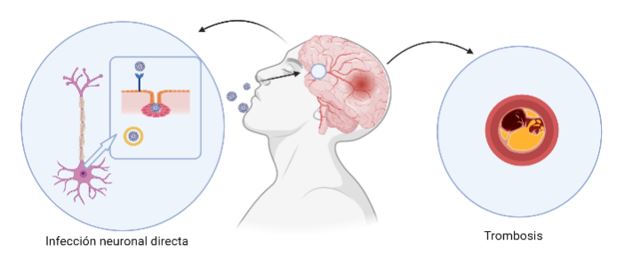

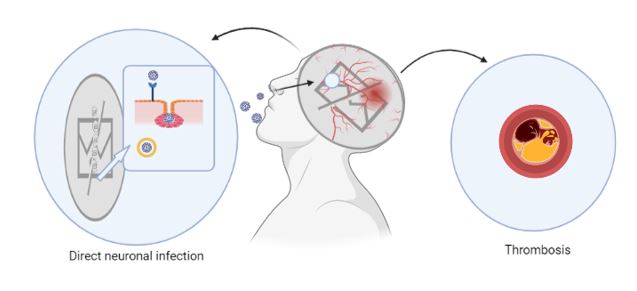

Cómo afecta al sistema nervioso

Independientemente del método de invasión que utilice el SARS-CoV-2, cuando llega a su destino se replica y utiliza sus mecanismos víricos para causar muerte celular o deterioro funcional. Su rápida replicación, el daño celular directo, la activación del sistema inmunológico y los mediadores inflamatorios (incluidas las citocinas) son las causas de los síntomas agudos de COVID-19 y pueden explicar las secuelas a largo plazo de la infección por SARS-CoV-2. El aumento de mediadores inflamatorios, la denominada tormenta de citocinas, puede explicar el daño multiorgánico encontrado en algunos pacientes con COVID-19 y también los efectos del SARS-CoV-2 en el SNC. Esta tormenta de citocinas proinflamatorias aumenta la permeabilidad vascular y, además, puede provocar una coagulación sanguínea anormal e insuficiencia multiorgánica. Estas citocinas también pueden generar un aumento de la permeabilidad microvascular en el SNC, que facilita la entrada del virus a través de la BHE, lo cual podría promover la formación de trombos mediante la activación del sistema de coagulación (14).

Debido a la autoinmunidad que se genera tras la infección, se produce un daño cerebral que se puede asociar a la infección por SARS-CoV-2. También se conoce que este ataque puede producir encefalopatías, algunas con síntomas psicóticos y otras con neurológicos. Nuestro cerebro está protegido por la BHE y se hace vulnerable ante el ataque inmune. Esto no suele ser muy común entre los pacientes por COVID-19.

La neumonía y la isquemia son dos de las consecuencias principales de la infección por SARS-CoV-2, que da lugar a una hipoxia altamente moderada que afecta al cerebro y produce severos efectos negativos en los casos más graves. Estos efectos negativos están asociados con:

– la reducción del oxígeno arterial, el cual nos provoca una disminución neuronal;

– la oxidación de las neuronas, producida por la hipoxia.

Como consecuencia de la inflamación producida por el COVID, aumenta la fibronectina, la cual facilita la creación de coágulos, y una gran parte de pacientes infectados por SARS-CoV-2 han presentado estas complicaciones. Debido a esto, podemos desarrollar con mayor probabilidad enfermedades neurodegenerativas (19) (Figura 3).

Figura 3. Ilustración de los daños potencialmente producidos por el SARS-CoV-2 en el sistema nervioso central.

Secuelas a largo plazo

Es posible que los coronavirus persistan en células residentes del SNC y puedan ser cofactores relacionados con el desarrollo de manifestaciones neurológicas a largo plazo en sujetos genéticamente predispuestos. Diversos coronavirus se han identificado mediante técnicas serológicas en una gran variedad de patologías neurológicas, como la enfermedad de Parkinson, la esclerosis lateral amiotrófica, la esclerosis múltiple y la neuritis óptica. Los coronavirus 229E, 293 y OC43 se han aislado del líquido cefalorraquídeo y el cerebro de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple. Se ha descrito una prevalencia significativamente mayor de coronavirus OC43 en el cerebro de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple que en un grupo control. Además, la respuesta inmune tras la infección podría participar en la inducción de brotes de esclerosis múltiple en individuos susceptibles (20).

Dado que algunos de los efectos del SARS-CoV-2 podrían aparecer meses o años después de la infección, sería conveniente realizar un seguimiento constante de los pacientes que han sufrido la COVID-19. La tormenta de citocinas causada por la infección puede causar pequeños accidentes cerebrovasculares puntuales sin causar déficits neurológicos notables. Cuando un paciente ha superado el virus puede experimentar problemas de memoria, atención o velocidad de procesamiento lenta. Por lo tanto, se recomienda a estos pacientes consultar a un neurólogo o someterse a pruebas neurocognitivas de seis a ocho meses después del alta hospitalaria si sienten que todavía tienen problemas cognitivos, lentitud en el procesamiento de la información o poca atención (14).

Tratamiento y prevención

Aunque se han detectado receptores ACE2 en los ojos, no se ha llegado a informar de una afectación ocular asociada con la infección por SARS-CoV-2. Sin embargo, se recomienda tomar medidas preventivas de protección ocular cuando se entra en contacto con pacientes infectados con el SARS-CoV-2 para prevenir una posible propagación de la COVID-19 a través de una ruta ocular (10).

Aquellas personas que padecen de un riesgo vascular, tal como la obesidad, hipertensión o diabetes, tienden a sufrir más los efectos tras la infección por SARS-CoV-2 que cualquier persona sana. Por esta razón, es aconsejable que se mejore la calidad de vida de los ciudadanos, lo que aumentaría las probabilidades de una recuperación más favorable de los pacientes (4).

El estudio de Rejdak y Grieb (21) podría sugerir que los adamantanos ejercen un efecto de protección antiviral. Si esto se demuestra, la infección por SARS-CoV-2 y sus secuelas neurológicas clínicas se podrían frenar con el uso de estos medicamentos, que son unos fármacos comúnmente usados como tratamiento etiológico para mitigar los síntomas del párkinson y la disfunción cognitiva. La salida del ARN vírico de la célula por parte del canal de viroporina puede verse afectada por la estructura hidrocarbonada de los adamantanos. Esto podría interferir en la liberación del SARS-CoV-2 de las células infectadas. Por tanto, la administración de adamantanos se ha propuesto como un posible tratamiento contra la COVID-19 para aquellos pacientes más vulnerables.

Conclusiones

Los estudios incluidos en esta revisión sugieren que la cognición podría verse afectada como secuela de la COVID-19 en algunos pacientes, y que ello podría estar relacionado con el nivel inflamatorio producido por la infección. La proteína S viral del SARS-CoV-2 puede unirse al receptor de las células ACE2. Este receptor se encuentra presente en la superficie de numerosas células distribuidas por todo el cuerpo, lo que permite la entrada del virus a través de tres posibles vías: por canales del nervio olfatorio, por difusión transináptica o mediante células endoteliales vasculares o inmunitarias.

Debido a la infección por SARS-CoV-2 pueden producirse ciertos accidentes cerebrovasculares que son predisponentes al desarrollo de enfermedades neurodegenerativas, como la enfermedad de Parkinson o la enfermedad de Alzheimer, entre otras. A pesar de que no se han desarrollado tratamientos eficaces para tratar estas secuelas, sí que se han probado otros fármacos, como los adamantanos. No obstante, se recomienda ir al neurólogo de seis a ocho meses después de haber sufrido la enfermedad para hacer un seguimiento médico.

La principal limitación de este trabajo es que no hay una amplia bibliografía acerca de este tema. Por ello, es necesario que se planteen nuevos estudios en humanos en los que se haga un mayor seguimiento de los pacientes para conocer las características de las secuelas neurodegenerativas.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», especialmente a Pedro Redruello Guerrero por su dedicación y tutorización, así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo. Las figuras son de creación propia y han sido diseñadas gracias a BioRender (22).

Conflictos de interés

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10224):565-74.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13.

- Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. [citado 28 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.

- Fotuhi M, Mian A, Meysami S, Raji CA. Neurobiology of COVID-19. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2020;76(1):3-19.

- Huang L, Zhang X, Zhang X, Wei Z, Zhang L, Xu J, et al. Rapid asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 during the incubation period demonstrating strong infectivity in a cluster of youngsters aged 16-23 years outside Wuhan and characteristics of young patients with COVID-19: A prospective contact-tracing study. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e1-13.

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna M del C, R-delAmo JL, Fernández-García MÁ, Martínez-Diz S, Tahery-Mahmoud A, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory factors on admission associated with COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized patients: A retrospective observational study. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0235107.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna MDC, Martínez-Diz S, Fernández-García MÁ, Martín-Romero DT, Maldonado-Rodríguez F, Sánchez-Pérez MR, Martín-delosReyes LM, Martínez-Ruiz V, Lardelli-Claret P, Jiménez-Mejías E. Clinical Factors, Preventive Behaviours and Temporal Outcomes Associated with COVID-19 Infection in Health Professionals at a Spanish Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4305.

- Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, Davies NWS, Pollak TA, Tenorio EL, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875-82.

- Lai C-C, Ko W-C, Lee P-I, Jean S-S, Hsueh P-R. Extra-respiratory manifestations of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(2):106024.

- Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):767-83.

- Bridwell R, Long B, Gottlieb M. Neurologic complications of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1549.e3-1549.e7.

- Mcloughlin BC, Miles A, Webb TE, Knopp P, Eyres C, Fabbri A, et al. Functional and cognitive outcomes after COVID-19 delirium. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020; 11: 857–862.

- Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. Long-Term Respiratory and Neurological Sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26:e928996-1-e928996-10.

- Miners S, Kehoe PG, Love S. Cognitive impact of COVID-19: looking beyond the short term. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):170.

- Zhou H, Lu S, Chen J, Wei N, Wang D, Lyu H, et al. The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;129:98-102.

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):762-8.

- Mahalaxmi I, Kaavya J, Mohana Devi S, Balachandar V. COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: A possible associative approach towards neurodegenerative diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(2):763-770.

- Verkhratsky A, Li Q, Melino S, Melino G, Shi Y. Can COVID-19 pandemic boost the epidemic of neurodegenerative diseases? Biol Direct. 2020;15(1):28.

- Carod-Artal FJ. Complicaciones neurológicas por coronavirus y COVID-19. Rev Neurol 2020;70 (09):311-322.

- Rejdak K, Grieb P. Adamantanes might be protective from COVID-19 in patients with neurological diseases: multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42:102163.

- BioRender [Internet]. [citado 29 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://app.biorender.com/.

Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Neuronal Cells and its Possible Neurological Sequelae

This non-systematic review gathers data on neurological sequelae of COVID-19 patients aged 18 to 65 years. Scientific evidence shows that the main SARS-CoV-2 entry occurs through the ACE2 receptor, which is present in numerous cells of the organism. The virus penetrates the blood-brain barrier through vascular endothelial cells and immune cells; via the olfactory bulb and optic nerve channels; and across trans-synaptic transmission. In the central nervous system, the cytokine storm culminates in oxygen deprivation to neuronal cells. In the long term, this may lead to neurodegenerative diseases such as encephalopathy. Preliminary studies on treatment suggest a symptomatic approach proposing some pharmaceutical drugs such as adamantane. Therefore, some COVID-19 patients could experience cognitive sequelae, which could be related to the inflammation level produced by the infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, cognition, ACE2, spike protein, neuronal injury, neurological sequelae.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 agent (1,2) was identified in December 2019 at the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, Hubei (China). This virus caused atypical pneumonia of unknown origin and muscle aches, among other symptoms (2). Since then, the number of cases has increased significantly around the world (1). The WHO declared the situation to be a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (2). As of March 28, 2021, a total of 126,607,206 positive cases and 2,776,023 deaths were confirmed worldwide, according to data provided by Johns Hopkins University (3).

SARS-CoV-2 is a new betacoronavirus responsible for COVID-19 (4). The median incubation period is approximately two days, although it can vary from one to four days (5). The most common symptomatology produced by this microorganism includes fever, cough, fatigue, headache, anosmia, hyposmia, ageusia, dyspnea, and chest pain, among others (6–8). The second most common manifestation is altered mental status (9). Cerebrovascular injury and impaired consciousness developed within a mean period of 8 to 10 days after admission, while the rest of neurological manifestations occurred within a mean period of 1 to 2 days after admission. Neurological manifestations were more frequent in severe COVID-19 infected patients than in those with non-severe infection (10). The most common deficiencies are altered mental statuses such as delirium (13), severe cognitive, consciousness and personality disorder, and an alteration of the peripheral nervous system (9). Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 has been related to more severe symptoms. Examples include dysarthria, dystonia, seizures, confusion, and even death (11,12).

This non-systematic review aims to gather data provided by scientific evidence on the neurological sequelae of COVID-19 patients. In addition, this paper studies the possible mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into both cells and the organism through diffusion pathways to the central nervous system (CNS), and whether any treatment is currently available.

Methods

This review collected the studies found using the search equation ‘cognitive sequelae covid’ in the Medline database. The selection criteria were patients aged 18 to 65 years. Researchers have studied the cognitive sequelae of a post-COVID patient compared to the normal cognitive response in patients who have not been infected. This review has collected all studies published in 2020 related to this topic.

SARS-CoV-2 entry into human cells through the ACE2 receptor

Many chronic degenerative diseases could be the consequence of neuronal injury caused by COVID-19. Despite the potential direct or indirect effects of the disease, COVID-19 may permanently damage the CNS (14). One of the most vulnerable areas to ischemic injury by COVID-19 and of vital importance to cognitive function is cerebral white matter. The cumulative destructive effect of multifocal cerebral ischemia or hemorrhage together with the complications that arise after the disease, such as endothelial and blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction and upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines within the brain, may considerably increase the risk of chronic brain injury (15). In addition, a potential connection is established between cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (16). A higher report incidence of this connection was observed in elderly patients or those with COVID-19, or those with previous pathologies such as hypertension, diabetes or underlying cerebrovascular disease. However, young adults with COVID-19 also presented this incidence (15).

The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 together with the ACE2 helps the virus enter into the cell and allows it to infect it. The distribution of the expression of the ACE2 receptor in different locations in animal and human brain tissues is widely expressed in neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes throughout the brain (14) (Figure 1). Post-mortem studies have shown three major findings:

- ACE2 receptor, the main receptor of SARS-CoV-2, is widely expressed in brain microvascular endothelial cells, in pericytes throughout the body and in the brain (14,15).

- The spike protein can directly damage the integrity of the BBB to varying severity levels (14).

- The spike protein induces the inflammatory response of microvascular endothelial cells, which leads to BBB dysfunction (14).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the ACE2 receptor present in the central nervous system.

The virus binds to the ACE2 receptor in two different ways:

- Via the vascular endothelial cells. Vascular endothelial cells regulate BBB permeability through tight junctions. These junctions present an extensive expression of the ACE2 receptor, which provides the molecular mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 enters the BBB and invades the brain. The virus binds to the ACE2 receptor and enters the vascular endothelial cells by endocytosis and exocytosis, thus achieving cell-to-cell transmission. However, the virus does not replicate during transendothelial cell transfer. Viral replication delays until the virus reaches the target cells, such as neurons or glial cells, and binds to the ACE2 receptor before replication starts (14).

- Via the immune cells. Immune cells work as a bridge for SARS-CoV-2 to cross the BBB (17) using the Trojan horse mechanism. It requires two conditions: firstly, immune cells that express ACE2; and secondly, circumstances in which the virus does not replicate. Furthermore, the pathogen can enter macrophages cytoplasm by binding to the receptor on the surface using the ‘Trojan horse’ mechanism (14).

Mechanisms of entry into the organism

The respiratory tract is the main mechanism for SARS-CoV-2 to enter into the organism. This leads to pneumonia, which may be followed by fibrosis and chronic impairment of lung function. The infection by this pathogen affects the CNS and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) damaging both neurons and glial cells directly or indirectly. This may cause neuropathologies which could lead to long-term sequelae. Although virus transport via the olfactory bulb, associated with anosmia, is a potential route for neuroinvasion, the cerebral vasculature plays a more important role in entry of the virus into the CNS (15). The alteration of the BBB by SARS-CoV-2 and its entry into the brain support the formation of fatal microthrombi and even the occurrence of encephalitis (14). This association supports plausible hypotheses on the occurrence of long-term neurological sequelae. In addition, to cross the BBB, SARS-CoV-2 may enter the brain by:

– Optic nerve channel and olfactory bulb (18)

– Trans-synaptic transmission (19)

– Vascular endothelial cells (14)

The olfactory nerve contains both sustentacular cells, which maintain the integrity of the sense of smell, and stem cells, located in the olfactory epithelium. These cells express wild-type ACE2 and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), which could merge SARS-CoV-2 to the olfactory bulb and the sustentacular cells, followed by travel into the brain (14).

SARS-CoV-2 enters the central nervous system through two different routes: the olfactory route and the blood-brain barrier route. The virus can migrate into the CNS by endocytosis, due to its increased vascular permeability, which is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and an indirect transfer via the ‘Trojan horse’ mechanism. After binding to its membrane receptor, ACE2, the pathogen will be engulfed into neuronal cytosol and will connect with the angiotensin-converting enzyme in the cytosol. Both the virus and the ‘cytokine storm’ can destroy the myelin sheath, resulting in acute and chronic neuropathology (14) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the main mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into the central nervous system.

Optic nerve channel and olfactory bulb

The pro-inflammatory cytokines and the C-reactive protein (CRP) played a significant role in the development of SARS manifestation. SARS-CoV-2 particles are spread in the respiratory mucosa and infect other cells, inducing changes in peripheral immune cells. This elicits a cascade of immune responses, which results in a detrimental production of cytokines as this inflammation is directly linked to cognitive dysfunction (16).

Post-mortem studies on the cerebral pathology of COVID-19 patients and the use of an advanced 3D microfluidic model of the BBB identified that ACE2 receptor and the spike protein are expressed in brain microvascular cells. This protein can undermine the integrity of the BBB in different ways and induce inflammatory responses of microvascular cells, changing the function of the BBB. These findings support that the SARS-CoV-2 can alter BBB. Therefore, the virus can enter the brain and support the occurrence of neurological symptoms, the formation of fatal microthrombi, and even the occurrence of encephalitis. This supports the potential basis for the occurrence of long-term neurological sequelae (14).

When SARS-CoV-2 enters the CNS through the olfactory bulb, anosmia is triggered, causing neurodegenerative diseases due to loss of neurotransmitter induced by neuronal death. After the entry into the organism, viral replication may begin, releasing pro-inflammatory proteins. Triggered by oxidative mediators, loss of dopamine (DA) neurons or the aggregation of amyloid fibrils may result from the entry of the virus (18).

Trans-synaptic transmission

When SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor, it travels in an axonal manner to reach the CNS. Once reached the synaptic cleft, membrane coating-protected exocytosis, endocytosis, and vesicle transport lead to trans-synaptic transmission of the virus from one neuron to another and from neuron to satellite cells. Furthermore, the rapid intracellular axonal transport provides a structural basis for further virus transmission (14).

Effects on the nervous system

No matter what method of invasion SARS-CoV-2 uses, when it reaches its destination, it replicates and uses its viral mechanisms to cause cell death or functional impairment. Rapid viral replication, direct cell injury, immune system activation, and inflammatory mediators (including cytokines) cause COVID-19 severe symptoms and may explain SARS-CoV-2 infection long-term sequelae. The increase of inflammatory mediators, the so-called cytokine storm, may explain the multiple organ injury found in some COVID-19 patients and may also explain the effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the CNS. This pro-inflammatory cytokine storm increases vascular permeability. Furthermore, this may trigger abnormal blood coagulation and multiple organ failure. These cytokines may also increase microvascular permeability within the CNS, facilitating the virus entry through the BBB. The ‘cytokine storm’ may also promote the formation of thrombi by activating the coagulation system (14).

After SARS-CoV-2 infection, brain injury is caused due to autoimmunity. Furthermore, this autoimmune attack is known to cause encephalopathies, with psychotic or neurological symptoms. The brain is protected by the BBB, which makes it particularly vulnerable to an autoimmune attack. However, this is not particularly frequent among COVID-19 patients.

Pneumonia and ischemia are two of SARS-CoV-2 infection main consequences, and they lead to severe and prolonged hypoxia, which affects the brain causing acute negative effects in the most severe cases. These negative effects are associated with:

– Arterial oxygen reduction, which causes impairments of neuronal activity

– Neuronal oxidation caused by hypoxia

The inflammation accompanying COVID-19 increases levels of fibronectin, which facilitates clot formation. Moreover, a large number of COVID patients demonstrated these complications. Thus, Covid-19 patients are more likely to develop neurodegenerative diseases (19) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic illustration of the damage potentially produced by SARS-CoV-2 in the central nervous system.

Long-term sequelae

Coronaviruses may persist in CNS resident cells and can be cofactors associated with the development of long-term neurological expressions in genetically predisposed individuals. Several coronaviruses have been identified by serological tests in a wide range of neurological pathologies, such as Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and optic neuritis. Coronaviruses 229E, 293, and OC43 have been isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid and brain of patients with multiple sclerosis. A substantially higher prevalence of OC43 coronavirus has been reported in the brains of patients with multiple sclerosis in comparison to those in a control group. Furthermore, the immune response after the infection may provoke multiple sclerosis flare-ups in susceptible individuals (20).

Since some effects of SARS-CoV-2 may appear many months or years after the infection, it would be advisable to monitor patients who have suffered COVID-19. The cytokine storm caused by infection may lead to small eventual cerebrovascular accidents without provoking noticeable neurological deficiencies. Once a patient overcomes COVID-19, they may experience memory and attention problems or slow processing speed. Therefore, patients are advised to seek advice from a neurologist or undergo neurocognitive tests from six to eight months after medical discharge if they are still experiencing cognitive disorders, slow processing of information or attention deficit (14).

Treatment and prevention

Although ACE2 receptors have been found in the ocular organs, ocular damage associated with a SARS-CoV-2 infection has not been reported. However, it is advisable to take preventive eye protection measures when in contact withSARS-CoV-2 infected patients to prevent potential spreads of COVID-19 via an ocular route (10).

Individuals with vascular risk, such as obesity, hypertension or diabetes, are prone to suffer more from the sequelae of a SARS-CoV-2 infection in comparison to any healthy individual. It is therefore advisable to improve the quality of life in the general population, thereby increasing patients’ likelihood of a more favorable recovery (4).

The research by Rejdak and Grieb (21) may suggest that adamantane has an antiviral protective effect. If this is proven, SARS-CoV-2 infection and its clinical neurological sequelae could be slowed by the consumption of these drugs, which are commonly employed as a causal treatment to mitigate the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and cognitive dysfunction. Adamantane’s hydrocarbon structure may affect the viroporin channel, responsible for release of RNA-viruses (21). This could interfere with the release of SARS-CoV-2 from infected cells. Therefore, adamantane dispensation has been proposed as a potential treatment against COVID-19 for the most vulnerable patients.

Conclusion

The studies included in this review suggest that COVID-19 may affect cognition in some patients, and that this sequela could be related to the inflammation level produced by the infection. The SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein can bind to the ACE2 cell receptor, present on the surface of multiple cells throughout the body. Thus, the virus enters through three possible pathways: via the olfactory bulb, through trans-synaptic diffusion or by vascular, or immune endothelial cells.

Certain cerebrovascular accidents that are predisposing to the development of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease can emerge due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Scientists have not developed effective treatments for these sequelae yet, but they have tested other pharmaceutical drugs such as adamantanes. However, specialists recommend seeing a neurologist six to eight months after suffering the disease for medical follow-up.

The main limitation of this study is the limited bibliography on this subject. Therefore, it is necessary to propose new studies in which patients are more closely observed to learn the characteristics of neurodegenerative sequelae.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper appreciate the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, especially Pablo Redruello Guerrero for his dedication and mentorship, as well as the English translation team. The figures are of our creation and have been designed thanks to BioRender (22).

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10224):565-74.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13.

- Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 8]. Available at: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

- Fotuhi M, Mian A, Meysami S, Raji CA. Neurobiology of COVID-19. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2020;76(1):3-19.

- Huang L, Zhang X, Zhang X, Wei Z, Zhang L, Xu J, et al. Rapid asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 during the incubation period demonstrating strong infectivity in a cluster of youngsters aged 16-23 years outside Wuhan and characteristics of young patients with COVID-19: A prospective contact-tracing study. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e1-13.

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna M del C, R-delAmo JL, Fernández-García MÁ, Martínez-Diz S, Tahery-Mahmoud A, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory factors on admission associated with COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized patients: A retrospective observational study. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0235107.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna MDC, Martínez-Diz S, Fernández-García MÁ, Martín-Romero DT, Maldonado-Rodríguez F, Sánchez-Pérez MR, Martín-de los Reyes LM, Martínez-Ruiz V, Lardelli-Claret P, Jiménez-Mejías E. Clinical Factors, Preventive Behaviours and Temporal Outcomes Associated with COVID-19 Infection in Health Professionals at a Spanish Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4305.

- Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, Davies NWS, Pollak TA, Tenorio EL, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875-82.

- Lai C-C, Ko W-C, Lee P-I, Jean S-S, Hsueh P-R. Extra-respiratory manifestations of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(2):106024.

- Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):767-83.

- Bridwell R, Long B, Gottlieb M. Neurologic complications of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1549.e3-1549.e7.

- Mcloughlin BC, Miles A, Webb TE, Knopp P, Eyres C, Fabbri A, et al. Functional and cognitive outcomes after COVID-19 delirium. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020; 11: 857–862

- Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. Long-Term Respiratory and Neurological Sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26:e928996-1-e928996-10.

- Miners S, Kehoe PG, Love S. Cognitive impact of COVID-19: looking beyond the short term. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):170.

- Zhou H, Lu S, Chen J, Wei N, Wang D, Lyu H, et al. The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;129:98-102.

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):762-8.

- Mahalaxmi I, Kaavya J, Mohana Devi S, Balachandar V. COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: A possible associative approach towards neurodegenerative diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(2):763-770.

- Verkhratsky A, Li Q, Melino S, Melino G, Shi Y. Can COVID-19 pandemic boost the epidemic of neurodegenerative diseases? Biol Direct. 2020;15(1):28.

- Carod-Artal FJ. Complicaciones neurológicas por coronavirus y COVID-19. Rev Neurol 2020;70 (09):311-322

- Rejdak K, Grieb P. Adamantanes might be protective from COVID-19 in patients with neurological diseases: multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42:102163.

- BioRender [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 29]. Available at: https://app.biorender.com/

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Guiomar-Córdova A, Bustos-Romano M, Sánchez-Correa D. Mecanismos de entrada del SARS-CoV-2 a las células neuronales y sus posibles secuelas neurológicas. AMU. 2021; 3(1):112-123