Adela Serrano-Herrera ¹ , Cristina Rodríguez-Martínez ¹ , Paula Domingo-López ¹ , Alberto Girona-Torres ¹ , Pablo Sola- Montijano1, Javier Domingo-López ¹

1 Estudiante del Grado en Medicina de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

TRANSLATED BY:

María García-Navarro ² , Natalia Morata-Garrido ² , Gavin Darroch ² , Jesús Sánchez-Rodríguez ² , Begoña Martín- Vázquez ² , Carmen Salmerón-Borja ³

2 Student of the MA in Professional Translation at the University of Granada (UGR)

3 Student of the BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (UGR)

Resumen

El cáncer de próstata supone un tercio de los nuevos casos de cáncer al año, convirtiéndose en el más frecuente en hombres. Datos recientes sugieren que pacientes diabéticos que toman metformina, el medicamento más empleado en la Diabetes tipo II, tienen una menor incidencia de padecer ciertos cánceres, como el de próstata. Un gran número de estudios han examinado el potencial antineoplásico de la metformina, aunque aún no se comprende del todo y los datos obtenidos son ambiguos. Esta revisión resume la información referente a los efectos de la metformina sobre las células del cáncer de próstata, destacando algunos de los mecanismos de acción a través de los cuales puede actuar dicho fármaco. También analiza algunas discordancias referentes a los efectos de la metformina sobre pacientes con distintos perfiles metabólicos y farmacológicos. Tras comparar los datos, sugerimos que la metformina podría tener un importante papel en el futuro para el manejo del cáncer de próstata, tanto en monoterapia, como en combinación; aunque a día de hoy sigue siendo necesario realizar ensayos clínicos más sólidos para confirmar su eficacia.

Palabras clave: metformina, cáncer, próstata, diabetes, AMPK, terapia de deprivación androgénica (TDA).

Keywords: metformin, cancer, prostate, diabetes, AMPK, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

1. INTRODUCCIÓN

El cáncer de próstata (CaP) es el más cáncer más frecuente entre los hombres y la segunda causa de muerte oncológica de los mismos (1). Debido a la elevada prevalencia de esta patología, además de nuevas moléculas, se están empleando fármacos con otras indicaciones para su tratamiento.

La metformina es un medicamento comúnmente utilizado en el tratamiento para la Diabetes Mellitus tipo II (DMII). Aunque sus mecanismos no están concretados con certeza, sus propiedades antineoplásicas, antiinflamatorias y metabólicas podrían ejercer un efecto favorable sobre el pronóstico y evolución del CaP.

Sin embargo, al adentrarse en el estudio de los mecanismos y efectos de la metformina sobre el CaP, encontramos puntos de controversia entre las diferentes fuentes de información.

Nuestra intención es exponer los distintos aspectos de la evolución y tratamiento del CaP sobre los que la metformina parece actuar favorable o desfavorablemente. Nos enfocamos tanto en la aplicación y efectos observables de la metformina en la práctica clínica como en las distintas vías químicas y metabólicas sobre las que se cree que ejerce su efecto.

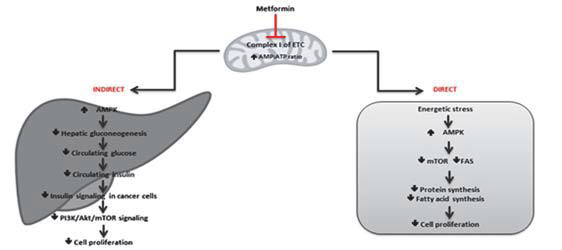

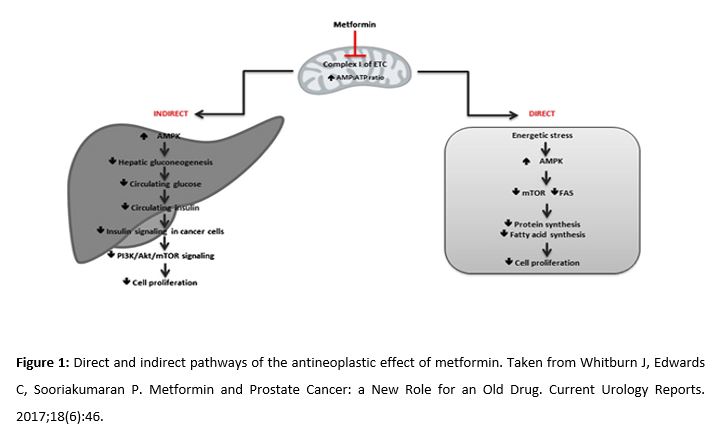

2. VÍA DE LA METFORMINA

En relación a su efecto en el CaP, se describen dos vías de acción (Fig. 1): una directa sobre las células tumorales (inhibe la cadena transportadora de electrones) (2) y otra indirecta, a través de la disminución de los niveles de insulina y otros factores proliferativos (como los receptores androgénicos, fundamentales en el CaP). Además, la metformina bloquea los mecanismos de obtención de energía de las células tumorales: la gluconeogénesis hepática y la glucólisis (esta última si se combina con 2- desoxiglucosa) (3). Aunque la acción indirecta tiene cierto interés por el carácter órgano-específico de la metmorfina, los mecanismos no están totalmente establecidos, por lo que nos centraremos en desarrollar la vía directa de acción sobre las células tumorales.

Mecanismos dependientes de adenosín monofosfato kinasa

La metformina inhibe directamente la cadena respiratoria mitocondrial. Esto reduce los niveles de adenosín trifosfato (ATP) y aumenta la proporción AMP/ATP, lo que supone la activación de la adenosín monofosfato kinasa (AMPK) y la reducción de la producción de glucosa (4). Bajo estas condiciones de estrés, la kinasa hepática B1 (LKB1), conocida por su papel supresor de tumores, activará a la AMPK y reducirá el complejo de la diana de rapamicina en células de mamífero (mTOR) (5). Al inhibir mTor, se actúa sobre la vía de señalización Pl3k/AKT/mTOR, asociada a una proliferación celular anormal, inhibición de la apoptosis y carcinogénesis. Por otro lado, al activar la vía AMPK, aumenta la producción del factor de transcripción Forkhead box O3 (FOXO3). La inactivación de este gen está implicada en la progresión del cáncer de próstata, haciendo de su activación a través de la metformina una opción terapéutica (6).

Mecanismos independientes de AMP K

La activación de AMPK es el principal mecanismo antineoplásico de la metformina, pero se han descrito otras vías. Un ejemplo lo reportaron Sarah et al. que afirmaron que Redd1 y ciclina D1 median los efectos antiproliferativos de la metformina en las células del CaP (7). Este efecto también lo induce la metformina al activar la vía LKB1 (reduce su ARN mensajero) y disminuir los niveles de c-MYC (8,9,10). Esta acción es fundamental puesto que los andrógenos inducen una regulación al alza de los receptores del factor de crecimiento insulínico tipo 1 (IGF-1R) y de la insulina (IR), ya de por sí sobreexpresados en las células tumorales del CaP. Cuando estos receptores se activan, la vía mTOR estimula la proliferación y la invasión celular. Finalmente, otros estudios subrayan que la metformina también bloquea los ejes COX2 /PGE2/STAT2/transición epitelio-mesénquima (TEM) y el factor Fox M1, ambos con un papel central en la regulación del ciclo celular, angiogénesis, invasión, metástasis y TEM, que también se verá reducida por la modulación de los microARNs (11,12).

Por tanto, la metformina actúa sobre una gran variedad de dianas moleculares y miles de vías de transducción. A esto se suma la falta de datos sobre efectos relevantes en las células benignas, sugiriendo que su acción pro-apoptótica se limite a las malignas (8). La actividad antineoplásica de la metformina podría explicar la disminución en la incidencia, in vivo e in vitro, de distintos tipos de cáncer (colon, mama o páncreas) si se emplea como tratamiento (13). Se determinó una disminución de la proliferación tumoral in vitro en ratones, sin embargo, las dosis empleadas en este tipo de estudios son entre 100 y 300 veces mayores a las empleadas en los tratamientos antidiabéticos estándar (14). Por otro lado, en un estudio se evidenció una disminución de Ki 67 en el 30% de los pacientes oncológicos (tanto diabéticos como no) antes de someterse a cirugía, pero no hubo una disminución significativa del PSA (marcador del CaP). Por contraparte, la metodología de este trabajo fue cuestionada (15). Por último, aunque in vitro la metformina actúa sobre los osteoblastos y las células madre tumorales, sus efectos sobre las metástasis óseas no se han demostrado (10).

3. Efectos de la metformina en diversos grupos de pacientes

Pacientes diabéticos y obesos

La diabetes es por sí misma un factor de riesgo de padecer cáncer (16); sin embargo, se ha determinado un descenso de su aparición en diabéticos que tomaban metformina frente a los que no (7,3% vs 11,6%). Este efecto no se ha observado con otros fármacos antidiabéticos como las sulfonilureas (17). Aunque se observó también una menor mortalidad asociada al uso de metformina, se evidencian discrepancias en los resultados, probablemente asociadas a diferencias en las características de los pacientes (18). En contraposición, otros estudios niegan el papel protector de la metformina en el CaP (19). Del mismo modo, varios estudios han demostrado que, empleada como tratamiento en los estadios iniciales y finales del cáncer, la metformina carece de efectos (20-23). De esta conclusión, algunos investigadores destacan la ausencia de estudios en otras fases y en pacientes con CaP (15).

En oposición a los trabajos anteriormente expuestos, algunos autores sugirieron que la Diabetes Mellitus tipo II y la obesidad podrían tener un cierto efecto protector en el caso específico del CaP, más incluso que el de la propia metformina (que por otro lado impediría este efecto). Estas patologías reducen los niveles de andrógenos (testosterona y dihidrotestosterona) y los factores genéticos que estimulan el crecimiento inicial de las células tumorales (24). Además, postularon la ausencia de efectos beneficiosos significativos en el uso de metformina para la prevención o tratamiento del CaP en la población general. Pese a la falta de datos concluyentes, la metformina es el fármaco de elección en pacientes oncológicos con DMII (25).

La gran cantidad de factores de confusión (los estudios son retrospectivos y los trabajos en no diabéticos escasos) impiden dilucidar si realmente es el control de la diabetes y no la metformina en sí la que reduce el riesgo de desarrollar un cáncer. Del mismo modo, son necesarios estudios más extensos para valorar los efectos a largo plazo del fármaco.

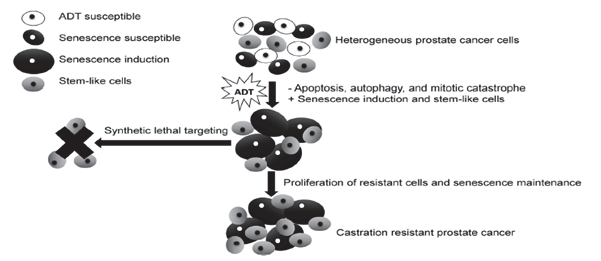

Pacientes en terapia de deprivación androgénica

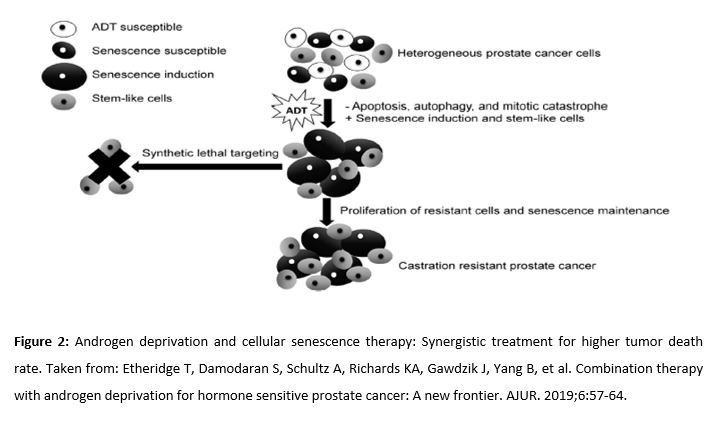

La terapia de deprivación androgénica (TDA), normalmente realizada con la administración de hormona liberadora de gonadotrofina (GnRH), es el tratamiento habitual en el cáncer de próstata localmente avanzado, recurrente o metastásico. La TDA induce la apoptosis de un 2-3% de las células tumorales, pero también activa otros mecanismos como la autofagia (por aumento de actividad de AMPK), la necrosis o la quiescencia. Las células quiescentes todavía son viables y pueden volver a entrar al ciclo celular (Fig. 2), de manera que, aunque inicialmente haya una alta respuesta a la TDA, estos cánceres acaban volviéndose resistentes a la terapia (25, 26). Algunos estudios clínicos sugieren que la TDA induce cambios en las células tumorales, haciéndolas más susceptibles al efecto de otros tratamientos sinérgicos, como ocurre con el decetaxel (mejora la supervivencia). Por este motivo, se plantea estudios de terapia sinérgica con metmorfina dadas sus propiedades antineoplásicas, antiinflamatorias y metabólicas (25,27,28).

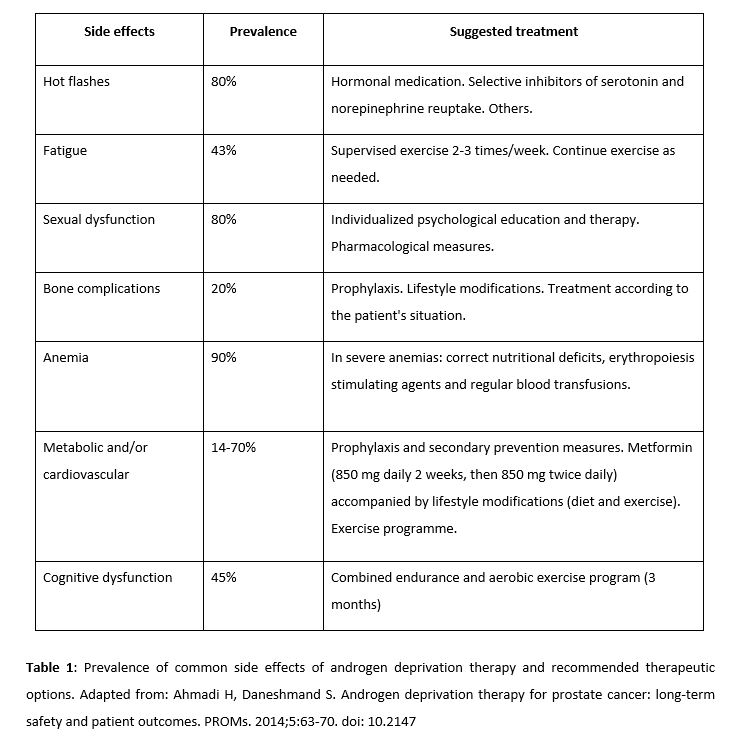

La metformina en los efectos adversos de la TDA

La TDA produce diversos efectos adversos (tabla 1) como fatiga, flushing vasomotor, disfunción sexual, complicaciones óseas (osteoporosis), anemia o disfunción cognitiva. Entre ellos se remarcan los efectos metabólicos y cardiovasculares (obesidad, dislipemia, aumento de la resistencia a la insulina y diabetes), ya que podrían evitarse con la toma de metformina (28, 29). Richard KA et al., en un estudio retrospectivo con una muestra de 87.344 veteranos, demostró que la metformina combinada con TDA mejoraba la supervivencia global en diabéticos tipo II, reducía el riesgo de complicaciones relacionadas con el esqueleto y la necesidad de usar radioterapia o cirugía debido a estas complicaciones (30). Por otro lado, en el estudio de Nobes et al. en pacientes no diabéticos se evidenció que el cambio en el estilo de vida (dieta y ejercicio) combinado con la metformina ayuda a reducir peso, índice de masa corporal, presión sistólica y el riesgo a padecer diabetes en el contexto del tratamiento con TDA comparado con el control. Sin embargo, en este estudio no se hallaron diferencias en los marcadores de resistencia a la insulina, no se intentó demostrar el aumento de la supervivencia global ni se establece si estos cambios se debían a la metformina o a los cambios en el estilo de vida (31). La evidencia disponible apunta a que combinar TDA con metformina podría ser una buena opción para mejorar la supervivencia del paciente, sea por su efecto sobre las células tumorales o por sus beneficios contra los efectos adversos de la TDA.

Pacientes con TDA y tumores hormonalmente resistentes

El 10%-20% de los pacientes con CaP se vuelven resistentes a la TDA, lo que se denomina CaP resistente a la castración de andrógenos (CRPC) (32). Esta variedad está relacionada con trastornos genéticos como mutación o amplificación del gen receptor androgénico (AR) o sobreexpresión de los genes responsables del paso de andrógenos a dehidrotestosterona (33). En estos casos, se recomienda administrar metformina por su perfil farmacológico seguro, por establecer una sinergia con otros tratamientos empleados (inhibidores PI3K/Akt y los antiandrógenos) y por presentar un efecto terapéutico contra los efectos secundarios de los mismos (náuseas, vómitos, diarrea e hiperglucemia (34). Aunque tanto la metformina como la combinación de antiandrógenos e inhibidores de PI3K producen diarrea por separado, la asociación de estos fármacos no incrementa su prevalencia frente a la monoterapia (35).

Dado que se ha observado que una desregulación de la vía PI3K/Akt en un 42% del CaP localizado y en un 100% en fases avanzadas (36), esta vía se ha convertido en la diana de los nuevos ensayos clínicos para el CRPC (37). Se están empleando inhibidores de los 3 componentes principales de la vía: PI3K, Akt y mTOR, siendo los inhibidores de los dos primeros más eficaces. Sin embargo, estos fármacos no son efectivos en monoterapia y se emplean con otros tratamientos, como el doble bloqueo PI3K/Akt-andrógenos (38). La utilización de antiandrógenos en principio no tiene sentido en los CRPC, sin embargo, se ha visto que esta resistencia es reversible debido a la activación de Akt (PKB). Por ello, la inhibición de la vía de la Akt restablece la respuesta a andrógenos, mayoritariamente en células con mutación en PTEN (39). Este hecho se confirmó con modelos celulares experimentales, no obstante, los resultados de los ensayos clínicos son variables por la diferencia en el bloqueo provocado por ciertos inhibidores y la ineficacia de algunos antiandrógenos. Estos ensayos sugieren que la combinación óptima sería un inhibidor de PI3K o Akt junto con un antiandrógeno de nueva generación, cuyo efecto terapéutico podría mejorarse con el uso de metformina (40-42).

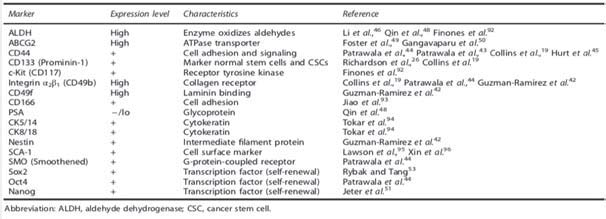

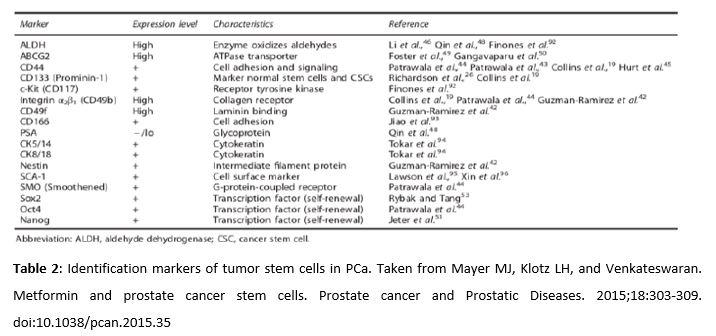

Metformina sobre las células madre tumorales quiescentes.

Entre las células tumorales resistentes al TDA, destacan las células madre tumorales que quedan en estado quiescente tras la terapia. Este reservorio de células madre, identificables mediante distintos marcadores recogidos en la Tabla 2, pueden volver a proliferar en cualquier momento, produciendo una recurrencia del cáncer. Hay evidencias de que la metformina puede actuar selectivamente en las células madre para inhibir la proliferación tumoral y sensibilizarlas para mejorar el efecto de otros tratamientos (43-44). Es importante destacar que para que la metformina produzca correctamente sus efectos antineoplásicos, es necesario que la célula exprese el transportador de membrana OCT1. Este transportador permite que el potencial de membrana mitocondrial atraiga a la metformina al interior de las mitocondrias, alcanzando así grandes concentraciones. No obstante, la expresión de OCT1 en células madre tumorales prostáticas no ha sido demostrada todavía (45).

Discusión sobre los efectos antineoplásicos de la metformina

Aunque se determinó una disminución de la proliferación tumoral in vitro en ratones, las dosis administradas en este tipo de estudios eran entre 100 y 300 veces mayores a las empleadas en tratamientos antidiabéticos estándar (14).

4. Conclusión

Aunque la evidencia señale el efecto beneficioso de la metformina en el cáncer de próstata, todavía quedan muchos aspectos que aclarar mediante estudios más sólidos. Por ejemplo, si sus efectos pueden beneficiar a todos los pacientes o tipos de tumores, si la dosis antidiabética es la antitumoral o si presenta efectos en la prevención, en el tratamiento o en ambos. Además, tampoco se han evaluado sus posibles efectos adversos.

La metformina es una sustancia con efectos antitumorales in vitro, sin embargo, su potencial real como agente antineoplásico todavía no ha podido determinarse. La gran cantidad de factores de confusión de los estudios retrospectivos y la escasez de estudios en no diabéticos (no se ha demostrado el efecto anticancerígeno de la metformina en este grupo), nos hacen cuestionarnos si realmente es el control de la diabetes y no la metformina en sí la que reduce el riesgo de desarrollar un cáncer y aumentar la supervivencia de los pacientes oncológicos, especialmente si reciben TDA. Del mismo modo, son necesarios estudios más extensos para valorar los efectos a largo plazo del fármaco.

Estas primeras evidencias sobre el potencial efecto beneficioso de la metformina, especialmente si se utiliza como adyuvante, en una patología tan prevalente como el CaP justifican la realización de más ensayos sobre esta temática. Estos estudios deberán seguir una metodología crítica y estricta para determinar si los efectos de metformina tendrán una repercusión clínica real.

5. Conflicto de intereses

Los autores niegan la existencia de cualquier conflicto de interés.

6. Referencias

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29.

- Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J. 2000;348(3):607–14.

- Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):251–62.

- Miller RA, Birnbaum MJ. An energetic tale of AMPK-independent effects of metformin. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2267–70.

- Zingales V, Distefano A, Raffaele M, Zanghi A, Barbagallo I, Vanella L. Metformin: A Bridge between Diabetes and Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017; 7:243.Whitburn J, Edwards CM, Sooriakumaran P.

- Das TP, Suman S, Alatassi H, Ankem MK, Damodaran C. Inhibition of AKT promotes FOXO3a- dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7:e2111.

- Wang Y, Yao B, Wang Y, Zhang M, Fu S, Gao H, et al. Increased FoxM1 expression is a target for metformin in the suppression of EMT in prostate cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2014; 33(6):1514–22.

- Akinyeke T, Matsumura S, Wang X, Wu Y, Schalfer ED, Saxena A, et al. Metformin targets c-MYC oncogene to prevent prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013; 34(12):2823–32.

- Demir U, Koehler A, Schneider R, Schweiger S, Klocker H. Metformin anti-tumor efect via disruption of the MID1 translational regulator complex and AR downregulation in prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:52.

- Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Bolanowski M, Kręcicki T, Zatoński T. Diabetes and cancer: a review of current knowledge. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2016;124:263–75.

- Qin G, Xu F, Qin T, Zheng Q, Shi D, Xia W, et al. Palbociclib inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in breast cancer via c-Jun/ COX-2 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2015; 6(39):41794–808.

- Hitron A, Adams V, Talbert J, Steinke D. The influence of antidiabetic medications on the development and progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012; 36(4):e243–50.

- Tseng CH. Diabetes, metformin use, and colon cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012; 167(3):409–16.

- Ben Sahra I, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an anti-tumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27(25):3576–86.

- Whitburn J, Edwards C, Sooriakumaran P. Metformin and Prostate Cancer: a New Role for an Old Drug. Current Urology Reports. 2017;18(6):46.

- Joshua AM, et al. A pilot ‘window of opportunity’ neoadjuvant study of metformin in localised prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17(3):252–8.

- Bowker SL, et al. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):254–8.

- Libby G, et al. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1620–5.

- Bo S, Ciccone G, Rosato R, Villois P, Appendino G, Ghigo E, et al. Cancer mortality reduction and metformin: a retrospective cohort study in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012; 14(1):23–9.

- Wu GF, Zhang XL, Luo ZG, Yan JJ, Pan SH, Ying XR, et al. Metformin therapy and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015; 8(8):13089–98.

- Yin M, Zhou J, Gorak EJ, Quddus F. Metformin is associated with survival benefit in cancer patients with concurrent type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2013;18:1248–55.

- Kordes S, et al. Metformin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):839–47.

- Sayed R, et al. Metformin addition to chemotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: an open label randomized controlled study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6621–6.

- Reni M, et al. (Ir)relevance of metformin treatment in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: an open-label, randomized phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(5):1076–85.

- Rastmanesh R, Hejazi J, Marotta F, Hara N. Type 2 diabetes: a protective factor for prostate cancer? An overview of proposed mechanisms. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12:143–8.

- Litwin MS, Tang H. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2017; 317(24): 2532-2542. doi:10.1001

- Tseng CH. Metformin significantly reduces incident prostate cancer risk in Taiwanese men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2831–7.

- Etheridge T, Damodaran S, Schultz A, Richards KA, Gawdzik J, Yang B, et al. Combination therapy with androgen deprivation for hormone sensitive prostate cancer: A new frontier. AJUR. 2019;6:57-64.

- Ojeda S, Lloret M, Naranjo A, Déniz F, Chesa N, Domínguez C, et al. Deprivación androgénica en cáncer de próstata y riesgo de fractura a largo plazo. Actas Urol Esp. 2017; 41(8): 491-496.

- Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, Oudard S, Priou F, Esterni B, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in noncastrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149-58.

- Gamat M, McNeel DG. Androgen deprivation and immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. ERC. 2017;24:297-310. doi:10.1530.

- Ahmadi H, Daneshmand S. Angrogen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: long-term safety and patient outcomes. PROMs. 2014;5:63-70. doi: 10.2147.

- Richards KA, Liou JI, Cryns VL, Downs TM, Abel EJ, Jarrard DF. Metformin use is associated with improved survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol. 2018;200:1256-63. doi: 10.1016.

- Nobes JP, Langley SE, Klopper T, et al. A prospective, randomized pilot study evaluating the effects of metformin and lifestyle intervention on patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy. BJU Int. 2012;109:1495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.

- Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010; 18:11-22.

- Kirby M, Hirst C, Crawford ED. Characterising the castration-resistant prostate cancer population: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011; 65:1180-1192.

- Edlind MP, Hsieh AC. PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J Androl. 2014; 16(3):378-386.

- Delma MI. Three May Be Better Than Two: A Proposal for Metformin Addition to PI3K/AKt Inhibitor-antiandrogen Combination in Castration-resistan Prostate Cancer. Cureus. 2018; 10(10):e3403.

- Rothermundt C, Hayoz S, Templeton AJ, et al. Metformin in chemotherapy-naive castration resistant prostate cancer: a multicenter phase 2 trial (SAKK 08/09). Eur Urol. 2014; 66:468- 474.

- Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013; 20:R83-R99.

- Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011; 19:575-586.

- Khan KH, Wong M, Rihawi K, Bodla S, Morganstein D, Banerji U, Molife LR. Hyperglycemia and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) inhibitors in phase I trials: incidence, predictive factors, and management. Oncologist. 2016, 21: 855-860.

- Zong Y, Goldstein AS. Adaptation or selection-mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013; 10: 90–98.

- Saini N, Yang X. Metformin as an anti-cancer agent: actions and mechanisms targeting cancer stem cells. ABBS. 2017; 50: 133-143. doi: 10.1093

- Pollak M. Potential applications for biguanides in oncology. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3693–3700.

The Frontiers of Metformin: From Diabetes to Prostate Cancer

Abstract

Prostate cancer accounts for one-third of new cases of cancer per year, and is now the most frequent type of cancer in men. Recent data suggest that diabetic patients who take metformin, the drug most commonly used in type 2 diabetes, have a lower incidence of certain cancers, such as prostate cancer. Numerous studies have examined the antineoplastic potential of metformin, although its mechanisms are not yet fully understood and the data obtained are ambiguous. This review summarizes the information regarding the effects of metformin on prostate cancer cells, highlighting some of the mechanisms of action through which this drug may act. It also analyzes some conflicting findings regarding the effects of metformin on

patients with different metabolic and pharmacological profiles. After comparing the data, we suggest that metformin could play an important role in the management of prostate cancer in the future, both in monotherapy and combined therapy. At this stage, however, it is still necessary to carry out more effective/ extensive clinical trials to confirm its efficacy.

Keywords: metformin, cancer, prostate, diabetes, AMPK, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequent cancer among men and the second leading cause of oncological death (1). Due to its high prevalence, in addition to new molecules, some drugs indicated for other pathologies are being used to treat it.

Metformin is a type of drug commonly used in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Although its mechanisms are not yet fully understood, its antineoplastic, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic properties could have beneficial effects on PCa prognosis and evolution.

However, there is disagreement between the different sources of information in relation to the mechanisms and effects of metformin on PCa.

The aim of this article is to present the different aspects of PCa evolution and treatment in which metformin might have beneficial or negative effects. This article is focused on the application and observable effects of metformin in clinical practice, as well as on the different chemical and metabolic pathways that metformin is believed to affect.

- Metformin action mechanisms

In relation to its effect on PCa, two mechanisms of action are described (Fig. 1). One of them has a direct effect on tumor cells (by inhibiting the electron transport chain) (2), and the other is indirect, reducing levels of insulin and other growth factors (such as androgenic receptors, which are fundamental in PCa). In addition, metformin blocks the mechanisms through which tumor cells obtain energy: hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycolysis (the latter if combined with 2-deoxyglucose) (3). Although the indirect action is interesting considering the organ-specific character of metformin, the mechanisms are not fully established. Thus, we will focus on developing the direct mechanism of action on tumor cells.

2.1. Mechanisms dependent on adenosine monophosphate kinase

Metformin directly inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain. This reduces the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels and increases the AMP/ATP ratio, which involves the activation of adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) and reduces glucose production (4). Under these stressful conditions, liver kinase B1 (LKB1), known for its tumor suppressant role, will activate AMPK and reduce the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (5). Inhibiting mTOR activates the Pl3k/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, associated with abnormal cell proliferation, apoptosis inhibition, and carcinogenesis. On the other hand, activating the AMPK pathway increases the production of the transcription factor Forkhead box O3 (FOXO3). The inactivation of this gene is involved in the progression of PCa, making its activation through metformin a therapeutic option (6).

2.2. Mechanisms independent of AMPK

Activation of AMPK is the main antineoplastic mechanism of metformin, but other pathways have been described. For example, Sarah et al. stated that Redd1 and cyclin D1 mediate the antiproliferative effects of metformin on PCa cells (7). This effect is also induced by metformin when the LKB1 pathway is active reducing its messenger RNA, and decreasing c-MYC levels (8,9,10). This action is fundamental, since androgens induce an increased regulation of insulin growth factor type 1 receptors (IGF-1R) and insulin receptors (IR), which are already overexpressed in PCa tumor cells. When these receptors are activated, the mTOR pathway stimulates cell proliferation and invasion. Finally, other research highlights that metformin also blocks the COX2/PGE2/STAT2/epithelium-mesenchymal transition (EMT) axis and the Fox M1 factor, both of which play a central role in cell cycle regulation, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and EMT; the last of which will also be reduced by the modulation of microRNAs (11,12).

Therefore, metformin acts on a wide variety of molecular targets and thousands of transduction pathways. There is also a lack of data on significant effects on benign cells, which suggests that its pro-apoptotic action is specific to malignant cells (8). The antineoplastic activity of metformin could explain the decrease in the incidence of different types of cancer (colon, breast or pancreas), in vivo and in vitro, when metformin is used as a treatment (13). A decrease in tumor proliferation was determined in vitro in mice, however, the doses used in this type of studies are between 100 and 300 times higher than those used in standard antidiabetic treatments (14). On the other hand, another study showed a decrease in Ki 67 in 30% of cancer patients (both diabetic and non-diabetic) before undergoing surgery, but reported no significant decrease in PSA (PCa marker). Nevertheless, the methodology of this work has been questioned (15). Finally, although metformin has an effect on osteoblasts and tumor stem cells in vitro, its effects on bone metastases have not been demonstrated (10).

- Effects of metformin in various groups of patients

3.1. Diabetic and obese patients

Diabetes is a risk factor for cancer (16). However, a decrease in cancer occurrence has been observed in diabetic patients taking metformin, as compared to those not taking it (7.3% vs. 11.6%). This effect has not been observed with other antidiabetic drugs, such as sulfonylureas (17). Although the use of metformin has also been associated with a lower mortality rate associated with the use of metformin has also been reported; however, discrepancies have been documented in the results, probably due to significant differences the characteristics of patients (18). In contrast, other research denies the protective role of metformin in PCa (19). Similarly, several studies have shown that metformin, used as a treatment in the early and late stages of cancer, has no effect (20-23). In response to this conclusion, some researchers highlight the lack of studies involving other stages of cancer and in patients with PCa (15).

Contrary to the works previously mentioned, some authors have suggested that type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity could have a certain protective effect in the specific case of PCa; an effect even greater than that of metformin (which, in contrast, would inhibit this effect). These pathologies reduce the levels of androgens (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone) and of the genetic factors that stimulate the initial growth of tumor cells (24). In addition, they noted that the use of metformin for the prevention or treatment of PCa among the general population had no significant benefits. Despite the lack of conclusive data, metformin is the drug of choice in cancer patients with T2DM (25). There are many confounding factors because studies are retrospective and there are few works on non-diabetics. Thus, it is impossible to determine whether it is really diabetes control, and not metformin itself, that reduces the risk of developing cancer. Similarly, more extensive research is needed in order to assess the long-term effects of this drug.

3.2. Patients in androgen deprivation therapy

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), usually performed with the administration of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), is the usual treatment for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic PCa. ADT induces apoptosis of 2-3% of tumor cells. However, it also activates other mechanisms such as autophagy (due to increased activity of AMPK), necrosis, or quiescence. Quiescent cells are still viable and can return to the cell cycle (Fig. 2). As a result, although initially there is a high response to ADT, these cancers eventually become resistant to therapy (25, 26). Some clinical studies suggest that ADT induces changes in tumor cells, making them more susceptible to the effect of other synergistic treatments, such as docetaxel (improves survival). For this reason, several studies explore combined therapy with metformin, given its metabolic, anti-inflammatory and antineoplastic properties (25,27,28).

3.3. Use of metformin to treat the adverse effects of ADT

ADT can cause a range of adverse side effects (Table 1) such as fatigue, vasomotor flushing, loss of libido and impotence, bone-related complications (osteoporosis), anemia, and cognitive dysfunction. Notably, some metabolic and cardiovascular effects (obesity, dyslipidemia, increase in resistance to insulin, and diabetes) could potentially be avoided by taking metformin (28, 29). In a retrospective study of 87,344 elderly patients, Richard KA et al. demonstrated that metformin combined with ADT improved the overall survival rate in patients with type 2 diabetes, reduced the risk of skeletal complications and the need for radiotherapy or surgery due to these conditions (30). Conversely, Nobes et al. (34) found that a change in lifestyle (diet and exercise) in non-diabetic patients, combined with metformin, helped to reduce weight, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, and the risk of contracting diabetes (combined with ADT and compared to the control group). However, in that study, no differences were found in markers of insulin resistance. The study did not attempt to show the increase in overall survival rate, and it is not clear whether these changes were the result of using metformin or the changes in lifestyle (31). The available evidence points to the combination of ADT with metformin being a potentially effective option for improving the survival rate of patients, either through its effects on tumor cells or its benefits against the adverse effects of ADT.

3.4. Patients in ADT with hormone-resistant tumors

Between 10-20% of patients with PCa become resistant to ADT. This is called castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) (32). This type of cancer is linked to genetic disorders such as mutation or replication of the androgen receptor (AR) gene, or overexpression of the genes responsible for the conversion of androgens into dihydrotestosterone (33). In these cases, administering metformin is recommended due to its safe pharmacological profile, its established synergy with other treatments (PI3K/Akt inhibitors and antiandrogens), and its therapeutic action against the side effects of these treatments (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperglycemia) (34). Although both metformin and the combination of antiandrogens and PI3K inhibitors each cause diarrhea, the interaction of these drugs does not increase the occurrence of diarrhea compared to monotherapy (35).

Given the observed disruption to the PI3K/Akt pathway (by 42% in localized PCa cases and by 100% in advanced stages) (36), this mechanism has become the target of new clinical trials involving CRPC (37). Inhibitors are being used to disrupt the three main components of the mechanism: PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. The inhibitors of PI3K and Akt are the most effective. However, these drugs are not effective in monotherapy and must be used together with other treatments, such as the PI3K/Akt-androgen dual blockade (38). The use of antiandrogens in CRPC cases is senseless in principle; however, it has been noted that this resistance is reversible due to the activation of Akt (PKB). Therefore, the inhibition of the Akt pathway restores the responsiveness to androgens, predominantly in PTEN mutant cells (39). Cellular experimental models confirmed this fact. Nevertheless, the results of clinical trials vary due to the difference in the blockade produced by certain inhibitors and the inefficiency of some antiandrogens. These trials suggest that the optimal combination would be a PI3K or Akt inhibitor combined with a new-generation antiandrogen, whose therapeutic effect could be improved with the use of metformin (40-42).

3.5. Effects of metformin on quiescent cancer stem cells

Amongst cancer cells resistant to ADT, there are cancer stem cells which remain in quiescent state after therapy. This reservoir of stem cells, identified by distinct markers which are listed in Table 2, can proliferate again at any time and cause a recurrence of the cancer. There is evidence that metformin can selectively act in stem cells to inhibit the cancer proliferation and sensitize them to enhance the effects of other treatments (43, 44). It is important to highlight that the cells must express the membrane transporter OCT1 in order for metformin to correctly fulfill its antineoplastic properties. This transporter allows the mitochondrial membrane potential to attract metformin into the mitochondria, thus reaching high concentrations. However, the expression of OCT1 in prostate cancer stem cells has not been demonstrated yet (45).

3.6. Discussion of the antineoplastic effects of metformin

A decrease in tumor proliferation was determined in vitro in mice, however, the doses used in this type of studies are between 100 and 300 times higher than those used in standard antidiabetic treatments (14).

- Conclusion

Whilst evidence outlines the potential benefits of metformin in PCa, further research is needed to explain critical questions that remain unanswered. For example, it is still unclear whether the effects of metformin are limited to specific populations and tumors, whether the conventional antidiabetic dose is the optimal anticancer dose, or whether metformin plays a role in the prevention or in the treatment of PCa, or in both. In addition, the potential side effects have not been studied thoroughly enough.

Metformin is an oral antidiabetic drug with antitumor effects in vitro. However, the true potential of metformin as an antineoplastic agent is yet to be established. There are numerous confounding factors in retrospective studies and there is a lack of research involving non-diabetics. This raises the question of whether it is actually the management of diabetes, and not metformin itself, that lowers the risk of developing cancer and increases the survival rate in cancer patients (particularly those undergoing ADT). Yet again, further, more extensive studies are needed to assess the long-term effects of metformin.

Preliminary evidence on the potential benefits of metformin in PCa, especially when used in combined therapy, justifies further investigation. Future studies should follow critical and rigorous methodology to determine if the effects of metformin can have real clinical impact.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29.

- Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J. 2000;348(3):607–14.

- Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):251–62.

- Miller RA, Birnbaum MJ. An energetic tale of AMPK-independent effects of metformin. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2267–70.

- Zingales V, Distefano A, Raffaele M, Zanghi A, Barbagallo I, Vanella L. Metformin: A Bridge between Diabetes and Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017; 7:243.Whitburn J, Edwards CM, Sooriakumaran P.

- Das TP, Suman S, Alatassi H, Ankem MK, Damodaran C. Inhibition of AKT promotes FOXO3a- dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7:e2111.

- Wang Y, Yao B, Wang Y, Zhang M, Fu S, Gao H, et al. Increased FoxM1 expression is a target for metformin in the suppression of EMT in prostate cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2014; 33(6):1514–22.

- Akinyeke T, Matsumura S, Wang X, Wu Y, Schalfer ED, Saxena A, et al. Metformin targets c-MYC oncogene to prevent prostate cancer. 2013; 34(12):2823–32.

- Demir U, Koehler A, Schneider R, Schweiger S, Klocker H. Metformin anti-tumor effect via disruption of the MID1 translational regulator complex and AR downregulation in prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:52.

- Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Bolanowski M, Kręcicki T, Zatoński T. Diabetes and cancer: a review of current knowledge. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2016;124:263–75.

- Qin G, Xu F, Qin T, Zheng Q, Shi D, Xia W, et al. Palbociclib inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in breast cancer via c-Jun/ COX-2 signaling pathway. 2015; 6(39):41794–808.

- Hitron A, Adams V, Talbert J, Steinke D. The influence of antidiabetic medications on the development and progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012; 36(4):e243–50.

- Tseng CH. Diabetes, metformin use, and colon cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012; 167(3):409–16.

- Ben Sahra I, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an anti-tumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. 2008;27(25):3576–86.

- Whitburn J, Edwards C, Sooriakumaran P. Metformin and Prostate Cancer: a New Role for an Old Drug. Current Urology Reports. 2017;18(6):46.

- Joshua AM, et al. A pilot ‘window of opportunity’ neoadjuvant study of metformin in localised prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17(3):252–8.

- Bowker SL, et al. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):254–8.

- Libby G, et al. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1620–5.

- Bo S, Ciccone G, Rosato R, Villois P, Appendino G, Ghigo E, et al. Cancer mortality reduction and metformin: a retrospective cohort study in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012; 14(1):23–9.

- Wu GF, Zhang XL, Luo ZG, Yan JJ, Pan SH, Ying XR, et al. Metformin therapy and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015; 8(8):13089–98.

- Yin M, Zhou J, Gorak EJ, Quddus F. Metformin is associated with survival benefit in cancer patients with concurrent type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2013;18:1248–55.

- Kordes S, et al. Metformin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):839–47.

- Sayed R, et al. Metformin addition to chemotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: an open label randomized controlled study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6621–6.

- Reni M, et al. (Ir)relevance of metformin treatment in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: an open-label, randomized phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(5):1076–85.

- Rastmanesh R, Hejazi J, Marotta F, Hara N. Type 2 diabetes: a protective factor for prostate cancer? An overview of proposed mechanisms. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12:143–8.

- Litwin MS, Tang H. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. 2017; 317(24): 2532-2542. doi:10.1001

- Tseng CH. Metformin significantly reduces incident prostate cancer risk in Taiwanese men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2831–7.

- Etheridge T, Damodaran S, Schultz A, Richards KA, Gawdzik J, Yang B, et al. Combination therapy with androgen deprivation for hormone sensitive prostate cancer: A new frontier. AJUR. 2019;6:57-64.

- Ojeda S, Lloret M, Naranjo A, Déniz F, Chesa N, Domínguez C, et al. Deprivación androgénica en cáncer de próstata y riesgo de fractura a largo plazo. Actas Urol Esp. 2017; 41(8): 491-496.

- Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, Oudard S, Priou F, Esterni B, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149-58.

- Gamat M, McNeel DG. Androgen deprivation and immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. 2017;24:297-310. doi:10.1530.

- Ahmadi H, Daneshmand S. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: long-term safety and patient outcomes. 2014;5:63-70. doi: 10.2147.

- Richards KA, Liou JI, Cryns VL, Downs TM, Abel EJ, Jarrard DF. Metformin use is associated with improved survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol. 2018;200:1256-63. doi: 10.1016.

- Nobes JP, Langley SE, Klopper T, et al. A prospective, randomized pilot study evaluating the effects of metformin and lifestyle intervention on patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy. BJU Int. 2012;109:1495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.

- Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010; 18:11-22.

- Kirby M, Hirst C, Crawford ED. Characterising the castration-resistant prostate cancer population: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011; 65:1180-1192.

- Edlind MP, Hsieh AC. PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J Androl. 2014; 16(3):378-386.

- Delma MI. Three May Be Better Than Two: A Proposal for Metformin Addition to PI3K/Akt Inhibitor-antiandrogen Combination in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. 2018; 10(10):e3403.

- Rothermundt C, Hayoz S, Templeton AJ, et al. Metformin in chemotherapy-naive castration resistant prostate cancer: a multicenter phase 2 trial (SAKK 08/09). Eur Urol. 2014; 66:468- 474.

- Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013; 20: R83-R99.

- Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011; 19:575-586.

- Khan KH, Wong M, Rihawi K, Bodla S, Morganstein D, Banerji U, Molife LR. Hyperglycemia and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) inhibitors in phase I trials: incidence, predictive factors, and management. 2016, 21: 855-860.

- Zong Y, Goldstein AS. Adaptation or selection-mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013; 10: 90–98.

- Saini N, Yang X. Metformin as an anti-cancer agent: actions and mechanisms targeting cancer stem cells. 2017; 50: 133-143. doi: 10.1093

- Pollak M. Potential applications for biguanides in oncology. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3693–3700.

AMU 2019. Volumen 1, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

15/04/2019 22/04/2019 31/05/2019

Cita el artículo: Serrano-Herrera A, Rodríguez-Martínez C, Domingo-López P, Girona-Torres A, Sola-Montijano P, Domingo-López J. Las fronteras de la metformina: entre la diabetes y el cáncer de próstata. AMU. 2019; 1(1): 138-51