Ramos Cela, Miguel ¹; Medina Martínez, Alberto Jesús ¹; Vera Martín, Ignacio ¹ *

1 Universidad de Granada, Facultad de Medicina

* Corresponding Author: i.veram@alumnos.upm.es

Resumen

La Listeria monocytogenes (LM) es una causa común de infecciones del Sistema Nervioso Central (SNC), especialmente en pacientes inmunodeprimidos, lactantes y ancianos. El hecho que convierte a la LM en una bacteria peligrosa es que puede evadir fácilmente el sistema inmunitario y transmitirse por vía fecal-oral causando una enfermedad llamada listeriosis. No obstante, la incidencia actual de una infección por Listeria monocytogenes es de 3 a 6 casos por millón, pero su prevalencia ha ido en aumento. Esta bacteria se vuelve especialmente patógena cuando infecta el SNC, razón por la cual la neurolisteriosis puede representar hasta la mitad de los casos de listeriosis invasiva, siendo el resto de casos generalmente bacteriemia aislada o enfermedad en el embarazo. Existe una amplia lista de factores de riesgo relacionados con la listeriosis, como las neoplasias, el alcoholismo y/o la hepatopatía, el VIH/SIDA o la diabetes, pero sólo algunos de ellos están estrechamente relacionados con la neurolisteriosis. Estos son el entorno hormonal en el embarazo, el envejecimiento, la corticoterapia y las comorbilidades inmunosupresoras. En esta revisión nos centramos en las vías de infección del LM y en los principales factores de riesgo que permiten a esta bacteria actuar y generar complicaciones asociadas al sistema nervioso.

Palabras clave: Listeria monocytogenes, Sistema inmunitario, listeriosis, neurolisteriosis, Sistema Nervioso Central, factores de riesgo.

Keyword: Listeria monocytogenes, immune system, listeriosis, neurolisteriosis, Central Nervous System, risk factors.

1. Introducción

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) es un bacilo Gram + transmitido por los alimentos que causa la listeriosis, que tiene la mayor tasa de hospitalización entre las enfermedades transmitidas por los alimentos (1). Es la única especie de Listeria conocida con potencial patógeno. La listeriosis humana se manifiesta como septicemia, invasión del SNC, que se denomina Neurolisteriosis (NL), e infecciones materno-fetales, así como formas raras de infecciones localizadas. Los trastornos del SNC asociados a la listeriosis son especialmente preocupantes, ya que se estima que representan alrededor de un tercio del total de casos (2).

La LM puede encontrarse en una amplia gama de entornos, como el suelo, el agua y las heces. Puede colonizar plantas, aves y un amplio grupo de mamíferos. Esta amplia presencia en la naturaleza favorece la infección del ganado y los cultivos, a través de los cuales puede entrar fácilmente en la cadena alimentaria humana y suponer una amenaza sanitaria (3). Aunque su existencia se descubrió ya en la década de 1920 y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial causó terribles brotes de infecciones mortales del sistema nervioso central y abortos, no fue hasta 1983 cuando se demostró y se comprendió plenamente su transmisión a través de los alimentos (4). Desde entonces, las infecciones por LM han aumentado rápidamente como un importante problema epidemiológico humano debido a la gran industrialización del negocio alimentario y la rápida distribución de sus productos, el hábito general de refrigerar los alimentos (que permite el crecimiento de la LM) y el aumento del número y la duración de la vida de los pacientes inmunodeprimidos (debido al mayor número de fármacos inmunosupresores recientemente aprobados), que son la principal población de riesgo para la listeriosis (5). Esto ilustra la necesidad de implementar programas de vigilancia microbiológica y epidemiológica bien estandarizados, que son extremadamente efectivos para prevenir brotes a gran escala. De hecho, ha sido en los países poco desarrollados, que carecen de las estrategias mencionadas, donde se han producido los brotes más destructivos, como el de Sudáfrica en 2017, que es el mayor conocido hasta la fecha (6).

Neurolisteriosis: epidemiología y tratamiento

La bacteriemia y la NL son la complicación más mortífera de la infección por listeriosis, siendo la NL la que más discapacidades provoca en pacientes perinatales y no perinatales, como discapacidad intelectual, epilepsia, alteraciones motoras, pérdida de visión e ictus (7). El tratamiento de la infección por LM es diferente dependiendo de si existe afectación neuronal. El estudio MONALISA encontró que el tratamiento coadyuvante con corticoides como la dexametasona incrementa la mortalidad de los pacientes con NL mientras que el uso de Cotrimoxazol, debido a su penetración en el SN, es una alternativa favorable en estos pacientes (2). Del mismo modo, el Linezolid podría ser otra opción adecuada debido a su alta penetración en el Líquido Cefalorraquídeo (LCR) (8). Como es lógico, se ha demostrado que un retraso en el tratamiento de la NL se asocia fuertemente con peores resultados (9).

Diagnóstico y presentación clínica

La infección por LM suele diagnosticarse erróneamente porque los síntomas prodrómicos son inespecíficos y los signos meníngeos son infrecuentes. En caso de neuroinvasión, la LM puede causar meningitis, meningoencefalitis o formación de abscesos en el cerebro y la médula espinal (10). La rombencefalitis es una forma particular de afección por encefalitis listeriosis que afecta principalmente al tronco cerebral y al cerebelo (rombencefalo). El pronóstico de la neurolisteriosis es especialmente preocupante: el 30% de los individuos que desarrollan esta manifestación clínica tienen una tasa de mortalidad de 3 meses, y más del 60% de los pacientes nunca se recuperan del todo (2). Además, como mencionamos anteriormente, la neurolisteriosis está casi siempre relacionada con alguna otra comorbilidad, en su mayoría asociada a algún tipo de inmunosupresión (11).

Por tanto, la neurolisteriosis es el peor resultado clínico tras una infección por LM, ya que conlleva una elevada morbilidad y mortalidad. Aunque se conocen algunos factores de riesgo para contraer esta infección, todavía no hay pruebas sólidas sobre ellos. El objetivo de este trabajo es revisar las infecciones del SNC causadas por LM, haciendo especial hincapié en los factores de riesgo asociados a una peor evolución clínica. Es de suma importancia comprender y evaluar estos factores de riesgo para establecer mejores métodos de diagnóstico con el fin de mejorar el futuro tratamiento que pueda recibir el individuo, ampliando nuestro conocimiento global de las causas que finalmente conducen a las alteraciones fisiológicas relacionadas con el sistema nervioso.

2. Características fisiológicas y moleculares de LM

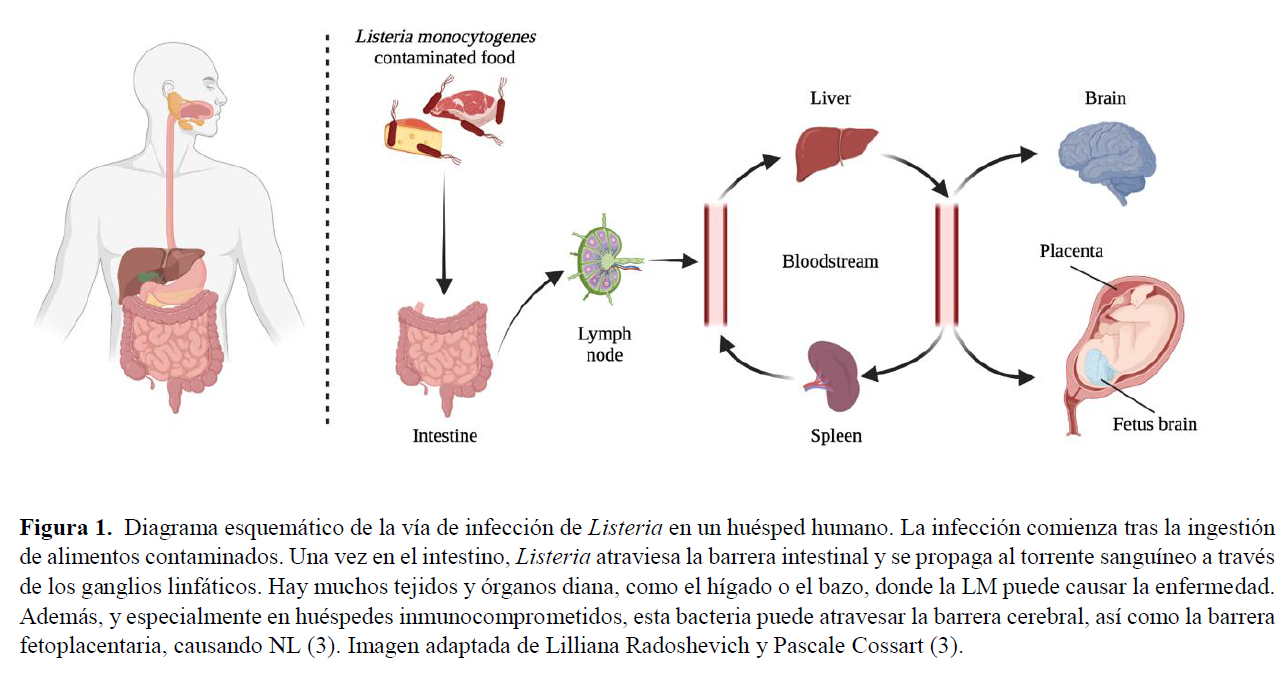

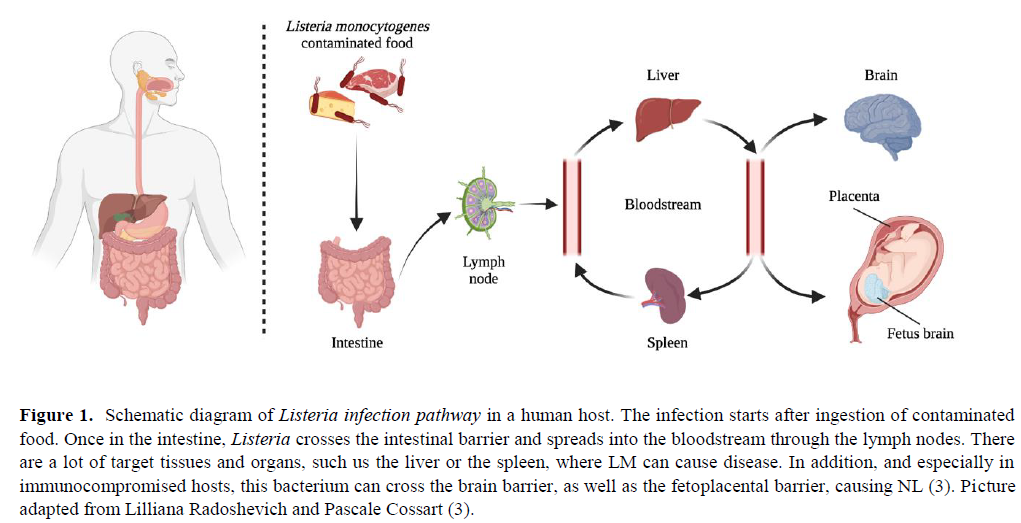

Los síntomas clínicos tras la infección pueden ser bastante graves y diversos debido a las características fisiológicas del proceso de colonización: la bacteria es capaz de atravesar la barrera intestinal, la barrera hematoencefálica y la barrera placentaria en las mujeres embarazadas, repitiendo el proceso en el feto (12). El LM también puede causar la invasión del SNC a través de una ruta neural retrógrada (11). Una característica llamativa del LM es que la mayor parte de su ciclo vital ocurre en el citoplasma de las células por las que tiene Esto es promovido por una proteína de invasión bacteriana expuesta en su superficie que induce la fagocitosis en células que normalmente no son fagocíticas. Los huéspedes inmunocomprometidos, específicamente con una inmunidad celular deficiente, son los más propensos a la NL. En este escenario, los LM pueden multiplicarse rápidamente y sin restricciones en los hepatocitos, desde donde se diseminan de forma hematógena al cerebro y a otros lugares. El camino fisiológico dentro del organismo, así como el mecanismo que emplea la bacteria para entrar en la célula, escapar de la vacuola fagocítica y diseminarse de una célula a otra mediante la motilidad basada en la actina, se resumen en las figuras 1 y 2.

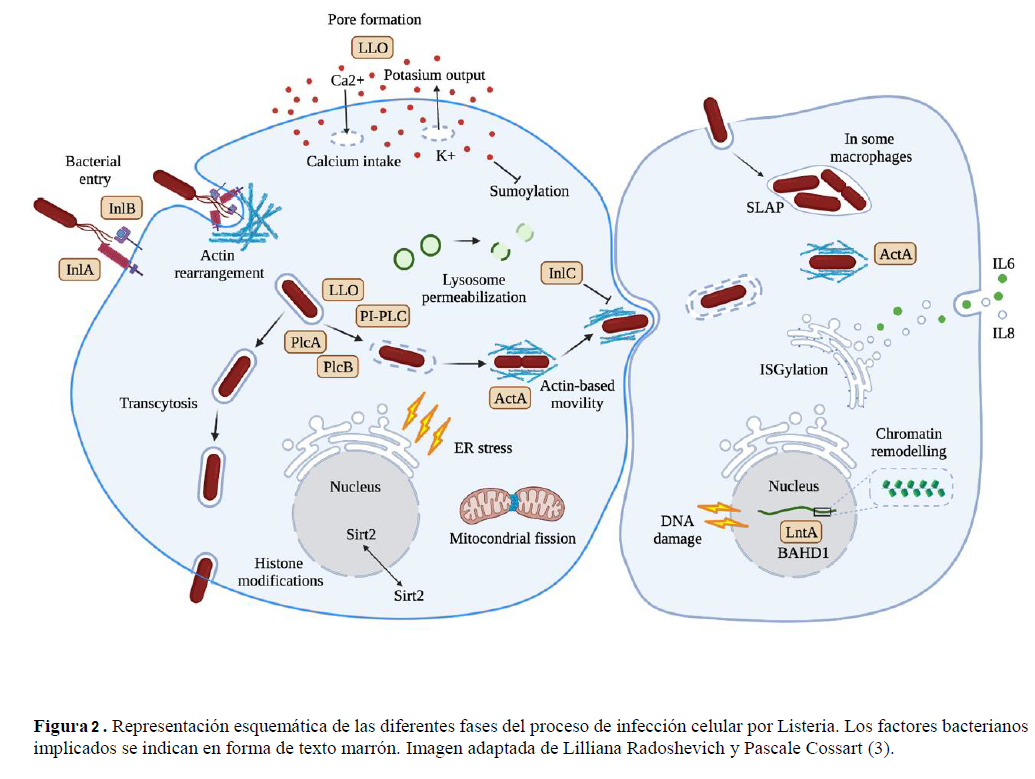

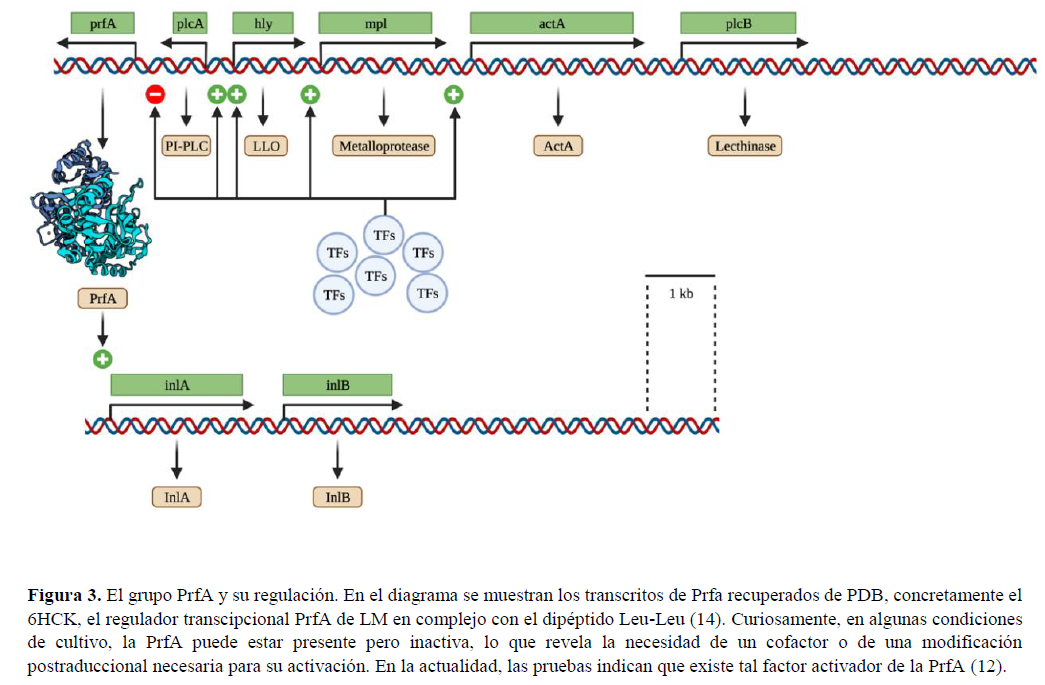

La entrada bacteriana no fagocítica está mediada por al menos dos factores: Internalina A (InlA) y B (InlB). El primer paso se produce en las células no fagocíticas, como las células epiteliales, a través de la endocitosis mediada por receptores y por eso esta bacteria puede propagarse a través de las barreras epiteliales. La salida de la vacuola requiere la expresión de la Listeriolisina O (LLO), una toxina formadora de poros que en algunas células puede funcionar de forma sinérgica o ser sustituida por una fosfolipasa C específica de fosfatidilinositol (PI-PLC, por sus siglas en inglés). La actividad formadora de poros de la LLO extracelular conduce a cambios internos en los procesos celulares distintivos de la infección por LM. Estos incluyen cambios en la modificación de las histonas, la deSUMOilación, la fisión mitocondrial, el estrés del retículo endoplásmico (RE) y la permeabilización lisosomal (13). El escape de la vacuola ocurre con más frecuencia que el proceso de transcitosis, y la lisis de la vacuola de dos membranas es realizada por la lecitinasa A (PlcA) y B (PlcB). Por otro lado, en las células caliciformes, puede transcitar a través de la célula dentro de una vacuola, y en algunos macrófagos, puede replicarse en fagosomas espaciosos que contienen Listeria (SLAPs, por sus siglas en inglés) (14). La mayoría de los genes que codifican estos factores de virulencia se agrupan en el regulón PrfA, situado en una región de 10 kb del cromosoma bacteriano. El regulón PrfA recibe su nombre porque todos los genes de virulencia conocidos están bajo el control absoluto o parcial de una proteína activadora pleiotrópica PrfA (14). Este cluster se representa en la Figura 2 y la estructura del transcrito PrfA se muestra en la Figura 3. Tras el escape vacuolar, el movimiento intracelular de la bacteria requiere la expresión de la proteína inductora del ensamblaje de actina (ActA) y la polimerización de la actina. Esta molécula permite la motilidad basada en la actina, que es la forma en que el agresor puede propagarse de célula a célula.

La actividad de los potentes factores de virulencia provoca una plétora de efectos en la célula de mamífero infectada. Las células caliciformes son células epiteliales columnares simples que secretan mucinas gelificantes, como la mucina MUC5AC (15). En estas células, la proteína A dirigida al núcleo de Listeria (LntA, por sus siglas en inglés) interactúa con el complejo de la proteína que contiene el dominio de homología adyacente Bromo 1 (BAHD1, por sus siglas en inglés) e induce la desacetilación de la histona 3 en la lisina 18, lo que provoca cambios en el empaquetamiento de la cromatina. Esta modificación va a alterar la expresión génica aguas abajo. Además, la infección también provoca daños en el ADN. La forma en que la célula huésped lucha contra la infección por Listeria es regulando al alza varios efectores antibacterianos, por ejemplo, ISG15, que es el actor principal del proceso de ISGilación que se basa en una modificación covalente de las proteínas del RE y del Golgi que modulan la expresión de las citoquinas IL6 e IL8 (16).

3. Factores de riesgo relevantes

El entorno hormonal durante el proceso de embarazo crea una supresión local de la CMI en la interfaz materno-fetal (17). Por lo tanto, el LM puede llegar al feto desde la sangre materna a través de la placenta. La LM también puede infectar al bebé durante el parto o a través de una transmisión nosocomial (18). Los signos y síntomas de esta infección incluyen lesiones granulomatosas diseminadas con microabscesos (19) e hidrocefalia y retraso en el desarrollo neurológico (20). Aunque la mayoría de los casos se observan durante el segundo y tercer trimestre, posiblemente, esto refleja un sesgo en el que las pérdidas fetales tempranas causadas por la LM no se diagnostican normalmente (12). Por otra parte, generalmente se cree que el SN de la madre no tiene un mayor riesgo de infección por estar embarazada. De hecho, esto sólo se ha visto muy excepcionalmente (21).

Se ha demostrado que la vejez es un fuerte factor de riesgo para la NL. Esto se debe a la pérdida parcial de la inmunidad de las células T que se produce en el proceso de envejecimiento. A pesar de ello, la bacteriemia es más frecuente a partir de los 75 años, mientras que la NL aparece más en el intervalo de 45-65 años (22).

El lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es una enfermedad autoinmune en la que se ataca a las células y tejidos sanos de todo el organismo, y la infección es una de las principales causas en estos pacientes. Un informe de 26 casos en México con LES (23) encontró que, aunque entre los pacientes con LES la neurolisteriosis era extremadamente rara (0,53- 2,25%), su presentación clínica es inespecífica, y su diagnóstico puede confundirse fácilmente con un brote de lupus neuropsiquiátrico. De hecho, el LM es uno de los tres principales patógenos causantes de infecciones del SNC en pacientes con LES (24). Sin embargo, no hay pruebas suficientes para confirmar si el LES aumenta el riesgo de infección por LM, pero está claro que empeora su pronóstico.

Los estudios (25) indican que el diagnóstico precoz a partir de cultivos de sangre y tejidos determina la eficacia y el éxito del futuro tratamiento.

En un estudio prospectivo de 16 millones de personas en los Países Bajos (25) encontraron que de todas las meningitis bacterianas entre los pacientes diabéticos más del 6% estaban causadas por LM, y que estos pacientes tenían un riesgo 2 veces mayor de desarrollar meningitis, debido a una inmunidad celular deteriorada con una eficacia disminuida de los leucocitos polimorfonucleares, monocitos y linfocitos T. Otro informe de caso (26) constata el desarrollo de una rombencefalitis tras una infección por Listeria, en el que los antecedentes médicos del paciente incluían hipertensión, diabetes de tipo II y, lo que es más importante, cirrosis criptogénica. Como en casi todos los informes de casos, destacan la importancia de un diagnóstico precoz para el futuro tratamiento antibiótico y de una resonancia magnética cerebral urgente para los pacientes con signos progresivos incapacitantes en el tronco cerebral.

La Esclerosis Múltiple (EM) por sí misma no se considera un factor de riesgo para desarrollar NL, pero su tratamiento incluye alemtuzumab, un anticuerpo monoclonal anti-CD52 que provoca una depleción masiva de células T CD8+, lo que puede potenciar la replicación del LM tras la infección (27). Hasta ahora, se ha informado de muy pocos casos de pacientes con EM bajo tratamiento con alemtuzumab que hayan desarrollado NL, pero los autores creen que estos casos podrían estar muy infrarrepresentados. Por todo ello, es especialmente importante seguir de cerca en los pacientes con EM el brote de infecciones por LM, ya que la mayoría de ellos podrían ser portadores sanos antes del tratamiento con alemtuzumab, ya que desarrollaron la enfermedad en cuestión de horas tras la administración. En estos casos, se cree que la mejor opción es un tratamiento profiláctico con antibióticos. En el estudio MONALISA (2) se observó que los pacientes con neurolisteriosis tratados con corticoides adyuvantes tenían un peor resultado en comparación con los pacientes sin corticoterapia. Como ya se ha explicado, la LM es una bacteria facultativa intracelular. Por tanto, una supresión o disminución del CMI va a facilitar su diseminación y neuroinvasión. Según el estudio MONALISA, estadísticamente las comorbilidades más frecuentes que aumentan la posibilidad de desarrollar NL son el cáncer de órgano sólido y la diabetes mellitus.

En este estudio también describen todas las posibles causas inmunosupresoras de la NL que son la ingesta diaria de alcohol (que supone más de tres bebidas al día), la cirrosis, la diabetes mellitus, la enfermedad renal terminal, el cáncer de órgano sólido, las neoplasias hematológicas, el trasplante de células madre hematopoyéticas, el trasplante de órganos sólidos, la asplenia, la neutropenia preexistente, la linfopenia preexistente, la infección por VIH, las enfermedades inflamatorias intestinales, los trastornos reumáticos inflamatorios, otras enfermedades autoinmunes y la inmunodeficiencia congénita (2).

4. Conclusiones

Esta revisión es un estudio con ciertas limitaciones. Cuando se habla de factores de riesgo de infecciones bacterianas, hay muchos que son comunes a diferentes infecciones en diferentes partes del cuerpo. Dado que nuestro trabajo se centra en los factores de riesgo de la NL, no hay muchos trabajos que recojan datos tan específicos, y suelen centrarse en sintomatología más diversa o incluso en otras infecciones causadas por otras bacterias.

Hay una serie de factores de riesgo como el alcoholismo, la diabetes, los malos hábitos nutricionales, etc. que son generales para la listeriosis. Por ello, hemos decidido no analizarlos todos y centrarnos exclusivamente en los factores de riesgo específicos de la NL. Es importante aclarar que, en este sentido, la revisión bibliográfica no es completa ni perfecta. Podría mejorarse haciendo un meta-análisis de todos los factores de riesgo relacionados con la listeriosis y no sólo de los exclusivos de las alteraciones del SNC.

Sin embargo, el futuro de la investigación sobre la NL es prometedor, ya que aún queda mucha información por extraer de una infección típica de LM en el Sistema Nervioso Central. De hecho, nuestro trabajo ha evidenciado una tendencia creciente de investigación dentro de este campo de estudio, y a medida que se sigan publicando más casos clínicos la comunidad científica tendrá un mejor conocimiento de esta enfermedad. Por lo tanto, esta revisión podría ayudar a los futuros investigadores a organizar más fácilmente la información recopilada sobre LM y los factores de riesgo asociados a su infección neuronal.

La neuroinvasión debida a LM puede causar varias formas de encefalitis y meningitis con diversas manifestaciones clínicas, y a día de hoy la LM sigue siendo un importante problema de salud pública, sobre todo en ancianos, lactantes, inmunodeprimidos y personas con neoplasias que puedan influir de algún modo en la función del sistema inmunitario. En el caso de los pacientes con diagnóstico clínico de rombencefalitis y meningitis bacteriana aguda, el reconocimiento de los síntomas causados por la infección listerial desempeña un papel fundamental para permitir el diagnóstico y el tratamiento tempranos y garantizar una evolución óptima del paciente sin secuelas neurológicas Dado que la LM sólo es sensible a ciertos antibióticos, es importante realizar un diagnóstico microbiológico temprano que confirme el infectino. La LM es difícil de aislar del LCR, pero no tanto de la sangre u otros tejidos infectados. Además del diagnóstico microbiológico, las imágenes de RM son extremadamente importantes para demostrar la predilección de la infección listerial por el tronco cerebral y el cerebelo. Como se ha explicado anteriormente, existen varios escenarios en los que esta infección puede ser considerablemente más peligrosa y suponer una situación de riesgo vital para el paciente. En las mujeres embarazadas es fundamental el diagnóstico y el seguimiento detallado del tratamiento por parte de los médicos, ya que está en riesgo no sólo la vida de la mujer, sino también la del feto, con las complicaciones adicionales que puede ocasionar un aborto espontáneo o el nacimiento de un bebé muerto. Aparte de eso, puede haber pacientes con el sistema inmunitario deteriorado debido a una gran variedad de factores. Los tratamientos inmunosupresores, como los corticosteroides o los anticuerpos monoclonales, pueden empeorar el curso de una infección preexistente o nueva, y en estos casos es urgente un tratamiento profiláctico con antibióticos tras un diagnóstico precoz. Las afecciones autoinmunes como el Lupus Eritematoso también se encuentran entre la lista de factores de riesgo que pueden influir en el desarrollo de situaciones neuroinvasivas por LM, con una sintomatología muy inespecífica.

Por todo lo expuesto anteriormente, entre estos pacientes un diagnóstico precoz es aún más relevante y puede cambiar el curso de la infección. Se debe realizar siempre una evaluación precisa de la sintomatología y un seguimiento continuo. El LCR en la infección listerial suele revelar un aumento del recuento de leucocitos, generalmente con predominio de células polimorfonucleares, aumento de las proteínas y niveles normales de glucosa. Además, aunque es complicado, deben desarrollarse más y mejores métodos de cultivo celular para confirmar la presencia de LM, especialmente en el LCR. Y, por último, debe considerarse el tratamiento profiláctico con antibióticos cuando se sospeche que los pacientes son portadores sanos.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Agradecemos a los profesores Pablo Redruello Guerrero, Mario Rivera Izquierdo y Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos- Bossini su ayuda para realizar los presentes estudios.

Conflicts of interest

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Financiación

Ninguna

Referencias

1. Hedberg Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States (Response). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(7):1338–1338.

2. Charlier C, Perrodeau É, Leclercq A, Cazenave B, Pilmis B, Henry B, et Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017;17(5):510–9.

3. Walland J, Lauper J, Frey J, Imhof R, Stephan R, Seuberlich T, et Listeria monocytogenes infection in ruminants: Is there a link to the environment, food and human health? A review. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2015;157(6):319–28.

4. Schlech New perspectives on the gastrointestinal mode of transmission in invasive Listeria monocytogenes infection. Clinical and investigative medicine Medecine clinique et experimentale. 1984;7(4):321–4.

5. Lecuit M. <scp> Listeria monocytogenes </scp> , a model in infection biology. Cellular Microbiology. 2020;22(4).

6. Thomas J, Govender N, McCarthy KM, Erasmus LK, Doyle TJ, Allam M, et al. Outbreak of Listeriosis in South Africa Associated with Processed Meat. New England Journal of 2020;382(7):632–43.

7. de Noordhout CM, Devleesschauwer B, Angulo FJ, Verbeke G, Haagsma J, Kirk M, et al. The global burden of listeriosis: a systematic review and meta- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014; 14(11):1073–82.

8. Callapina M, Kretschmar M, Dietz A, Mosbach C, Hof H, Nichterlein Systemic and Intracerebral Infections of Mice with Listeria monocytogenes Successfully Treated with Linezolid. Journal of Chemotherapy. 2001;13(3):265–9.

9. Arslan F, Meynet E, Sunbul M, Sipahi OR, Kurtaran B, Kaya S, et al. The clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of neuroinvasive listeriosis: a multinational European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2015;34(6):1213–21.

10. Drevets DA, Leenen PJM, Greenfield RA. Invasion of the central nervous system by intracellular Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):323–47.

11. Clauss HE, Lorber Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2008 Jul 11;10(4):300–6.

12. Charlier C, Disson O, Lecuit M. Maternal-neonatal Virulence. 2020;11(1):391–7.

13. Cossart P, Lecuit Interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells during entry and actin-based movement: bacterial factors, cellular ligands and signaling. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(14):3797–806.

14. Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2018;16(1):32–46.

15. Ma J, Rubin BK, Voynow JA. Mucins, Mucus, and Goblet Chest. 2018;154(1):169–76.

16. Krypotou E, Scortti M, Grundström C, Oelker M, Luisi BF, Sauer-Eriksson AE, et Control of Bacterial Virulence through the Peptide Signature of the Habitat. Cell Reports. 2019;26(7):1815-1827.e5.

17. Sappenfield E, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP. Pregnancy and Susceptibility to Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and 2013;2013:1–8.

18. MYLONAKIS E, PALIOU M, HOHMANN EL, CALDERWOOD SB, WING EJ. Listeriosis During Medicine. 2002;81(4):260–9.

19. Janakiraman V. Listeriosis in pregnancy: diagnosis, treatment, and Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):179–85.

20. Curcio AM, Shekhawat P, Reynolds AS, Thakur Neurologic infections during pregnancy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;172:79–104.

21. Adriani KS, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Bacterial meningitis in pregnancy: report of six cases and review of the Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(4):345–51.

22. Ricci A, Allende A, Bolton D, Chemaly M, Davies R, Fernández Escámez PS, et Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready‐to‐eat foods and the risk for human health in the EU. EFSA Journal. 2018;16(1).

23. Horta-Baas G, Guerrero-Soto O, Barile-Fabris Central nervous system infection by Listeria monocytogenes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of 26 cases, including the report of a new case. Reumatologia clinica. 9(6):340– 7.

24. Hung J-J, Ou L-S, Lee W-I, Huang J-L. Central nervous system infections in patients with systemic lupus J Rheumatol. 2005;32(1):40–3.

25. van Veen KEB, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Bacterial meningitis in diabetes patients: a population-based prospective Sci Rep. 2016;6:36996.

26. Carrillo-Esper R, Carrillo-Cordova LD, Espinoza de los Monteros-Estrada I, Rosales-Gutiérrez AO, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez Rhombencephalitis by Listeria monocytogenes in a cirrhotic patient: a case report and literature review. Ann Hepatol. 12(5):830– 3.

27. Mazzitelli M, Barone S, Greco G, Serapide F, Valentino P, Giancotti A, et al. Listeria infection after treatment with alemtuzumab: a case report and literature review. Would antibiotic prophylaxis be considered? Infez Med. 2020;28(2):258–62.

Infection of Listeria monocytogenes associated to the central nervous system: Cell pathogenesis, diagnosis and risk factors

Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a common cause of Central Nervous System (CNS) infections, especially in immunosuppressed patients, infants, and elderly people. The fact that makes LM a dangerous bacterium is that it can easily evade the immune system and be transmitted by the fecal-oral route causing a malignancy called listeriosis. Nonetheless, the current incidence of a Listeria monocytogenes infection is 3-6 cases per million, but its prevalence has been increasing. These bacteria become especially pathogenic when infecting the CNS, the reason why neurolisteriosis can account for as much as half the cases of invasive listeriosis, the remaining cases being usually isolated bacteremia or disease in pregnancy.

There is an ample list of risk factors related with listeriosis such us malignancies, alcoholism and/or liver disease, HIV/AIDS, or diabetes, but only some of them are closely interconnected with neurolisteriosis. These are the hormonal environment in pregnancy, aging, corticotherapy and immunosuppressive comorbidities. In this review we focus on the LM infection pathways and the main risk factors that let this bacteria act and generate nervous system-associated complications.

Keyword: Listeria monocytogenes, immune system, listeriosis, neurolisteriosis, Central Nervous System, risk factors.

1. Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a foodborne Gram + bacillus which causes listeriosis, having the highest hospitalization rate among foodborne diseases (1). It is the only known Listeria species with pathogenic potential. Human listeriosis manifests as septicemia, CNS invasion, which is called Neurolisteriosis (NL), and maternal-fetal infections, as well as rare forms of localized infections. CNS disorders associated with Listeriosis are especially concerning as they are estimated to represent about one third of the total cases (2).

LM can be found in a wide range of environments such as soil, water and feces. It can colonize plants, birds and an ample group of mammals. This large presence in nature favors the infection of livestock and crops, through which it can easily enter the human food chain supply and pose as a sanitary threat (3). Although its existence was discovered as early as the 1920s and after World War II it caused terrible outbreaks of fatal CNS infections and miscarriages, it was not until 1983 when its food-borne transmission was proven and fully understood (4). Since then, LM infections have escalated quickly as a major human epidemiologic issue due to the vast industrialization of the alimentary business and rapid distribution of its products, the general habit of refrigerating food (which enables LM growth), and the increased number and life-span of immunosuppressed patients (due to the increased number of newly approved immunosuppressive drugs), who are the principal risk population for listeriosis (5). This illustrates the need of implementation of well-standardized, microbiological and epidemiologic surveillance programs, which are extremely effective to prevent large-scale outbreaks. In fact, it has been in poorly developed countries, which lack the mentioned strategies, where the most destructive outbreaks have taken place, such as the one in South Africa in 2017 which is the largest ever known still to this day (6).

Neurolisteriosis: epidemiology and treatment

Bacteremia and Neurolisteriosis (NL) are the deadliest complication of listeriosis infection, being NL the one that causes more disability in perinatal and not perinatal patients such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, motor impairment, vision loss and stroke (7). The treatment of infection by LM is different depending on if neural affectation exists. The MONALISA study found that the adjunctive treatment with corticoids such as dexamethasone increment the mortality of patients with NL meanwhile the use of Cotrimoxazole, due to this penetration in the NS, is a favorable alternative in these patients (2). In a similar way, Linezolid could be other suitable option due to his high penetration in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) (8). Unsurprisingly, it has been demonstrated that a delay in the treatment of NL is strongly associated with worse outcomes (9).

Diagnosis and clinical presentation

LM infection is often misdiagnosed because the prodromal symptoms are nonspecific and meningeal signs are uncommon. In the case of neuroinvasion, LM can cause meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or abscess formation in the brain and spinal cord (10). Rhombencephalitis is a particular form of encephalitis listeriosis affection that affects primarily the brain stem and cerebellum (rhombencephalon). Neurolisteriosis prognosis is especially concerning: 30% of the individuals who develop this clinical manifestation have a 3-month mortality rate, and above 60% of patients never fully recover (2). Moreover, as we mention before, neurolisteriosis is almost always related to some other comorbidity, mostly associated with some type of immunosuppression (11).

Therefore, neurolisteriosis is the worst clinical outcome following a Listeria monocytogenes infection, as it entails high morbidity and mortality. Although some risk factors for contracting this infection are known, there is still no solid evidence on them. The aim of this paper is to review CNS infections caused by LM, with special emphasis on risk factors associated with a worse clinical course. It is of paramount importance to understand and evaluate these risk factors to establish better diagnostic methods in order to improve the future treatment the individual may receive, by broadening our global knowledge of the causes that ultimately lead to neural-related physiological impairments.

2. Physiological and molecular pathogenic features of Listeria

Clinical symptoms after infection can be quite severe and diverse due to the physiological characteristics of the colonization process: the bacterium is able to cross the intestinal barrier, the blood-brain barrier, and the placental barrier in pregnant women, repeating the process in the fetus (12). LM can also cause invasion of the CNS through a retrograde neural route (11). A striking feature of LM is that most of its life cycle occurs in the cytoplasm of the cells that it has tropism for. This is promoted by a bacterial invasion protein exposed in its surface which induces phagocytosis in cells that are normally non-phagocytic. Immunocompromised hosts, specifically with deficient Cell- mediated immunity (CMI), are the most prone to neurolisteriosis. In this scenario, LM can rapidly multiply unrestrictedly in the hepatocytes from which they further disseminate hematogeneously to the brain and elsewhere. The physiological path inside the organism, as well as the mechanism that the bacterium employs to enter the cell, escape from the phagocytic vacuole, and spread from one cell to another through actin-based motility are all summarized in Figure 1 and 2.

The non-phagocytic bacterial entry is mediated by at least two factors: Internalin A (InlA) and B (InlB). The first step occurs in non-phagocytic cells such us epithelial cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis and that is why this bacterium can spread through epithelial barriers. Exit from the vacuole requires expression of Listeriolysin O (LLO), a pore-forming toxin which in some cells can function synergistically with or be replaced by a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC). The pore-forming activity of extracellular LLO leads to internal changes in cell processes distinctives of the Listeria infection. These include changes in histone modification, deSUMOylating, mitochondrial fission, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lysosomal permeabilization (13). The vacuole escape happens more often than the transcytosis process, and lysis of the two- membrane vacuole is performed by Lecithinase A (PlcA) and B (PlcB). On the other hand, in goblet cells, it can transcytose across the cell within a vacuole, and in some macrophages, it can replicate in spacious Listeria-containing phagosomes (SLAPs) (14). The majority of genes coding for these virulence factors are clustered in the PrfA regulon, located on 10 kb region of the bacterial chromosome. The PrfA regulon takes its name because all known virulence genes are under the either absolute or partial control of a pleiotropic activator protein PrfA (14). This cluster is represented in Figure 2 and the structure of the PrfA transcript is shown in Figure 3. Upon vacuolar escape, the intracellular movement of the bacteria requires expression of actin assembly-inducing protein (ActA) and polymerization of actin. This molecule enables the actin-based motility which is the way the aggressor can spread from cell to cell.

The activity of potent virulence factors causes a plethora of effects in the infected mammalian cell. Goblet cells are simple columnar epithelial cells that secrete gel-forming mucins, like mucin MUC5AC (15). In this cells Listeria nuclear targeted protein A (LntA) interacts with the Bromo adjacent homology domain-containing 1 protein (BAHD1) complex and induces deacetylation in histone 3 at lysine 18, leading to changes in chromatin packing. This modification is going to alter downstream gene expression. Furthermore, infection also leads to DNA damage. The host cell way to fight against Listeria infection is by upregulating several antibacterial effectors, for example, ISG15, which is the main actor of the ISGylation process that is based on a covalent modification of ER and Golgi proteins which modulate expression of cytokines IL6 and IL8 (16).

3. Relevant risk factors

Hormonal environment during the process of pregnancy creates a local suppression of CMI at the maternal foetal interface (17). Therefore, LM can reach the fetus from the maternal blood by the placenta. LM can also infect the baby during delivery or through a nosocomial transmission (18). The sign and symptoms of this infection include disseminated granulomatous lesions with micro abscesses (19) and hydrocephaly and delayed neurologic development (20). Although most cases are seen during second and third trimester, possibly, this reflects a bias where the early fetal losses caused by LM are not normally diagnosed (12). On the other hand, it is generally believed that the NS of the mother has not an increased risk of infection because of being pregnant. In fact, this has only been seen very exceptionally (21).

Elderliness has been demonstrated to be a strong risk factor to NL. This is caused by the partial loss of T-cell immunity that occurs in the process of aging. Despite this, bacteremia is more frequent since the age of 75 onwards, whereas NL appears more in the interval of 45-65 years old (22)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune condition in which healthy cells and tissues are attacked throughout the organism, and infection is one of the main causes in these patients. A report of 26 cases in Mexico with SLE (23) found that, although among SLE patients neurolisteriosis was extremely rare (0,53-2,25%), its clinical presentation is unspecific, and its diagnosis can be easily mistaken with a neuropsiquiatric lupus outbreak. LM is actually one of the top three pathogens causing CNS infections in SLE patients (24). There is not enough evidence, however, to confirm if SLE increases the risk of LM infection, but it is clear that it worsens its prognosis. Studies (25)indicate that early diagnosis from blood and tissue cultures determine the effectiveness and success of the future treatment.

In a prospective study of 16 million people in the Netherlands (25) they found that of all bacterial meningitis among diabetic patients over 6% were caused by LM, and that these patients were at a 2-fold higher risk of developing meningitis, due to an impaired cell-mediated immunity with decreased efficacy of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes, and T-lymphocytes.

Other case report (26) finds the development of rhombencephalitis after a Listeria infection, in which the patient medical history included hypertension, type II diabetes and more importantly cryptogenic cirrhosis. As in almost every other case report, they outline the importance of an early diagnosis for future antibiotic treatment and an urgent MR brain scan for patients with progressive disabling brainstem signs.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) by itself is not considered a risk factor for developing neurolisteriosis but its treatment includes alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody that causes a massive CD8+ T-cell depletion, which may enhance LM replication after infection (27). So far, very few cases of MS patients under alemtuzumab treatment were reported to develop neurolisteriosis, but it is believed by the authors that these cases might be heavily underrepresented. For all this it is especially important to follow closely in MS patients the outbreak of LM infections, because most of them might be healthy carriers before alemtuzumab treatment, as they developed the disease in a matter of hours after administration. In these cases, the best option is believed to be an antibiotic prophylactic treatment.

The MONALISA study (2) found that patients with neurolisteriosis treated with adjuvant corticoids had a worse outcome in comparison with patient without corticotherapy. As explained before, LM is an intracellular facultative bacterium. Therefore, a suppression or decrease in the CMI is going to facilitate its dissemination and neuroinvasion. According to the MONALISA study, statistically the most frequent comorbidities which increase the chance of developing neurolisteriosis are solid organ cancer and diabetes mellitus.

In this study they also describe all the possible immunosuppressive causes for NL which are: daily alcohol intake (which stands for more than three drinks per day), cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, solid organ cancer, hematological neoplasias, hematopoietic stem- cell transplantation, solid organ transplantation, asplenia, pre- existing neutropenia, pre-existing lymphopenia, HIV infection, inflammatory bowel diseases, inflammatory rheumatic disorders, other autoimmune diseases and congenital immune deficiency (2).

4. Conclusions

This review is a study with certain limitations. When speaking about risk factors for bacterial infections, there are many that are common to different infections in different parts of the body. Since our work is focused on the risk factors of Neurolisteriosis, there are not many papers that gather such specific data, and they tend to focus either on more diverse symptomatology or even other infections caused by other bacteria.

There is a series of risk factors such as alcoholism, diabetes, bad nutritional habits, etc. that are general for listeriosis. Therefore, we decided not to analyse all of them and focus exclusively on the risk factors specific for Neurolisteriosis. It is important to clarify that in this sense, the literature review is neither complete nor perfect. It could be improved by doing a meta-analysis of all the risk factors related to listeriosis and not only those exclusive to CNS impairments.

However, the future of Neurolisteriosis research is promising as there is still much information to be extracted from a typical LM infection in the Central Nervous System. As a matter of fact, our work has evidenced an increased trend of investigation within this field of study, and as more clinical cases keep being published the better understanding of this disease the scientific community will have. Hence, this review could help future researchers to more easily organize the information gathered on Listeria monocytogenes and the risk factors associated with its neuronal infection.

Neuroinvasion due to L. monocytogenes can cause several forms of encephalitis and meningitis with diverse clinical manifestations, and as of today LM remains an important public health issue, particularly in the elderly, infants, immunosuppressed, and those with malignancies that may influence in any way the immune system function. For patients with a clinical diagnosis of rhombencephalitis and acute bacterial meningitis, recognition of the symptoms caused by listerial infection plays a vital role in allowing early diagnosis, treatment and ensures an optimal patient outcome without neurologic sequelae.

Since LM is only sensitive to certain antibiotics, it is important to perform an early microbiological diagnosis that confirms the infectino. LM is difficult to isolate from the CSF but not so much from blood or other infected tissues. In addition to the microbiological diagnosis, MR imaging is extremely important in demonstrating the predilection of the listerial infection for the brain stem and cerebellum.

As it has been previously explained, several scenarios exist where this infection can be considerably more dangerous and pose a life-threatening situation to the patient. In pregnant women diagnosis and detailed treatment tracing by doctors is essential, as it is at risk not only the life of the woman but also the foetus, with the additional complications a miscarriage or stillbirth may cause. Other than that, patients with impairedimmune system can exist due to a wide variety of factors. Immunosuppressive treatments such as corticosteroids or monoclonal antibodies can worsen the course of a pre- existing or novel infection, and in these cases an antibiotic prophylactic treatment is of urgent need following an early diagnosis. Autoimmune conditions such as Lupus Erythematosus are also among the list of risk factors that can influence the development of neuroinvasive situations by LM, with very unspecific symptomatology.

For all of the exposed above, among these patients an early diagnosis is even more relevant and can change the course of infection. Precise evaluation of symptomatology and continuous monitoring should be always performed. The CSF in listerial infection typically reveals an increased leukocyte count, usually with the predominance of polymorphonuclear cells, increased protein, and normal glucose levels. Moreover, although it is complicated, increased and improved cell culture methods should be developed to confirm LM presence, especially in CSF. And lastly, antibiotic prophylactic treatment should be considered when patients are suspects of being healthy carriers.

Statements

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge teachers Pablo Redruello Guerrero, Mario Rivera Izquierdo and Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos-Bossini for their help to conduct the present studies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None

Abbreviations

- Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

- Actin assembly-inducing protein (ActA)

- Bromo adjacent homology domain-containing 1 protein (BAHD1)

- Cell-mediated immunity (CMI)

- Central Nervous System (CNS)

- Cerebro Spinal Fluid (CSF)

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

- Interleukin 6 (IL6)

- Interleukin 8 (IL8)

- Internalin A (InlA)

- Internalin B (InlB)

- Lecithinase A (PlcA) and B (PlcB)

- Listeria nuclear targeted protein A (LntA)

- Listeria monocytogenes (LM)

- Listeriolysin O (LLO)

- Magnetic Resonance (MR)

- Mucin 5AC gene (MUC5AC)

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Neural System (NS)

- Neurolisteriosis (NL)

- Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC)

- Transcription Factors (TFs)

References

1. Hedberg Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States (Response). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(7):1338–1338.

2. Charlier C, Perrodeau É, Leclercq A, Cazenave B, Pilmis B, Henry B, et Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017;17(5):510–9.

3. Walland J, Lauper J, Frey J, Imhof R, Stephan R, Seuberlich T, et Listeria monocytogenes infection in ruminants: Is there a link to the environment, food and human health? A review. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2015;157(6):319–28.

4. Schlech New perspectives on the gastrointestinal mode of transmission in invasive Listeria monocytogenes infection. Clinical and investigative medicine Medecine clinique et experimentale. 1984;7(4):321–4.

5. Lecuit M. <scp> Listeria monocytogenes </scp> , a model in infection biology. Cellular Microbiology. 2020;22(4).

6. Thomas J, Govender N, McCarthy KM, Erasmus LK, Doyle TJ, Allam M, et al. Outbreak of Listeriosis in South Africa Associated with Processed Meat. New England Journal of 2020;382(7):632–43.

7. de Noordhout CM, Devleesschauwer B, Angulo FJ, Verbeke G, Haagsma J, Kirk M, et al. The global burden of listeriosis: a systematic review and meta- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014; 14(11):1073–82.

8. Callapina M, Kretschmar M, Dietz A, Mosbach C, Hof H, Nichterlein Systemic and Intracerebral Infections of Mice with Listeria monocytogenes Successfully Treated with Linezolid. Journal of Chemotherapy. 2001;13(3):265–9.

9. Arslan F, Meynet E, Sunbul M, Sipahi OR, Kurtaran B, Kaya S, et al. The clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of neuroinvasive listeriosis: a multinational European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2015;34(6):1213–21.

10. Drevets DA, Leenen PJM, Greenfield RA. Invasion of the central nervous system by intracellular Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):323–47.

11. Clauss HE, Lorber Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2008 Jul 11;10(4):300–6.

12. Charlier C, Disson O, Lecuit M. Maternal-neonatal Virulence. 2020;11(1):391–7.

13. Cossart P, Lecuit Interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells during entry and actin-based movement: bacterial factors, cellular ligands and signaling. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(14):3797–806.

14. Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2018;16(1):32–46.

15. Ma J, Rubin BK, Voynow JA. Mucins, Mucus, and Goblet Chest. 2018;154(1):169–76.

16. Krypotou E, Scortti M, Grundström C, Oelker M, Luisi BF, Sauer-Eriksson AE, et Control of Bacterial Virulence through the Peptide Signature of the Habitat. Cell Reports. 2019;26(7):1815-1827.e5.

17. Sappenfield E, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP. Pregnancy and Susceptibility to Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and 2013;2013:1–8.

18. MYLONAKIS E, PALIOU M, HOHMANN EL, CALDERWOOD SB, WING EJ. Listeriosis During Medicine. 2002;81(4):260–9.

19. Janakiraman V. Listeriosis in pregnancy: diagnosis, treatment, and Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):179–85.

20. Curcio AM, Shekhawat P, Reynolds AS, Thakur Neurologic infections during pregnancy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;172:79–104.

21. Adriani KS, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Bacterial meningitis in pregnancy: report of six cases and review of the Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(4):345–51.

22. Ricci A, Allende A, Bolton D, Chemaly M, Davies R, Fernández Escámez PS, et Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready‐to‐eat foods and the risk for human health in the EU. EFSA Journal. 2018;16(1).

23. Horta-Baas G, Guerrero-Soto O, Barile-Fabris Central nervous system infection by Listeria monocytogenes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of 26 cases, including the report of a new case. Reumatologia clinica. 9(6):340– 7.

24. Hung J-J, Ou L-S, Lee W-I, Huang J-L. Central nervous system infections in patients with systemic lupus J Rheumatol. 2005;32(1):40–3.

25. van Veen KEB, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Bacterial meningitis in diabetes patients: a population-based prospective Sci Rep. 2016;6:36996.

26. Carrillo-Esper R, Carrillo-Cordova LD, Espinoza de los Monteros-Estrada I, Rosales-Gutiérrez AO, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez Rhombencephalitis by Listeria monocytogenes in a cirrhotic patient: a case report and literature review. Ann Hepatol. 12(5):830– 3.

27. Mazzitelli M, Barone S, Greco G, Serapide F, Valentino P, Giancotti A, et al. Listeria infection after treatment with alemtuzumab: a case report and literature review. Would antibiotic prophylaxis be considered? Infez Med. 2020;28(2):258–62.

AMU 2022. Volumen 4, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

23/03/2022 04/04/2022 31/05/2022

Cita el artículo: Ramos Cela M, Medina Martínez AJ, Vera Martín I. Infection of Listeria monocytogenes associated to the Central Nervous System: cell pathogenesis, diagnosis and risk factors. AMU. 2022; 4(1): 40-56