Laura Mariana Amador-Castilla 1; Joaquín Javier Camacho-Tapia 1; María Esperanza Romero-Barrionuevo 1

1 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Graciela Isabel Piedra-Molina 2; Andrea Moreira-Piñero 2; Ana Rodríguez-Martín 2; Antonio Moral-Pulido 2; María Leonés-Alonso 2; Marta Mozola 2

2 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

El SARS-CoV-2 es un virus que provoca la enfermedad por coronavirus 19, también denominada COVID-19. En Europa han fallecido más de 900 000 personas debido a esta enfermedad desde el inicio de la pandemia. El objetivo de esta revisión narrativa es analizar la repercusión de la pandemia sobre la salud mental de los médicos y enfermeros en Europa. Los factores de riesgo estudiados fueron: ser joven, ser mujer, no contar con el equipo de protección adecuado y el miedo al contagio y a transmitirlo a familiares, pacientes y compañeros.

Los factores protectores más frecuentes fueron contar con un equipo de protección adecuado, conocer protocolos para combatir la COVID-19 e informarse sobre dicha enfermedad. En general, se ha producido un incremento de ansiedad, estrés, insomnio, depresión e, incluso, de ideación suicida.

En cuanto a los médicos, destacaron efectos negativos como la culpabilidad, la confusión y el agotamiento. Sin embargo, el reconocimiento de su labor por el público general fue muy positivo. Respecto a los enfermeros, varios estudios consideraron que habrían sufrido más que los médicos durante la pandemia por tener un trato más directo con los pacientes. Sin embargo, el mayor esfuerzo por cuidar a sus pacientes incrementó su satisfacción por compasión más que entre los médicos.

La pandemia por COVID-19 ha supuesto un desafío para el sistema asistencial. El estrés y la difícil toma de decisiones en situaciones extremas han repercutido negativamente en la salud mental de médicos y enfermeros. Por ello, se recomienda el establecimiento de medidas que aboguen por su salud mental.

El resultado obtenido concuerda mayoritariamente con un impacto negativo en la salud mental de médicos y enfermeros, que debe ser tratado con una mayor naturalidad en estos colectivos, lo que beneficiaría también a los pacientes, pues recibirían cuidados de mayor calidad.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, salud mental, médicos, enfermeros, efectos, factores de riesgo.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, doctors, nurses, effects, risk factors.

Introducción

El SARS-CoV-2 se identificó por primera vez en diciembre de 2019 en Wuhan (China). Este virus provoca en humanos la enfermedad por coronavirus 19, la COVID-19. Debido a su fácil transmisión y la falta de conocimiento, se propagó rápidamente. Apenas tres meses más tarde, el 11 de marzo de 2020, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) declaró la situación de pandemia (1). Asimismo, el incremento exponencial de casos en Europa situó a este continente como nuevo epicentro del virus.

En Europa, desde el inicio de la pandemia, han fallecido 920.952 personas hasta el día 25 de marzo de 2021 (2). El coronavirus ha generado múltiples consecuencias, como son las crisis económica, social y mental, mientras que los casos fueron aumentando hasta sobrecargar el sistema sanitario. La mayoría de las medidas para disminuir el contagio han ido enfocadas al distanciamiento social. Como consecuencia de este distanciamiento, se ha producido una deshumanización de las relaciones sociales con las posibles consecuencias mentales que ello puede suponer (3).

El objetivo de esta revisión narrativa es estudiar la repercusión mental de la pandemia en médicos y enfermeros y profundizar en los factores que han marcado la diferencia para poder potenciarlos y favorecer la buena salud mental del personal sanitario y, por ende, un mejor cuidado de sus pacientes.

Factores generales que afectan a la salud mental

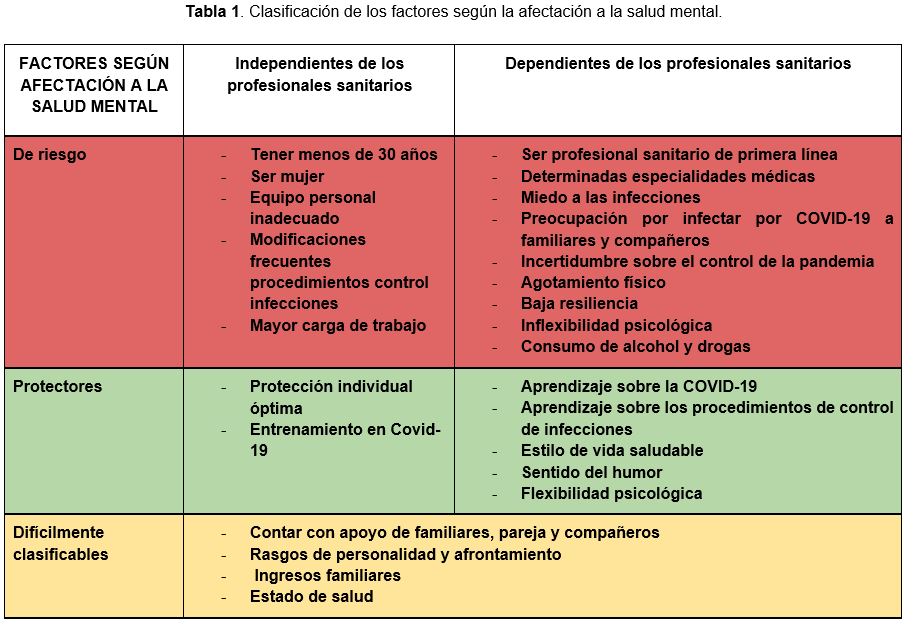

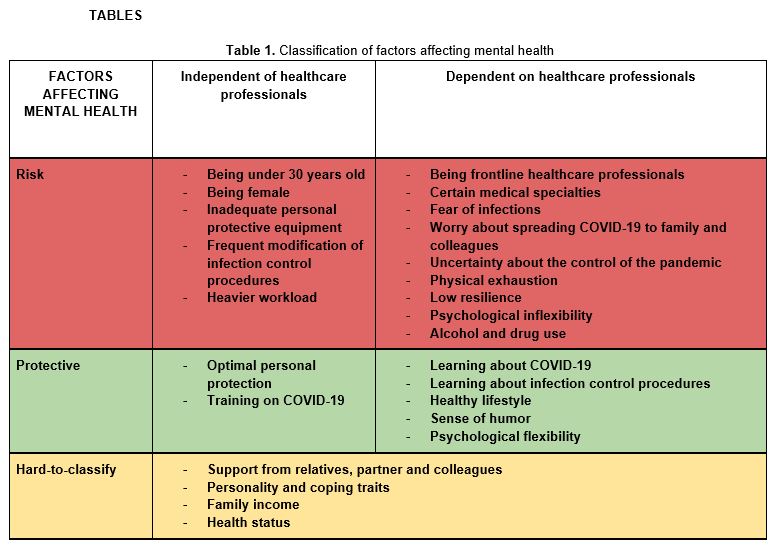

Varios estudios identificaron factores relacionados con la afectación en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios por la pandemia por COVID-19. Su amplia variedad obligó a clasificarlos. (Tabla I) A continuación, se propone la siguiente clasificación basada en dos criterios: “de riesgo/protectores”, que afectan negativa y positivamente de forma respectiva; y “dependientes/independientes” de los profesionales sanitarios. Se entiende que un factor es independiente cuando se encuentra fuera del control de la persona a la que afecta y dependiente cuando el factor está determinado por las preferencias o cualidades de la persona. Durante el análisis y la categorización se hallaron rasgos que no podían clasificarse claramente. Para estos factores se creó una categoría intermedia denominada “factores difícilmente clasificables”.

En primer lugar, los factores de riesgo categorizados como independientes fueron: ser joven, especialmente menor de treinta años (4–7); ser mujer (8–10); no contar con un equipo personal de protección adecuado (9, 11); dificultad para mantenerse actualizados a causa de las modificaciones frecuentes en los procedimientos de control de infecciones (3, 12) y la mayor carga de trabajo por la pandemia (9, 11).

En segundo lugar, los factores protectores considerados independientes fueron: contar con un equipo de protección individual óptimo y recibir entrenamiento sobre protocolos para combatir la COVID-19 (4, 13).

En tercer lugar, se examinan los factores de riesgo clasificados como dependientes: ocupar un puesto de trabajo en primera línea (5); dedicarse a determinadas especialidades médicas (14), como la psiquiatría (6), obstetricia, ginecología y traumatología (12, 15); la preocupación por infectarse y, en especial, de infectar a sus familiares, compañeros o pacientes (3, 16); la incertidumbre sobre cuándo y cómo se controlará la pandemia (3); el agotamiento físico por la gran carga de trabajo (9, 11); la inflexibilidad psicológica; una baja resiliencia para afrontar las consecuencias de sus acciones (6) y el consumo de alcohol y otras drogas (3), aunque un estudio afirma que fue la estrategia de afrontamiento menos utilizada (13).

En cuarto y último lugar, se encuentran los factores protectores dependientes, más personales: aprender sobre la COVID-19 y los procedimientos de control de infecciones por cuenta propia (3) y tener un estilo de vida saludable, sentido del humor y flexibilidad psicológica (6).

La afectación de la salud mental también estaba influenciada por factores más difíciles de clasificar, como el apoyo de familiares, pareja, amigos y compañeros de trabajo (17), los ingresos familiares, el propio estado de salud y los rasgos de personalidad y afrontamiento (18, 19).

Efectos generales sobre la salud mental de médicos y enfermeros

La rápida evolución de la pandemia y la incertidumbre generaron una situación de gran inquietud tanto en la población general como en el personal sanitario. Según estudios llevados a cabo en anteriores pandemias como la del SARS, el descubrimiento de una enfermedad potencialmente mortal podría generar un aumento sobre la presión mental con consecuencias físicas y psicológicas (8). Para que la información recogida sea lo más objetiva posible, los estudios incluyen frecuentemente escalas como la COVID Anxiety Scale o CAS, la Brief Resilience Scale o BRS y el Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation-YP (CORE-YP) (20).

La mayor parte de los médicos tenían miedo a enfermar y a sus consecuencias, como infectar a compañeros, padecer secuelas clínicas de la COVID-19, tener que someterse a confinamiento o encontrar dificultades al reincorporarse al entorno de trabajo (16). No obstante, estos riesgos eran considerados con resignación como parte de su trabajo (9). El temor a infectar de SARS-CoV-2 a familiares se asocia con un incremento de ansiedad, estrés, insomnio y depresión (8, 10, 21, 22). Otros factores, como la facilidad de transmisión del virus (22–24), su gran virulencia (22, 25) y su elevada morbimortalidad incrementan el miedo, la ansiedad e, incluso, ataques de pánico (22, 26–28). Además, la incertidumbre también está influyendo negativamente en la salud mental (3).

El efecto psicológico se ha visto reflejado incluso en países con cifras relativamente bajas de COVID-19 (4). Las repercusiones más observadas son depresión, ansiedad y estrés (3, 18). En un meta-análisis que abarca datos de 33.062 personas, se obtuvo como resultado una prevalencia de 22,8 %, 23,2 %, y 38,9 % correspondientes a depresión, ansiedad e insomnio en países afectados por la COVID-19 (29). Igualmente, esto se vio reflejado en un estudio llevado a cabo en el Hospital General de Nasice (Croacia): un 11 % del personal sanitario presentaba depresión de moderada a muy severa y lo mismo pasaba con el estrés en un 10 % de ellos (30). No obstante, es importante considerar que la mayoría de los estudios que evaluaron alteraciones mentales se llevaron a cabo a través de Internet y se podría estar sobreestimando la prevalencia de alguna de estas. Esta afirmación se basa en que los individuos que más padecen estos trastornos (depresión, ansiedad, síndrome de burn-out) son frecuentemente los que más se interesan en responder los cuestionarios (5, 31). También es interesante profundizar en la ideación suicida. En un estudio realizado en Chipre en mayo de 2020, se observó que el 6 % del personal sanitario presentaba ideas de suicidio (4). Del mismo modo, otro estudio realizado en China reflejó un porcentaje similar al anterior, de 8817 profesionales sanitarios un 6,5 % dieron señales de ideación suicida o autolesión (32). Otro aspecto que ha influido ha sido el desarrollo tecnológico. La población y, por ende, los profesionales sanitarios, utilizan cada vez más las redes sociales. El incremento del uso de las redes sociales, junto con la infodemia, ha provocado mayor sensación de ansiedad y preocupación, lo que repercute negativamente en el bienestar mental (33).

El personal sanitario que ha estado en primera línea contra la COVID-19 presenta en general un incremento de síntomas de depresión y estrés postraumático (10, 21, 22). Estos han estado sometidos a una gran responsabilidad en situaciones extremas y a largas jornadas laborales (22). De la misma forma, en un estudio llevado a cabo en España se observó una relación entre los territorios más afectados por la pandemia y la prevalencia de alteraciones mentales. En función del número de muertes por día y la etapa de la evolución de la COVID-19, variaba el bienestar psíquico del personal sanitario (17, 18). Durante la fase de impacto, la subida de la onda epidémica del nuevo brote, el nivel de estrés es menor incluso que el observado en la fase de desilusión. La capacidad para hacer frente a nuevas ondas epidémicas disminuirá si no hay tiempo suficiente para la recuperación psicológica (20). La exposición a retos, como es la COVID-19, si bien es cierto que saca lo mejor del profesional, también genera un posterior desgaste y agotamiento. Además, el estrés dificulta la sensación de satisfacción por el trabajo desempeñado (34). Por ello, es importante contemplar medidas que potencien la recuperación de los profesionales sanitarios, para poder afrontar un nuevo brote, si lo hubiese, con la mayor fuerza posible (20).

No obstante, la valoración por parte de la población a los trabajadores sanitarios ha amortiguado en parte los efectos psicológicos de la pandemia, ya que ha generado una sensación de autoeficacia y refuerzo positivo (8). Una de las medidas de protección de la salud mental más utilizadas por médicos y enfermeros ha sido el humor, lo que ha disminuido el impacto negativo de la pandemia (3, 6). Igualmente, hacer que las personas recuerden a sus seres queridos y los pensamientos profesionales positivos, como la sensación de que uno puede ser útil en la batalla contra el virus, pueden resultar beneficiosos para el bienestar emocional y, por tanto, hacer más llevadero el estrés (7, 17).

También es interesante destacar que aquellos que previamente habían manifestado problemas psicológicos tienen un riesgo incrementado en situaciones extremas como la pandemia. Por ello, es importante la detección precoz de problemas psicológicos para identificar a los individuos con mayor riesgo y poder actuar a tiempo (9). De hecho, en un estudio llevado a cabo en Bélgica, se observó que entre el 18 % y el 27 % del personal había necesitado ayuda psicológica profesional durante la pandemia (17).

Aunque la mayoría de la información recogida defiende que la pandemia originada por el SARS-CoV-2 ha influido negativamente en la salud mental de los profesionales de la salud, también hay publicados una minoría de estudios que defienden lo contrario. En un estudio realizado en China, se observó que la frecuencia de desgaste y agotamiento era menor en los profesionales sanitarios dedicados al COVID-19 que en aquellos dedicados al resto de áreas (8, 35). Asimismo, otro estudio realizado en Alemania concluyó que estos profesionales presentaban menores tasas de ansiedad y depresión porque contaban con más información que la población sobre la COVID-19 (20).

Se han observado una serie de parámetros que hacen interesante el análisis pormenorizado de las diferencias en repercusión psicológica entre ambos sexos. Varios estudios señalan que la prevalencia de estrés postraumático en mujeres es mayor que en varones. De hecho, se estima entre el doble y el triple de probabilidad de padecer estrés postraumático en ellas (8, 10, 36–39). Se ha reflexionado sobre la influencia de la pareja en la fortaleza mental de la mujer. La mujer per se es más propensa a padecer síntomas de depresión, pero aquellas que están solteras parecen tener mayor riesgo de sufrir este tipo de trastornos (10, 40–42). La edad no parece ser determinante, pero el grupo de 30-49 años es en el que mayor impacto en el bienestar mental se ha encontrado (10, 17, 36). En general, las mujeres, y sobre todo aquellas que trabajan en unidades en contacto con la COVID-19 o en UCI, han presentado mayor frecuencia de sintomatología y trastornos de salud mental (9).

- Efectos sobre médicos

Los médicos son uno de los colectivos que más se han implicado en la batalla contra la pandemia. De hecho, la sociedad ha mostrado su agradecimiento en redes sociales y han aplaudido en los balcones. El hecho de sentirse más valorados ha afectado positivamente a su salud mental (8, 35), y les ha ayudado a sufrir menos (8).

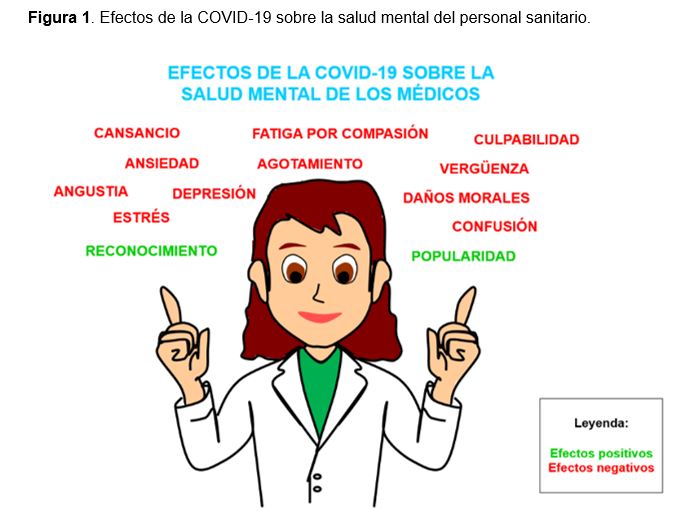

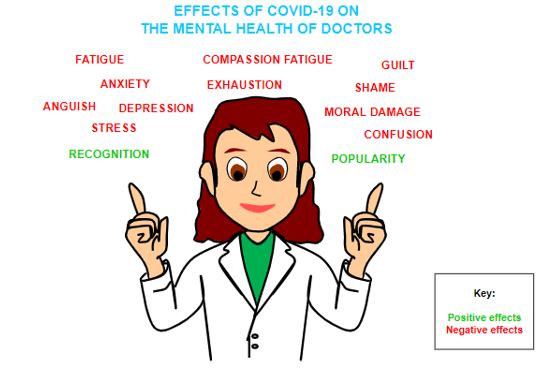

A pesar de ello, la avalancha de factores y estímulos nuevos y negativos han sido causa de otras muchas reacciones adversas (Figura 1). El SARS-CoV-2 es un virus tan desconocido que ha obligado a los médicos a someterse a una actualización continua. Se ven regularmente abocados a renovar periódicamente sus protocolos, sus guías de actuación, sus normas o sus conocimientos acerca del coronavirus, lo que les confunde y agota. Por ello, sería recomendable la disponibilidad de una fuente de información más sencilla que les proporcione mayor seguridad y estabilidad (12). Además, las difíciles circunstancias a las que han tenido que hacer frente los han llevado a la tesitura de tomar decisiones que pudiesen ir en contra de sus principios éticos, generando importantes daños morales (34, 43), vergüenza y culpabilidad (34, 44), o agotamiento y fatiga por compasión (34, 45). Según un estudio realizado por la BMA (British Medical Association) entre médicos a lo largo de la pandemia, durante este período aparecieron o, incluso, empeoraron entre ellos síntomas de depresión, ansiedad, estrés, cansancio o angustia debido a la densa carga a la que se vieron sometidos (12, 46).

Para analizar las consecuencias, los estudios se enfocaron en las distintas especialidades de la Medicina. Por un lado, aseguraron que estar en la primera línea de batalla o en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos constituyó un importante factor de riesgo para padecer ansiedad, aunque no depresión (8). Por otro lado, en el caso de los obstetras y los ginecólogos, se concretó que aumentó entre ellos la prevalencia de ansiedad y depresión en el tiempo de la pandemia (12). Además, una encuesta realizada a médicos internistas en España en contacto con la COVID-19 apunta que un 40 % presentaban rasgos compatibles con el síndrome de burn out. Este síndrome se asocia a ansiedad, depresión, abuso de determinadas sustancias o aparición de síntomas psicosomáticos (31). En el caso de los psiquiatras, investigaciones anteriores señalan que están expuestos a una serie de factores estresantes únicos que pueden aumentar su riesgo de deterioro de la salud mental (6). Además, en un estudio medido con la escala CAS, se observó que los psiquiatras presentan menor ansiedad que médicos de otras especialidades. Más allá, también se diferenciaban en su forma de afrontar la pandemia. Los psiquiatras se mostraron más reacios a considerar que la sobreinformación era efectiva. A su vez, eran más propensos a usar sedantes o medicamentos (6). A pesar de que la mayoría sostiene lo contrario, un estudio llevado a cabo en el Hospital Universitario de Augsburgo sostiene que los médicos no notaron diferencias en su salud mental en función del contacto mantenido con pacientes COVID (20).

Aparte de los efectos y la especialidad de los doctores, es interesante y necesario poner el foco en otro tema muy vinculado a éste: la salud mental de los médicos sigue siendo un tabú para ellos. Muy pocos son capaces de abrirse y compartir su situación. Esto se produce por el temor a cómo reaccionarán los demás y a su posible discriminación, lo que impide que busquen el apoyo y el asesoramiento necesarios (12, 47).

- Efectos sobre enfermeros

A continuación, se procedió a analizar las repercusiones de la pandemia en la salud mental de los enfermeros. Múltiples estudios apuntan que la salud mental de este sector, cuya labor ha demostrado ser esencial, se está viendo afectada bastante. El estrés originado por la pandemia está generando un aumento en la prevalencia de cuadros de ansiedad (20, 48–50). Algunos estudios sostienen que esta podría incluso haberse duplicado (8, 37). Los profesionales de enfermería, además, presentan más cuadros de frustración y depresión a causa del estrés (8, 48). De hecho, algunos autores afirman que incluso más que los médicos (4, 22).

Investigadores de países muy afectados por la COVID-19, como Alemania, y de países menos afectados, como Chipre, coinciden en que los enfermeros resultaron más afectados psicológicamente que los médicos. Presentan síntomas que van desde la ansiedad, frustración y depresión ya mencionadas a mayor exhaustividad, desencanto y síndrome postraumático. Estudios realizados en ambos países proponen como posible causa el contacto más directo y prolongado de estos sanitarios con los pacientes (4, 20). Sin embargo, un contacto más estrecho con los pacientes no ha demostrado ser siempre negativo. Un estudio realizado en Andalucía (España) señala que el reconocimiento por la población y el mayor esfuerzo por sus pacientes ha aumentado la satisfacción por compasión entre los enfermeros. Esto ocurre también entre los médicos, pero en menor medida (34).

Conclusión

En esta revisión se ha recopilado y analizado la literatura sobre los efectos de la pandemia por COVID-19 en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios. Para ello, se ha prestado especial atención a los datos obtenidos en países europeos, especialmente en médicos y enfermeros.

La pandemia por COVID-19 ha llevado a los sanitarios a situaciones extremas que han afectado a la salud mental de médicos y enfermeros. El agotamiento físico por las largas jornadas laborales y los conflictos morales a los que se han enfrentado han afectado a su salud mental. La exposición a retos suele sacar lo mejor de estos profesionales, pero, en demasía, genera estrés, desgaste y agotamiento, como se ha reflejado a lo largo del estudio. Esto no sólo es perjudicial para ellos, pues el agotamiento médico se ha relacionado con errores médicos y otros efectos dañinos para compañeros de trabajo, pacientes y todo el sistema de atención médica (3).

Un factor protector muy efectivo es el apoyo de familiares, amigos y de la población general, que suponen un refuerzo positivo y les proporciona sensación de autoeficacia. Sin embargo, es preocupante la cantidad de factores de riesgo fuera del control de médicos y enfermeros. Además, la detección precoz de problemas psicológicos permite identificar a los individuos con mayor riesgo y poder actuar a tiempo (9). Por ello, sería muy recomendable destinar esfuerzos a la prevención de alteraciones de la salud mental y superar así el tabú que aún las envuelve. Preservar el bienestar de los profesionales sanitarios es ahora más importante que nunca. Ayudarlos les permitirá ofrecer en el futuro una mejor atención y un mejor cuidado a sus pacientes.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- COVID-19: cronología de la actuación de la OMS [Internet].World Health Organization; 2021. [citado: 6 marzo 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19

- COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of week 11, updated 25 March 2021 [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2021. [citado: 26 marzo 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

- Hummel S, Oetjen N, Du J, Posenato E, Resende de Almeida RM, Losada R, et al. Mental Health Among Medical Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Eight European Countries: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e24983.

- Chatzittofis A, Karanikola M, Michailidou K, Constantinidou A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1435.

- Torrente M, Sousa PA, Sánchez-Ramos A, Pimentao J, Royuela A, Franco F, et al. To burn-out or not to burn-out: a cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044945.

- Jokić-Begić N, Lauri Korajlija A, Begić D. Mental Health of Psychiatrists and Physicians of Other Specialties in Early COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk ind Protective Factors. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(3-4):536-48.

- Haravuori H, Junttila K, Haapa T, Tuisku K, Kujala A, Rosenström T, et al. Personnel Well-Being in the Helsinki University Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7905.

- Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell’Oste V, et al. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6180.

- Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, Porru S, Carta A, Tardivo S, Bovo C, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;30:e1.

- Di Tella M, Romeo A, Benfante A, Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(6):1583-7.

- Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A, Arango C, Moreno C, Ferre F, et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48-57.

- Shah N, Raheem A, Sideris M, Velauthar L, Saeed F. Mental health amongst obstetrics and gynaecology doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a UK-wide study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:90-4.

- Vallée M, Kutchukian S, Pradère B, Verdier E, Durbant È, Ramlugun D, et al. Prospective and observational study of COVID-19’s impact on mental health and training of young surgeons in France. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):e486-8.

- Dimitriu MCT, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda AC, Nica AA, Carap AC, Constantin VD, et al. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109972.

- Thakrar A, Raheem A, Chui K, Karam E, Wickramarachchi L, Chin K. Trauma and orthopaedic team members’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(6):316-25.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna M del C, Martínez-Diz S, Fernández-García MÁ, Martín-Romero DT, Maldonado-Rodríguez F, et al. Clinical Factors, Preventive Behaviours and Temporal Outcomes Associated with COVID-19 Infection in Health Professionals at a Spanish Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4305.

- Vanhaecht K, Seys D, Bruyneel L, Cox B, Kaesemans G, Cloet M, et al. COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2021;33(1):mzaa158.

- Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Mula A, Martin-Delgado J, Pérez-Jover MV, et al. Acute stress of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic evolution: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042555.

- DiGangi JA, Gomez D, Mendoza L, Jason LA, Keys CB, Koenen KC. Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(6):728-44.

- Skoda E-M, Teufel M, Stang A, Jöckel K-H, Junne F, Weismüller B, et al. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2020;42(4):688-95.

- Zhang W, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao W, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242-50.

- Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JD, Nobre CB, Pinheiro WR, de Oliveira CRT, et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112972.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-207.

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970-1.

- Wang W, Tang J, Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. abril de 2020;92(4):441-7.

- Anxiety on rise due to coronavirus, say mental health charities [Internet]. The Guardian; 2020. [citado: 26 marzo 2021]. Disponible en: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/anxiety-on-rise-due-to-coronavirus-say-mental-health-charities

- Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1439-40.

- Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2007;52(4):233-40.

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901-7.

- Salopek-Žiha D, Hlavati M, Gvozdanović Z, Gašić M, Placento H, Jakić H, et al. Differences in Distress and Coping with the COVID-19 Stressor in Nurses and Physicians. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(2):287-93.

- Macía-Rodríguez C, Alejandre de Oña Á, Martín-Iglesias D, Barrera-López L, Pérez-Sanz MT, Moreno-Diaz J, et al. Burn-out syndrome in Spanish internists during the COVID-19 outbreak and associated factors: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e042966.

- Xiaoming X, Ming A, Su H, Wo W, Jianmei C, Qi Z, et al. The psychological status of 8817 hospital workers during COVID-19 Epidemic: A cross-sectional study in Chongqing. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:555-61.

- Clavier T, Popoff B, Selim J, Beuzelin M, Roussel M, Compere V, et al. Association of Social Network Use With Increased Anxiety Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Anesthesiology, Intensive Care, and Emergency Medicine Teams: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2020;8(9):e23153.

- Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21-22):4321-30.

- Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin X, Anderson AE, et al. A Comparison of Burnout Frequency Among Oncology Physicians and Nurses Working on the Frontline and Usual Wards During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e60-5.

- Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921.

- Magnavita N, Tripepi G, Di Prinzio RR. Symptoms in Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic. A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5218

- Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, Storz KA, Reeves D, Buskirk SJ, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-27.

- Braithwaite S, Holt-Lunstad J. Romantic relationships and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:120-5.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

- Dush CMK, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2005;22(5):607-27.

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211.

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706.

- Winner J, Knight C. Beyond Burnout: Addressing System-Induced Distress. Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(5):4-7.

- Torjesen I. Covid-19: Doctors need proper mental health support, says BMA. BMJ. 2020;369:m2192.

- Zheng W. Mental health and a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:201-2.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976.

- Liang Y, Chen M, Zheng X, Liu J. Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 2020;133:110102.

- Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19 – a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci GMS E-J. 2020;18:Doc05.

Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Doctors and Nurses in Europe: An Updated Literature Review

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus that causes the coronavirus disease 2019, also known as COVID-19. Over 900,000 people have died of COVID-19 in Europe since the beginning of the pandemic. The aim of this review is to analyze the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of doctors and nurses throughout Europe.

The studied risk factors were: being young, being female, the lack of adequate protective equipment and the fear of becoming infected and transmitting the virus to relatives, patients and colleagues. The most frequent protective factors were: the access to adequate protective equipment, knowing the protocols against COVID-19 and studying the disease. In general, there was an increase in anxiety, stress, insomnia, depression and even suicidal ideation.

The most frequent negative effects observed in doctors were guilt, confusion and exhaustion. However, the social recognition of their work had a very positive influence on them. As for nurses, several studies considered that they suffered more than doctors during the pandemic due to a closer contact with patients. However, the fact that they had to make a greater effort to care for patients increased their compassion satisfaction more than among doctors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented the health care system with a challenge. Stress and difficult decision making in extreme situations have had a negative impact on the mental health of doctors and nurses. Therefore, the implementation of measures that support their mental health is recommended.

The result is mostly consistent with a negative impact on the mental health of doctors and nurses. This is an issue that should be addressed in a more natural way within these groups. This would also benefit patients, because they would receive higher quality care.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, doctors, nurses, effects, risk factors.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan (China). This virus causes COVID-19 in humans. Due to its easy transmission and the lack of knowledge about the virus, it spread rapidly. Hardly three months later, on March 11 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic (1). In addition, the exponential increase of cases in Europe led this continent to become the new epicenter of the virus.

In Europe, since the beginning of the pandemic, 920,952 people have died as of March 25 2021 (2). The coronavirus has had multiple consequences, such as the economic, social and mental crises, while the number of cases increased until the health system was overloaded. Most of the measures aimed at reducing the transmission have focused on social distancing. As a result, a dehumanization of social relations has occurred, with the possible consequences that this might lead to (3).

The aim of this review is to study the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of doctors and nurses. At the same time, it seeks to examine protective factors in order to promote them. This will encourage good mental health among healthcare workers and will therefore result in a better patient care.

General factors affecting mental health

Several studies identified factors related to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. These factors had to be classified due to their wide variety. (Table I) The following classification is proposed based on two criteria: 1) whether the factors have a negative or a positive effect (risk/protective factors) and 2) whether they are dependent on health professionals or not (dependent/independent factors). A factor is considered to be independent when it is beyond the control of the person it affects and a dependent factor is that determined by the person’s preferences or qualities. During the analysis and the categorization, some traits could not be easily classified. For these factors, an intermediate category called “hard-to-classify factors” was created.

The independent risk factors were: being young, especially under thirty years (4-7); being female (8-10); the lack of adequate personal protective equipment (9, 11); the difficulty in remaining updated due to the frequent changes in infection control procedures (3, 12); and the increased workload due to the pandemic (9, 11).

The protective factors considered independent were: having optimal personal protective equipment and receiving training on protocols to combat COVID-19 (4, 13).

The risk factors classified as dependent were: working on the frontline (5); working in certain medical specialties (14), such as psychiatry (6), obstetrics, gynecology and traumatology (12, 15); the concern about becoming infected and, in particular, about infecting relatives, colleagues or patients (3, 16); the uncertainty about when and how the pandemic will end (3); the physical exhaustion due to the heavy workload (9, 11); the psychological inflexibility; the low resilience to cope with the consequences of their actions (6); and the use of alcohol and other drugs (3), although one study states that this was the least used coping strategy (13).

The more personal, dependent protective factors were: learning about COVID-19 and the infection control procedures on one’s own (3) and having a healthy lifestyle, sense of humor and psychological flexibility (6).

Mental health was also affected by factors that are more difficult to classify, such as the support from family, partners, friends and colleagues (17), the household income, the person’s health status and the personality and coping traits (18, 19).

General effects on the mental health of doctors and nurses

The rapid evolution of the pandemic and the uncertainty generated a high level of anxiety in the population, as well as in healthcare workers. According to studies conducted in previous pandemics such as the SARS pandemic, a potentially fatal disease could increase mental stress with physical and psychological consequences (8). Previous studies often include scales such as the COVID-19 Anxiety Scale (CAS), the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and the Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation-YP (CORE-YP) to ensure that the information collected is as objective as possible (20).

Most doctors were afraid of becoming ill and its consequences, such as infecting colleagues, the clinical sequelae of COVID-19, having to confine themselves or finding difficulties to return to work (16). However, these risks were regarded with resignation as part of their job (9). The fear of infecting relatives with SARS-CoV-2 is associated with increased anxiety, stress, insomnia and depression (8, 10, 21, 22). Other factors, such as the easy transmission of the virus (22-24), its high virulence (22, 25) and its great morbimortality increased fear, anxiety and even panic attacks (22, 26-28). Moreover, uncertainty is also having a negative impact on mental health (3).

The psychological impact was present even in countries with a relatively low number of COVID-19 cases (4). The most frequently observed effects were depression, anxiety and stress (3, 18). A meta-analysis covering data from 33,062 people showed a prevalence of 22.8%, 23.2% and 38.9% of depression, anxiety and insomnia in countries affected by COVID-19 (29). This was also the result of a study performed at the General Hospital Nasice (Croatia): 11% of the healthcare professionals suffered from moderate to very severe depression and the same happened with stress to 10% of them (30). However, most of the studies assessing mental disorders were conducted online, so they might have overestimated the prevalence of some of these disorders. This is due to the fact that the individuals who suffer the most from these disorders (depression, anxiety, burnout syndrome) are often the ones who answer these questionnaires the most (5, 31).

As for suicidal ideation, a study conducted in Cyprus in May 2020 showed that 6% of the healthcare workers had suicidal thoughts (4). Another study conducted in China revealed a similar percentage: 6.5% of the 8,817 healthcare workers participating in this study showed signs of suicidal ideation or self-harm (32). Technological development also had an impact. The population, that is, healthcare workers, are increasingly using social networks. The increased use of social networks, together with the infodemic, increased the feelings of anxiety and worry, which had a negative impact on mental well-being (33).

Healthcare workers who were on the frontline against COVID-19 generally showed an increase in depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms (10, 21, 22). This is due to the great responsibility they had to bear in extreme situations and to their long working hours (22). Moreover, a study conducted in Spain also found a relationship between the regions most affected by the pandemic and the prevalence of mental disorders. The mental well-being of healthcare workers varied depending on the number of deaths per day and the stage of development of the COVID-19 (17, 18). During the impact phase—the upswing of the epidemic wave of the new outbreak—, the stress level is even lower than in the disillusionment phase. The ability to face new epidemic waves will decrease if there is not enough time for psychological recovery (20). Even though having to face challenges such as COVID-19 brings out the best of these professionals, it also causes subsequent burnout syndrome and exhaustion. In addition, stress interferes with the feeling of satisfaction for the work carried out (34). Therefore, implementing measures that enhance the recovery of healthcare professionals will enable them to deal with a new outbreak in the best possible way (20).

In addition, the social recognition of the healthcare workers reduced the psychological effects of the pandemic to a certain extent, because it provided them with a sense of self-efficacy and with positive reinforcement (8). Humor was one of the most used measures to protect mental health among doctors and nurses. This reduced the negative impact of the pandemic (3, 6). Making people remember their beloved ones, together with the positive work-related thoughts, such as a sense of usefulness in the battle against the virus, can be beneficial for the emotional well-being and therefore for coping with stress.

Those who had previously shown psychological problems are at a higher risk in extreme situations such as this pandemic. Therefore, the early detection of psychological problems is important to identify the individuals at a higher risk and to be able to act on time (9). A study conducted in Belgium showed that between 18% and 27% of the health workforce required professional psychological help during the pandemic (17).

Although most of the gathered information supports that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative influence on the mental health of healthcare workers, a few research articles claim the opposite. A study conducted in China found that burnout syndrome and exhaustion were less frequent among the healthcare workers who worked with COVID-19 patients than among those who worked in other areas (8, 35). Another study conducted in Germany revealed that these professionals presented lower anxiety and depression rates because they were more informed about COVID-19 than the rest of the population (20).

Other researchers investigated some parameters that analyze in detail the differences in the psychological impact between both sexes. Several studies indicate a higher prevalence of post-traumatic stress in women (than in men). In fact, the probability of experiencing post-traumatic stress is estimated to be between double and triple higher among women (8, 10, 36-39). The influence of their couple on the mental toughness of women has also been widely studied. Women per se are more liable to experience symptoms of depression, but single women are even more likely to develop these disorders (10, 40-42). Age does not seem to play an importantrole, but women aged between 30 and 49 experience the highest impact on their emotional well-being (10, 17, 36). In general, women, especially those who work in COVID units or in Intensive Care Units (ICU), present symptomatology and mental health disorders more frequently (9).

- Impact among doctors

Doctors are one of the social groups that have been most involved in the battle against the pandemic. In fact, society expressed appreciation for their work on social media, and people gathered at the balconies to applaud them. The fact that they felt more valued had positive effects on their mental health (8, 35) and helped them to suffer less (8).

However, the great amount of new negative factors has caused plenty of other negative impacts (Figure 1). Because SARS-CoV-2 is a new virus, doctors have to be constantly updated. Therefore, they have to regularly change their protocols, guidelines, standards or knowledge about the coronavirus. This is confusing and exhausting for them, so it is recommended to have a simpler source of information that could provide them with more security and stability (12). Moreover, the difficult circumstances they have had to face have led them to make decisions that went against their ethical principles, which resulted in significant moral damage (34, 43), shame and guilt (34, 44), or exhaustion and compassion fatigue (34, 45). According to a survey by the British Medical Association (BMA), symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, fatigue or distress appeared or even worsened among doctors during the pandemic due to the heavy burden that was placed on them (12, 46).

Figure 1. Effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers.

The studies focused on the different specialties of Medicine in order to analyze the consequences. These showed that working on the frontline or in the ICU was an important risk factor for anxiety, but not for depression (8). As for the obstetricians and gynecologists, anxiety and depression levels increased among them during the pandemic (12). In addition, a survey in Spain revealed that 40% of the internists working in direct contact with COVID-19 cases developed symptoms of burnout syndrome. This syndrome is associated with anxiety, depression, substance abuse or the development of psychosomatic symptoms (31). As for psychiatrists, previous research showed that they were already exposed to a number of unique stressors that may increase the risk of deterioration of their mental health (6). However, a study using the CAS revealed that psychiatrists were less anxious than doctors in other specialties. Moreover, psychiatrists coped with the pandemic differently, as they were more reluctant to consider over-information as an effective way of dealing with the pandemic and they were more likely to use sedatives or medication (6). Despite the fact that most studies claim the opposite, a study conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg claims that doctors did not notice changes in their mental health as a result of having direct contact with COVID-19 patients (20).

Besides their specialty and the effects they experienced, it is also important to focus on the fact that the mental health of doctors still remains a taboo. Only very few were able to open up and share their experiences due to fear of how others will react and of being stigmatized. This prevented them from seeking the appropriate support and counselling (12, 47).

- Impact on nurses

Several studies show that the mental health of nurses, whose work has proven to be essential, is suffering considerably. The stress caused by the pandemic is increasing the prevalence of anxiety symptoms (20, 48-50). Some studies claim that this prevalence could have doubled (8, 37). In addition, nursing professionals show more frustration and symptoms of depression due to stress (8, 48), even more than doctors, according to some authors (4, 22).

Researchers from countries severely affected by COVID-19, such as Germany, and from less affected countries, such as Cyprus, agreed that nurses suffered psychologically more than doctors. They showed symptoms that go from anxiety, frustration and depression to a higher level of exhaustion, disenchantment and post-traumatic stress disorder. Furthermore, two other studies suggested that these symptoms might be caused by a closer and longer contact with patients (4, 20), although this contact was not always negative. A study conducted in Andalusia (Spain) indicated that compassion satisfaction among nurses increased due to social recognition and a greater motivation for their patients. Doctors also experienced this, but to a lesser extent (34).

Conclusion

This review collects and analyzes literature about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of doctors and nurses. In order to do that, we focused on the data obtained from European countries.

Healthcare workers have faced critical situations during the COVID-19 pandemic, which have affected their mental health. They have experienced physical exhaustion due to the long working hours and the moral conflicts they have faced. Facing challenges usually brings out the best in these professionals, but in excess, it can become stressful, draining and exhausting, as seen throughout this paper. This exhaustion does not only affect healthcare workers, but it is also linked with medical errors and other harmful effects for colleagues, patients and the whole health care system (3).

Support from family, friends and the general population is a very effective protective factor, since it provides them with positive reinforcement and a sense of self-efficacy. However, the amount of risk factors over which doctors and nurses have no control is concerning. Furthermore, the early detection of psychological problems helps to identify individuals who are at higher risk in order to act promptly (9). Therefore, it is very important to focus on preventing mental health disorders and break the taboo around them. Protecting the well-being of healthcare professionals is now more important than ever. Helping these professionals will enable them to provide their patients with better care.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- COVID-19: cronología de la actuación de la OMS [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021. [Last access: 6 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19

- COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of week 11, updated 25 March 2021 [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2021. [Last access: 26 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

- Hummel S, Oetjen N, Du J, Posenato E, Resende de Almeida RM, Losada R, et al. Mental Health Among Medical Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Eight European Countries: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e24983.

- Chatzittofis A, Karanikola M, Michailidou K, Constantinidou A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1435.

- Torrente M, Sousa PA, Sánchez-Ramos A, Pimentao J, Royuela A, Franco F, et al. To burn-out or not to burn-out: a cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044945.

- Jokić-Begić N, Lauri Korajlija A, Begić D. Mental Health of Psychiatrists and Physicians of Other Specialties in Early COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk ind Protective Factors. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(3-4):536-48.

- Haravuori H, Junttila K, Haapa T, Tuisku K, Kujala A, Rosenström T, et al. Personnel Well-Being in the Helsinki University Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7905.

- Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell’Oste V, et al. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6180.

- Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, Porru S, Carta A, Tardivo S, Bovo C, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;30:e1.

- Di Tella M, Romeo A, Benfante A, Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(6):1583-7.

- Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A, Arango C, Moreno C, Ferre F, et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48-57.

- Shah N, Raheem A, Sideris M, Velauthar L, Saeed F. Mental health amongst obstetrics and gynaecology doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a UK-wide study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:90-4.

- Vallée M, Kutchukian S, Pradère B, Verdier E, Durbant È, Ramlugun D, et al. Prospective and observational study of COVID-19’s impact on mental health and training of young surgeons in France. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):e486-8.

- Dimitriu MCT, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda AC, Nica AA, Carap AC, Constantin VD, et al. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109972.

- Thakrar A, Raheem A, Chui K, Karam E, Wickramarachchi L, Chin K. Trauma and orthopaedic team members’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(6):316-25.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, Valero-Ubierna M del C, Martínez-Diz S, Fernández-García MÁ, Martín-Romero DT, Maldonado-Rodríguez F, et al. Clinical Factors, Preventive Behaviours and Temporal Outcomes Associated with COVID-19 Infection in Health Professionals at a Spanish Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4305.

- Vanhaecht K, Seys D, Bruyneel L, Cox B, Kaesemans G, Cloet M, et al. COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2021;33(1):mzaa158.

- Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Mula A, Martin-Delgado J, Pérez-Jover MV, et al. Acute stress of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic evolution: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042555.

- DiGangi JA, Gomez D, Mendoza L, Jason LA, Keys CB, Koenen KC. Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(6):728-44.

- Skoda E-M, Teufel M, Stang A, Jöckel K-H, Junne F, Weismüller B, et al. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2020;42(4):688-95.

- Zhang W, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao W, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242-50.

- Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JD, Nobre CB, Pinheiro WR, de Oliveira CRT, et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112972.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-207.

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970-1.

- Wang W, Tang J, Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. abril de 2020;92(4):441-7.

- Anxiety on rise due to coronavirus, say mental health charities [Internet]. The Guardian; 2020. [Last access: 26 March 2021]. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/anxiety-on-rise-due-to-coronavirus-say-mental-health-charities

- Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1439-40.

- Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2007;52(4):233-40.

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901-7.

- Salopek-Žiha D, Hlavati M, Gvozdanović Z, Gašić M, Placento H, Jakić H, et al. Differences in Distress and Coping with the COVID-19 Stressor in Nurses and Physicians. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(2):287-93.

- Macía-Rodríguez C, Alejandre de Oña Á, Martín-Iglesias D, Barrera-López L, Pérez-Sanz MT, Moreno-Diaz J, et al. Burn-out syndrome in Spanish internists during the COVID-19 outbreak and associated factors: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e042966.

- Xiaoming X, Ming A, Su H, Wo W, Jianmei C, Qi Z, et al. The psychological status of 8817 hospital workers during COVID-19 Epidemic: A cross-sectional study in Chongqing. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:555-61.

- Clavier T, Popoff B, Selim J, Beuzelin M, Roussel M, Compere V, et al. Association of Social Network Use With Increased Anxiety Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Anesthesiology, Intensive Care, and Emergency Medicine Teams: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2020;8(9):e23153.

- Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21-22):4321-30.

- Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin X, Anderson AE, et al. A Comparison of Burnout Frequency Among Oncology Physicians and Nurses Working on the Frontline and Usual Wards During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e60-5.

- Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921.

- Magnavita N, Tripepi G, Di Prinzio RR. Symptoms in Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic. A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5218

- Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, Storz KA, Reeves D, Buskirk SJ, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-27.

- Braithwaite S, Holt-Lunstad J. Romantic relationships and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:120-5.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

- Dush CMK, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2005;22(5):607-27.

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211.

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706.

- Winner J, Knight C. Beyond Burnout: Addressing System-Induced Distress. Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(5):4-7.

- Torjesen I. Covid-19: Doctors need proper mental health support, says BMA. BMJ. 2020;369:m2192.

- Zheng W. Mental health and a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:201-2.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976.

- Liang Y, Chen M, Zheng X, Liu J. Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 2020;133:110102.

- Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19 – a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci GMS E-J. 2020;18:Doc05.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Amador-Castilla L. M., Camacho-Tapia J. J., Romero-Barrionuevo M. E. Impacto de la COVID-19 en la salud mental de médicos y enfermeros en Europa: una revisión de la literatura actualizada AMU. 2021; 3(1):156-171