Celia Pérez-Díaz 1; Marta Miranda-García 2; Anabel González-Acedo 1

1 Máster en Investigación y Avances en Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

2 Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Marina Acién-Martín 3; Jacqueline González-del-Pino 3; Lidia Guerrero-Díaz 4; Nelly Paniagua-Becerra 5; Mª Carmen PradosCastilla 6; Andrea Sánchez-Molina 3

3 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

4 Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Málaga (UMA)

5 Lima Institute of Technical Studies (LITS)

6 Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Granada (UGR)

Cada vez es más patente la relación existente entre los disruptores endocrinos, grupo de contaminantes ambientales a los que pertenece el bisfenol A, y distintos trastornos en la salud reproductiva, como es el caso del síndrome de ovario poliquístico (SOP). En esta revisión narrativa se ha tratado de definir aspectos clave tanto del bisfenol A como del SOP, así como unificar el conocimiento actual existente entre ambos con el fin de establecer una base sólida de su relación y su repercusión en la salud. Diversos estudios señalan una posible relación no solo entre el SOP y la exposición a bisfenol A, sino también con otras enfermedades que se presentan con mayor prevalencia en mujeres con dicho síndrome, tales como alteraciones de la regulación hormonal o del metabolismo, entre otras. Sin embargo, es necesario ahondar en el conocimiento de la relación existente entre el bisfenol A y el SOP, con el objetivo de aportar una mayor evidencia. En este sentido, sería interesante el desarrollo de diferentes estudios epidemiológicos enfocados a fortalecer y reafirmar la posible asociación causal existente.

Palabras clave: bisfenol A, síndrome de ovario poliquístico, SOP, disruptor endocrino, salud reproductiva.

Keywords: bisphenol A, polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS, endocrine disruptor, reproductive health.

Introducción

Los disruptores endocrinos pertenecen a un grupo heterogéneo de moléculas (naturales o sintéticas) con la capacidad de interferir con el sistema endocrino. Esto se debe a que su estructura fenólica puede imitar a las hormonas esteroideas endógenas y antagonizar con ellas (1), causando diferentes trastornos metabólicos e incluso diversos tipos de cáncer hormonodependientes (2).

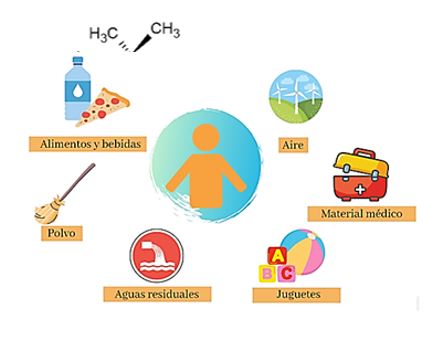

El bisfenol A es uno de los disruptores endocrinos más comunes en el medio ambiente (3) debido, fundamentalmente, al incremento en su utilización industrial en la producción de numerosos materiales sintéticos o policarbonatos, entre otros (4). Se considera un compuesto ubicuo que puede estar presente en botellas reutilizables, plásticos y metales utilizados en envases alimentarios, juguetes, equipos médicos o incluso en compuestos dentales. En esta misma línea, diversos estudios han reportado su presencia en el aire, el polvo o el agua, siendo la ingestión de agua y comida contaminada la principal ruta de exposición (5). Sin embargo, también puede producirse una absorción cutánea y a través del sistema respiratorio (6). De este modo, diferentes estudios del Centro de Control y Prevención de Enfermedades han demostrado un nivel detectable de bisfenol A en muestras de orina, líquido amniótico, tejido placentario, cordón umbilical y suero fetal (4). Este compuesto se ha llegado a detectar en el fluido folicular, lo que indica que los ovocitos estarían expuestos a este contaminante durante el proceso de la foliculogénesis (1).

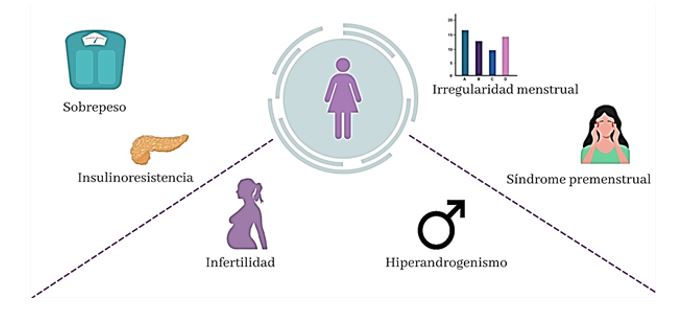

Por otro lado, el SOP se caracteriza por la presencia heterogénea de anovulación, hiperandrogenismo, morfología de ovario poliquístico, disfunción metabólica e infertilidad (7). Además de los signos y síntomas propios ya mencionados, este síndrome se relaciona con problemas sexuales y psicológicos (8). Así, aumenta la probabilidad de padecer síntomas de depresión y/o ansiedad (9).

A nivel global, es considerado el trastorno endocrino más común y heterogéneo en las mujeres en edad reproductiva (10). Su prevalencia se encuentra entre el 6 % y el 21 % dependiendo de los criterios diagnósticos (11). Además, se le atribuye más del 75 % de los casos de infertilidad anovulatoria (12).

A pesar de que la fisiopatología del síndrome no está clara, el aumento en la prevalencia de enfermedades reproductivas, la disminución de la fertilidad femenina en los últimos años, así como la amplia presencia en nuestro entorno de contaminantes capaces de alterar el adecuado funcionamiento del sistema endocrino, hace que el papel del medio ambiente esté cobrando cada vez más importancia (13). Surge así la necesidad de clarificar la posible relación existente entre los disruptores endocrinos y las posibles alteraciones a nivel reproductivo que se pudieran desprender de dicha exposición (3), por lo que el objetivo de esta revisión narrativa es estudiar la relación entre la exposición a bisfenol A y el SOP debido a su creciente interés.

¿Qué sabemos del bisfenol A?

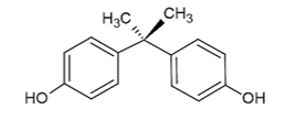

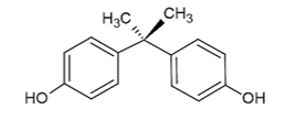

El bisfenol A (Fig. 1) es un compuesto industrial con capacidad de mimetizar el efecto de las hormonas estrogénicas. Se trata de un disruptor endocrino ampliamente utilizado en la manufacturación de numerosos productos de consumo (14). Los disruptores endocrinos son agentes que interfieren en la síntesis, secreción, transporte, unión, acción o eliminación de las hormonas naturales del organismo responsables del mantenimiento de la homeostasis, la reproducción, el desarrollo y/o el comportamiento (15). Además, debido a los efectos observados del bisfenol A en el cambio de varias rutas metabólicas en humanos, particularmente en aquellas relacionadas con la regulación hormonal de los procesos reproductivos, el bisfenol A se considera un xenoestrógeno. Los xenoestrógenos incluyen compuestos que alteran la síntesis, el transporte, la actividad y el metabolismo de los estrógenos endógenos. Así, afectan el crecimiento, el desarrollo y la reproducción de los organismos (4, 16).

Figura 1. Estructura química del Bisfenol A.

El bisfenol A fue sintetizado por primera vez por Alexander Pavlovich Dianin en 1891 y fue reconocido en 1930 por el químico británico Charles Edward Dodds como un estrógeno artificial. Poco después, se probó en la prevención de los resultados adversos del embarazo en mujeres con antecedentes de aborto espontáneo hasta que, en 1947, la FDA aprobó el dietilestilbestrol (2). Posteriormente, en la década de los 50, comenzó a usarse en la industria. En 2008 su producción se estimó en unos 5,2 millones de toneladas en todo el mundo y alcanzó 7,7 millones de toneladas en 2015. Su producción ha llegado a alcanzar los 7,7 millones de toneladas en 2015 y se estima que su consumo se vea incrementado hasta 10,6 millones de toneladas en 2022 (6).

Aunque la seguridad del bisfenol A en productos de consumo está ampliamente garantizada, diversos estudios realizados durante los últimos veinte años indican que este compuesto no solo está ampliamente distribuido en el medioambiente, sino que también presenta toxicidad incluso a bajas dosis (4). Esto es debido a que las reacciones adversas en la salud humana generalmente son resultado de una exposición crónica (5).

Normalmente, este contaminante se encuentra en muestras de orina y sangre, confirmando la alta exposición a estos químicos (3). La ingestión oral es la principal fuente de exposición en humanos, aunque existen numerosas vías de exposición (Fig. 2.). Se han encontrado evidencias de que el bisfenol A puede penetrar en los alimentos por contacto prolongado con envases de plástico, papel o incluso en latas, durante el tiempo de almacenamiento. Además, procesos como el lavado y el calentamiento, pueden estimular la liberación del bisfenol A y, en consecuencia, incrementar su concentración en alimentos. De igual manera, se ha demostrado que el bisfenol A puede liberarse de la estructura de los biberones (4).

Figura 2. Fuentes de exposición a bisfenol A.

Estas circunstancias han favorecido la instauración de numerosas políticas restrictivas, como la Directiva 2011/8/UE que prohíbe el uso del bisfenol A en biberones debido al desconocimiento sobre los efectos adversos de este compuesto en los cambios bioquímicos producidos en el cerebro, su actividad inmunomoduladora y el riesgo de desarrollar cáncer de mama (4). Además, la ingesta diaria recomendada en Europa ha disminuido de 50 mg/kg por peso/día a 4 mg/kg por peso/día (6).

Ya que el bisfenol A puede interactuar con los receptores estrogénicos, es obvio que puede interferir en la fertilidad femenina (2) alterando la esteroidogénesis, la foliculogénesis y la morfología ovárica (3). Además, la exposición a bisfenol A podría estar relacionada con alteraciones en la producción de ovocitos, así como una afectación negativa de la fertilidad humana por la interrupción de la síntesis de la actividad de los esteroides sexuales (4). Asimismo, el bisfenol A está asociado a enfermedades metabólicas como la diabetes tipo 2, una sensibilidad reducida a la insulina, alteraciones en el metabolismo de la glucosa y los lípidos, mayor riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular, etc. (5).

¿Qué sabemos del SOP?

El SOP no fue descrito hasta principios del siglo XX por Lesnoy en 1928 y por Stein y Leventhal en 1935 (17). A partir de este momento, los criterios diagnósticos se han modificado a lo largo del tiempo, cobrando importancia este síndrome a partir de la conferencia internacional sobre SOP promovida por el National Institutes of Health (NIH) en 1990. Fue en 2003 cuando se consiguió una estandarización de los mismos con los Criterios de Rotterdam para el diagnóstico del SOP (18). Otro aporte importante en la definición del síndrome son los criterios de 2006 de la Androgen Excess Society (AES) (19). Finalmente, en el Evidence-Based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome de 2012 se intentó zanjar y unificar las consideraciones sobre la enfermedad, pero los resultados no fueron publicados de forma que tuviesen un gran impacto ni autoridad. Actualmente los criterios más aceptados son los criterios de Rotterdam mencionados previamente (20, 21).

El SOP se caracteriza por una serie de signos y síntomas (Fig. 3). Los más frecuentes están asociados a la producción excesiva de andrógenos, incluyendo hirsutismo, alopecia y acné. El crecimiento del vello es especialmente típico en barbilla, cuello, parte baja de la cara y zona preauricular. Además, se suele dar un crecimiento de vello excesivo en la parte baja de la espalda, abdomen, nalgas, área perineal, interior de los muslos y área periareolar. Por otra parte, la disfunción ovulatoria, las irregularidades menstruales y los problemas de fertilidad son también comunes en las mujeres con SOP (22). Aunque no son estrictamente necesarios para un diagnóstico, la resistencia a la insulina y la morfología de ovario poliquístico pueden también formar parte de la manifestación del SOP. El aumento de peso y la resistencia a la insulina son muy comunes, variando la prevalencia de esta última entre 40 % y 70 % al utilizar marcadores alternativos (23). Por su parte, la evaluación de la morfología del ovario se realiza por ultrasonografía, considerando que hay morfología de ovario poliquístico cuando el volumen de un ovario es ≥10ml y/o hay un número aumentado de folículos antrales (7).

Figura 3. Signos y síntomas del SOP.

Como posible solución a las dificultades que surgen al intentar estandarizar los criterios diagnósticos, nace un acuerdo promovido por la European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) y la American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Según dicho acuerdo, el SOP puede ser diagnosticado si dos de los siguientes tres criterios se cumplen: i) hiperandrogenismo clínico o bioquímico, ii) oligomenorrea crónica y/o anovulación, iii) presencia de ovarios poliquísticos en ultrasonografía transvaginal. Estos son conocidos como los Criterios de Rotterdam para el diagnóstico del SOP. Los cuatro fenotipos actuales del SOP se definen según las diferentes combinaciones de sus características. El fenotipo 1, también llamado fenotipo “completo” del SOP, incluye hiperandrogenismo, disfunción ovárica y morfología de ovario poliquístico. En el resto de fenotipos solo se presentan dos de los tres criterios: fenotipo 2 (hiperandrogenismo y disfunción ovárica), fenotipo 3 (hiperandrogenismo y morfología de ovario poliquístico), y fenotipo 4 (disfunción ovárica y morfología de ovario poliquístico) (7).

Además de las características propias del síndrome, el SOP se encuentra relacionado con una fertilidad disminuida y complicaciones en el embarazo, obesidad y dislipemia, resistencia a la insulina y diabetes tipo 2, síndrome metabólico, mayor riesgo de ansiedad y depresión, mayor riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular (10) y mayor riesgo de hiperplasia endometrial y carcinoma (7).

A pesar de que la fisiopatología del SOP no está clara, una evidencia creciente apunta a que se trata de un trastorno multigenético complejo con fuertes influencias epigenéticas y medioambientales (21). Pacientes con SOP muestran alteraciones en el eje hipotálamo-pituitaria y en la sensibilidad de los folículos a hormonas, resistencia a la insulina y disfuncionalidad de los adipocitos (7). Se puede entender el SOP como un estado de inflamación crónica a un nivel bajo y como tal es necesaria la adopción de un estilo de vida que no incentive el estrés oxidativo, la acidosis ni la activación inmune con el objetivo de paliarlo (24).

Relación entre Bisfenol A y el SOP. ¿Qué dice la evidencia?

Múltiples trabajos de investigación han tratado de describir la relación existente entre el bisfenol A y el SOP con la intención de dilucidar el papel que juega dicho compuesto en su etiología debido a su capacidad para interaccionar con el sistema endocrino. Entre los tipos de estudio que han abordado esta temática se encuentran experimentos in vivo e in vitro (4, 25) o, incluso, estudios epidemiológicos de tipo transversal y longitudinal (3, 26, 27).

En cuanto a los resultados reportados por los estudios epidemiológicos, se ha podido observar de forma generalizada la presencia de bisfenol A en el organismo, siendo mayor en mujeres diagnosticadas de SOP (3, 26, 27). Basándose en esta evidencia, se podría afirmar que la exposición previa a contaminantes ambientales que actúan como disruptores endocrinos es un factor de riesgo para desarrollar dicho síndrome (27). De esta forma, en el estudio transversal realizado por Zhou et al. se llegó a detectar una concentración media en orina de 2,35 ng/ml en mujeres con SOP, un nivel superior al registrado en otras mujeres sin dicha patología (1). En esta misma línea, otros autores señalan cómo en comparación con los sujetos que conformaban el grupo de controles sanos, la presencia de bisfenol sérico es significativamente más elevada en mujeres con esta patología (28).

Estos estudios no solo han documentado la amplia presencia de bisfenol A en el organismo, sino que también se ha podido observar una disminución significativa en el recuento de folículos antrales, así como unos niveles inferiores de la hormona antimulleriana y folículo estimulante. Esto se asoció con una disminución relativa de la reserva ovárica en las mujeres que conformaban la muestra (1). Además, otra consecuencia es el hiperandrogenismo, correlacionado positivamente con los niveles de testosterona total en suero y el índice de andrógenos libres (28, 29). Este hecho podría estar relacionado con la estimulación de la estructura celular que envuelve al antro folicular. Se produce una desregulación de la enzima 17-α-hidroxilasa que es clave en la esteroidogénesis gonadal (29). Sin embargo, otros estudios sugieren que estas alteraciones características del SOP, pueden ser también resultado de la exposición a otros contaminantes ambientales como por ejemplo a difenil-éteres bromados, plaguicidas organoclorados, compuestos perfluorados o ftalatos (27).

Respecto al resto de criterios diagnósticos del SOP, en otros estudios transversales se ha podido observar cómo en mujeres que tenían unos niveles de bisfenol A elevados en orina, existía una relación cintura-altura significativamente más alta. Se justifica así una posible tendencia al sobrepeso, niveles de insulina superiores al límite de referencia (24,9 mUI/L) y una mayor resistencia a la insulina evidenciada por el modelo homeostático (HOMA-IR) (5, 29). En esta misma población aparece una alteración del perfil lipídico con unos niveles de colesterol total y triglicéridos moderadamente elevados, así como una disminución del HDL respecto a los controles. Así mismo, se observó un aumento en los niveles de leptina, hormona responsable de regular el apetito, que quizás pueda explicar el aumento de peso en mujeres diagnosticadas de SOP (5).

En otros ensayos controlados en laboratorio, como son los experimentos in vivo e in vitro (4, 25), también se han apreciado alteraciones reproductivas relacionadas con el SOP. Se han observado ciclos irregulares, así como una alteración en el desarrollo ovárico con una disminución de cuerpos lúteos y folículos antrales, además de un aumento de los folículos atrésicos y la presencia de quistes que dan nombre a esta patología (4, 25).

Conclusión

El bisfenol A es un contaminante en auge en la industria y que parece tener una relación directa con la salud reproductiva. A la misma vez, el SOP es una enfermedad cada vez más prevalente. En líneas generales, la literatura que ha sido incluida en esta revisión apunta a que el bisfenol A podría exacerbar el riesgo metabólico en las mujeres con SOP o incluso formar parte de su etiología, debido a su capacidad para interferir en el sistema endocrino y hormonal. Además, potenciaría la ganancia de peso, la hiperinsulinemia y la resistencia a la insulina, así como la dislipemia y el hiperandrogenismo. Debido a la escasez de estudios existentes, se hace imprescindible seguir analizando el efecto que este compuesto pudiera tener sobre la salud reproductiva, en particular en el SOP. Este hecho repercutiría en posibles restricciones futuras en su uso industrial reduciendo así su presencia a nivel ambiental. En esta línea, sería adecuada la realización de más estudios de carácter epidemiológico que avalen el impacto de la exposición prolongada a bisfenol A y permitan establecer una asociación causal más sólida.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Zhou W, Fang F, Zhu W, Chen ZJ, Du Y, Zhang J. Bisphenol A and Ovarian Reserve among Infertile Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;14(1):1-7.

- Rutkowska A, Rachon D. Bisphenol A (BPA) and its potential role in the pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(4):260-5.

- Akgul S, Sur U, Duzceker Y, Balci A, Kizilkan MP, Kanbur N, et al. Bisphenol A and phthalate levels in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(12):1084-7.

- Tomza-Marciniak A, Stepkowska P, Kuba J, Pilarczyk B. Effect of bisphenol A on reproductive processes: A review of in vitro, in vivo and epidemiological studies. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38(1):51-80.

- Milanovic M, Milosevic N, Sudji J, Stojanoski S, Atanackovic Krstonosic M, Bjelica A, et al. Can environmental pollutant bisphenol A increase metabolic risk in polycystic ovary syndrome? Clin Chim Acta. 2020;507:257-63.

- Jurewicz J, Majewska J, Berg A, Owczarek K, Zajdel R, Kaleta D, et al. Serum bisphenol A analogues in women diagnosed with the polycystic ovary syndrome – is there an association? Environ Pollut. 2021;272(115962):1-7.

- Azziz R. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(2):321-36.

- Eftekhar T, Sohrabvand F, Zabandan N, Shariat M, Haghollahi F, Ghahghaei-Nezamabadi A. Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and its affected domains. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12(8):539-46.

- Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, Dokras A. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(5):1075-91.

- Louwers YV, Laven JSE. Characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome throughout life. Ther Adv Reprod Health. 2020;14:1-9.

- Joham AE, Teede HJ, Ranasinha S, Zoungas S, Boyle J. Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(4):299-307.

- Caldwell ASL, Edwards MC, Desai R, Jimenez M, Gilchrist RB, Handelsman DJ, et al. Neuroendocrine androgen action is a key extraovarian mediator in the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(16):E3334-E43.

- Huo X, Chen D, He Y, Zhu W, Zhou W, Zhang J. Bisphenol-A and Female Infertility: A Possible Role of Gene-Environment Interactions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):11101-16.

- Wang Y, Zhu Q, Dang X, He Y, Li X, Sun Y. Local effect of bisphenol A on the estradiol synthesis of ovarian granulosa cells from PCOS. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(1):21-5.

- Fernandez M, Bourguignon N, Lux-Lantos V, Libertun C. Neonatal exposure to bisphenol a and reproductive and endocrine alterations resembling the polycystic ovarian syndrome in adult rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(9):1217-22.

- Rashidi B, Amanlou M, Lak T, Ghazizadeh M, Haghollahi F, Bagheri M, et al. The Association Between Bisphenol A and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Acta Med Iran. 2017;55(12):759-64.

- Rodgers RJ, Suturina L, Lizneva D, Davies MJ, Hummitzsch K, Irving-Rodgers HF, et al. Is polycystic ovary syndrome a 20th Century phenomenon? Med Hypotheses. 2019;124:31-4.

- Rotterdam EA-SPCWG. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. FertilSteril. 2004;81(1):19-25.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4237-45.

- NIH. Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) 2012 [consultado 22/03/2021. Disponible en: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/newsroom/resources/spotlight/112112-pcos.

- Escobar-Morreale HF. Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(5):270-84.

- Meier RK. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53(3):407-20.

- Macut D, Bjekic-Macut J, Rahelic D, Doknic M. Insulin and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:163-70.

- Patel S. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;182:27-36.

- Yang Z, Shi J, Guo Z, Chen M, Wang C, He C, et al. A pilot study on polycystic ovarian syndrome caused by neonatal exposure to tributyltin and bisphenol A in rats. Chemosphere. 2019;231:151-60.

- Kandaraki E, Chatzigeorgiou A, Livadas S, Palioura E, Economou F, Koutsilieris M, et al. Endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): elevated serum levels of bisphenol A in women with PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E480-E4.

- Vagi SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Sjodin A, Calafat AM, Dumesic D, Gonzalez L, et al. Exploring the potential association between brominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, perfluorinated compounds, phthalates, and bisphenol A in polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14(86):1-12.

- Konieczna A, Rachon D, Owczarek K, Kubica P, Kowalewska A, Kudlak B, et al. Serum bisphenol A concentrations correlate with serum testosterone levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Toxicol. 2018;82:32-7.

- Akin L, Kendirci M, Narin F, Kurtoglu S, Saraymen R, Kondolot M, et al. The endocrine disruptor bisphenol A may play a role in the aetiopathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescent girls. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(4):e171-e7.

Bisphenol A Exposure and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Increasing Problem

Bisphenol A belongs to a group of environmental pollutants, called endocrine disruptors, whose relationship with various health disorders is becoming increasingly evident. One of these disorders is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). This narrative review attempts to define key aspects of both bisphenol A and PCOS, as well as to consolidate the current knowledge about them with the aim to establish a solid basis for their relationship and implication in health. Different studies point out a possible relationship not only between PCOS and exposure to bisphenol A, but also to other diseases that are more prevalent in women with this syndrome, such as disorders in hormone regulation or metabolism. It is necessary, however, to deepen the knowledge about the relationship between bisphenol A and PCOS in order to provide more evidence. To this effect, it would be interesting to develop different epidemiological studies focused on strengthening and reaffirming the potential causal association.

Keywords: bisphenol A, polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS, endocrine disruptor, reproductive health.

Introduction

Endocrine disruptors belong to a heterogeneous group of molecules (natural or synthetic) which can interfere with the endocrine system. This is because their phenolic structure can mimic or antagonize endogenous steroid hormones (1) and cause different metabolic disorders, even the development of hormone-dependent cancers (2).

Bisphenol A is one of the endocrine disruptors most frequently found in the environment (3). This is mainly due to its increasing industrial use in the production of many synthetic materials or polycarbonates, among others (4). It is considered a ubiquitous compound that can be found in reusable bottles, plastic and metal items used in food packaging, toys, medical equipment or even dental compounds. In this regard, several studies reported that it is present in the air, dust or water, with ingestion of contaminated food and water being the main route of exposure (5). However, absorption through the skin and respiratory system can also occur (6). In this line, studies developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed a detectable level of bisphenol A in samples of urine, amniotic fluid, placental tissue, umbilical cord and fetal serum (4). This compound has been detected in follicular fluid, suggesting that oocytes would have been exposed to this contaminant agent during the folliculogenesis (1).

On the other hand, PCOS is characterized by a heterogeneous presence of anovulation, hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian morphology, metabolic dysfunction and infertility (7). In addition, this syndrome is associated with sexual and psychological problems (8). Thus, it increases the probability of having symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (9).

Globally, it is considered the most common and heterogeneous endocrine disorder in women of child-bearing age (10). Its prevalence is between 6% and 21% depending on the diagnostic criteria (11). In addition, more than 75% of cases of anovulatory infertility are ascribed to PCOS (12).

Although the pathophysiology of the syndrome is not clear, an increased prevalence of reproductive diseases, a decreased female fertility in recent years, and a strong presence in our environment of pollutants capable of altering the proper function of the endocrine system, make the role of the environment increasingly important (13). Hence, a need arises for clarifying the potential relationship between endocrine disruptors and the potential reproductive disorders that could result from such exposure (3). Therefore, the objective of this narrative review is to study the relationship between bisphenol A exposure and PCOS because of the growing interest in this topic.

What do we know about bisphenol A?

Bisphenol A (Figure 1) is an industrial compound able to mimic the effect of estrogenic hormones. It is an endocrine disruptor widely used in the manufacture of many consumer goods (14). Endocrine disruptors are agents that interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, binding, action or elimination of the body’s natural hormones responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis, reproduction, development and/or behavior (15). Additionally, due to the effects shown by bisphenol A in changing several metabolic pathways in humans, particularly those related to hormonal regulation of reproductive processes, bisphenol A is considered a xenoestrogen. Xenoestrogens include compounds that modify the synthesis, transport, activity and metabolism of endogenous estrogens. Therefore, they affect the growth, development and reproduction of organisms (4, 16).

Figure 1. Molecular structure of bisphenol A

Bisphenol A was first synthesized by Alexander Pavlovich Dianin in 1891. It was recognized as an artificial estrogen by the British chemist Charles Edward Dodds in 1930. Shortly thereafter, it was tested for the prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with a history of miscarriage. It was not until 1947 when the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved diethylstilbestrol (2). Subsequently, the industrial use of Bisphenol A began in the 1950s. In 2008 its production was estimated at about 5.2 million tons worldwide and reached 7.7 million tons in 2015. The consumption is estimated to increase to 10.6 million tons in 2022 (6).

Although the safety of bisphenol A in consumer goods is largely guaranteed, several studies conducted over the last twenty years claim that this compound is not only widely distributed in the environment, but also exhibits toxicity even at low doses (4). This is because adverse reactions in humans generally result from chronic exposure (5).

This pollutant is commonly found in urine and blood samples, confirming the high exposure to these chemicals (3). Oral ingestion is the main source of exposure in humans, although there are many routes of exposure (Figure 2). Evidence has been found that bisphenol A can enter food during the storage time by prolonged contact with plastic, paper containers or even cans. In addition, processes such as washing and heating can stimulate its release, increasing its concentration in food. It has also been shown that bisphenol A can be released from feeding bottle materials (4).

Figure 2. Sources of bisphenol A exposure

These circumstances have encouraged the implementation of numerous restrictive policies, such as Directive 2011/8/EU. This directive prohibits the use of bisphenol A in feeding bottles due to the lack of knowledge about its adverse effects on the biochemical changes in the brain, the immunomodulatory activity, and the risk of developing breast cancer (4). In addition, the recommended daily intake in Europe has decreased from 50 mg/kg bw/day to 4 mg/kg bw/day (6).

Since bisphenol A can interact with estrogen receptors, it can interfere with fertility in women (2) by modifying steroidogenesis, folliculogenesis and ovarian morphology (3). Furthermore, its exposure could be related to alterations in oocyte production and adverse effects on human fertility by disrupting the synthesis of sex steroid activity (4). Bisphenol A is also associated with metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, reduced insulin sensitivity, alterations in glucose and lipid metabolism, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, among others (5).

What do we know about PCOS?

PCOS was first described at the beginning of the 20th century by Lesnoy in 1928 and by Stein and Leventhal in 1935 (17). The diagnostic criteria have been modified over time. Moreover, this syndrome has become important after the international conference on PCOS promoted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1990. It was in 2003 when these criteria were standardized to the Rotterdam criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS (18).

Another important contribution to the syndrome’s definition are the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society’s (AE-PCOS) criteria from 2006 (19). There was an attempt to settle and unify the observations relevant to the disease on the Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome from 2012. However, the results did not have a great impact. Nowadays, Rotterdam criteria are the most widely accepted (20, 21).

PCOS is characterized by a number of signs and symptoms (Figure 3). The most frequent are related to excessive androgen production, including hirsutism, alopecia and acne. Hair growth is particularly typical on the chin, neck, lower face and preauricular area. Excessive hair growth usually occurs on the lower back, abdomen, buttocks, perineal area, inner thighs, and periareolar area. Ovulatory dysfunction, irregular periods and fertility problems are common in women with PCOS (22). Insulin resistance and polycystic ovarian morphology can also be part of the manifestation of PCOS, although they are not strictly necessary for a diagnosis. Weight gain and insulin resistance are very common, varying the prevalence of insulin resistance between 40% and 70% when using alternative markers (23). The examination of ovarian morphology is performed by ultrasonography, which will confirm polycystic ovarian morphology when the volume of an ovary is ≥ 10 ml and/or there is an increase in antral follicles (7).

Figure 3. PCOS signs and symptoms

An agreement between the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) was promoted as a possible solution to the difficulties for the standardization of diagnostic criteria. According to the agreement, PCOS can be diagnosed when two of the three following criteria are met: i) clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism; ii) chronic oligomenorrhea and/or anovulation; iii) presence of polycystic ovaries in transvaginal ultrasound scan. These are known as the Rotterdam criteria for PCOS diagnosis. There are currently four recognized PCOS phenotypes, which are defined by different combinations of the syndrome’s features. Phenotype 1, also called “complete” PCOS phenotype, includes hyperandrogenism, primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), and polycystic ovarian morphology. In the rest of the phenotypes, however, only two of the three criteria are present: phenotype 2 includes hyperandrogenism and POI; phenotype 3, hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovarian morphology; and phenotype 4, POI and polycystic ovarian morphology (7).

In addition to its own characteristics, PCOS is related to decreased fertility and complications during pregnancy, obesity and dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, higher risk of anxiety and depression, higher risk of cardiovascular disease (10), and higher risk of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma (7).

Despite its unclear pathophysiology, growing evidence suggests that PCOS might be a complex multigenetic disorder with strong epigenetic and environmental influences (21). Patients with PCOS showed alterations in their hypothalamic–pituitary axis and follicle sensitivity to hormones, insulin resistance and adipocyte dysfunction (7). PCOS can be understood as a state of chronic inflammation at a low level, which makes it necessary to adopt a lifestyle avoiding oxidative stress, acidosis or immune activation in order to alleviate it (24).

Bisphenol A and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. What is the evidence?

Since bisphenol A can interact with the endocrine system, many research studies have tried to describe its relationship with PCOS. The aim was to discern the role that bisphenol A plays in PCOS etiology. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments (4, 25), as well as transversal and longitudinal epidemiological studies, have been conducted to study this topic (3, 26, 27).

As for the results provided by the epidemiological studies, the wide presence of bisphenol A in the organism has been observed, being higher in women diagnosed with PCOS (3, 26, 27). Based on this evidence, the previous exposure to environmental pollutants that act as endocrine disruptors could be a risk factor for developing this syndrome (27). Therefore, in the cross-sectional study conducted by Zhou et al., a mean concentration of 2.35 ng/ml was detected in the urine of women with PCOS, being a higher level than the one recorded in other women without this pathology (1). Accordingly, other authors pointed out how, when compared to the healthy controls, the presence of serum bisphenol A is significantly larger in women with PCOS (28).

These studies have not only documented the widespread presence of bisphenol A in the organism, but also a significant decrease in the antral follicle count, along with lower levels of the anti-Müllerian hormone and the follicle stimulating hormone. This was associated with a relative decrease in the ovarian reserve of the women in the sample (1). Another consequence is hyperandrogenism, positively correlated with serum total testosterone levels and the free androgen index (28, 29). This could be related to the stimulation of the cell structure surrounding the follicular antrum. The 17-α-hydroxylase enzyme, key in the gonadal steroidogenesis, is deregulated (29). However, other studies suggest that these alterations, characteristic of PCOS, can also be the result of the exposure to other environmental pollutants such as brominated diphenyl ethers, organochlorine pesticides, perfluorinated compounds or phthalates (27).

Regarding the rest of the criteria for PCOS diagnosis, other cross-sectional studies have shown a significantly larger waist-to-height ratio in women with higher bisphenol A levels in their urine. This justifies a possible tendency to be overweight, insulin level above the reference limit (24.9 mIU/L) and a greater resistance to insulin evidenced by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR) (5, 29). This same population shows an alteration of the lipid profile with moderately elevated total cholesterol and triglycerides levels, along with a decrease of the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) compared to controls. Moreover, an increase in the leptin levels was observed. This increment of the hormone responsible for regulating the appetite may explain weight gain in women diagnosed with PCOS (5).

In other controlled trials in laboratory, such as in vivo and in vitro experiments (4, 25), reproductive alterations related to PCOS have also been observed. Irregular periods, alterations in the ovarian development with a decrease in corpus luteum and antral follicles, in addition to an increase in atretic follicles and the presence of cysts that give name to this pathology, have been observed (4, 25).

Conclusion

Bisphenol A is a pollutant that is on the rise in the industry and seems to have a direct correlation to reproductive health. At the same time, PCOS has become an increasingly prevalent disease. In general, the literature included in this revision suggests that bisphenol A may exacerbate the metabolic risk in women with PCOS or even be part of their etiology due to its ability to interfere with the endocrine system. Furthermore, bisphenol A would enhance weight gain, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, along with dyslipidemia and hyperandrogenism. Due to the lack of studies, it is essential to further analyze the impact that this compound could have on reproductive health, particularly on PCOS. This could result in the implementation of future restrictions on its industrial use, thus reducing its presence on an environmental level. Consequently, it would be appropriate to carry out further epidemiological studies to assess the impact to a long-term bisphenol A exposure, enabling the establishment of a more solid causal association.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou W, Fang F, Zhu W, Chen ZJ, Du Y, Zhang J. Bisphenol A and Ovarian Reserve among Infertile Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;14(1):1-7.

- Rutkowska A, Rachon D. Bisphenol A (BPA) and its potential role in the pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(4):260-5.

- Akgul S, Sur U, Duzceker Y, Balci A, Kizilkan MP, Kanbur N, et al. Bisphenol A and phthalate levels in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(12):1084-7.

- Tomza-Marciniak A, Stepkowska P, Kuba J, Pilarczyk B. Effect of bisphenol A on reproductive processes: A review of in vitro, in vivo and epidemiological studies. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38(1):51-80.

- Milanovic M, Milosevic N, Sudji J, Stojanoski S, Atanackovic Krstonosic M, Bjelica A, et al. Can environmental pollutant bisphenol A increase metabolic risk in polycystic ovary syndrome? Clin Chim Acta. 2020;507:257-63.

- Jurewicz J, Majewska J, Berg A, Owczarek K, Zajdel R, Kaleta D, et al. Serum bisphenol A analogues in women diagnosed with the polycystic ovary syndrome – is there an association? Environ Pollut. 2021;272(115962):1-7.

- Azziz R. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(2):321-36.

- Eftekhar T, Sohrabvand F, Zabandan N, Shariat M, Haghollahi F, Ghahghaei-Nezamabadi A. Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and its affected domains. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12(8):539-46.

- Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, Dokras A. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(5):1075-91.

- Louwers YV, Laven JSE. Characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome throughout life. Ther Adv Reprod Health. 2020;14:1-9.

- Joham AE, Teede HJ, Ranasinha S, Zoungas S, Boyle J. Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(4):299-307.

- Caldwell ASL, Edwards MC, Desai R, Jimenez M, Gilchrist RB, Handelsman DJ, et al. Neuroendocrine androgen action is a key extraovarian mediator in the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(16):E3334-E43.

- Huo X, Chen D, He Y, Zhu W, Zhou W, Zhang J. Bisphenol-A and Female Infertility: A Possible Role of Gene-Environment Interactions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):11101-16.

- Wang Y, Zhu Q, Dang X, He Y, Li X, Sun Y. Local effect of bisphenol A on the estradiol synthesis of ovarian granulosa cells from PCOS. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(1):21-5.

- Fernandez M, Bourguignon N, Lux-Lantos V, Libertun C. Neonatal exposure to bisphenol a and reproductive and endocrine alterations resembling the polycystic ovarian syndrome in adult rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(9):1217-22.

- Rashidi B, Amanlou M, Lak T, Ghazizadeh M, Haghollahi F, Bagheri M, et al. The Association Between Bisphenol A and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Acta Med Iran. 2017;55(12):759-64.

- Rodgers RJ, Suturina L, Lizneva D, Davies MJ, Hummitzsch K, Irving-Rodgers HF, et al. Is polycystic ovary syndrome a 20th Century phenomenon? Med Hypotheses. 2019;124:31-4.

- Rotterdam EA-SPCWG. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. FertilSteril. 2004;81(1):19-25.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4237-45.

- NIH. Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) 2012 [Last access: 21/11/2012]. Available at: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/newsroom/resources/spotlight/112112-pcos.

- Escobar-Morreale HF. Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(5):270-84.

- Meier RK. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53(3):407-20.

- Macut D, Bjekic-Macut J, Rahelic D, Doknic M. Insulin and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:163-70.

- Patel S. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;182:27-36.

- Yang Z, Shi J, Guo Z, Chen M, Wang C, He C, et al. A pilot study on polycystic ovarian syndrome caused by neonatal exposure to tributyltin and bisphenol A in rats. Chemosphere. 2019;231:151-60.

- Kandaraki E, Chatzigeorgiou A, Livadas S, Palioura E, Economou F, Koutsilieris M, et al. Endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): elevated serum levels of bisphenol A in women with PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E480-E4.

- Vagi SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Sjodin A, Calafat AM, Dumesic D, Gonzalez L, et al. Exploring the potential association between brominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, perfluorinated compounds, phthalates, and bisphenol A in polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14(86):1-12.

- Konieczna A, Rachon D, Owczarek K, Kubica P, Kowalewska A, Kudlak B, et al. Serum bisphenol A concentrations correlate with serum testosterone levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Toxicol. 2018;82:32-7.

- Akin L, Kendirci M, Narin F, Kurtoglu S, Saraymen R, Kondolot M, et al. The endocrine disruptor bisphenol A may play a role in the aetiopathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescent girls. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(4):e171-e7.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Pérez-Díaz C, Miranda-García M, González-Acedo A. Exposición a bisfenol A y síndrome de ovario poliquístico: un problema emergente. AMU. 2021; 3(1):124-135