Julia Belinda Poncela-Díaz 1,2; Melanie Pacheco-Nunes 3,4; Elena Giménez-Gironda 5,6; Lucia Gállová 7

1 Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud (Enfermería), Universidad de La Laguna (ULL)

2 Máster en Cuidados Críticos en Urgencias y Emergencias en Enfermería, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

3 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras (Filosofía), Universidad de Granada (UGR)

4 Máster en Bioética, Universidad Internacional de Valencia (VIU)

5 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Valencia (UV)

6 Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio (Granada)

7 Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud (Fisioterapia), Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Sabrina Cherif-Aneche 8; Pablo Tocino-López 8; María Campos-García 8; Mercedes Barrera-Bautista 8; Leila Barakat-Ignacio 8

8 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

Introducción

La contención mecánica (CM) es una práctica con prevalencia significativa, aunque actualmente existe controversia por sus efectos negativos y los dilemas bioéticos que suscita. El objetivo de esta revisión fue determinar la prevalencia y los efectos de la CM en pacientes, los dilemas éticos que provoca en personal sociosanitario, junto con la prevención y técnicas alternativas derivadas del intento de reducir la CM.

Metodología

La búsqueda sistemática se realizó en tres bases de datos: PubMed, Web of Science y Scopus, desde 2012 hasta la actualidad. Se seleccionaron los estudios relacionados con el ámbito sanitario y con los efectos, prevención y alternativas a la contención mecánica. Se excluyeron las revisiones sistemáticas, los estudios cualitativos, aquellos realizados en animales, los no disponibles en inglés o en español, los no finalizados y aquellos sin texto completo disponible.

Resultados

De los 115 artículos encontrados, se incluyeron 20 estudios que cumplieron los criterios de elegibilidad establecidos. Los efectos negativos varían desde la pérdida de autonomía hasta el riesgo de padecer tromboembolismo pulmonar. Los métodos de prevención y reducción de la contención mecánica más utilizados son la formación de los profesionales, el trabajo multidisciplinar y el plan individualizado de tratamiento entre otros. El empleo de nuevas estrategias, basadas en el uso de sistemas electrónicos de identificación temprana de factores de riesgo, podría contribuir en la prevención de la CM, aunque se precisan otros estudios.

Conclusión

Los estudios más antiguos se centran en los efectos de la CM, mientras que los más recientes muestran una clara orientación hacia la reducción y prevención de la misma. La cantidad de nuevos artículos sobre el uso de la CM se ve limitada por el predominio de temas actuales emergentes.

Palabras clave: contención mecánica, efectos, intervenciones, terapias.

Keywords: mechanical restraint, effects, procedures, therapies.

Introducción

La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) define la contención mecánica como “los métodos extraordinarios con finalidad terapéutica que solo resultarán tolerables ante aquellas situaciones de emergencia en las que exista una amenaza urgente o inmediata para la vida y/o integridad física del propio paciente o de terceros y que no puedan conjurarse por otros medios terapéuticos” (1). La contención mecánica (CM) comenzó a utilizarse hace aproximadamente 300 años, principalmente en personas difíciles de controlar (2) con el fin de evitar autolesiones y daños físicos a terceros. Inicialmente, su uso no se consideraba una violación de los derechos humanos por lo que era una práctica aprobada legalmente y de uso extendido en hospitales psiquiátricos. Posteriormente, hubo una progresiva toma de conciencia social y aumento de la visibilidad de la realidad de muchos pacientes, hasta convertirse en un asunto discutido por la disyuntiva legal y ética que plantea (1).

La CM puede ser total si limita la mayoría de movimientos del paciente o parcial si limita solo la movilidad de alguna extremidad o del tronco. Se diferencia de la contención física en que ésta se realiza “cuerpo a cuerpo” sin mediación de otros dispositivos (1,3).

La intención de reducir el uso de la CM se refleja en leyes, principios y reformas relacionados con esta práctica. Uno de los problemas a los que se enfrentan pacientes y profesionales es la falta de un marco legal común al respecto. A nivel europeo nos encontramos referencias a la CM en documentos que legislan sobre derechos humanos como El Convenio para la Protección de los Derechos Humanos y de las Libertades Fundamentales (4). Esto se ejemplifica en casos prácticos, donde el tribunal europeo de derechos humanos condena tratos degradantes contrarios al Convenio, pero no la inmovilización física o mecánica per se (5).

En España, la Ley 41/1986 va dirigida a aquellas acciones que permitan que sea efectivo el derecho a la salud, sin mencionar explícitamente la CM. Sin embargo, la ley 1/1999 del 31 de marzo de Andalucía menciona la CM en relación a usuarios de centros residenciales, haciendo necesario que las medidas privativas de libertad sean aprobadas por la autoridad judicial. Además, la Ley 41/2002 estableció el consentimiento informado como imprescindible excepto en situaciones de preservar la vida y salud del paciente (6).

Las indicaciones actuales para aplicar la CM, según la mayoría de protocolos, son las siguientes:

- Cuando existe un riesgo para la integridad física del paciente, como por ejemplo un riesgo de caídas o autolesiones

- Ante una amenaza física del paciente hacia su entorno u otras personas

- En entornos terapéuticos, como método para evitar arranque de las vías para la medicación o sonda o en situaciones que requieren reposo y no se consigue de otra forma (3).

La CM tiene una prevalencia significativa relacionada en varios estudios con efectos negativos para la salud de los implicados, tanto a nivel físico como mental (7). Además, expone en el personal sanitario diversos conflictos éticos a partir de la confrontación de los derechos del paciente y el deber del equipo sanitario (8-10). Por todo ello, según muestran los últimos estudios, existe un aumento en la identificación de factores predisponentes, el estudio de sus efectos y la utilización de métodos alternativos como la modificación del entorno o tranquilizar de forma verbal (6).

Los protocolos existentes son insuficientes y se deberían ampliar en aras de que las disyuntivas y dilemas éticos de la CM se reduzcan, amparados en un marco legal que responda a estas necesidades (11). Por ello, unido a su relevancia clínica, es importante conocer los factores que suponen mayor o menor riesgo de aplicar CM y los métodos alternativos que pueden usarse. La ambigüedad de las leyes vigentes, la heterogeneidad de los estudios publicados y la disyuntiva bioética actual hacen necesario realizar una gran individualización y enfoque multidisciplinar para abordar este tema.

El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática fue determinar las consecuencias derivadas de la CM, tanto los efectos negativos en la salud física y mental de los pacientes como los dilemas éticos entre los profesionales sanitarios a cargo; delimitar el marco legal de la CM y las situaciones en las que se utiliza actualmente en contextos concretos; y conocer técnicas alternativas en sustitución o prevención de la CM.

Metodología

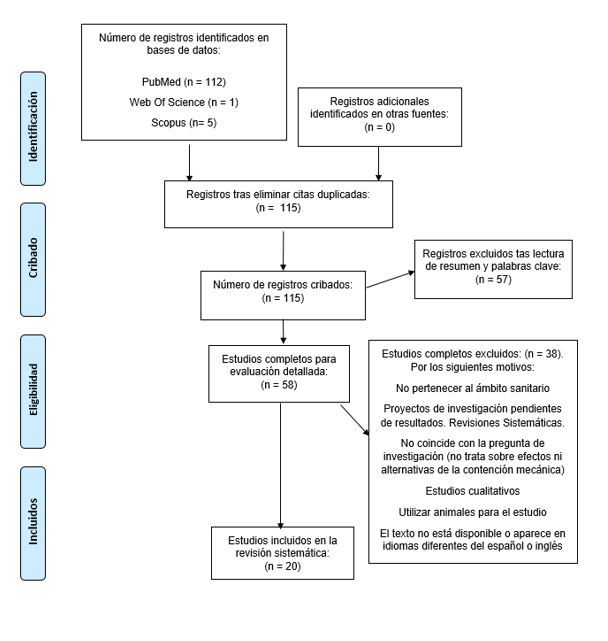

Tras buscar en tres bases de datos entre febrero y marzo de 2021, obtuvimos bibliografía publicada en los últimos diez años empleando la ecuación de búsqueda “Effects AND Physical Restraint AND Europe” (en inglés por ser el idioma de dichas bases de datos). Los resultados fueron analizados entre todas las autoras siguiendo la guía PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) (12). Los criterios de inclusión han sido: aparecer en las bases de datos consideradas, con la ecuación de búsqueda utilizada y tratar sobre la CM. Los criterios de exclusión han sido: no pertenecer al ámbito sociosanitario, no tratar sobre efectos y prevalencia de la CM o de métodos de prevención y alternativas a su uso, utilizar animales en el estudio, ser manuscritos no disponibles o en idiomas distintos de inglés o español, ser estudios cualitativos, ser investigaciones pendientes de resultados y ser revisiones sistemáticas.

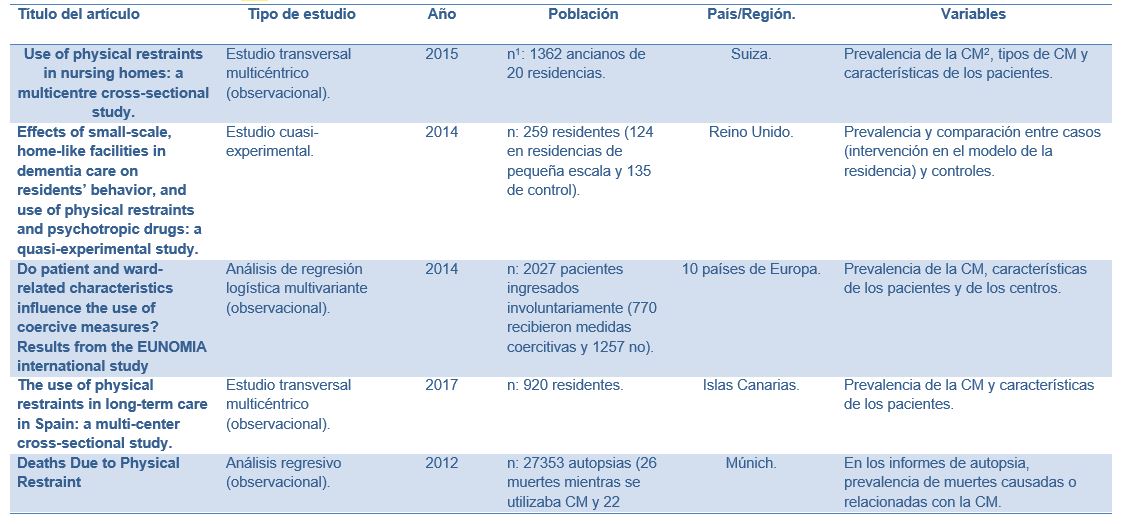

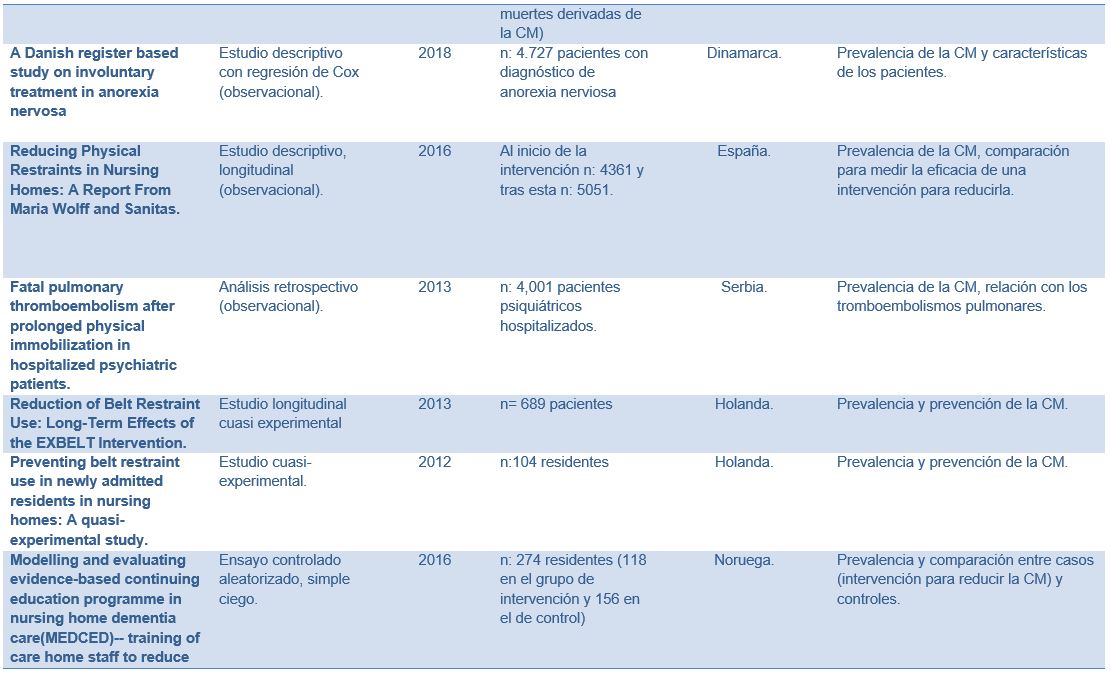

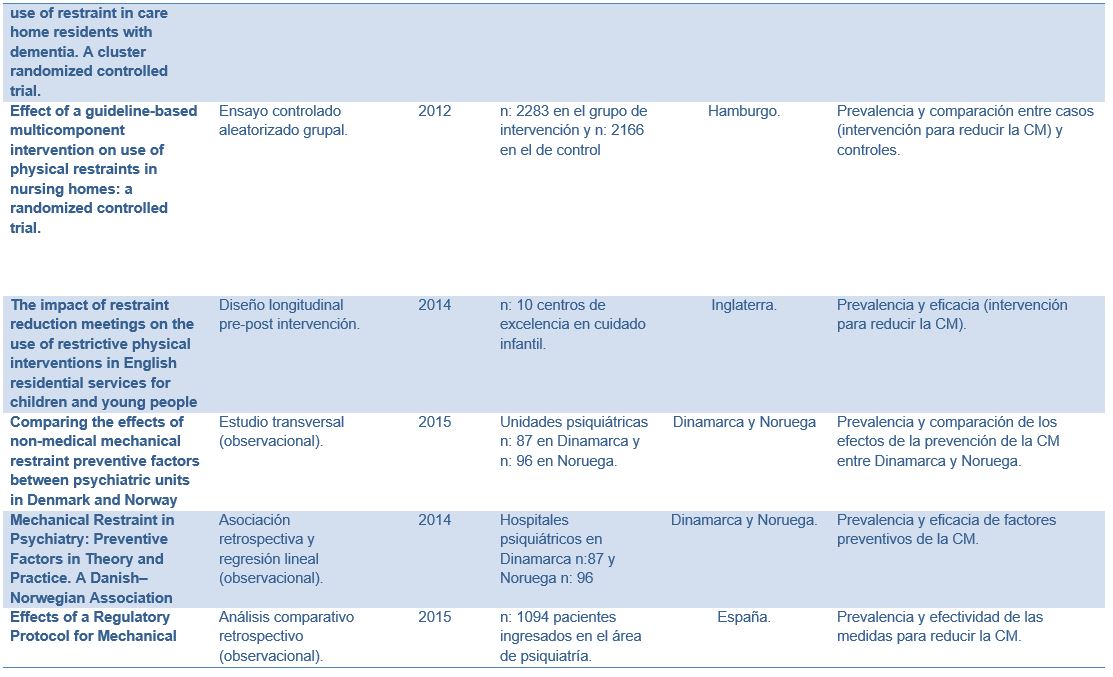

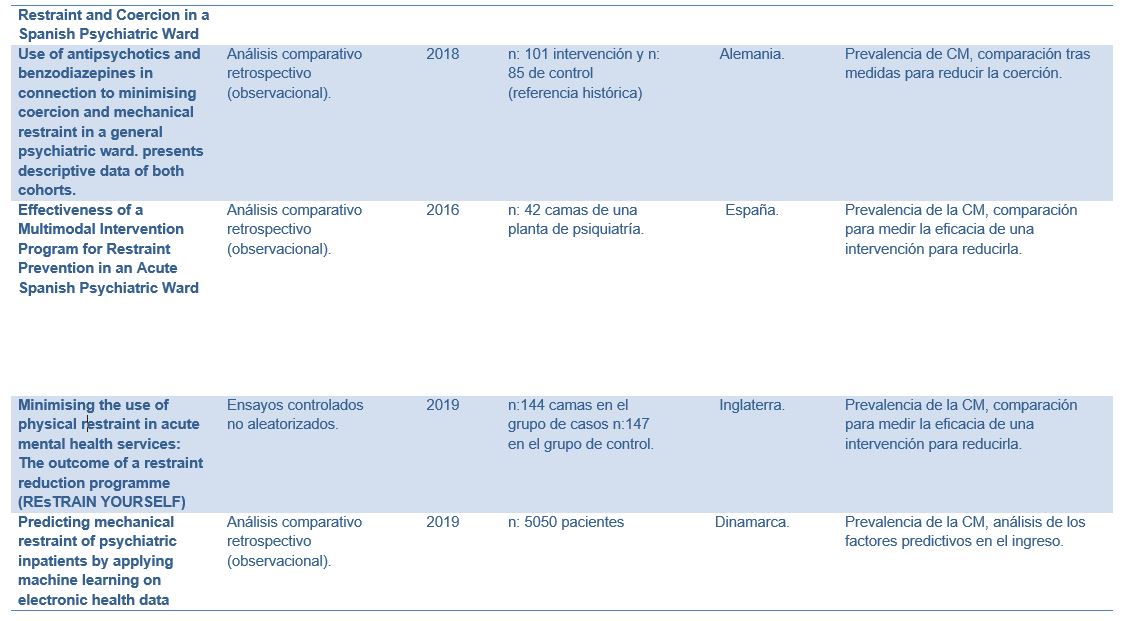

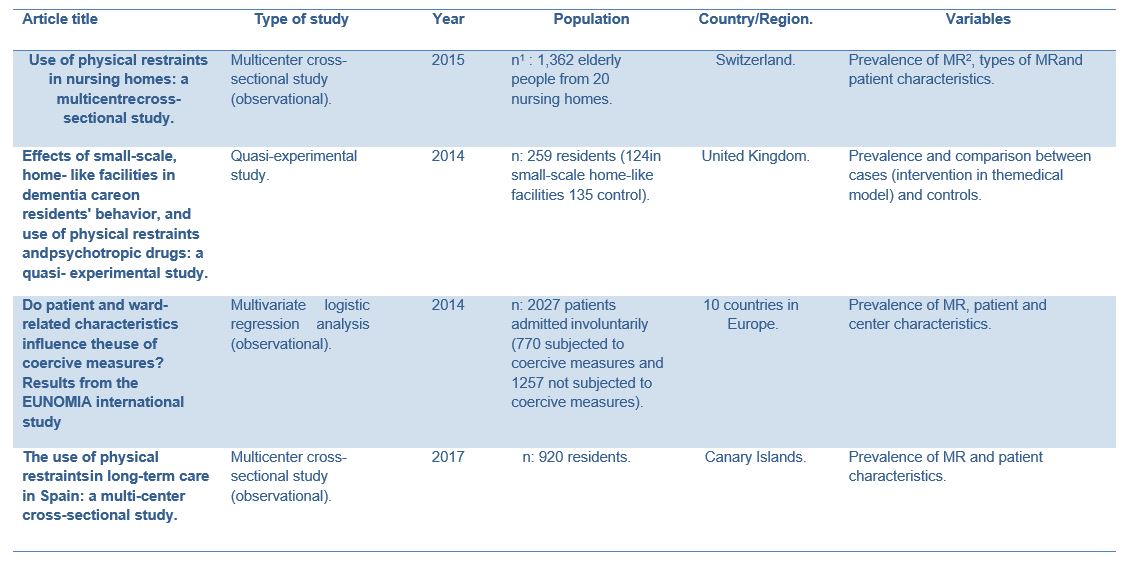

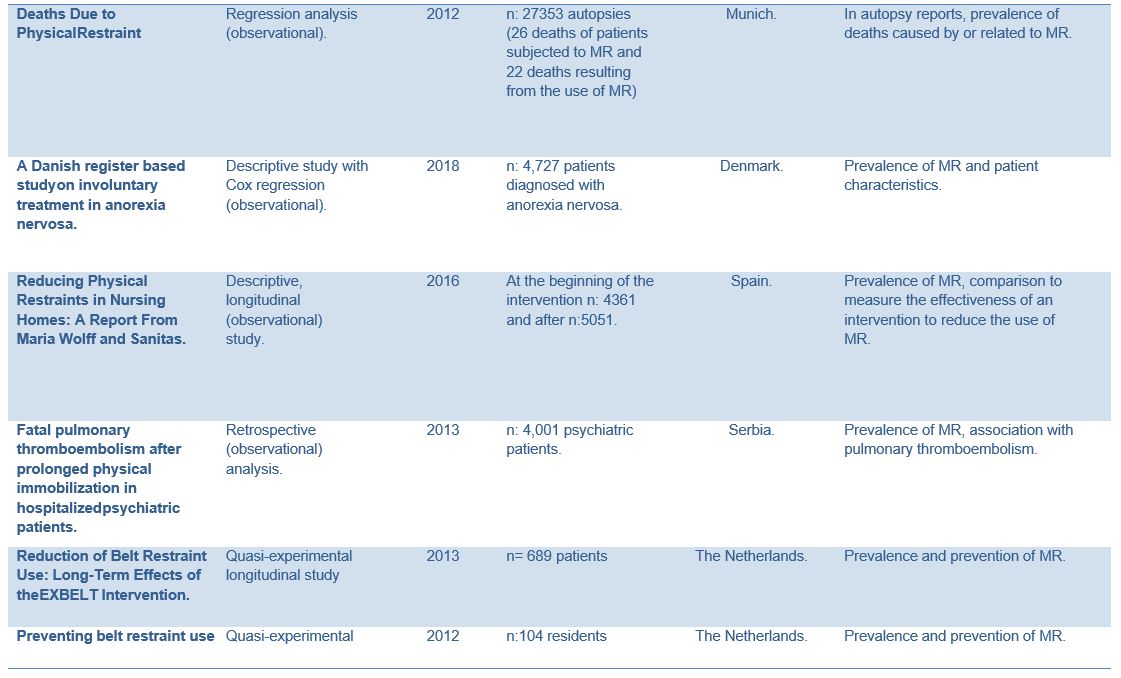

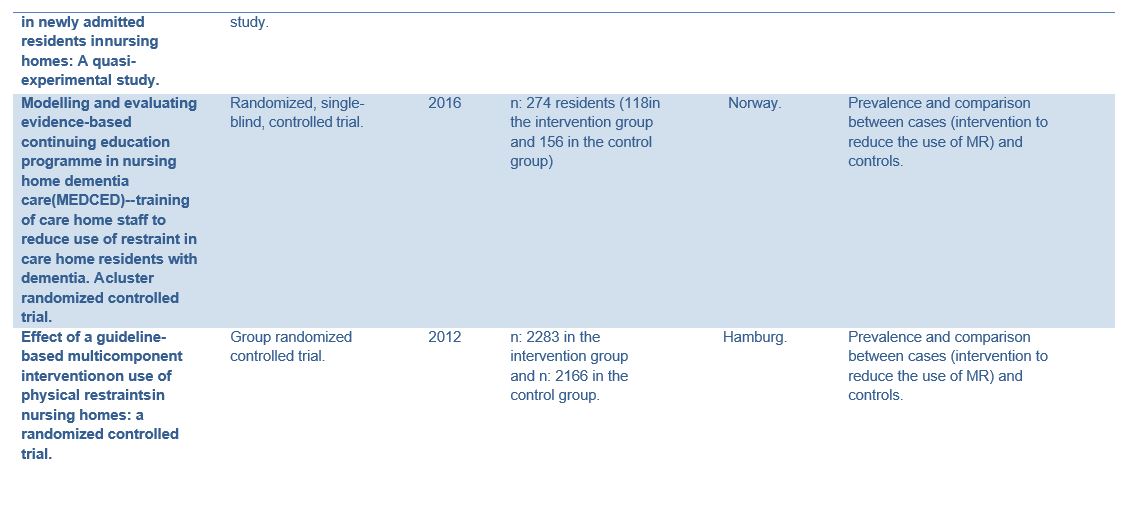

Se dividió la información en las variables que aparecen en la Tabla 1, agrupando posteriormente los resultados de los artículos en áreas de prevalencia, efectos y alternativas de la CM. No se presenta sesgo por el uso de estudios cuantitativos en los resultados y cualitativos en la discusión.

Tabla 1. Variables de interés de los artículos incluidos en los resultados de la revisión sistemática

Resultados

Tras la búsqueda realizada se han recogido los estudios encontrados hasta el 8 de marzo de 2021: En PubMed encontramos 112 registros, 1 en Web of Science y 5 en Scopus. La selección final para el análisis se ha compuesto de 20 trabajos (Figura 1).

Figura 1. Diagrama de flujo del proceso de búsqueda bibliográfica.

Prevalencia de la contención mecánica y efectos sobre el paciente

La contención mecánica (CM) representa un problema relevante en la práctica clínica por su prevalencia y efectos. Múltiples estudios han investigado las consecuencias negativas, deduciendo un interés creciente sobre el desarrollo de protocolos, programas y terapias para reducir o prevenir la CM.

Una investigación realizada en Suiza en 2015 sobre la CM en residencias, observó que la prevalencia de CM entre sus usuarios era de un 26,8% y que el tipo de CM más utilizado eran las barandillas laterales (20,3%). Dadas las altas tasas de CM, los autores destacaron la necesidad de una valoración individualizada para emplear la CM y abogaron por reducir su uso (13).

En Dinamarca en 2018 se estudió medidas de tratamiento en pacientes con anorexia nerviosa, siendo las medidas más comunes, después del aislamiento, la contención física (51,7%) y la contención mecánica (37,8%) (14).

En otro trabajo realizado en 2017 volvió a exponerse la prevalencia de la CM, en este caso en centros públicos de Canarias. Se observó que la prevalencia de los residentes con al menos una contención física era de 84,9%. El motivo principal del uso de CM fue la prevención de las caídas desde una cama o silla (94,2%). Por otro lado, se determinó que las personas con CM eran mayores y mostraron un mayor nivel de deterioro funcional, cognitivo y menor movilidad que aquellos sin CM. Además, el grado de deterioro se relacionaba directamente con la probabilidad de sufrir la contención. También se relacionaba la CM con el deterioro cognitivo (15).

En cuanto a otros efectos adversos, un trabajo sobre los efectos de la CM en 2013 en Serbia encontró una posible relación entre los tromboembolismos pulmonares y la inmovilización física de pacientes psiquiátricos hospitalizados (16). En otro estudio realizado en Múnich en 2012 analizó las muertes de pacientes en relación a la CM y demostró que 26 muertes en una muestra de 2027 usuarios se produjeron bajo los efectos de la CM. También se aludió a otras complicaciones: a corto plazo se asoció a pérdida de autonomía, libertad y dificultad en las relaciones sociales, mientras que, a largo plazo la CM producía atrofia de la musculatura o empeoramiento de la atrofia previa del paciente, asociándose también a trombosis venosa, estrés y efectos negativos sobre las habilidades cognitivas. Además, una aplicación incorrecta de las correas conllevaba lesiones, como abrasiones cutáneas, hematomas, etc. Asimismo, este trabajo observó que en psiquiatría era más frecuente su uso para prevenir autolesiones e intentos de suicidio y que las barreras laterales eran el método predominante en el ámbito de la geriatría (17). La CM es utilizada habitualmente en pacientes con demencia como prevención de caídas o lesiones. La reducción de la CM en estos casos puede causar aumento de la medicación antipsicótica, aunque no existen suficientes estudios que lo comprueben (18).

En 2014 se publicó un estudio con datos de 10 países europeos con pacientes psiquiátricos ingresados contra su voluntad. Se demostró que los pacientes tratados con la CM tuvieron niveles más altos de desconfianza, mientras que en los otros pacientes sin CM predominaban los síntomas depresivos y la ansiedad (19).

Prevención y alternativas

Varios estudios, como el realizado en Alemania en 2012, describieron el uso de intervenciones para reducir la CM y posteriormente compararon la eficacia de estos métodos. Este demostró que las intervenciones sobre la CM pueden reducir la tasa de CM de 31,5% a 22,6% (20).

La CM y los dilemas que plantea han sido puestos de manifiesto en otros estudios, como el publicado en 2016, que destacó el uso regular de CM en residencias como indicador de una baja calidad en los cuidados, ya que la CM suponía efectos secundarios físicos y psíquicos. Este trabajo se centró en la reducción de la CM en residencias de ancianos mediante la introducción de un programa de atención personalizada, entrenamiento y educación del personal, con el fin de eliminar de forma segura la CM. Según los datos, se logró reducir el uso de la CM del 18,1% al 1,6%, siendo aún mayor en el grupo de pacientes con demencia (de 29,1% a 2,2%) (21).

Entre otros métodos para disminuir la CM, en 2014 se publicó una investigación que comparaba la prevalencia de la CM en residencias de Reino Unido tras modificar el entorno de pacientes. Se objetivó un uso significativamente menor de CM (22). Es relevante en este campo, el estudio longitudinal realizado en 10 residencias donde se describieron los efectos del programa EXBELT sobre el uso de la CM, con énfasis en el uso de cinturones. El programa consistía en 4 componentes: cambios de política del uso de CM, programa educativo para las enfermeras, consultas y terapias alternativas. El uso de cinturones se redujo un 65% en 24 meses (23). El mismo programa se utilizó en un estudio en pacientes con demencia de las residencias de Países Bajos. Se demostró que las medidas EXBELT evitaban el uso de la CM en pacientes recién admitidos (24).

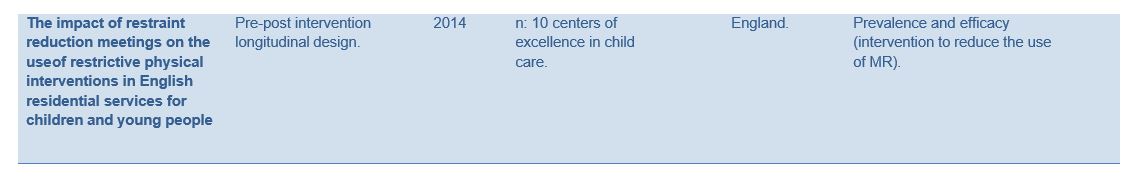

En 2014 fue publicado un estudio sobre la reducción en frecuencia y medidas de contención, aplicando el método de reuniones tras la CM en residencias inglesas de niños y adolescentes, con el fin de reducir y prevenir las futuras contenciones. La reducción total de todas las medidas de contención fue de 31,6% (25).

Según un estudio desarrollado en 2014, el factor preventivo más importante para la reducción de la CM era la formación a los trabajadores y enfermeras, otros factores como la terapia ambiental cognitiva y la atención centrada en el paciente no mostraron igual eficacia (26). Sin embargo, un trabajo desarrollado un año después, en unidades psiquiátricas de Noruega y Dinamarca, afirmó que había más factores con un efecto significativo en la prevención de la CM, como la participación de los pacientes, la revisión obligatoria y el uso de salas comunes. Las unidades en las que el personal llevaba un seguimiento de los casos individuales de CM demostraron que se reducía un 64% la prevalencia con respecto a centros en los que la evaluación se realizaba sólo en algunos casos (27).

Un estudio español realizado en 2015, observó que, tras la implementación del protocolo actualizado de la CM en el Hospital General de Málaga, se consiguió disminuir significativamente la duración de la contención, pero no su frecuencia (28). Posteriormente, en 2018 un estudio realizado en el sur de Alemania, analizó los resultados tras implementar una intervención para reducir los métodos coercitivos. Entre las acciones estaban: la identificación temprana de los pacientes en riesgo, un plan individualizado para el tratamiento psicofarmacológico de los pacientes, diseño del perfil de pacientes con alto riesgo de comportamientos violentos por un psicólogo, implicación de pacientes y familiares, inclusión de un terapeuta ocupacional para trabajar con la integración sensorial y un fisioterapeuta para facilitar la actividad física. El uso de CM y medicación involuntaria disminuyó considerablemente en comparación con los centros en los que no se implementó la intervención (29).

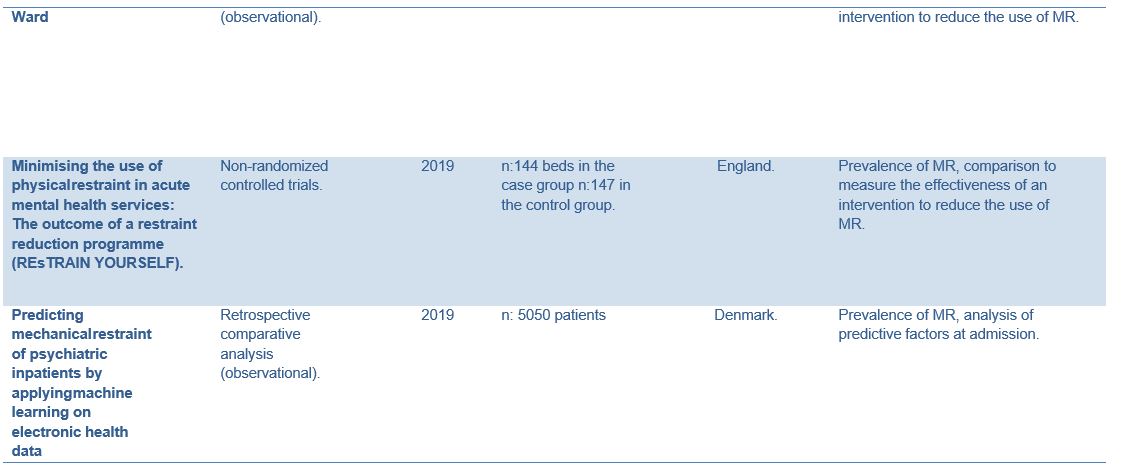

El enfoque multimodal de programas para la reducción de la CM demostró ser eficaz en la prevención, disminución de la frecuencia y duración de la CM en pacientes psiquiátricos (30). En 2019 se desarrolló el programa, REsTRAIN YOURSELF, que redujo la CM un 22% promedio. Se trató de la implementación de Six Core Strategies, un conjunto de técnicas alternativas a la CM. Como resultado, la ratio del uso de la CM fue significativamente menor en las salas de intervención (6,62 eventos/1000 (cama/día)), en comparación con las salas de control (9,38 eventos/1000 (cama/día)) (31). Por otra parte, estudios previos sugirieron que la identificación temprana de pacientes con alto riesgo de padecer la CM podría prevenir y reducir el uso de la misma. Factores de riesgo como esquizofrenia, trastornos mentales orgánicos, sexo masculino, vivir solo, admisión involuntaria; junto con los datos electrónicos obtenidos en las primeras horas tras la admisión, podrían ser identificados para crear un “sistema temprano de alarma” que guíe la intervención para prevenir y reducir la CM (32). El empleo de las estrategias del machine learning en la identificación de pacientes con riesgo a sufrir la CM muestra potencial para convertirse en una medida potente en prevención de la CM. Para valorar su eficacia, es necesario realizar más estudios en este ámbito.

Discusión

En los resultados de la revisión se apreció preocupación por los efectos de la CM y las alternativas que surgen debido a esto. La dicotomía entre beneficios y contraindicaciones incrementó los dilemas éticos entre pacientes y profesionales sanitarios. La disconformidad ante la práctica llevó a sus detractores a proponer medidas alternativas, como la práctica EXBELT (23), o la iniciativa REsTRAIN Yourself (33). Sin embargo, prevaleció el uso de CM en situaciones de tratamiento de dolor por considerarse la forma más positiva de tratar al paciente (34). Si el propósito principal es curar y evitar el dolor, ¿cuál es el método más adecuado?

La CM puede vulnerar los principios básicos de la bioética. Autonomía y justicia se vulneran al perder el paciente su derecho de autodeterminación, ya que la CM se suele aplicar contra su voluntad. La no maleficencia se quebranta mediante los efectos que genera la CM (lesiones cutáneas, daños pulmonares, trombosis venosa profunda y traumas psicológicos). La CM busca la beneficencia del paciente, aunque se vulneren el resto de principios (35). Dentro del personal sanitario surgen dilemas, aunque se considere beneficiosa la CM si se usa para evitar autolesiones, sin que ocurra lo mismo en cualquier otra situación. Además, influyen factores como la sobrecarga de trabajo, la condición clínica del paciente, la falta de alternativas, o la falta de protocolos para decidir si realmente se está generando un beneficio (34). Estos factores exigen una respuesta rápida, que puede producir un excesivo uso de medidas de contención, siendo el equilibrio entre los riesgos y la seguridad, efímero (36).

Existen factores subjetivos, como conocer al paciente para tratar de predecir su comportamiento, o incluso, reducir los riesgos para el personal, que influyen significativamente (37).

La CM debería usarse cuando sea absolutamente necesaria, para proteger al paciente y a quienes le rodean, siendo el último recurso y aplicado de la forma más segura posible para respetar la dignidad del paciente. En las revisiones posteriores, a los incidentes que sufren los pacientes tras usar la CM, se destaca la ética y filosofía del cuidado para mejorar la atención y contribuir a prevenir la inmovilización. Esta se basa en reconocer la vulnerabilidad, dependencia y dignidad de las personas. Sin tener en cuenta esto, no tiene cabida evaluar preferencias y necesidades de los pacientes como un objeto de estudio (38).

Actualmente, no existe una evidencia que permita determinar la efectividad de las alternativas sobre la CM para todos los casos, solo se puede contar con una evaluación temprana y estrategias preventivas (39). Lo que se puede afirmar, es que se pone en práctica con frecuencia. En España, en el año 2018, el 98% del personal sanitario encuestado usó la CM, pero el 82% pensaba que su entrenamiento era insuficiente. Por lo tanto, puede que muchos de los aspectos negativos de esta práctica no sean la falta de alternativas, sino la falta de formación del personal y de protocolos que sustenten dicha práctica (40) (Figura 2).

Figura 2. Efectos y nuevas estrategias de la contención mecánica.

Esta revisión ha tenido una serie de limitaciones: más de la mitad de los estudios incluidos eran de tipo observacional, que tienen un menor nivel de evidencia, además, no se ha podido realizar un meta análisis, ya que las variables que se recogen son distintas y las que no lo son, se miden de manera distinta entre los manuscritos.

Conclusión

La contención mecánica engloba métodos que limitan la movilidad de la persona, parcial o totalmente, empleando para ello diferentes dispositivos, como correas o cinturones. En los centros sanitarios se utiliza para garantizar la seguridad de los pacientes y de su entorno. Además, ha de ser aprobada y supervisada en todo momento por el personal sanitario. En Europa, la prevalencia del uso de contenciones es muy variable, los estudios apuntan a que no se ve influenciada por las características de organización de los centros y que el mayor motivo para su uso en las residencias es impedir las caídas, y las lesiones en los pacientes con demencia, mientras que en psiquiatría se emplea más en episodios de agitación o violencia. Se han detectado efectos negativos para el paciente como pérdida de autonomía y obstaculización de las relaciones sociales, aumento del deterioro cognitivo y funcional e incremento del riesgo de episodios tromboembólicos. Ulteriormente, las contenciones implican una pérdida de libertad.

Dados los efectos negativos, existen múltiples intervenciones para disminuir la prevalencia, tanto en residencias como en centros sanitarios y unidades de psiquiatría, incorporando medidas como la formación a los profesionales, la implicación de los pacientes y familiares, el registro sistemático de todos los casos en los que se emplea la contención, la utilización de salas y habitaciones comunes y no individuales, el trabajo multidisciplinar, el empleo de métodos calmantes no farmacológicos como la música, e incluso la elaboración de una valoración temprana de los posibles episodios de agitación. Todos estos programas han demostrado reducir significativamente el uso de la CM. Destacan la necesidad de una individualización y un enfoque multidisciplinar de estas medidas, dado que funcionan y benefician al paciente.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Sastre Rus M, Campaña Castillo F. Contención mecánica: definición conceptual. Rev Ene Enfermería [Internet]. 2014;8:1. Disponible en: https://ene-enfermeria.org

- Masters KJ. Physical restraint: A historical review and current practice. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47(1):52–5.

- Rubio Domínguez J. Contención mecánica de pacientes. Situación actual y ayuda para profesionales sanitarios. Rev Calid Asist. 2017;32(3):172–7.

- Europeo T, Noviembre DH. Convenio Europeo para la Protección de los Derechos Humanos y de las Libertades Fundamentales revisado de conformidad con el Protocolo n ° 11 completado por los Protocolos n ° 1 y 6. 1998;2:1–16.

- Pichon and Sajous v. Francia. Corte Europea de Derechos Humanos [Internet]. CEJIL, editor. 2011. 145 p. Disponible en: https://www.cejil.org

- López López MT, de Montalvo Jääskeläinen F, Alonso Bedate C, Bellver Capella V, Bellver Capella F, de los Reyes López M, et al. Consideraciones éticas y jurídicas sobre el uso de contenciones mecánicas y farmacológicas en los ámbitos social y sanitario [Internet]. Comité de Bioética de España. 2016. p. 46. Disponible en: https://www.comitedebioetica.es

- Bohorquez de Figueroa A, Carrascal S, Acosta S, Suárez J, Melo A, Pérez J, et al. Evolución del estado mental del paciente sometido a la contención mecánica. Rev cienc Cuid. 2010;7(1):29–34.

- Engberg J, Castle NG, McCaffrey D. Physical restraint initiation in nursing homes and subsequent resident health. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):442–52.

- Quintero-Uribe LC, Blanco-Arriola L, Zarrabeitia MT. Muertes provocadas por cinturones de contención en ancianos encamados. Rev Esp Med Leg. 2012;38(1):28–31.

- Syamsudin A, Fiddaroini FN, Heru MJA. Minimizing the Use of Restraint in Patients with Mental Disorders at a Mental Hospital: A Systematic Review. J Ners. 2020;14(3):283.

- López J, Ramos P, Gutiérrez J, Rexach L, Artaza I, Moreno N. Documento de consenso sobre Sujeciones Mecánicas y Farmacológicas. [Internet]. Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, editor. 2014. 203-218 p. Disponible en: https://www.segg.es

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):6.

- Hofmann H, Schorro E, Haastert B, Meyer G. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):1–8.

- Clausen L, Larsen JT, Bulik CM, Petersen L. A Danish register-based study on involuntary treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(11):1213–22.

- Estévez-Guerra GJ, Fariña-López E, Núñez-González E, Gandoy-Crego M, Calvo-Francés F, Capezuti EA. The use of physical restraints in long-term care in Spain: a multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):29.

- Stefanović V, Kuzmanović A, Stefanović S. Fatal pulmonary thromboembolism after prolonged physical immobilization in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70(10):903–7.

- Berzlanovich AM, Schöpfer J, Keil W. Deaths due to physical restraint. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(3):27–32.

- Testad I, Mekki TE, Førland O, Øye C, Tveit EM, Jacobsen F, et al. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)–training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(1):24–32.

- Kalisova L, Raboch J, Nawka A, Sampogna G, Cihal L, Kallert TW, et al. Do patient and ward-related characteristics influence the use of coercive measures? Results from the EUNOMIA international study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(10):1619–29.

- Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Gerlach A, Haut A, Haastert B, Möhler R, et al. Effect of a guideline-based multicomponent intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2177–84.

- Muñiz R, Gómez S, Curto D, Hernández R, Marco B, García P, et al. Reducing Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes: A Report From Maria Wolff and Sanitas. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(7):633–9.

- Verbeek H, Zwakhalen SMG, van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Kempen GIJM, Hamers JPH. Effects of small-scale, home-like facilities in dementia care on residents’ behavior, and use of physical restraints and psychotropic drugs: a quasi-experimental study. Int psychogeriatrics. 2014;26(4):657–68.

- Gulpers MJM, Bleijlevens MHC, Ambergen T, Capezuti E, van Rossum E, Hamers JPH. Reduction of belt restraint use: long-term effects of the EXBELT intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):107–12.

- Gulpers MJM, Bleijlevens MHC, Capezuti E, van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Hamers JPH. Preventing belt restraint use in newly admitted residents in nursing homes: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(12):1473–9.

- Deveau R, Leitch S. The impact of restraint reduction meetings on the use of restrictive physical interventions in English residential services for children and young people. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(4):587–92.

- Bak J, Zoffmann V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Brandt-Christensen M. Mechanical restraint in psychiatry: preventive factors in theory and practice. A Danish-Norwegian association study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014;50(3):155–66.

- Bak J, Zoffmann V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Siersma VD, Brandt-Christensen M. Comparing the effect of non-medical mechanical restraint preventive factors between psychiatric units in Denmark and Norway. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(6):433–43.

- Guzman-Parra J, Garcia-Sanchez JA, Pino-Benitez I, Alba-Vallejo M, Mayoral-Cleries F. Effects of a Regulatory Protocol for Mechanical Restraint and Coercion in a Spanish Psychiatric Ward. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(4):260–7.

- Højlund M, Høgh L, Bojesen AB, Munk-Jørgensen P, Stenager E. Use of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines in connection to minimising coercion and mechanical restraint in a general psychiatric ward. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(3):258–65.

- Guzman-Parra J, Aguilera Serrano C, García-Sánchez JA, Pino-Benítez I, Alba-Vallejo M, Moreno-Küstner B, et al. Effectiveness of a Multimodal Intervention Program for Restraint Prevention in an Acute Spanish Psychiatric Ward. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(3):233–41.

- Duxbury J, Baker J, Downe S, Jones F, Greenwood P, Thygesen H, et al. Minimising the use of physical restraint in acute mental health services: The outcome of a restraint reduction programme (‘REsTRAIN YOURSELF’). Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:40–8.

- Danielsen AA, Fenger MHJ, Østergaard SD, Nielbo KL, Mors O. Predicting mechanical restraint of psychiatric inpatients by applying machine learning on electronic health data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):147–57.

- Duxbury J, Thomson G, Scholes A, Jones F, Baker J, Downe S, et al. Staff experiences and understandings of the REsTRAIN Yourself initiative to minimize the use of physical restraint on mental health wards. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(4):845–56.

- Sønderskov ML, Hallas P. The use of “brutacaine” in Danish emergency departments. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013 Oct;20(5):370–2.

- Zaami S, Rinaldi R, Bersani G, Marinelli E. Restraints and seclusion in psychiatry: striking a balance between protection and coercion. Critical overview of international regulations and rulings. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55(1):16–23.

- Cusack P, McAndrew S, Cusack F, Warne T. Restraining good practice: Reviewing evidence of the effects of restraint from the perspective of service users and mental health professionals in the United Kingdom (UK). Int J Law Psychiatry. 2016;46:20–6.

- Perkins E, Prosser H, Riley D, Whittington R. Physical restraint in a therapeutic setting; a necessary evil? Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35(1):43–9.

- Hammervold UE, Norvoll R, Vevatne K, Sagvaag H. Post-incident reviews-a gift to the Ward or just another procedure? Care providers’ experiences and considerations regarding post-incident reviews after restraint in mental health services. A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):499.

- Fariña-López E, Estévez-Guerra GJ, Polo-Luque ML, Hanzeliková Pogrányivá A, Penelo E. Physical Restraint Use With Elderly Patients: Perceptions of Nurses and Nursing Assistants in Spanish Acute Care Hospitals. Nurs Res. 2018;67(1):55–9.

- Freeman S, Yorke J, Dark P. The management of agitation in adult critical care: Views and opinions from the multi-disciplinary team using a survey approach. Intensive Crit care Nurs. 2019;54:23–8.

Effects of Mechanical Restraint and Bioethical Implications in Europe: A Systematic Review

Introduction

Mechanical restraint (MR) is a fairly common practice despite the controversy surrounding its negative effects and the bioethical dilemmas it raises. The objective of this review is to determine the prevalence and effects of MR in patients, as well as the ethical dilemmas that its use poses for healthcare professionals, while shedding light on prevention and alternative techniques derived from efforts to reduce its use.

Methodology

A systematic search was performed from 2012 to the present in three databases: PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus. Studies related to the health field and to the effects, prevention and alternatives to MR were selected. Excluded studies were: systematic reviews, qualitative studies, studies tested in animals, studies in a language other than English or Spanish, unfinished studies and studies without online full-text access.

Results

Of 115 records found, 20 studies that met the established eligibility criteria were included. The negative effects go from loss of autonomy to risk of pulmonary thromboembolism. The most commonly used methods of prevention and reduction of MR include professional training, multidisciplinary work and individualized treatment plans. The implementation of new strategies based on the use of electronic systems for early identification of risk factors could contribute to prevent MR, although further studies are needed.

Conclusions

Past studies focused mainly on the effects of MR, whereas more recent studies show a clear focus on MR reduction and prevention. The number of new articles on the use of MR is limited due to emerging topics.

Keywords: mechanical restraint, effects, procedures, therapies.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the mechanical restraint (MR) as extraordinary methods for therapeutic purposes, only acceptable in emergency situations in which there is an urgent or immediate threat to the life or physical integrity of patients or third parties and which cannot be averted by other therapeutic means. MR began to be used approximately 300 years ago; mainly in people who were difficult to control (2) in order to prevent self-harm and physical harm to third parties. Initially, the use of MR was not considered a violation of human rights and was legally approved, so it was widely used in psychiatric hospitals. However, progressive social awareness and greater visibility of the reality of many patients led to discussion of the legal and ethical dilemmas that its use poses (1).

MR can be total if it limits most of the patient’s movements or partial if it limits only the mobility of some limbs or the trunk. MR differs from physical restraint lie in that the latter involves bodily force without using any devices (1,3).

The intention to reduce the use of MR is reflected in laws, principles and amendments related to this practice. One of the problems faced by patients and professionals is the lack of a common legal framework. At the European level, there are references to MR in documents that legislate on human rights such as the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (4). These references are illustrated in practice, where the European Court of Human Rights condemn degrading treatment, opposite to what the Convention says, but it does not condemn physical or mechanical restraints itself (5).

In Spain, Law 41/1986 is directed to those actions that allow the right to healthcare to be effective, without explicitly mentioning MR. Nevertheless, Law 1/1999 of March 31 of Andalusia mentions MR in relation to residential centers, making it necessary for measures depriving users of freedom of movement to be approved by the judicial authority. Moreover, Law 41/2002 established informed consent as essential except in situations where it is necessary to preserve the health and life of the patient (6).

The current indications for the use of MR, according to most protocols, are as follows:

- When there is a risk to the patient’s physical integrity such as falling down or self-harm.

- In the event of physical threat from the patient to third parties.

- In therapeutic settings, as a method to avoid starting medication or catheters, or in situations that require rest and this cannot be achieved in any other way.

MR is associated in some studies with negative effects on both the physical and mental health of patients (7). In addition, it exposes healthcare professionals to some ethical conflicts arising from the confrontation between patients’ rights and their healthcare duties (8-10). For all these reasons, according to recent studies, there has been an increase in the identification of predisposing factors, the study of the effects of MR and the use of alternative methods such as environmental modification or verbal reassurance (6).

Existing protocols are insufficient and should be expanded to reduce the ethical dilemmas arising from the use of MR, supported by a legal framework that responds to these needs (11). For these reasons, together with its clinical relevance, it is important to know the factors that pose a greater or lesser risk of using MR and the alternative methods available. The ambiguity of the current legislation, the heterogeneity of the published research and the actual bioethical dilemmas involved make it necessary to take a highly individualized and a multidisciplinary approach to this topic.

The aim of this systematic review is to determinate the consequences of MR use, both the negative effects on the physical and mental health of patients and the ethical dilemmas that healthcare professionals may face. Other objectives are to delimitate the legal framework of MR and the situations in which it is currently used in specific contexts that is used and to present alternative techniques to replace or prevent the use of MR.

Methodology

After searching three databases (PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus) between February and March, 2021, literature published in the last ten years using the following search equation: “Effects AND Physical Restraint AND Europe”. The results were analyzed by all the authors using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (12).The inclusion criteria were: to appear in the selected databases with the search equation used and to deal with MR. The exclusion criteria were: not belonging to the public health field; not dealing with the effects or prevalence of MR or prevention methods and alternatives to its use; to test in animals; being written in a language other than English or Spanish, not having online full-text access, not being qualitative studies; research projects with pending results or systematic reviews.

The information was divided into the variables listed in Table 1, subsequently grouping the into three MR areas: prevalence field, effects and alternatives. There is no possibility of bias due to the use of quantitative studies in the results and qualitative studies in the discussion.

Table 1. Variables of interest of the articles included in the results of this systematic review.

1 N: sample size.

2 CM: Mechanical containment.

Results

Once the search was performed, the studies found up to 8 March, 2021 were included: 112 records in PubMed, 1 record in Web of Science and 5 records in Scopus. The final selection for analysis consisted of 20 studies (Figure 1).

Prevalence of mechanical restraint and effects on patients

MR represents a relevant problem in clinical practice due to its prevalence and effects. Several studies have investigated its negative effects, indicating a growing interest in the development of protocols, programs and therapies to reduce or prevent MR. Research conducted in Switzerland in 2015 on MR in nursing homes found that the prevalence of MR among users was 26.8% and that the most commonly used type of MR was bilateral bedrails (20.3%). Given the high rates of MR, the authors highlighted the need for individualized assessment to use MR and advocated reducing its use (13).

In Denmark, in2018, treatment measures in patients with anorexia nervosa were studied. It was found that, after isolation, the most common measures were physical restraint (51.7%) and mechanical restraint (37.8%) (14).

The prevalence of MR was proved again in another study performed in 2017, in this case in public institutions in the Canary Islands (Spain). The prevalence of residents with at least one form of physical restraint was 84.9%. The main reason for the use of MR was the prevention of falls from beds/chairs (94.2%). In addition, it was determined that people subjected to MR were older and showed a higher level of functional and cognitive impairment and less mobility than those without MR. The degree of impairment was directly related to the probability of suffering restraint. MR was also related to cognitive impairment (15).

Regarding other adverse effects, a 2013 study conducted in Serbia on the effects of the MR suggested a possible association between pulmonary thromboembolisms and the physical immobilization of hospitalized psychiatric patients (16). Another study conducted in Munich in 2012 analyzed patient deaths in relation to MR, showing that 26 deaths in a sample of 2017 users occurred under MR. Additionally, reference was made to other complications such as: in the short term, it was associated with loss of autonomy, freedom and difficulty in social relationships; in the long term, MR caused muscular atrophy or worsened existing atrophy and was also associated with venous thrombosis, stress and negative effects on cognitive abilities. Moreover, incorrect application of the straps led to injuries such as skin abrasions or hematomas. It was also found that, in psychiatry, MR was commonly used to prevent self-harm and suicide attempts. The side rails were the predominant method for care-home residents (17). MR is commonly used in patients with dementia to prevent falls or injuries. Reducing the use MR in these cases may result in increased use of antipsychotic medication, although there are not sufficient studies that can prove this (18).

In 2010 a study was published with data from 10 European countries on psychiatric patients admitted against their will. It showed that patients subjected to MR had higher levels of mistrust, whereas depressive symptoms and anxiety predominated in patients not subjected to it (19).

Prevention and alternatives

Several studies, such as one conducted in Germany in 2012, described the use of interventions to reduce the use of MR and compared the efficiency of these methods. This study indicated that alternative methods to MR can reduce its use from 31.5% to 22.6% (20).

The use of MR and the dilemmas it poses have been highlighted in various studies. Research conducted in 2016 showed that regular use of MR in nursing homes can be an indicator of poor quality of care due to its physical and psychological side-effects. This work focused on reducing the use of MR in nursing homes by introducing a personalized assistance program and educational training of healthcare professionals to safely prevent the use of MR. According to the data, the use of MR was reduced from 18.1% to 1.6%, being even higher in patients with dementia (from 29.1% to 2.2%).

Another study published in 2014, which compared the prevalence of MR in nursing homes in the UK after modifying the patients’ surroundings, showed a significant decrease in its use. (22) Also, a longitudinal study conducted on 10 nursing homes on the use of MR describing the effects of the EXBELT program focused on the use of belts. The program emphasized 4 areas: policy changes regarding MR, an educational program for nurses, inquiries and alternative therapies. Belt use was reduced by 65% in 24 months (23). The same program was investigated in another study on patients with dementia in nursing homes in the Netherlands, proving that EXBELT measures prevented the use of MR in newly admitted patients (24).

A study was published in 2014, which consisted in the reduction of the frequency and measures of restraint, based on maintaining professional meetings after each MR in English nursing homes for kids and teenagers, with the aim of reducing and preventing future restraints. The study showed a 31.6 decrease of the total use of MR (25).

According to a study conducted in 2014, the most important preventive factor for the reduction of MR was instruction of health workers and nurses, while cognitive milieu therapy and patient-centered care showed to be less productive (26). Nevertheless, a study carried out a year later in psychiatric units in Norway and Denmark showed that there were other factors with a significant effect in the preventing the use MR, such as patient involvement, mandatory review and no crowding. Units that followed individual monitoring of MR cases showed a 64% reduction in prevalence compared with facilities in which monitoring was carried out just in some cases (27).

A study carried out in Spain in 2015 showed that following the implementation of the updated MR protocol at the General Hospital of Málaga, the duration of restraints was significantly decreased, but not its frequency (28). In 2018 a study carried out in southern Germany analyzed the results after the implementation of an intervention to reduce coercive measures. Among these actions were: early identification of patients at risk, an individualized contingency plan on relational and psychopharmacological treatment of patients, the involvement of patients and relatives, incorporation of an occupational therapist to work with sensory integration and a physiotherapist to facilitate physical activity. The use of MR and involuntary medication decreased remarkably in contrast to centers where this intervention was not implemented (29).

The multi-modal approach to MR programs proved to be efficient in prevention, as well as in decreasing the frequency and duration of MR in psychiatric patients. (30) The program REsTRAIN YOURSELF, developed in 2019, decreased MR by an average of 22%. It involved the implementation of Six Core Strategies, a set of alternative techniques to MR. As a result, the ratio of the use MR was significantly lower in intervention rooms (6.62 event/1000 [bed/day]) as compared to control rooms (9.38 event/1000 [bed/day]). Furthermore, previous studies suggested that early identification of patients at high risk for MR could prevent and reduce its use. Risk factors such as schizophrenia, organic mental disorders, being male, living alone and involuntary admission, together with electronic data obtained within the first hours after admission might be identified in order to create an “early warning system” to guide intervention to prevent or reduce MR. (32) The use of machine learning strategies in the identification of patients at risk for MR has the potential to become a powerful tool to prevent MR. Further studies are needed to assess its efficiency.

Discussion

The results of the review showed concern about the effects of MR and the potential alternatives to its use. The dichotomy between benefits and contraindications posed ethical dilemmas for patients and healthcare professionals. Dissatisfaction with its use led its detractors to propose alternative measures, such as the EXBELT practice (23), or the REsTRAIN Yourself initiative (33). However, the use of MR in pain management situations prevailed as the most effective way to treat patients (34). If the main purpose is avoiding or treating pain, what is the most appropriate method?

MR may violate the basic principles of bioethics. Autonomy and justice are compromised when the patient loses the right to self-determination, since MR is usually applied against the patient’s will. Non-maleficence is violated by the effects generated by MR (skin lesions, lung damage, deep vein thrombosis and psychological trauma). MR seeks the beneficence of the patient, even if the rest of the principles are violated (35). Health professionals face dilemmas when MR is used for anything other than preventing self-harm. In addition, factors such as work overload, the clinical condition of the patient, the lack of alternatives to its use, or the lack of protocols for deciding whether it will really benefit the patient also influence the use of MR (34). These factors demand a rapid response, which may lead to excessive use of restraint measures, the balance between risk and safety being ephemeral (36). In addition, subjective factors such as knowing the patient to try to predict her behavior or even to reduce risks to healthcare professionals can significantly influence the use of MR (37).

MR should be used when absolutely necessary, to protect the patient and those around him. It should be the last resort and applied as safely as possible to respect the patient’s dignity. In follow-ups after the use of MR, the ethics and philosophy of care is highlighted to improve care and contribute to prevent immobilization. This is based on recognizing the vulnerability, dependence and dignity of individuals. Without taking this into account, there is no place for assessing patient preferences and needs as an object of study (38).

Currently, there is no evidence to determine the effectiveness of alternatives to MR for all cases, only early assessment and preventive strategies (39). What can be established, however, is that it is frequently put into practice. In Spain, in 2018, 98% of healthcare professionals surveyed used MR of which 82% thought that their training was insufficient. Therefore, many of the negative effects of this practice may stem from a lack of training of healthcare professionals and the absence of protocols on its use (40) (Figure 2).

This systematic review has a number of limitations. More than half of the studies included were observational, which have a lower level of evidence. Also, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis, since the variables collected were different and those that were not were measured differently among the manuscripts (40).

Conclusion

MR encompasses methods that limit a person’s mobility, partially or totally, using different devices such as straps or belts. In healthcare facilities, it is used to ensure the safety of patients and third parties. The use of MR must be approved and supervised at all times by healthcare professionals. In Europe, its prevalence varies greatly. Studies indicate that its use is not determined by the organizational characteristics of healthcare facilities and that its use in nursing homes is to prevent injuries and falls in patients with dementia, while in psychiatric units it is used in episodes of agitation or violence. Among the negative effects of its use are loss of autonomy and difficulty in social relationships, increased cognitive and functional impairment and an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Finally, restraints imply a lack of freedom for the patient.

Given the negative effects of using MR, there are various interventions to decrease its prevalence in healthcare facilities, nursing homes and psychiatric units. Recommendations include the training of healthcare professionals, the implication of patients and their relatives, the systematic register of all cases in which restraints are used, the use of common rooms instead of individual ones, multidisciplinary work, the use of non-pharmacological soothing methods such as music therapy, or the development of an early assessment of possible episodes of agitation. All these programs have been shown to significantly reduce the use of MR. They emphasize the need for individualization and a multidisciplinary approach to these measures, as they are effective and beneficial for patients.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sastre Rus M, Campaña Castillo F. Contención mecánica: definición conceptual. Rev Ene Enfermería [Internet]. 2014;8:1. Disponible en: https://ene-enfermeria.org

- Masters KJ. Physical restraint: A historical review and current practice. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47(1):52–5.

- Rubio Domínguez J. Contención mecánica de pacientes. Situación actual y ayuda para profesionales sanitarios. Rev Calid Asist. 2017;32(3):172–7.

- Europeo T, Noviembre DH. Convenio Europeo para la Protección de los Derechos Humanos y de las Libertades Fundamentales revisado de conformidad con el Protocolo n ° 11 completado por los Protocolos n ° 1 y 6. 1998;2:1–16.

- Pichon and Sajous v. Francia. Corte Europea de Derechos Humanos [Internet]. CEJIL, editor. 2011. 145 p. Disponible en: https://www.cejil.org

- López López MT, de Montalvo Jääskeläinen F, Alonso Bedate C, Bellver Capella V, Bellver Capella F, de los Reyes López M, et al. Consideraciones éticas y jurídicas sobre el uso de contenciones mecánicas y farmacológicas en los ámbitos social y sanitario [Internet]. Comité de Bioética de España. 2016. p. 46. Disponible en: https://www.comitedebioetica.es

- Bohorquez de Figueroa A, Carrascal S, Acosta S, Suárez J, Melo A, Pérez J, et al. Evolución del estado mental del paciente sometido a la contención mecánica. Rev cienc Cuid. 2010;7(1):29–34.

- Engberg J, Castle NG, McCaffrey D. Physical restraint initiation in nursing homes and subsequent resident health. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):442–52.

- Quintero-Uribe LC, Blanco-Arriola L, Zarrabeitia MT. Muertes provocadas por cinturones de contención en ancianos encamados. Rev Esp Med Leg. 2012;38(1):28–31.

- Syamsudin A, Fiddaroini FN, Heru MJA. Minimizing the Use of Restraint in Patients with Mental Disorders at a Mental Hospital: A Systematic Review. J Ners. 2020;14(3):283.

- López J, Ramos P, Gutiérrez J, Rexach L, Artaza I, Moreno N. Documento de consenso sobre Sujeciones Mecánicas y Farmacológicas. [Internet]. Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, editor. 2014. 203-218 p. Disponible en: https://www.segg.es

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):6.

- Hofmann H, Schorro E, Haastert B, Meyer G. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):1–8.

- Clausen L, Larsen JT, Bulik CM, Petersen L. A Danish register-based study on involuntary treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(11):1213–22.

- Estévez-Guerra GJ, Fariña-López E, Núñez-González E, Gandoy-Crego M, Calvo-Francés F, Capezuti EA. The use of physical restraints in long-term care in Spain: a multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):29.

- Stefanović V, Kuzmanović A, Stefanović S. Fatal pulmonary thromboembolism after prolonged physical immobilization in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70(10):903–7.

- Berzlanovich AM, Schöpfer J, Keil W. Deaths due to physical restraint. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(3):27–32.

- Testad I, Mekki TE, Førland O, Øye C, Tveit EM, Jacobsen F, et al. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)–training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(1):24–32.

- Kalisova L, Raboch J, Nawka A, Sampogna G, Cihal L, Kallert TW, et al. Do patient and ward-related characteristics influence the use of coercive measures? Results from the EUNOMIA international study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(10):1619–29.

- Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Gerlach A, Haut A, Haastert B, Möhler R, et al. Effect of a guideline-based multicomponent intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2177–84.

- Muñiz R, Gómez S, Curto D, Hernández R, Marco B, García P, et al. Reducing Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes: A Report From Maria Wolff and Sanitas. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(7):633–9.

- Verbeek H, Zwakhalen SMG, van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Kempen GIJM, Hamers JPH. Effects of small-scale, home-like facilities in dementia care on residents’ behavior, and use of physical restraints and psychotropic drugs: a quasi-experimental study. Int psychogeriatrics. 2014;26(4):657–68.

- Gulpers MJM, Bleijlevens MHC, Ambergen T, Capezuti E, van Rossum E, Hamers JPH. Reduction of belt restraint use: long-term effects of the EXBELT intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):107–12.

- Gulpers MJM, Bleijlevens MHC, Capezuti E, van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Hamers JPH. Preventing belt restraint use in newly admitted residents in nursing homes: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(12):1473–9.

- Deveau R, Leitch S. The impact of restraint reduction meetings on the use of restrictive physical interventions in English residential services for children and young people. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(4):587–92.

- Bak J, Zoffmann V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Brandt-Christensen M. Mechanical restraint in psychiatry: preventive factors in theory and practice. A Danish-Norwegian association study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014;50(3):155–66.

- Bak J, Zoffmann V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Siersma VD, Brandt-Christensen M. Comparing the effect of non-medical mechanical restraint preventive factors between psychiatric units in Denmark and Norway. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(6):433–43.

- Guzman-Parra J, Garcia-Sanchez JA, Pino-Benitez I, Alba-Vallejo M, Mayoral-Cleries F. Effects of a Regulatory Protocol for Mechanical Restraint and Coercion in a Spanish Psychiatric Ward. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(4):260–7.

- Højlund M, Høgh L, Bojesen AB, Munk-Jørgensen P, Stenager E. Use of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines in connection to minimising coercion and mechanical restraint in a general psychiatric ward. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(3):258–65.

- Guzman-Parra J, Aguilera Serrano C, García-Sánchez JA, Pino-Benítez I, Alba-Vallejo M, Moreno-Küstner B, et al. Effectiveness of a Multimodal Intervention Program for Restraint Prevention in an Acute Spanish Psychiatric Ward. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(3):233–41.

- Duxbury J, Baker J, Downe S, Jones F, Greenwood P, Thygesen H, et al. Minimising the use of physical restraint in acute mental health services: The outcome of a restraint reduction programme (‘REsTRAIN YOURSELF’). Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:40–8.

- Danielsen AA, Fenger MHJ, Østergaard SD, Nielbo KL, Mors O. Predicting mechanical restraint of psychiatric inpatients by applying machine learning on electronic health data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):147–57.

- Duxbury J, Thomson G, Scholes A, Jones F, Baker J, Downe S, et al. Staff experiences and understandings of the REsTRAIN Yourself initiative to minimize the use of physical restraint on mental health wards. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(4):845–56.

- Sønderskov ML, Hallas P. The use of “brutacaine” in Danish emergency departments. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013 Oct;20(5):370–2.

- Zaami S, Rinaldi R, Bersani G, Marinelli E. Restraints and seclusion in psychiatry: striking a balance between protection and coercion. Critical overview of international regulations and rulings. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55(1):16–23.

- Cusack P, McAndrew S, Cusack F, Warne T. Restraining good practice: Reviewing evidence of the effects of restraint from the perspective of service users and mental health professionals in the United Kingdom (UK). Int J Law Psychiatry. 2016;46:20–6.

- Perkins E, Prosser H, Riley D, Whittington R. Physical restraint in a therapeutic setting; a necessary evil? Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35(1):43–9.

- Hammervold UE, Norvoll R, Vevatne K, Sagvaag H. Post-incident reviews-a gift to the Ward or just another procedure? Care providers’ experiences and considerations regarding post-incident reviews after restraint in mental health services. A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):499.

- Fariña-López E, Estévez-Guerra GJ, Polo-Luque ML, Hanzeliková Pogrányivá A, Penelo E. Physical Restraint Use With Elderly Patients: Perceptions of Nurses and Nursing Assistants in Spanish Acute Care Hospitals. Nurs Res. 2018;67(1):55–9.

- Freeman S, Yorke J, Dark P. The management of agitation in adult critical care: Views and opinions from the multi-disciplinary team using a survey approach. Intensive Crit care Nurs. 2019;54:23–8.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Poncela-Díaz J. B., Pacheco-Nunes M, Giménez-Gironda E, Gállová L. Efectos de la contención mecánica e implicaciones bioéticas en Europa: una revisión sistemática. AMU. 2021; 3(1):92-111