Violeta De Pablos-Florido 1; Paula María Córdoba-Peláez 2; Paula María Jiménez-Gutiérrez 1

1 Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves (Granada)

2 Facultad de Ciencias (Bioquímica), Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Eva Aguilera-Parejo 4; Rania Bouanane-Hamed 4; Daniel Carmona-Molero 5; Juan Luis Ruiz-García 4; Sheila Vázquez-Ledo 6; David Vilas-Antelo 4

4 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

5 Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Córdoba (UCO)

6 Faculty of Translation, University of Salamanca (USAL)

Introducción

La persistencia de secuelas tras la COVID-19 es muy habitual pasados catorce días de la infección aguda. Se ha propuesto el término Long-COVID para hacer referencia al conjunto de dolencias secundarias a la infección por el virus SARS-CoV-2 que continúan o aparecen tras la fase aguda. Una secuela de las descritas es el dolor persistente sin afectación orgánica demostrada. Esta revisión sistemática pretende identificar las secuelas dolorosas más notificadas y su incidencia.

Métodos

Se realizó una búsqueda de artículos que documentaran dolor como consecuencia de la COVID-19. Las bases de datos consultadas fueron PubMed/Medline, Scopus y Web of Science. Además, se seleccionaron artículos citados en las referencias de artículos relevantes. En función de criterios de inclusión y exclusión detallados, tres investigadoras independientes llevaron a cabo la selección. Todos los artículos publicados antes del 11 de marzo de 2021 fueron incluidos. Esta revisión sistemática siguió la guía PRISMA.

Resultados

Fueron identificadas un total de 588 publicaciones, de las cuales once cumplieron criterios de inclusión. La cefalea fue la secuela dolorosa más frecuentemente reportada, con una prevalencia de hasta el 44 % en algunas series de casos. Se ha notificado dolor articular (19 %-31 %) y dolor torácico post COVID-19 (6 %- 28 %). El dolor de garganta persistente se reportó en el 32 % de los pacientes, así como dolor generalizado, que se ha observado hasta un 59 % de los casos. La polineuropatía del paciente que requirió ingreso en UCI fue notificada adicionalmente. El SARS-CoV-2 ocasiona daños a nivel de la microcirculación capilar, generando hipoxia tisular e inflamación; con el consecuente aumento de las secuelas dolorosas de tipo vasculo-isquémico e inflamatorio.

Conclusiones

La COVID-19 produce secuelas dolorosas de diversa índole. Se requieren estudios posteriores para filiar las características de los distintos tipos de dolor. Esto permitirá un manejo sintomatológico adecuado y una optimización de los recursos disponibles para hacer frente a los retos que la actual pandemia supone para las distintas áreas asistenciales.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus, dolor, secuelas dolorosas, Long- COVID, post-COVID, COVID persistente.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, pain, painful sequelae, long-COVID, post-COVID, persistent COVID.

Introducción

Desde el primer caso publicado por la COVID-19 en Wuhan (1) el 31 de diciembre de 2019, a día de 21 de marzo de 2021 son ciento dieciséis millones (2) las personas que se han contagiado. Muchas no recuperan la salud completamente, sino que sufren a largo plazo dolencias inespecíficas persistentes. Se conoce aún poco de estos efectos (3). Se reportan con elevada frecuencia casos de fatiga, cefalea, dificultades para concentrarse, caída del cabello y disnea (3, 12, 18). Por este motivo se ha sugerido el término Long-COVID, para aglutinar todas esas secuelas que surgen dos semanas después de haber pasado la enfermedad (4, 8).

Se ha demostrado que la presencia y la gravedad de los síntomas somáticos durante la infección aguda se correlacionan estrechamente con el desarrollo posterior de fatiga crónica y dolor (11, 25). En la experiencia clínica cotidiana de los últimos meses en el Sistema Andaluz de Salud (SAS), se ha observado un aumento de la afluencia a los centros sanitarios de pacientes con síntomas persistentes de la COVID-19. Dichos síntomas restan calidad de vida, son difíciles de filiar en su diagnóstico y no remiten fácilmente con los tratamientos habituales (5). De todos ellos, los síntomas más destacados son las mialgias, dolor referido e hiperalgesia generalizada (17). Se manifiesta en distintas localizaciones, tanto a nivel cefálico (20) como en tórax o en miembros (15). Además, responde a características variables: el mecanismo causal es desconocido tras descartar organicidad, aunque se está estudiando; y solo se asocia al hecho de padecer convalecencia tras la COVID-19 (8).

Se desconoce si la COVID-19 causará un aumento en el dolor crónico de nueva aparición. El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática fue recopilar ampliamente los datos reportados sobre el dolor como secuela de la COVID-19, y como objetivo secundario analizar si ha aumentado la incidencia de dolor crónico post-COVID en la pandemia. Consideramos de interés evaluar en futuros estudios los patrones del dolor crónico post-COVID; así como sus factores de riesgo, intensidad, características, y respuesta a los tratamientos utilizados actualmente.

Métodos

Se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de la literatura, realizada por tres investigadoras independientes (VPF, PCP y PJG). Las bases de datos consultadas fueron Pubmed, Scopus y Web of Science, con fecha de corte el 11 de marzo de 2021 para la selección de artículos. En aras de aumentar la sensibilidad de la búsqueda, también fue revisada la bibliografía citada en los artículos finalmente seleccionados. Se siguió una estrategia basada en la guía PRISMA (24). Los términos de búsqueda fueron: ‘COVID-19’ ‘long*’ y ‘pain’, unidos por el operador booleano ‘AND’.

Estrategia de búsqueda y criterios de selección

Se identificaron las publicaciones disponibles en lengua inglesa o española. Se seleccionaron los artículos que analizan datos de pacientes que aquejaran síntomas de dolor pasadas dos semanas de la infección aguda confirmada por SARS-CoV-2. Se incluyeron desde pacientes ambulatorios que no requirieron ingreso, hasta aquellos que requirieron ingreso en Unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI). Se trabajó únicamente con datos sobre población adulta. Fueron incluidos estudios observacionales de cohortes prospectivas, retrospectivas y transversales; así como revisiones sistemáticas y metanálisis. Los títulos y resúmenes de los artículos encontrados en las distintas bases de datos tras aplicar la ecuación de búsqueda fueron analizados sistemáticamente por investigadoras independientes. Los artículos que cumplían criterios de inclusión fueron revisados por completo y conjuntamente por tres investigadoras. Finalmente, se debatió el acuerdo o discrepancia en la inclusión de todos los estudios.

Criterios de inclusión y exclusión

Se excluyeron las publicaciones con idioma diferente al inglés o español, y cuya población a estudio fuera niños (menores de 18 años) y embarazadas. Se consideró como secuela persistente de la COVID-19 toda sintomatología secundaria a esta pasadas al menos dos semanas después de la fase aguda. Se rechazaron los estudios con tamaño muestral inferior a 50 individuos.

Extracción de datos de los artículos incluidos

Las referencias encontradas sobre la búsqueda sistemática fueron importadas al gestor bibliográfico Zotero. Después de la eliminación de duplicados, una sola carpeta de referencias fue generada. Se seleccionó a partir de los artículos seleccionados la siguiente información: número de sujetos estudiados, el país donde se recogieron los datos, edad media, sexo, el contexto sanitario (hospitalario, ambulatorio, UCIs, personal sanitario) y el tiempo de seguimiento medio. Se señaló el objetivo principal de cada estudio, así como la enumeración de las secuelas observadas. Se extrajo adicionalmente la sintomatología que aludía al dolor en exclusiva. Se expresó en porcentajes la prevalencia de dolor en distintas localizaciones de la anatomía humana, así como características del mismo.

Resultados

Se revisó por título y resumen un total de 678 artículos, obtenidos como resultado de la ecuación de búsqueda definida. A continuación, se seleccionaron 54 publicaciones por investigadores independientes, y se abordó su lectura a texto completo. Por falta de cumplimiento de criterios de inclusión, se excluyeron un total de 43. Los motivos de exclusión fueron: doce artículos trataban de síntomas crónicos pero no incluían el dolor, catorce eran reporte de un caso o de tamaños muestrales inferiores a 50, cuatro eran cartas al editor, nueve se centraban en síntomas agudos o no dolorosos, dos artículos no cumplían los criterios de la edad, uno por el idioma y otro por estudiar a población no COVID. Finalmente se seleccionaron un total de 11 estudios para su análisis.

La mayoría de los estudios identificados fueron publicados entre julio de 2020 y enero de 2021. Cuatro fueron estudios transversales, cinco fueron estudios de cohortes, tres retrospectivos y dos prospectivos, y una revisión sistemática. La revisión sistemática implicó estudios multicéntricos, mientras que, de los otros estudios, cuatro fueron realizados en EEUU (uno de ellos incluyó trece Estados norteamericanos), y los demás en Italia, España, Suiza, Francia y Egipto.

De forma mayoritaria, los estudios se llevaron a cabo mediante encuestas a pacientes recuperados de la infección aguda por el SARS-CoV-2, de forma ambulatoria y en ocasiones telefónica dadas las restricciones de los confinamientos domiciliarios durante la pandemia. De todos ellos, cinco publicaciones se centraron en pacientes que requirieron ingreso hospitalario; dos en pacientes que padecieron la fase aguda de la enfermedad en ámbito ambulatorio; y cuatro de ellos se desconoce si requirieron ingreso o no. Una media de 697 pacientes fue incluida en los estudios seleccionados. La edad media de los sujetos fue de 45 años sin diferencias en cuanto al sexo de los pacientes estudiados.

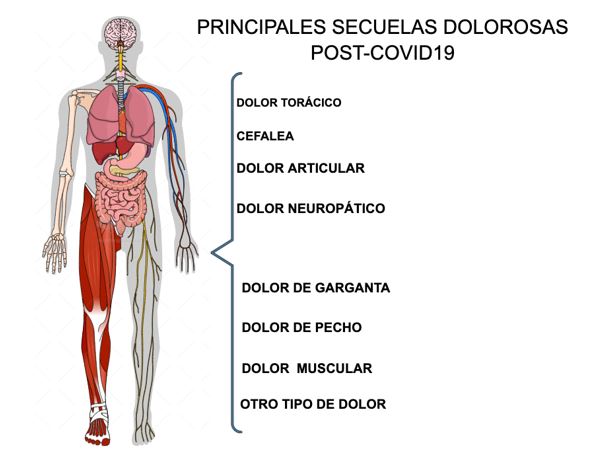

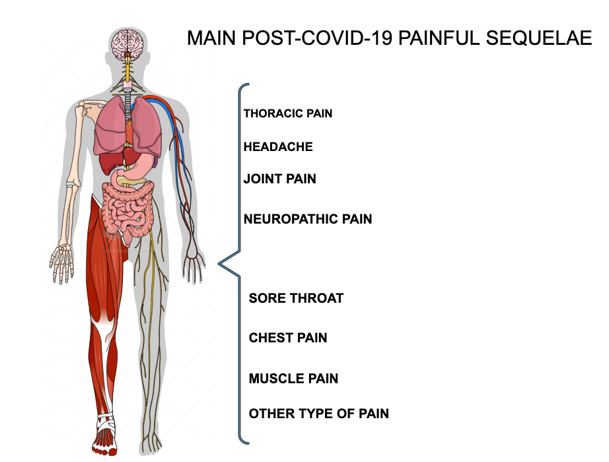

De todos los estudios incluidos, la cefalea es la secuela dolorosa más frecuentemente reportada, llegando a notificarse en una prevalencia de hasta el 44% tras la infección aguda según Sandra López-León et al. (4). Dos artículos reportaron resultados sobre dolor muscular (4, 18). El dolor articular como secuela tras dos semanas de la infección se notificó con un porcentaje de 19% y 31% (4, 23). El dolor torácico post COVID-19 se notificó en una horquilla porcentual entre 6% y 28% de los pacientes incluidos en sendos estudios (20, 23, 24, 25). El dolor de garganta persistente se reportó en el 32% de los pacientes; así como el dolor inespecífico o generalizado se observó en hasta un 59% de los casos, tal y como refiere el estudio de Tenforde et al. (25). El dolor neuropático secundario a la polineuropatía del paciente crítico fue relevante en pacientes que requirieron ingreso en UCI prolongado (15, 17). En la figura 1 se asocia un esquema visual de las diferentes secuelas dolorosas.

Figura 1: Secuelas dolorosas más frecuentes post-COVID-19

Por otra parte, se ha publicado que el SARS-CoV-2 ocasiona daños a nivel de la microcirculación capilar, generando hipoxia tisular e inflamación, con el consecuente aumento de las secuelas dolorosas de tipo vasculo-isquémico (6). Adicionalmente, se ha reportado que pasada la infección niveles altos de anticuerpos persistentes se asocian a fiebre, diarrea y otras secuelas (7).

Discusión

La pandemia por la COVID-19 supone una revolución para la sanidad tal como la conocemos hasta ahora. En primer lugar, por el cambio que ha provocado en la atención sanitaria. En segundo lugar, por la fisiopatología propia de la enfermedad, que aún es mayoritariamente desconocida. Y por último, por cómo está afectando y afectará a la salud de las personas (8).

La pandemia COVID-19 ha ocasionado el cese o la reducción de la actividad de multitud de servicios sanitarios. Ha provocado el retraso o la detención de tratamientos (9, 10), produciendo consecuencias negativas como aumento del dolor crónico, de la discapacidad o de la depresión en sus pacientes (13, 14, 39). La irrupción de la telemedicina como herramienta barrera para frenar los contagios del virus hace necesario más que nunca hacer partícipes a los pacientes de su salud. Los sanitarios deben estar muy atentos para proporcionar a los pacientes una adecuada educación sobre su patología de base y opciones de manejo de su dolor, así como implicarlos en procesos de decisión participativa. La telemedicina parece ser un recurso prometedor en el abordaje, tratamiento y seguimiento de los pacientes con dolor crónico (10, 17, 39).

Por otra parte, las secuelas dolorosas de la COVID-19 parecen responder a diferentes mecanismos etiopatogénicos. Se ha documentado desde de cefaleas en las formas leves de la enfermedad, hasta dolorosas neuropatías inflamatorias del paciente crítico (32). El dolor muscular es común tanto en las formas leves como en las severas (33). El espectro de dolor isquémico también ha emergido como complicación, asociado a la hipercoagulabilidad y a la disfunción en la microcirculación asociada (7). Todo ello se investiga en la actualidad para alcanzar una mayor comprensión de la enfermedad y los síntomas que a largo plazo puede provocar.

Por otro lado, el periodo de contagiosidad de los pacientes con prueba de detección de SARS-CoV-2 positiva es de veinte días aproximadamente (40). Una vez recuperados de la clínica aguda, se da el alta en los servicios hospitalarios en que hayan sido atendidos (21). La creación de unidades multidisciplinares para hacer seguimiento a los pacientes que fueron dados de alta tras ingreso por la COVID-19 es ya realidad en muchos centros. Sin embargo, multitud de pacientes con dolor post-COVID-19 que sufrieron una infección aguda paucisintomática, leve o moderada, que quedan excluidos de estas unidades porque fueron tratados y seguidos ambulatoriamente (4, 22, 25, 26, 27). Se hace hincapié en la calidad de la atención sanitaria para aquellos que, si bien están “recuperados” de la infección aguda y están fuera de peligro, siguen padeciendo síntomas que limitan su calidad de vida (28). En el presente estudio se ha tratado de arrojar luz y comprobar que el dolor crónico post-COVID-19 es una realidad que en ocasiones está infravalorada e infratratada. Por ello con los resultados del presente análisis y junto con apoyo en otros estudios, se sugiere la importancia de la creación de unidades multidisciplinares que atiendan a estos pacientes originalmente menos graves. Es crucial que tengan un seguimiento médico a largo plazo dirigido a detectar y tratar los síntomas derivados de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 (3, 4, 5, 11, 25, 36).

Consideramos de gran interés evaluar en futuros estudios la forma de abordar el dolor post-COVID-19 según localización, características y respuesta a los tratamientos realizados.

Limitaciones

La selección de artículos por revisores independientes fue una limitación encontrada durante la búsqueda bibliográfica en términos de precisión. Se amplió con literatura tomada de las referencias de artículos escogidos. Las grandes bases de datos consultadas aportaron artículos con poca relación con la COVID-19, frente a la nueva gran biblioteca LitCovid como base de datos centrada exclusivamente en SARS-CoV-2 (22). Además, la mayoría de los artículos seleccionados no tratan el dolor como única secuela de la COVID-19. Faltan aún estudios que aporten tamaños muestrales mayores, así como estudios prospectivos que traten las secuelas dolorosas en su dimensión temporal. Es preciso profundizar en las características, intensidad, localización y otras variables para mejor filiación del dolor como secuela de la COVID-19.

Conclusiones

La infección por COVID-19 para muchos de los pacientes no termina después de haberse recuperado de la infección aguda. En la actualidad no se conocen en profundidad los fenómenos Long-COVID, ni menos aún sus potenciales consecuencias. Hay ya numerosas líneas de investigación dirigidas a arrojar luz sobre la historia natural de una enfermedad que se está viviendo a tiempo real. La COVID-19 produce secuelas dolorosas de diversa índole. Ya hay indicios de que la incidencia de dolor crónico post-COVID-19 ha aumentado. Se requieren estudios posteriores para filiar las características de los distintos tipos de dolor. Se incide sobre la necesidad de hacer un adecuado uso de la telemedicina. Además, se hacen necesarias unidades multidisciplinares que reciban y estudien los casos de Long-COVID. Esto permitirá un manejo sintomatológico adecuado y una optimización de los recursos disponibles para hacer frente a los retos que la actual pandemia supone para las distintas áreas asistenciales.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Las autoras de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», especialmente a Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos-Bossini por su apoyo y tutorización, así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Las autoras de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

- Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Inf Dis. 20(5):533-534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1.

- Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli. Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-5.

- Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, et al. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv Prepr Serv Health Sci. 2021.

- Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res; 32(8):1613-20.

- Amjadi MF, O’Connell SE, Armbrust T, Mergaert AM, Narpala SR, Halfmann PJ, et al. Fever, Diarrhea, and Severe Disease Correlate with High Persistent Antibody Levels against SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. ;2021.01.05.21249240.

- Østergaard L. SARS CoV-2 related microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19: Consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Physiological Reports. 2021; 9(3):e14726.

- Walitt B, Bartrum E. A clinical primer for the expected and potential post-COVID-19 syndromes. PR9. 2021; 6(1):e887.

- Shanthanna H, Strand NH, Provenzano DA, Lobo CA, Eldabe S, Bhatia A, et al. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID ‐19 pandemic: consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75(7):935–44.

- Lynch ME, Williamson OD, Banfield JC. COVID-19 impact and response by Canadian pain clinics: A national survey of adult pain clinics. Canadian Journal of Pain. 2020; 4(1):204–9.

- Vittori A, Lerman J, Cascella M, Gomez-Morad AD, Marchetti G, Marinangeli F, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: Pain After the Storm? Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2020;131(1):117–9.

- Willi S, Lüthold R, Hunt A, Hänggi NV, Sejdiu D, Scaff C, et al. COVID-19 sequelae in adults aged less than 50 years: A systematic review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 40:101995.

- Hruschak V, Flowers KM, Azizoddin DR, Jamison RN, Edwards RR, Schreiber KL. Cross-sectional study of psychosocial and pain-related variables among patients with chronic pain during a time of social distancing imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Pain. 2021;162(2):619–29.

- Louw A. Letter to the editor: chronic pain tidal wave after COVID-19: are you ready? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2020; 36(12):1275–8.

- Orsucci D, Caldarazzo Ienco E, Nocita G, Napolitano A, Vista M. Neurological features of COVID-19 and their treatment: a review. DIC. 2020;9:1–12.

- Little P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and covid-19. BMJ. 2020; m1185.

- El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Pergolizzi JV, Gharibo C. Pain Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pain Ther. 2020;9(2):453–66.

- Jacobs LG, Gourna Paleoudis E, Lesky-Di Bari D, Nyirenda T, Friedman T, Gupta A, et al. Persistence of symptoms and quality of life at 35 days after hospitalization for COVID-19 infection. Madeddu G, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243882.

- Porta‐Etessam J, Matías‐Guiu JA, González‐García N, Gómez Iglesias P, Santos‐Bueso E, Arriola‐Villalobos P, et al. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2020;60(8):1697–704.

- Somani SS, Richter F, Fuster V, De Freitas JK, Naik N, Sigel K, et al. Characterization of Patients Who Return to Hospital Following Discharge from Hospitalization for COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2838-44.

- Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, Aebischer Perone S, Courvoisier D, Chappuis F, et al. COVID-19 Symptoms: Longitudinal Evolution and Persistence in Outpatient Settings. Ann Intern Med. 2020.

- PRISMA. Disponible en: http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram

- Kamal M, Abo Omirah M, Hussein A, Saeed H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;e13746.

- Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Le Bot A, Hamon A, Gouze H, et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e4-6.

- Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 31 de julio de 2020;69(30):993-8.

- Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, Torocastro M, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in «long COVID»: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(1):e63-7.

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Nagu P, Parashar A, Behl T, Mehta V. CNS implications of COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(2):219-34.

- Abboud H, Abboud FZ, Kharbouch H, Arkha Y, El Abbadi N, El Ouahabi A. COVID-19 and SARS-Cov-2 Infection: Pathophysiology and Clinical Effects on the Nervous System. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:49-53.

- Berger JR. COVID-19 and the nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020;26(2):143-8.

- Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos J-MS, Yan H, Lin S, Zabinski JS, Dinglas VD, et al. Fatigue Symptoms During the First Year Following ARDS. Chest. 2020;158(3):999-1007.

- Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a Cardinal Symptom of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache. 2020;60(10):2176-91.

- Sher L. Post-COVID syndrome and suicide risk. QJM. 2021.

- Barker-Davies RM, O’Sullivan O, Senaratne KPP, Baker P, Cranley M, Dharm-Datta S, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(16):949-59.

- Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z. LitCovid: an open database of COVID-19 literature. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020.

- Vidal-Alaball J, Acosta-Roja R, Pastor Hernández N, Sanchez Luque U, Morrison D, Narejos Pérez S, et al. Telemedicine in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aten Primaria. 2020;52(6):418-22.

- Xiao AT, Tong YX, Gao C, Zhu L, Zhang YJ, Zhang S. Dynamic profile of RT-PCR findings from 301 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104346.

Chronic Pain as a COVID-19 Sequela: A Systematic Review

Introduction

The persistence of COVID-19 sequelae is very common 14 days after acute infection. The term “long-COVID” has been proposed in order to refer to all the secondary conditions to SARS-CoV-2 infection which continue or appear after its acute stage. One of the sequelae is chronic pain with non-demonstrated organ involvement. This systematic review aims to identify the most commonly reported painful sequelae and their incidence.

Methods

A search for articles documenting pain as a consequence of COVID-19 was conducted. The consulted databases were PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science. Certain articles cited in the references of relevant articles were also incorporated. Depending on the detailed inclusion or exclusion criteria, three independent researchers carried out the selection. All the articles published before March 11th 2021 were included. This systematic review is based on the PRISMA guidelines.

Results

A total of 588 publications were identified, of which 11 met the inclusion criteria. Headache was the most frequently reported painful sequela, with a prevalence of up to 44% in some cases. Joint pain (19%-31%) and post-COVID thoracic pain (6%-28%) were notified. Persistent sore throat was reported in 32% of patients, as well as generalized pain, observed in up to 59% of the cases. Patient’s polyneuropathy that required admission to the internal care unit (ICU) was additionally notified. SARS-CoV-2 causes damage at the capillary microcirculation level, generating tissue hypoxia and inflammation, with the consequent increase in painful vascular-ischemic and inflammatory sequelae.

Conclusions

COVID-19 produces painful sequelae of various typologies. Subsequent studies are required in order to identify the characteristics of every different type of pain. This will allow an adequate symptomatologic management and an optimization of the available resources to face the challenges of the current pandemic in different healthcare areas.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, pain, painful sequelae, long-COVID, post-COVID, persistent COVID.

Introduction

Since the first COVID-19 case reported in Wuhan (1) on December 31st 2019, 116 million people (2) have been infected as of March 21st 2021. Many of them do not fully recover but suffer long-term unspecific chronic pain. These effects are not widely known yet (3). Cases of fatigue, headache, difficulty concentrating, hair loss and dyspnea (3, 12, 18) are reported with high frequency. For this reason, the term “long-COVID” has been suggested in order to bring together all the sequelae that arise two weeks after the disease has passed (4, 8).

It has been demonstrated that presence and severity of somatic symptoms during acute infection are closely related to the subsequent development of chronic fatigue and pain (11, 25). The daily clinical experience of the last few months in the Andalusian Health System (SAS, for its acronym in Spanish, Sistema Andaluz de Salud), has experienced an increase of the influx in healthcare centers of patients with persistent COVID-19 symptoms. These symptoms worsen the quality of life, are difficult to identify in the diagnosis and do not disappear easily with the usual treatments (5). The most common symptoms are myalgia, referred pain, and generalized hyperalgesia (17). They appear in different locations: head (20) and in thorax or limbs (15). Moreover, this disease responds to variable characteristics. Organicity has been ruled out, so the causal mechanism is unknown. However, it is being studied, and it is only associated with convalescence after COVID-19 (8).

It is unknown whether COVID-19 will cause an increase in new-onset chronic pain. The objective of this systematic review is to comprehensively compile reported data on pain as COVID-19 sequela. The secondary objective is to analyze whether the incidence of post-COVID chronic pain during the pandemic has increased. It is of interest to evaluate in future studies the patterns of post-COVID chronic pain, as well as its risk factors, intensity, characteristics, and response to currently used treatment.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was carried out by three independent researchers (VPF, PCP, and PJG). The consulted databases were PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. March 11th 2021 was the due date for article selection. In order to increase the sensitivity of the research, the bibliography cited in the articles finally selected was also reviewed. The followed strategy was based on the PRISMA guidelines (24). The search terms were “COVID-19”, “long*”, and “pain”, joined by the Boolean operator “AND”.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Publications available in English or Spanish were identified. Articles analyzing data from patients with pain symptoms more than two weeks after confirmed acute SARS-CoV-2 infection were selected. Non-ambulatory and ambulatory patients which required internal care unit (ICU) admission were included. Only data on the adult population were used. Prospective, retrospective and cross-sectional observational cohort studies were included, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The titles and abstracts of the articles found in the different databases after applying the search equation were systematically analyzed by independent researchers. Then, the articles which met the inclusion criteria were reviewed completely and jointly by three researchers. Finally, the inclusion or exclusion of the studies was discussed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Publications in languages other than English or Spanish, and whose study population included children (under 18 years of age) and pregnant women were excluded. Any symptomatology secondary to COVID-19 after at least two weeks following the acute stage was considered to be a persistent sequela. Studies with a sample size of less than 50 individuals were rejected.

Data extraction of the included articles

The references found on the systematic research were imported into the Zotero reference manager. After removing duplicate items, a single reference folder was created. The following information was chosen from the selected articles: number of subjects studied, country where data were collected, mean age, sex, healthcare setting (inpatient, outpatient, ICUs, healthcare staff) and mean follow-up time. The main objective of each study was pointed out, as well as the enumeration of the sequelae observed. Symptomatology related exclusively to pain was also extracted. The prevalence of pain in different locations of the body was expressed in percentages, and their characteristics were listed.

Results

A total of 678 articles, retrieved as a result of the defined search equation, were reviewed based on their title and abstract. Subsequently, 54 publications were selected by independent researchers, who fully read all of them. Of them, 43 were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. The specific reasons for exclusion were the following: 12 articles addressed chronic symptoms but did not include pain; 14 were single case reports or had sample sizes of less than 50; 4 were letters to the editor; 9 focused on acute or non-painful symptoms; 2 did not meet age criteria; 1 did not meet language criteria; and 1 studied non-COVID population. A total of 11 studies were finally selected for analysis.

Most of the studies identified were published between July 2020 and January 2021: 4 were transversal studies; 5 were cohort studies; 3 were retrospective; 2 were prospective; and 1 was a systematic review. The systematic review involved multi-center studies. In the case of the other studies, 4 were carried out in the USA (one of them included 13 North American states); the remaining ones in Italy, Spain, Switzerland, France, and Egypt.

Most of the studies were carried out by means of surveys of patients recovered from acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, on an outpatient basis and sometimes by phone due to the restrictions of home confinement during the pandemic. Of those publications, 5 focused on patients that required hospitalization, 2 on outpatients that experienced the acute phase of the disease, and 4 are not known to have required hospitalization. An average of 697 patients were included in the selected studies. The mean age of the subjects was 45 years, with no differences regarding the sex of the patients studied.

Of all the included studies, headache is the most frequently reported painful sequela, with a reported prevalence of up to 44% after acute infection according to Sandra López-León et al. (4). Two articles reported results on muscle pain (4, 18). Joint pain as a sequela after two weeks of infection was reported at 19% and 31% (4, 23). Post-COVID-19 thoracic pain was reported in a percentage range of 6% to 28% of patients included in the studies (20, 23, 24, 25). Persistent sore throat was reported in 32% of patients, and non-specific or generalized pain was observed in up to 59% of cases, according to the study by Tenforde et al. (25). Neuropathic pain secondary to polyneuropathy in critically ill patients was significant among patients that required a prolonged ICU admission (15, 17). Figure 1 shows a visual scheme of the different painful sequelae.

Figure 1. Most common post-COVID-19 painful sequelae

In addition, SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to cause damage to at the capillary microcirculation level, leading to tissue hypoxia and inflammation, and consequently to an increase in painful vascular-ischemic sequelae (6). It has also been reported that high levels of persistent antibodies after the infection are associated with fever, diarrhea and other sequelae (7).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a revolution for healthcare as we know it. Firstly, because of the change it has caused in clinical care. Secondly, because of the pathophysiology of the disease, which remains largely unknown. Lastly, because of how it is affecting and will affect people’s health (8).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led many health services to cease or reduce their activity. Treatments have been delayed or stopped (9, 10), resulting in negative effects such as increases in patients’ chronic pain, disability and depression (13, 14, 39). The emergence of telemedicine as a barrier tool to curb the spread of the virus makes more necessary than ever engaging patients in their own health. Healthcare professionals must pay close attention to properly educating patients on their underlying pathology and pain management options, while involving them in participatory decision-making processes. Telemedicine appears to be a promising resource in the management, treatment and follow-up of patients with chronic pain (10, 17, 39).

In addition, the painful sequelae of COVID-19 seem to respond to different etiopathogenic mechanisms. Reports range from headache, in mild forms of the disease, to painful inflammatory neuropathies in critically ill patients (32). Muscle pain is common in both mild and severe forms (33). The spectrum of ischemic pain has also emerged as a complication, linked to hypercoagulability and associated microcirculatory dysfunction (7). All of this is currently being researched in order to achieve a better understanding of the disease and the long-term symptoms it may cause.

Meanwhile, the contagiousness period for patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 screening test is approximately twenty days (40). Once recovered from the acute symptoms, they are discharged from the hospital services where they have been treated (21). Many centers have already set up multidisciplinary units to follow up discharged patients after admission for COVID-19. However, there is also a large number of patients with post-COVID-19 pain who suffered a mild or moderate paucisymptomatic acute infection, who are left out of these units because they were treated and followed up on an outpatient basis (4, 22, 25, 26, 27). Emphasis is placed on the quality of healthcare for those who, while “recovered” from the acute infection and out of danger, still suffer from symptoms that limit their quality of life (28). This study tried to shed light and prove that post-COVID-19 chronic pain is a reality which is sometimes underestimated and undertreated. For that reason, the results of this analysis, supported by other studies, suggest the importance of setting up multidisciplinary units to care for the patients whose original condition was less severe. It is crucial that they receive long-term medical follow-up, aimed at detecting and treating symptoms derived from SARS-CoV-2 infection (3, 4, 5, 11, 25, 36).

It is of great interest to evaluate in future studies the approach to post-COVID-19 pain according to location, characteristics and response to the treatments carried out.

Limitations

The selection of articles by independent reviewers constituted a limitation, in terms of accuracy, during the literature research. This was expanded with literature taken from the references of the articles selected. The large databases consulted provided articles with little relation to COVID-19, in contrast to the new large library LitCovid, a database focused exclusively on SARS-CoV-2 (22). In addition, most of the selected articles did not address pain as the only sequela of COVID-19. There is still a lack of studies that provide larger sample sizes, as well as prospective studies that address pain sequelae in their temporal dimension. The characteristics, intensity, localization and other variables need to be examined in more depth to better classify pain as a sequela of COVID-19.

Conclusions

For many patients, COVID-19 infection does not end after acute infection recovery. At present, long-COVID phenomena are not well understood, let alone their potential consequences. Several lines of research aimed at shedding light on the natural history of a disease that is being experienced in real time. COVID-19 has painful sequelae of various typologies. There is already evidence of an increase in the incidence of post-COVID-19 chronic pain. Further studies are required to identify the characteristics of the different types of pain. The need to make appropriate use of telemedicine is emphasized. Moreover, multidisciplinary units that receive and study long-COVID cases are needed. This will allow a proper symptomatologic management and an optimization of the available resources to face the challenges of the current pandemic in different healthcare areas.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, especially Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos-Bossini for his support and mentorship, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

- Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Inf Dis. 20(5):533-534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1.

- Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli. Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-5.

- Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, et al. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv Prepr Serv Health Sci. 2021.

- Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res; 32(8):1613-20.

- Amjadi MF, O’Connell SE, Armbrust T, Mergaert AM, Narpala SR, Halfmann PJ, et al. Fever, Diarrhea, and Severe Disease Correlate with High Persistent Antibody Levels against SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. ;2021.01.05.21249240.

- Østergaard L. SARS CoV-2 related microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19: Consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Physiological Reports. 2021; 9(3):e14726.

- Walitt B, Bartrum E. A clinical primer for the expected and potential post-COVID-19 syndromes. PR9. 2021; 6(1):e887.

- Shanthanna H, Strand NH, Provenzano DA, Lobo CA, Eldabe S, Bhatia A, et al. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID ‐19 pandemic: consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia. 2020; 75(7):935–44.

- Lynch ME, Williamson OD, Banfield JC. COVID-19 impact and response by Canadian pain clinics: A national survey of adult pain clinics. Canadian Journal of Pain. 2020; 4(1):204–9.

- Vittori A, Lerman J, Cascella M, Gomez-Morad AD, Marchetti G, Marinangeli F, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: Pain After the Storm? Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2020;131(1):117–9.

- Willi S, Lüthold R, Hunt A, Hänggi NV, Sejdiu D, Scaff C, et al. COVID-19 sequelae in adults aged less than 50 years: A systematic review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 40:101995.

- Hruschak V, Flowers KM, Azizoddin DR, Jamison RN, Edwards RR, Schreiber KL. Cross-sectional study of psychosocial and pain-related variables among patients with chronic pain during a time of social distancing imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Pain. 2021;162(2):619–29.

- Louw A. Letter to the editor: chronic pain tidal wave after COVID-19: are you ready? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2020; 36(12):1275–8.

- Orsucci D, Caldarazzo Ienco E, Nocita G, Napolitano A, Vista M. Neurological features of COVID-19 and their treatment: a review. DIC. 2020;9:1–12.

- Little P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and covid-19. BMJ. 2020; m1185.

- El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Pergolizzi JV, Gharibo C. Pain Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pain Ther. 2020;9(2):453–66.

- Jacobs LG, Gourna Paleoudis E, Lesky-Di Bari D, Nyirenda T, Friedman T, Gupta A, et al. Persistence of symptoms and quality of life at 35 days after hospitalization for COVID-19 infection. Madeddu G, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243882.

- Porta‐Etessam J, Matías‐Guiu JA, González‐García N, Gómez Iglesias P, Santos‐Bueso E, Arriola‐Villalobos P, et al. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2020;60(8):1697–704.

- Somani SS, Richter F, Fuster V, De Freitas JK, Naik N, Sigel K, et al. Characterization of Patients Who Return to Hospital Following Discharge from Hospitalization for COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2838-44.

- Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, Aebischer Perone S, Courvoisier D, Chappuis F, et al. COVID-19 Symptoms: Longitudinal Evolution and Persistence in Outpatient Settings. Ann Intern Med. 2020.

- PRISMA. Available at: http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram

- Kamal M, Abo Omirah M, Hussein A, Saeed H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;e13746.

- Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Le Bot A, Hamon A, Gouze H, et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e4-6.

- Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 31 de julio de 2020;69(30):993-8.

- Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, Torocastro M, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in «long COVID»: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(1):e63-7.

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Nagu P, Parashar A, Behl T, Mehta V. CNS implications of COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(2):219-34.

- Abboud H, Abboud FZ, Kharbouch H, Arkha Y, El Abbadi N, El Ouahabi A. COVID-19 and SARS-Cov-2 Infection: Pathophysiology and Clinical Effects on the Nervous System. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:49-53.

- Berger JR. COVID-19 and the nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020;26(2):143-8.

- Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos J-MS, Yan H, Lin S, Zabinski JS, Dinglas VD, et al. Fatigue Symptoms During the First Year Following ARDS. Chest. 2020;158(3):999-1007.

- Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a Cardinal Symptom of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache. 2020;60(10):2176-91.

- Sher L. Post-COVID syndrome and suicide risk. QJM. 2021.

- Barker-Davies RM, O’Sullivan O, Senaratne KPP, Baker P, Cranley M, Dharm-Datta S, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(16):949-59.

- Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z. LitCovid: an open database of COVID-19 literature. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020.

- Vidal-Alaball J, Acosta-Roja R, Pastor Hernández N, Sanchez Luque U, Morrison D, Narejos Pérez S, et al. Telemedicine in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aten Primaria. 2020;52(6):418-22.

- Xiao AT, Tong YX, Gao C, Zhu L, Zhang YJ, Zhang S. Dynamic profile of RT-PCR findings from 301 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104346.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: De Pablos-Florido V, Córdoba-Peláez P, Jiménez-Gutiérrez P. M. Dolor persistente como secuela de la COVID-19: una revisión sistemática. AMU. 2021; 3(1):80-91