Cristina Morato-Gabao ¹ , David Navares-López ² , Rosa Pérez-Martínez ² , Laura Romero-de-los-Reyes ² , Lucía Solier- López ²

1 Estudiante del Programa de Doctorado en Psicología de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

2 Estudiante del Máster en Neurociencias Básicas Aplicadas y Dolor de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

TRANSLATED BY:

Marina Fernández-Basallo ³ , Alicia Gómez-Patiño ³ , Julia González-Cuenca ³ , María Repiso-Núñez ³ , María Pineda- Cantos ³ , Javier Saldaña-Martínez ³

3 Student of the BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (UGR)

Resumen

En los últimos años, el dolor neuropático localizado ha alcanzado una prevalencia superior al 50% en pacientes atendidos en clínicas de dolor. Además, un 20% del dolor crónico que presentan los pacientes es neuropático. Esto hace necesarios una definición, diagnóstico e intervención apropiados para hacer frente a esta afección y mejorar la calidad de vida de estos pacientes. Este artículo tiene como objetivo realizar una revisión de la bibliografía existente en los últimos años sobre esta afección, así como llevar a cabo una aproximación al dolor neuropático localizado, centrada en la fisiopatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento, tanto farmacológico -entre las que destacan lidocaína y capsaicina en formulación tópica- como no farmacológico. Por último, se realiza una discusión y se plantean unas perspectivas futuras sobre el estudio del

dolor neuropático localizado.

Palabras clave: dolor neuropático localizado, dolor crónico, capsaicina, lidocaína.

Keywords: localized neuropathic pain, chronic pain, capsaicin, lidocaine.

- Introducción

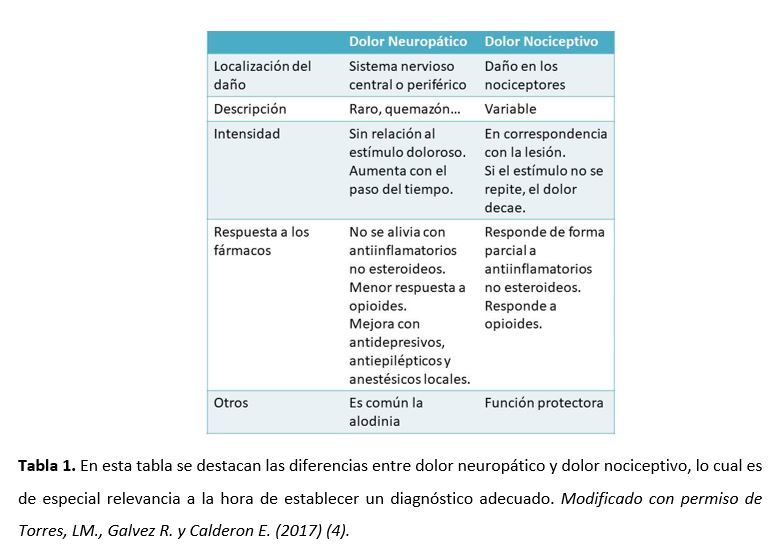

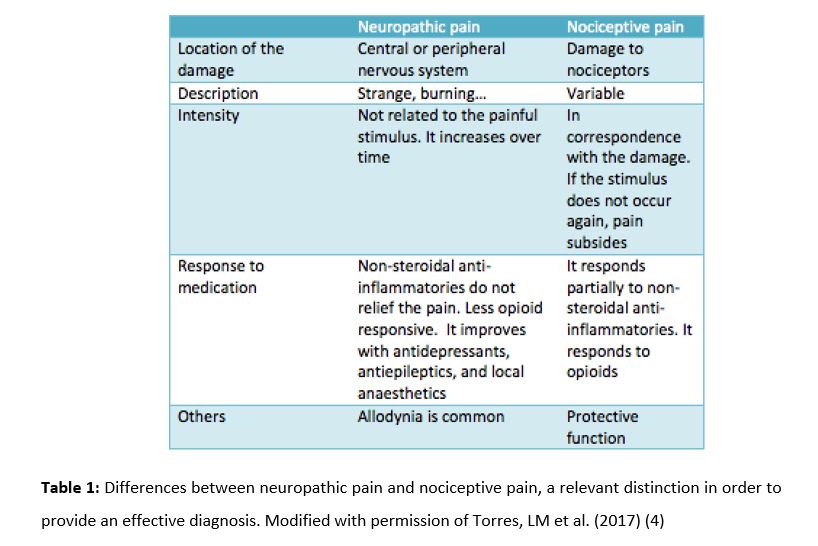

Según la Asociación Internacional para el Estudio del Dolor (IASP) el dolor es una experiencia sensorial y emocional desagradable asociada con un daño real o potencial en un tejido, o descrito en términos de dicho daño (1) y sirve como función de alerta para el organismo. Por su parte el dolor neuropático (DN) es un tipo específico de dolor que es definido como un dolor causado por una lesión o enfermedad del sistema nervioso somatosensorial (2). Éste puede ser de origen central (por daño en la médula o en el cerebro) o periférico (por daño en nervios periféricos) así como localizado (si afecta un área circunscrita del cuerpo) o difuso. Contar con una buena definición de cada tipo de dolor es fundamental para poder mejorar la clasificación de los pacientes y así poder ajustar el tratamiento de la forma más específica posible (3). En la Tabla 1, podemos ver las diferencias entre DN y dolor nociceptivo (4).

En el 2010 un grupo de expertos en dolor se reunieron para crear una primera definición del dolor neuropático localizado (DNL) definiéndolo como un tipo de dolor neuropático que se caracteriza por una o más áreas consistente y circunscrita de dolor máximo (5). Sin embargo, hace falta una definición más completa que ayude a ajustar mejor los tratamientos existentes a cada tipo de paciente según el tipo de dolor que presente y su localización (3).

La incidencia del DN se ha estimado entre el 6,9 y el 10% de la población (6). Sin embargo, faltan estudios que especifiquen la prevalencia de cada tipo de dolor neuropático. Es importante resaltar que el 20% de dolor crónico es neuropático (7), por lo que diagnosticarlo y tratarlo adecuadamente es necesario para la mejora en la calidad de vida de estos pacientes. Según la Guía para el abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico farmacológico del dolor neuropático periférico localizado (4), un estudio realizado con pacientes atendidos en clínicas de dolor mostró una incidencia del 51,9% siendo en su mayoría mujeres y con mayor prevalencia del DN periférico, un dato mayor que en otros países de Europa. Según una encuesta realizada a médicos la prevalencia del DNL en sus pacientes con DN fue del 60% en una muestra de 869 personas (5).

Diversos estudios coinciden en el uso principalmente de lidocaína al 5% (8)(9), la capsaicina (10)(11), clonidina y la toxina botulínica del tipo A (BTX-A) para el tratamiento tópico (12)(13).

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo realizar una revisión de la literatura sobre el dolor neuropático localizado y profundizar en los apartados de fisiopatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento de esta afección.

- Fisiopatología

El DN es causado por una lesión o enfermedad que afecta al sistema somatosensorial (12). La lesión o inflamación de tejidos periféricos induce cambios adaptativos reversibles en el sistema nervioso que provocan dolor por sensibilización, actuando como un mecanismo protector para asegurar la cura adecuada de los tejidos. En el DN estos cambios en la sensibilización van a ser persistentes, produciendo clínicamente dolor espontáneo, con bajo umbral del estímulo e incluso inicio o incremento del dolor con estímulos no dolorosos. Esto produce cambios maladaptativos de las neuronas sensitivas pudiendo ser irreversibles (7) (14).

Entre los cambios fisiológicos que se producen en la periferia está la hiperexcitabilidad eléctrica, la generación de impulsos anormales (electrogénesis ectópica) (15) en el axón y en neuronas del ganglio dorsal (7) que se desarrolla en las neuronas sensitivas primarias lesionadas. La ectopia implica el disparo espontáneo en algunas neuronas, y la respuesta anormal a los estímulos mecánicos, térmicos y químicos en muchas otras. La remodelación de los canales iónicos sensibles al voltaje, las moléculas y los receptores de transducción en la membrana celular parecen ser el mecanismo celular que subyace a la hiperexcitabilidad ectópica (15). Los canales específicos de Na+ y K+ parecen ser los principales responsables pues están más directamente implicados en el proceso de disparo repetido. Los canales de Na+ se acumulan en la membrana de los lugares de lesión del nervio y de desmielinización, la síntesis de los subtipos está aumentada, y su contribución individual se puede ver aumentada por los mediadores de la hiperalgesia. También se produce regulación a la baja y el bloqueo de los canales de K+. La descarga ectópica contribuye al DN constituyendo una señal aferente directa, así como pudiendo disparar y mantener la sensibilización central (15). Así mismo, se produce sensibilización de los nociceptores, presencia de efapses e interacción anormal entre fibras. A nivel central se produce sensibilización de las neuronas del asta posterior y alteración de los mecanismos inhibitorios descendentes (7).

El DNL también se caracteriza por hiperexcitabilidad periférica, con sobreexpresión de sodio y canales de la familia 1 de TRPV localizados en las membranas de células nerviosas. La acción analgésica de fármacos tópicos usados para el tratamiento de DN, está relacionada específicamente con dichos canales, ampliamente distribuidos en la superficie de las fibras nociceptivas superficiales/epidérmicas (16).

El Síndrome de DN suele presentarse como una combinación compleja de síntomas con variación interindividual que depende de los cambios fisiopatológicos subyacentes, resultantes de la convergencia de múltiples factores etiológicos, genotípicos y del medioambiente (7).

- Manifestaciones clínicas del DNL

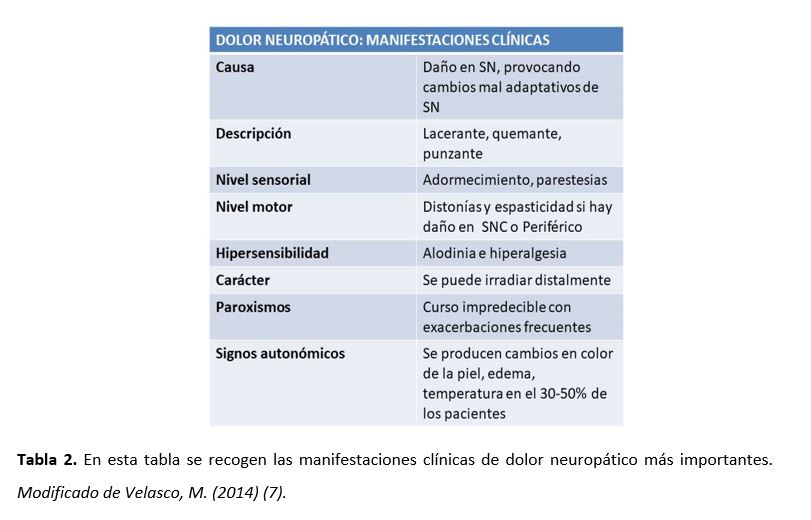

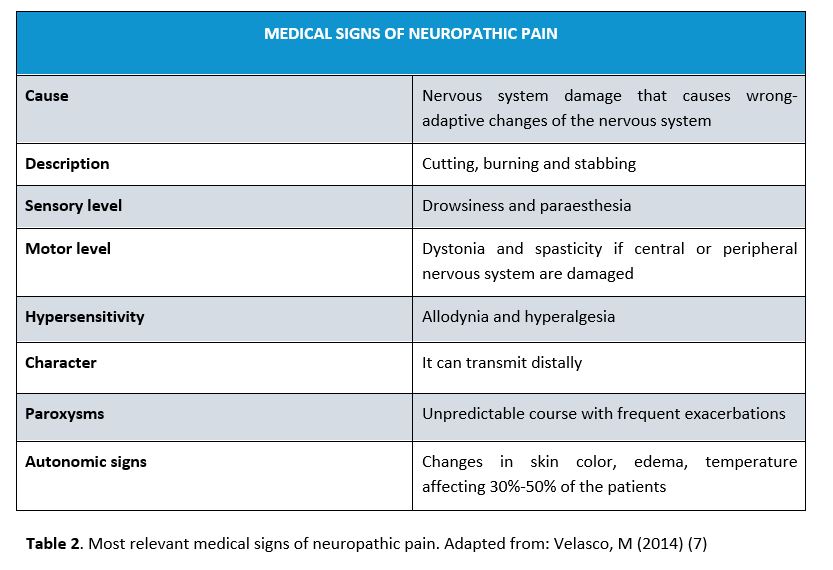

Los síntomas que se presentan en el DN pueden ser negativos (pérdida sensorial) o positivos (respuestas neurosensoriales anormales). Se pueden acompañar de problemas de somatización y de sueño, así como de alteraciones psicológicas (ansiedad y depresión entre otras). Los síntomas negativos son los primeros en determinar que hay daño en el sistema somatosensorial. Los positivos pueden ser tanto espontáneos (dolor espontáneo, disestesias, parestesias) como evocados (alodinia, hiperalgesia, hiperpatía) (7). En la tabla 2 quedan recogidas las manifestaciones clínicas más importantes (7).

- Diagnóstico

El diagnóstico de DN y DNL utiliza los mismos métodos, por lo que nos referiremos a ambos indistintamente. Según autores como Finnerup, Haroutounian y cols. (17) y la IASP (1) la evaluación de un paciente con dolor, que sugiere que podría ser por lesión o enfermedad neurológica y no por lesión en el tejido, debe realizarse con el siguiente sistema de clasificación: posible, probable o definitivo.

- Dolor Neuropático Posible

En primer lugar, es necesario evaluar si el historial nos dirige hacia una enfermedad o lesión neurológica. En este historial clínico se deben determinar antecedentes de dolor, enfermedades sufridas y comorbilidades existentes. Se puede emplear una escala EVA o escala numérica para determinar el grado de dolor del paciente (18). También existen escalas y cuestionarios para ello (17)(19). Podemos usar métodos electrofisiológicos: como la EMG o la conducción nerviosa o los test para evaluar fibras finas (7). Es recomendable realizar un examen físico, con el objetivo de localizar el área dolorosa (18). Se deben cumplir dos criterios para diagnosticar DNL posible. En primer lugar, se ha de observar si existe un correlato de algún problema neurológico importante a tener en cuenta (por ejemplo: ictus o una neuropatía diabética, entre otras). En segundo lugar, se ha de determinar la localización anatómica, para decidir si es compatible con la localización de la lesión en el sistema nervioso somatosensorial central o periférico (17). La aparición del dolor puede ser de forma inmediata o insidiosa, según el tipo de enfermedad o lesión que se haya producido. La relación temporal resulta relevante de cara al diagnóstico (17).

- Criterios para Dolor Neuropático Probable:

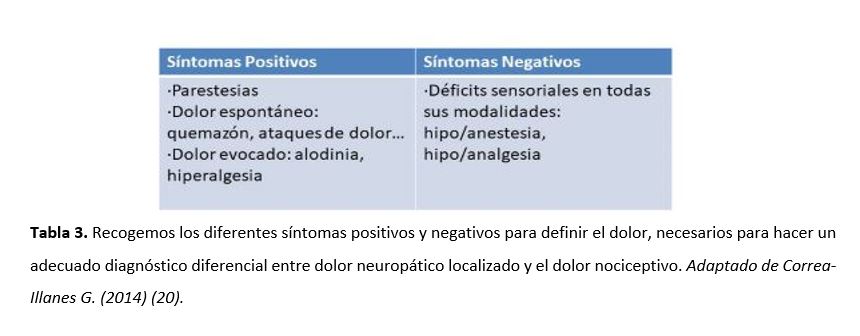

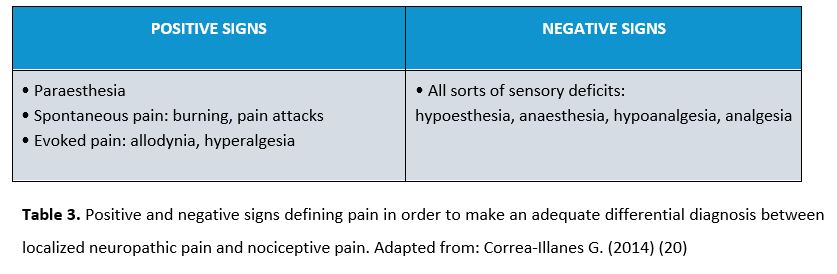

En este caso, se necesita apoyo clínico suficiente para corroborar lo encontrado previamente. A pesar de que pueden existir síntomas positivos, los síntomas negativos son los que van a dirigir al diagnóstico de DNL (17). En la tabla 3 quedan definidos los síntomas positivos y negativos del DN.

Para determinar la presencia de DNL probable deben resultar positivas las siguientes escalas y cuestionarios: LANSS, cuestionario de dolor neuropático, Douleur Neurophatique en 4 preguntas, painDETECT o el ID-Pain (17). Actualmente se ha desarrollado la Diagnostic Tool, herramienta específica para DNL, que nos ayuda a determinar el carácter localizado del DN (4) y que también debe dar positivo para determinar que es probable.

- Criterios para Dolor Neuropático Definitivo

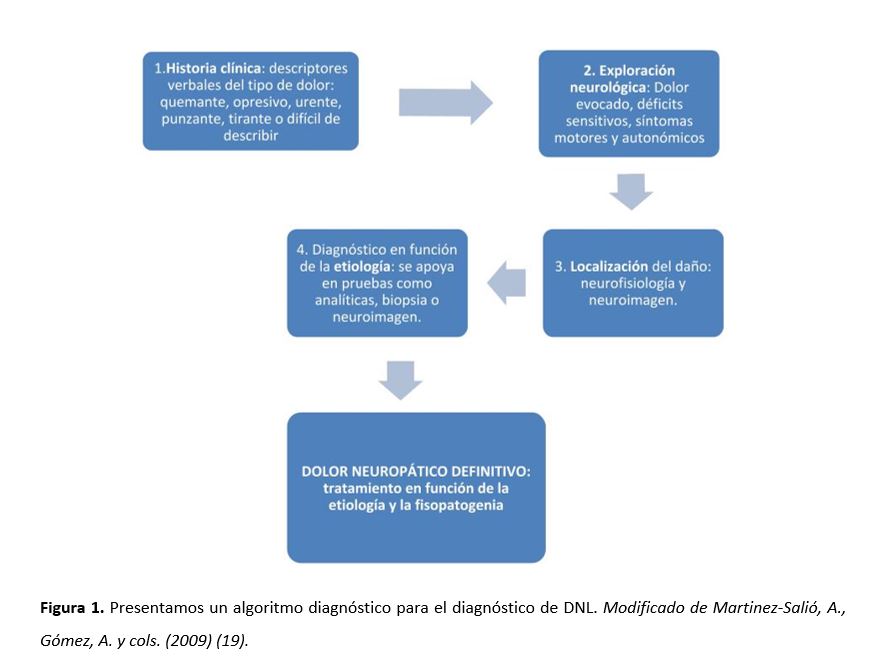

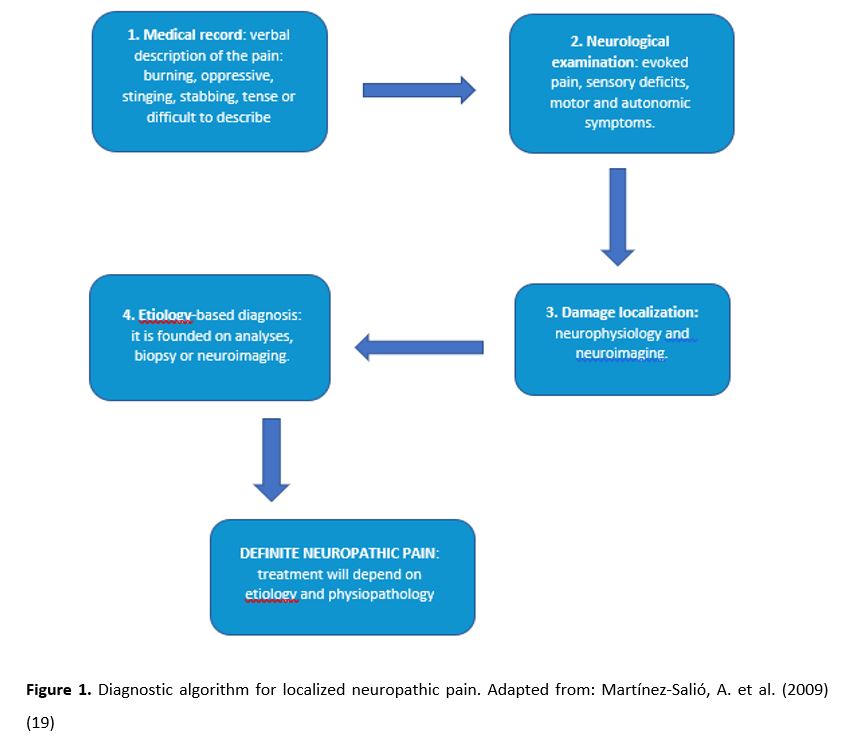

El diagnóstico debe sustentarse en pruebas de imagen que definan la lesión del sistema nervioso somatosensorial como resonancia magnética (RM), tomografía axial computerizada (TAC) (17), pruebas neurofisiológicas (electromiografía, conducción nerviosa, etc.) (4), potenciales evocados, test sensoriales cuantitativos, reflejos nociceptivos, entre otros (19). Cabe destacar que, aunque se cumplan estos indicadores, es posible que existan otras causas para el dolor, no estando seguros los expertos de que exista una causalidad directa (17). La Figura 1 representa un algoritmo diagnóstico en el que se enumeran los pasos a seguir ante la sospecha de DN.

- Tratamiento

- Tratamiento farmacológico

El tratamiento farmacológico de las enfermedades crónicas tiene como inconveniente la baja adherencia a largo plazo por parte de los pacientes. Además, la eficacia del tratamiento farmacológico del DN es limitada, observándose que solo el 40% de los pacientes resaltan un alivio significativo (16). Para el DNL se administran tratamientos tópicos, en su mayoría lidocaína al 5% y capsaicina al 8% (3).

- Lidocaína al 5%

Los parches de lidocaína al 5% son tratamiento de primera línea. Presentan una acción farmacológica a través de la lidocaína y una acción protectora debido al parche, actuando como una barrera mecánica frente a los estímulos que producen hiperalgesia (21). La lidocaína actúa mediante el bloqueo no selectivo de los canales de Na+ uniéndose a los poros de las pequeñas fibras locales dañadas. Este bloqueo produce el cese de la propagación de la señal. Al no ser un bloqueo sensorial completo de los canales de Na+ (21), la acción final dependerá de la afinidad y la tasa de unión del fármaco. El parche con lidocaína reduce la alodinia y los síntomas del dolor neuropático (3).

La lidocaína tiene una vida media en el paciente de 7,6 horas, siendo necesaria su administración cada 24 horas para mantener el efecto analgésico (16). Sus efectos adversos más comunes son eritemas, ardor, erupción cutánea, edema o dermatitis y están limitados a la zona del área de aplicación (16).

- Capsaicina al 8%

Cuando la neuropatía tiene su origen en neuralgia postherpética (PHN) o el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH), los parches de capsaicina están calificados como nivel A por la Federación Europea de Sociedades Neurológicas (16). La capsaicina interactúa con las fibras sensoriales aferentes mediante la afinidad agonista selectiva para el TRPV1, localizado principalmente en fibras Aδ, fibras C y en orgánulos intracelulares (16). La acción de la capsaicina está mediada por la apertura del canal TRPV1, al cual le siguen unos acontecimientos en cadena, la despolarización a través de Na+ y Ca2+ y la liberación de Ca2+ al retículo endoplasmático (22). La concentración alta de Ca2+ bloquea selectivamente los nervios sensoriales aferentes. La mejora de los síntomas del dolor nociceptivo ocurre entre 6 y 12 semanas con el uso de un solo parche de capsaicina al 8% (23). El efecto del fármaco puede durar 90 días, por lo que se administra cada 3 meses (16).

- Otros tratamientos tópicos y no tópicos

Existen tratamientos tópicos para el DNL que todavía no se han comercializado, como la ketamina, un agonista de receptores NMDA que actúa reduciendo el umbral de la transducción nerviosa y la sensibilización central (16). Aunque existen evidencias de su eficacia, no está aprobado para el tratamiento del DNL (3).

El dextrometorfano es otro antagonista no competitivo del receptor NMDA comercializado en forma de parche externo que actúa aliviando diferentes tipos de dolor, tanto musculares como reumáticos (16). La bupivacaína es un anestésico local que bloquea los canales de Na+, se comercializa en forma de parche y tiene una acción prolongada, proporcionando un efecto de anestesia por un período de hasta 3 días después de una sola aplicación. Su efecto se compara con los parches de lidocaína al 5% (24). El diclofenaco y ketoprofeno son AINES (fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroides), disponibles como parches y cremas para tratar el dolor crónico (24). El uso de opioides agonistas μ fentanilo y la buprenorfina parcial agonista μ no ha sido probado en DNL, aunque se ha demostrado su eficacia en cáncer crónico y dolor no canceroso (3).

Los antidepresivos y antiepilépticos por vía oral también se recomiendan para el tratamiento del dolor neuropático localizado. Aunque existen numerosos fármacos antidepresivos y antiepilépticos, solo la rotigotina y la amitriptilina se han evaluado como tratamiento en dolor. Los antiepilépticos más utilizados en DNL son la gabapentina y la pregabalina administradas por vía oral (24).

En conclusión, el parche de lidocaína al 5% y el parche de capsaicina al 8% son los únicos apósitos tópicos que son específicos para tratar el DNL en la actualidad (16).

- Tratamiento no farmacológico

Existe, a día de hoy, escasa evidencia sobre el uso del tratamiento no farmacológico en el DNL. Sin embargo, los pocos datos existentes recomiendan su uso para tratar de disminuir el uso de medicamentos y mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes (25).

- Terapias intervencionistas:

La estimulación de la médula espinal es una estimulación eléctrica de baja intensidad de las fibras grandes de Aβ mielinizadas que modula las señales de dolor transmitidas por las fibras C no mielinizadas (26). Es la estrategia de neuromodulación más utilizada y mejor estudiada. Consiste en la aplicación de un pulso monofásico de onda cuadrada, que produce parestesia en la región afectada. Los nuevos tipos de estimulación, (ráfaga y estimulación de alta frecuencia), logran una estimulación sin parestesia y un alivio del dolor equivalente con el monofásico pulso de onda cuadrada. Estas técnicas tienen una seguridad relativa y resultan eficaces a largo plazo, según parecen demostrar los ensayos controlados aleatorios y varias series de casos (26).

La intervención en el ganglio de la raíz dorsal, nervio periférico y estimulación del campo del nervio periférico consisten en la neuroestimulación de las fibras aferentes fuera de la médula espinal y la estimulación subcutánea de la zona del nervio periférico. Un estudio de cohorte informó que la estimulación proporcionó una reducción de alrededor del 50% dolor (26).

La estimulación de la corteza motora epidural (ECMS), la estimulación magnética transcraneal repetitiva (rTMS) y la estimulación de corriente continua transcraneal (tDCS) de la corteza motora central por debajo del umbral motor (27) pueden reducir la hiperactividad del tálamo o activar vías inhibitorias descendentes. Los datos parecen indicar que aproximadamente un 60% de los pacientes responden a EMCS (28).

En la estimulación cerebral profunda se han sugerido como zonas objetivo la cápsula interna, núcleos en el tálamo sensorial, la sustancia gris periacueductal, la corteza motora, el septum, el accumbens, el hipotálamo posterior y la corteza cingulada anterior. La evidencia actual sobre esta técnica muestra riesgos significativos, siendo controvertida su aplicación (26).

- Terapias físicas:

Aunque existe escasa evidencia de la efectividad de la terapia física, hay indicios de que el ejercicio y las técnicas de representación de movimientos (como la terapia de espejo y las imágenes motoras que utilizan la observación o la imaginación de movimientos normales sin dolor) son beneficiosos (29).

- Terapias psicológicas:

Su objetivo es promover el manejo del dolor y reducir sus consecuencias emocionales. La terapia cognitivo-conductual es la más estudiada. Su propósito, como el de las demás terapias psicológicas, es dirigir al individuo a un ‘cambio individual’. Aborda el estado de ánimo, la función (incluyendo la discapacidad), el compromiso social y la analgesia de manera indirecta. A día de hoy, hay una baja evidencia de la efectividad de estas terapias en el DNL, requiriéndose más investigación al respecto (30).

- Discusión y perspectivas futuras

Actualmente, nos encontramos con múltiples desafíos con respecto al DNL. Existen dificultades para diagnosticar de forma adecuada a estos pacientes, siendo el primer problema la falta de consenso sobre la definición del término. A pesar de que se están llevando a cabo diversos debates entre expertos (5)(16), aún no existe un consenso global sobre la definición, lo que hace complejo un diagnóstico adecuado. Otro de los problemas es que no se conoce con exactitud a qué tratamientos específicos podrían responder los distintos tipos de dolor neuropático (3). Esto implica la existencia de pacientes con un tratamiento que no se ajusta a su patología de manera eficaz. Llevar a cabo nuevos estudios que aclaren las características fisiopatológicas del DNL nos orientaría a la hora de desarrollar nuevos tratamientos eficaces y específicos a este tipo de dolencia.

A modo de conclusión, existe una necesidad de ampliar el conocimiento que tenemos sobre el DNL, requiriéndose, en primer lugar, un consenso bien establecido sobre el término; en segundo lugar, llevar a cabo un mayor número de estudios acerca de la fisiología de esta patología; y en tercer lugar, de los tratamientos eficaces para cada tipo de dolor neuropático. Este avance implicaría una mayor adecuación de los tratamientos, incrementando su efectividad y suponiendo una mejora en la calidad de vida de los pacientes dada la cronicidad de esta patología.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés en este artículo.

Referencias

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition, IASP Press, Seattle, 1994. http://www.iasp-pain.org.

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008; 70(18): 1630-1635. Doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59

- Rey R. Tratamiento del dolor neuropático. Revisión de las últimas guías y recomendaciones. Neurolarg. 2013; 5(S1): S1–S7. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuarg.2011.11.004

- Torres LM, Galvez R, Calderon E. Guía para el abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico farmacológico del Dolor Neuropático Periférico Localizado (DNL). España: Asociación Andaluza del Dolor;

- Mick G, Baron R, Finnerup NB, et al. What is localized neuropathic pain? A first proposal to characterize and define a widely used term. Pain Manag. 2012; 2(1): 71-77. Doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.77

- Cruccu G, Truini A. A review of Neuropathic Pain: From Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Pain Ther. 2017; 6(1): 35-42. Doi: 1. 10.1007/s40122-017-0087-0

- Velasco M. Dolor neuropático. Med. Clin. Condes. 2014; 25(4): 625-634. Doi: 10.1016/S0716-8640(14)70083-5

- Amato F, Duse G, Consoletti L, et al. Efficacy and safety of 5% lidocaine-medicated plasters in localized pain with neuropathic and/or inflammatory characteristics: An observational, real-world study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017; 21(18): 4228-4235. https://www.europeanreview.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/4228-4235-5-lidocaine-medicated-plasters-in-localized-pain.pdf

- Baron R, Allegri M, Correa-Illanes G, et al. The 5% lidocaine-medicated plaster: its inclusion in international treatment guidelines for treating localized neuropathic pain, and clinical evidence supporting its use. Pain The 2016; 5(2): 149-169. Doi: 10.1007/s40122-016-0060-3

- Bhaskar A, Mittal R. Local therapies for localised neuropathic Pain. Rev pain. 2011; 5(2): 12-20. Doi:1177/204946371100500203

- Üçeyler N, Sommer C. High-dose capsaicin for the treatment of neuropathic pain: what we know and what we need to know. Pain Ther. 2014; 3(2): 73-84. Doi:1007/s40122-014-0027-1

- Allegri M, Baron R, Hans G, et al. A pharmacological treatment algorithm for localized neuropathic pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016; 32(2): 377-384. Doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2016.10.004

- Zur E. Topical treatment of neuropathic pain using compounded medications. Clin J Pain. 2014; 30(1): 73-91. Doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318285d1ba

- Kuner R, Flor H. Structural plasticity and reorganisation in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017; 18: 20-30. Doi: 1038/nrn.2016.162

- Devor M. Respuesta de los nervios a la lesión en relación con el dolor neuropático. En: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editores. Wall y Melzack Tratado del dolor. 5ª Ed. Madrid: Elsevier; 2007. 927-951

- Pickering G, Martin E, Tiberghien FL, Delorme CL, Mick G. Localized pain: an expert consensus on local treatments. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017; 11: 2709–2718. Doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S142630

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DL, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Freeman R, Hansson P, Nurmikko T, Raja SN, Rice AS, Serra J, Smith BH, Treede RD, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016; 157(8): 1599-606. Doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000492

- Fernández R, Ahumada, M et al. Guía para definición y manejo del dolor neuropático localizado: Consenso Chileno. El Dolor. 2011; 55: 12-31. https://www.ached.cl/upfiles/revistas/documentos/4fe37b78dcb16_dnl_55.pdf

- Martínez-Salió A, Gómez A, Ribera MV, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento del dolor neuropático. Med Clin. 2009; 133(16): 629–636. Doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2009.05.029

- Correa-Illanes G. Dolor Neuropático, clasificación y estrategias de manejo para médicos generales. Revista clínica médica las condes. 2014; 25(2): 189-199

- Sheets MF, Hanck DA. Molecular action of lidocaine on the voltage sensors of sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2003; 121(2): 163–175. Doi: 1085/jgp.20028651

- Derry S, Lloyd R, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Topical capsaicin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (4): CD007393. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub2

- Sawynok J. Topical analgesics for neuropathic pain: preclinical exploration, clinical validation, future development. Eur J Pain. 2014; 18(4): 465–481. Doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00400.x

- Lodge D. The history of the pharmacology and cloning of ionotropic glutamate receptors and the development of idiosyncratic nomenclature. Neuropharmacology. 2009; 56(1): 6–21. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.006

- Zilliox LA. Neuropathic pain. Continuum Minneap Minn. 2017; 23(2): 512–532. Doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000462

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017; 3: 1-19. Doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2

- Sukul VV., Slavin KV. Deep brain and motor cortex stimulation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014; 18(7): 1-5. Doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0427-2

- Lefaucheur JP. Cortical neurostimulation for neuropathic pain: state of the art and perspectives. Pain. 2016; 157: S81–S89. Doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000401

- Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 2: CD010152. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010152.pub2

- Dobson JL, McMillan J, Li L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014; 8: 1-9. Doi:3389/fncel.2014.00102

Localized Neuropathic Pain: A Narrative Review

Abstract

In the last few years, localized neuropathic pain has reached a prevalence rate of over 50% in patients who have attended pain clinics. Moreover, 20% of the chronic pain that patients suffer is neuropathic. Therefore, it is necessary to provide an adequate definition, diagnosis, and intervention in order to deal with this syndrome and improve patients’ quality of life. The aim of this article is to carry out a review of the existing literature on this syndrome that has been published in recent years. Moreover, a complementary objective of this article is to create an approach to localized neuropathic pain by focusing on its pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment, which can be pharmacological (e.g. lidocaine and capsaicin in topical formulation) or non-pharmacological. In the end, there is a final section with a discussion and some future perspectives about the study of localized neuropathic pain.

Keywords: localized neuropathic pain, chronic pain, capsaicin, lidocaine.

- Introduction

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is ”an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (1). Its purpose is to warn the organism. Meanwhile, neuropathic pain (NP) is a specific type of pain (syndrome) which is defined as “pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system” (2). It can have a central origin (caused by spinal cord or brain damage) or a peripheral origin (caused by peripheral nerve damage), and it can be localized (if it affects a specific area of the body) or diffuse. It is essential to have a clear definition of every different pain syndrome to improve the classification of the patients, so that treatments can be adapted as specifically as possible (3). Table 1 shows the differences between NP and nociceptive pain.

A group of pain experts met in 2010 to create the first definition of localized neuropathic pain (LNP). They defined it as “a type of neuropathic pain that is characterized by consistent and circumscribed area(s) of maximum pain” (5). However, a more comprehensive definition is required to help to adapt better existing treatments to each patient, depending on the type of pain that they suffer and its location (3).

NP incidence was estimated between 6.9%-10% of the population (6). However, there is a lack of studies specifying the prevalence of each type of NP. It is important to highlight that 20% of chronic pain is neuropathic (7). Therefore, it is essential to diagnose and treat it properly in order to improve patients’ quality of life. According to the Guide for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Pharmacological Approach of Localized Peripheral Neuropathic Pain (4), a study carried out with patients treated in pain clinics showed an incidence of 51.9%. The majority were women and had a greater prevalence of peripheral NP, considerably higher than in other European countries. As reported by a survey conducted among doctors, the prevalence of LNP in their patients suffering NP was 60% on a sample of 869 people (5).

Several studies agree on the primary use of 5% lidocaine (8, 9), capsaicin (10, 11), clonidine, and botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) for topical treatment (12, 13).

The purpose of this article is to carry out a review of the existing literature on LNP and to explore the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of this syndrome.

- Pathophysiology

NP is caused by a lesion or a disease which affects the somatosensory system (12). Such lesion or inflammation of peripheral tissues induces reversible adaptive changes in the nervous system that produce pain due to sensitization. This process acts as a protective mechanism to ensure the adequate healing of the tissues. In NP, changes in sensitization are persistent, causing spontaneous pain with a low stimulus threshold and even an onset or an increase of the pain with non-painful stimuli. This produces maladaptive changes on sensory neurons that can be irreversible (7, 14).

Some of the physiological changes that are produced in the peripheral area are electrical hyperexcitability and abnormal impulses (ectopic electrogenesis) (15) generated in the axon and in the injured primary sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglion (7). Ectopia leads to spontaneous firing in some neurons and abnormal responses to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli in many other neurons. The remodeling of voltage-sensitive ion channels, transducer molecules, and receptors in the cell membrane seems to be the cellular mechanism that underlies ectopic hyperexcitability (15). Na+ and K+ specific channels seem to have the greatest responsibility because they are directly involved in the repeated neuronal firing. Na+ channels accumulate in the membrane of injured nerve areas and in demyelination areas, the synthesis of the subtypes is increased, and its individual contribution could be increased by the mediators of hyperalgesia. In addition, this leads to a downregulation and to the block of K+ channels. The ectopic discharge contributes to NP as it generates a direct afferent signal and it can trigger and maintain central sensitization (15). Moreover, this causes the sensitization of nociceptors, the presence of ephapses, and abnormal interaction among fibers. At a central level, neurons of the posterior horn are sensitized and descending pain inhibitory mechanisms are altered (7).

LNP is also characterized by peripheral hyperexcitability, with overexpression of sodium and TRPV family 1 channels, which are located on nerve cell membranes. The analgesic effect of topical drugs used for NP treatment is particularly related to such channels, which are widely distributed on the surface of superficial or epidermal nociceptive fibers (16).

NP syndrome occurs as a complex combination of symptoms with interindividual variance that depends on the underlying pathophysiological changes resulting from the convergence of multiple etiological, genotypic, and environmental factors (7).

2.1 Medical signs of LNP

NP can present negative signs (e.g. sensory loss) or positive signs (e.g. abnormal neurosensorial responses). Somatization and sleep problems are also common, as well as mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. Negative signs are the first ones in determining that the somatosensory system is damaged. Positive signs can be either spontaneous (e.g. spontaneous pain, dysesthesia, paraesthesia) or evoked (e.g. allodynia, hyperalgesia, hyperpathia) (7). Table 2 shows the most relevant medical signs.

- Diagnosis

NP and LNP follow the same diagnosis. According to authors such as Finnerup et al. (17) and the IASP (1), if a patient suffers from a pain that could be the result of a neurologic lesion or disease instead of a lesion in the tissue, it must be classified as a possible, probable or definite pain.

3.1. Possible neuropathic pain

Firstly, the patient’s health record must be checked searching for a neurologic disease or lesion. The health record must show the pain history, suffered diseases, and existing comorbidities. In order to determine the pain level suffered by the patient, a visual analogue scale or a numerical scale can be used (18), as well as other scales or questionnaires (17, 19). Electrophysiological techniques such as electromyography (EMG), nerve conduction study or small fibre tests can be carried out (7). A physical examination is advisable to locate the painful area (18). In order for a patient to be diagnosed with possible LNP, two criteria must be met: (1) the potential existence of a serious neurologic problem (e.g. ictus, diabetic neuropathy) must be checked, and (2) the anatomical location of the pain must be determined in order to decide if it is compatible with the location of the lesion in the central or peripheral somatosensory nervous system (17). Pain can appear immediately or insidiously, depending on the lesion or disease, and the time relationship is relevant for the diagnosis (17).

3.2. Probable neuropathic pain

In this case, enough clinical support is needed to confirm what has been previously found. Despite the existence of positive signs, negative signs will determine LNP diagnosis (17). Table 3 shows positive and negative signs of NP.

In order for a patient to be diagnosed with probable LNP, the following scales and questionnaires must be positive: the LANSS scale, the Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire, the DN4 questionnaire, painDETECT or ID-Pain (17). Currently, there is a new specific tool for LNP called Diagnostic Tool, which enables to determine the localized character of NP (4) and which must also be positive to ascertain that NP is probable.

3.3. Definite neuropathic pain

The diagnosis must be based on medical imaging techniques which describe the lesion in the somatosensory nervous system, including: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan (17), neurophysiological tests (e.g. EMG, nerve conduction) (4), evoked potentials, quantitative sensory testing (QST), and withdrawal reflexes, among others. It should be noted that there can be other pain causes, and experts may not know if there is a direct causality (17). Figure 1 shows a diagnostic algorithm facing NP.

- Treatment

4.1. Pharmacological treatment

Pharmacological treatment for chronic illnesses has the disadvantage of a long-term low compliance by patients with the treatment. In addition, the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment for NP is limited, and only 40% of the patients experience a significant relief (16). Topical targeted treatment is administered for LNP, mainly 5% lidocaine and 8% capsaicin (3).

4.1.1. 5% lidocaine

5% lidocaine patches are a first-line treatment. They present a pharmacological action through lidocaine and a protective action by means of the patch, which acts as a physical barrier before the stimuli causing hyperalgesia (21). Lidocaine carries out a non-selective blockade of Na+ channels, and it attaches to the pores of the small local fibres damaged. This blockade halts signal propagation. Nevertheless, the final action will depend on the affinity and the binding rate of the drug, since there is not a complete sensory blockade of Na+ channels (21). Lidocaine patches reduce allodynia and NP symptoms (3).

The half-life of lidocaine is 7.6 hours. Therefore, it must be administered every 24 hours to keep its analgesic effect (16). The most common adverse effects of lidocaine are erythema, burning sensation, rashes, edema, and dermatitis, and they are limited to the application area (16).

4.1.2. 8% capsaicin

When neuropathy is caused by post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) or the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), capsaicin patches have been given the level A of efficiency by the European Federation of Neurological Sciences (16). Capsaicin interacts with the afferent nerve fibres through the selective agonist affinity for TRPV1, mainly located in Aδ-fibres, C-fibres and intracellular organelles (16). Capsaicin action is mediated by the opening of the TRPV1 channel and the subsequent depolarization through Na+ and Ca2+, as well as Ca2+ liberation to the endoplasmic reticulum (22). The high concentration of Ca2+ blocks the afferent nerves selectively. Nociceptive pain symptoms improvement occurs between 6 and 12 weeks by using a single 8% capsaicin patch (23). The drug effects last up to 90 days, so it is administered every three months (16).

4.1.3. Other topical and non-topical targeted treatments

Several topical targeted treatments for LNP are not yet commercially available. One of them is ketamine, an N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor agonist that reduces the threshold of nerve transduction and central sensitization (16). Ketamine is not approved for LNP treatment, although its effectiveness has been demonstrated (3).

Dextromethorphan is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, marketed as an external patch whose function is to relieve both muscular and rheumatic pain (16). Another example is bupivacaine, which is a local anaesthetic that blocks Na+ channels, also marketed as a long acting patch that provides an anaesthetic effect for a period of up to 3 days after a single application. Its effect is compared to 5% lidocaine patches (24). Furthermore, diclofenac and ketoprofen are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) available as patches and creams to treat chronic pain (24). In addition, the use of μ fentanyl agonist opioids and the partial µ-agonist buprenorphine has not been tested in LNP, although its effectiveness has been demonstrated in chronic cancer cases and non-cancer pain (3).

On the other hand, oral antidepressants and antiepileptics are also recommended for LNP treatment. Although there are numerous antidepressant and antiepileptic drugs, rotigotine and amitriptyline are the only ones that have been evaluated to treat pain conditions. The most commonly used antiepileptic drugs in LNP treatment are gabapentin and pregabalin, both administered orally (24).

In conclusion, the 5% lidocaine patch and the 8% capsaicin patch are the only topical dressings that are specific for treating LNP nowadays (16).

4.2 Non-pharmacological treatment

As of today, there is little evidence of the use of non-pharmacological treatment for LNP. However, the few existing data recommend its use as an attempt to reduce the use of medications and improve patients’ quality of life (25).

4.2.1 Interventional therapies

Spinal cord stimulation is a low-intensity electrical stimulation of large myelinated Aβ-fibers that modulates the pain signals from non-myelinated C-fibers (26). It is not only the most commonly used neuromodulation strategy, but also the most researched. It is based on the application of a monophasic square-wave pulse, which causes paresthesia in the affected region. New types of stimulation, such as burst and high frequency stimulation, can produce a stimulation without paresthesia and an equal pain relief compared with the monophasic square-wave pulse. These techniques are relatively safe, and their long-term effectiveness has been demonstrated by randomized controlled trials and several cases (26).

Dorsal root ganglion intervention, peripheral nerve intervention, and peripheral nerve field stimulation are three therapies based on the neurostimulation of afferent fibres outside the spinal cord and the subcutaneous stimulation of the peripheral nerve area. A cohort research reported that stimulation provided about 50% of pain reduction. (26)

Epidural motor cortex stimulation (EMCS), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of central motor cortex at levels below the motor threshold (27) can reduce thalamus hyperactivity or activate descending inhibitory pathways. Data appear to indicate that 60% of patients respond to EMCS (28).

Moreover, the internal capsule, nuclei in the sensory thalamus, the periaqueductal gray substance, the motor cortex, the septum, the accumbens, the posterior hypothalamus, and the anterior cingulate cortex have been suggested as potential target areas in deep brain stimulation. However, the application of this technique is controversial due to the significant risks showed by the current evidence (26).

4.2.2 Physical therapies

Although there is little evidence of the effectiveness of physical therapy, there are signs indicating that physical exercise and movement representation techniques (i.e. treatments that use the observation or imagination of normal pain-free movements, like mirror therapy and motor imagery) are beneficial (29).

4.2.3 Psychological therapies

The main goal of these therapies is to promote pain management and to reduce its emotional consequences. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), whose purpose is to lead the patient to an “individual change”, is the most researched therapy. This treatment addresses mood, function (including disability) social engagement, and analgesia as an indirect target. There are not enough evidences of the effectiveness of these therapies in LNP treatment, so an in-depth research of this field is required (30).

- Discussion and future perspectives

Nowadays, we face multiple challenges in relation to LNP. It is very hard to make a correct diagnosis of LNP due to the lack of consensus regarding its definition. Although there are several debates going on between experts (5, 16), there is not a global consensus on the definition of LNP, making an adequate diagnosis difficult. Another problem that needs to be solved is knowing the specific treatments that could be useful against the different types of NP (3), since there are patients with a treatment that does not effectively adjust to their pathology. Further research on the pathophysiological characteristics of LNP could help in the development of new effective and specific treatments for this type of pain.

In conclusion, an in-depth study of LNP is required in order to increase our knowledge about it, focusing on three aspects: (1) a global consensus on its definition, (2) more research on its physiology, and (3) more research on the effective treatments for each type of NP.

These aspects could enhance the adequacy of treatments, improving their effectiveness and patients’ quality of life, given the chronicity of this condition.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition, IASP Press, Seattle, 1994. http://www.iasp-pain.org.

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008; 70(18): 1630-1635. Doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59

- Rey R. Tratamiento del dolor neuropático. Revisión de las últimas guías y recomendaciones. Neurolarg. 2013; 5(S1): S1–S7. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuarg.2011.11.004

- Torres LM, Galvez R, Calderon E. Guía para el abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico farmacológico del Dolor Neuropático Periférico Localizado (DNL). España: Asociación Andaluza del Dolor; 2017.

- Mick G, Baron R, Finnerup NB, et al. What is localized neuropathic pain? A first proposal to characterize and define a widely used term. Pain Manag. 2012; 2(1): 71-77. Doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.77

- Cruccu G, Truini A. A review of Neuropathic Pain: From Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Pain Ther. 2017; 6(1): 35-42. Doi: 1. 10.1007/s40122-017-0087-0

- Velasco M. Dolor neuropático. Med. Clin. Condes. 2014; 25(4): 625-634. Doi: 10.1016/S0716-8640(14)70083-5

- Amato F, Duse G, Consoletti L, et al. Efficacy and safety of 5% lidocaine-medicated plasters in localized pain with neuropathic and/or inflammatory characteristics: An observational, real-world study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017; 21(18): 4228-4235. https://www.europeanreview.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/4228-4235-5-lidocaine-medicated-plasters-in-localized-pain.pdf

- Baron R, Allegri M, Correa-Illanes G, et al. The 5% lidocaine-medicated plaster: its inclusion in international treatment guidelines for treating localized neuropathic pain, and clinical evidence supporting its use. Pain The 2016; 5(2): 149-169. Doi: 10.1007/s40122-016-0060-3

- Bhaskar A, Mittal R. Local therapies for localised neuropathic Pain. Rev pain. 2011; 5(2): 12-20. Doi:1177/204946371100500203

- Üçeyler N, Sommer C. High-dose capsaicin for the treatment of neuropathic pain: what we know and what we need to know. Pain Ther. 2014; 3(2): 73-84. Doi:1007/s40122-014-0027-1

- Allegri M, Baron R, Hans G, et al. A pharmacological treatment algorithm for localized neuropathic pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016; 32(2): 377-384. Doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2016.10.004

- Zur E. Topical treatment of neuropathic pain using compounded medications. Clin J Pain. 2014; 30(1): 73-91. Doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318285d1ba

- Kuner R, Flor H. Structural plasticity and reorganisation in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017; 18: 20-30. Doi: 1038/nrn.2016.162

- Devor M. Respuesta de los nervios a la lesión en relación con el dolor neuropático. En: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editores. Wall y Melzack Tratado del dolor. 5ª Ed. Madrid: Elsevier; 2007. 927-951

- Pickering G, Martin E, Tiberghien FL, Delorme CL, Mick G. Localized pain: an expert consensus on local treatments. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017; 11: 2709–2718. Doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S142630

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DL, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Freeman R, Hansson P, Nurmikko T, Raja SN, Rice AS, Serra J, Smith BH, Treede RD, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016; 157(8): 1599-606. Doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000492

- Fernández R, Ahumada, M et al. Guía para definición y manejo del dolor neuropático localizado: Consenso Chileno. El Dolor. 2011; 55: 12-31. https://www.ached.cl/upfiles/revistas/documentos/4fe37b78dcb16_dnl_55.pdf

- Martínez-Salió A, Gómez A, Ribera MV, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento del dolor neuropático. Med Clin. 2009; 133(16): 629–636. Doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2009.05.029

- Correa-Illanes G. Dolor Neuropático, clasificación y estrategias de manejo para médicos generales. Revista clínica médica las condes. 2014; 25(2): 189-199

- Sheets MF, Hanck DA. Molecular action of lidocaine on the voltage sensors of sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2003; 121(2): 163–175. Doi: 1085/jgp.20028651

- Derry S, Lloyd R, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Topical capsaicin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (4): CD007393. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub2

- Sawynok J. Topical analgesics for neuropathic pain: preclinical exploration, clinical validation, future development. Eur J Pain. 2014; 18(4): 465–481. Doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00400.x

- Lodge D. The history of the pharmacology and cloning of ionotropic glutamate receptors and the development of idiosyncratic nomenclature. Neuropharmacology. 2009; 56(1): 6–21. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.006

- Zilliox LA. Neuropathic pain. Continuum Minneap Minn. 2017; 23(2): 512–532. Doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000462

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017; 3: 1-19. Doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2

- Sukul VV., Slavin KV. Deep brain and motor cortex stimulation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014; 18(7): 1-5. Doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0427-2

- Lefaucheur JP. Cortical neurostimulation for neuropathic pain: state of the art and perspectives. Pain. 2016; 157: S81–S89. Doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000401

- Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 2: CD010152. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010152.pub2

- Dobson JL, McMillan J, Li L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014; 8: 1-9. Doi:3389/fncel.2014.00102

AMU 2019. Volumen 1, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

15/04/2019 22/04/2019 31/05/2019

Cita el artículo: Morato-Gabao C, Navares-López D, Pérez-Martínez R, Romero-de-los-Reyes L, Solier-López L. Dolor neuropático localizado: una revisión narrativa. AMU. 2019; 1(1): 139-77