Juan Jesús Pérez-Núñez 1; Pablo Olea-Rodríguez 1; Rafael Manuel Palacios-López 1

1 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Celia Martínez-Coronado 2; África Morillas-Steveaux 2; Sergio Ruiz-Martos 2; Mario Sánchez-Cortés-Macías 3; Miguel Sillero Romero 2; Pablo Torregrosa-Parra 4; Diego García-Vergara 5

2 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

3 Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Liège (ULiège)

4 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB)

5 Faculty of Humanities, University Pablo de Olavide (UPO)

Introducción

El cólico renal (CR) de etiología litiásica es una causa frecuente de asistencia al servicio de urgencias en nuestro medio. El diagnóstico suele basarse en la clínica del paciente, pero a veces es necesario realizar pruebas de imagen complementarias. La tomografía computarizada de abdomen y pelvis es la prueba gold standard para confirmar el CR por litiasis, pero expone al paciente a altas dosis de radiación. Por ello, es necesario implementar y analizar el rendimiento de otras pruebas de imagen como la ecografía abdominal (EA), que está adquiriendo cada vez un papel más importante en la práctica clínica.

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el papel de la EA ante la sospecha de CR complicado por litiasis y el uso de otras pruebas de imagen en la práctica clínica real.

Metodología

Se trata de un estudio retrospectivo observacional de una cohorte de pacientes a los que se solicitó una EA por sospecha de CR complicado desde el servicio de urgencias de un hospital de tercer nivel. Se analizaron distintas variables relacionadas con la clínica del paciente, las pruebas realizadas y los hallazgos de imagen. Se realizaron análisis descriptivos y analíticos de las variables principales de interés: diagnóstico positivo, uso de protocolos de baja dosis de radiación, asociación entre la intensidad del dolor y otras variables relevantes.

Resultados

En este estudio analizamos un total de 80 pacientes. Se realizó radiografía a 64 de ellos (80 %). De las radiografías realizadas, el urgenciólogo evaluó el 90,6 % y diagnóstico litiasis en un 7,8 %, mientras que el radiólogo evaluó el 34,4 % y realizó el diagnóstico en un 18,8 %. La EA confirmó la existencia de litiasis en el 43,8 % de los pacientes. La tomografía computarizada (TC) se realizó de forma complementaria y diagnosticó litiasis en el 38,8 % de los pacientes, de los cuales un 90,3 % no tenían diagnóstico de litiasis previo. Al 48,3 % de éstos, se le aplicó protocolo de bajas dosis, encontrándose diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la dosis media de radiación recibida respecto a los casos en que no se aplicó dicho protocolo. No se encontró asociación significativa entre la intensidad del dolor del cuadro clínico ni haber tenido litiasis previas con el resultado ecográfico.

Conclusión

La EA es una prueba no invasiva que ofrece buenos resultados diagnósticos ante la sospecha de CR complicado. Aunque los protocolos de baja dosis de radiación en TC se emplean con cierta frecuencia ante la sospecha de CR complicado, es necesario implementar protocolos de actuación que garanticen el adecuado uso de esta prueba de imagen en la práctica clínica.

Palabras clave: urolitiasis, cólico renal, ecografía, tomografía computarizada, urgencias.

Keywords: urolithiasis, renal colic, ultrasound, computed tomography, emergency department.

Introducción

El cólico renal (CR) es una patología aguda caracterizada por la aparición brusca de un dolor intenso en el ángulo costovertebral, que puede ser localizado o irradiado hacia la zona inguinal (1, 2). La causa más frecuente de esta patología es la obstrucción del tracto urinario por un cálculo (urolitiasis). El más prevalente es el compuesto por calcio (3). La litiasis constituye entre el 2-5 % de las urgencias hospitalarias. Es la patología urológica urgente más frecuente (4) y afecta al 5-10 % de la población, presentando una alta tasa de recurrencia (5).

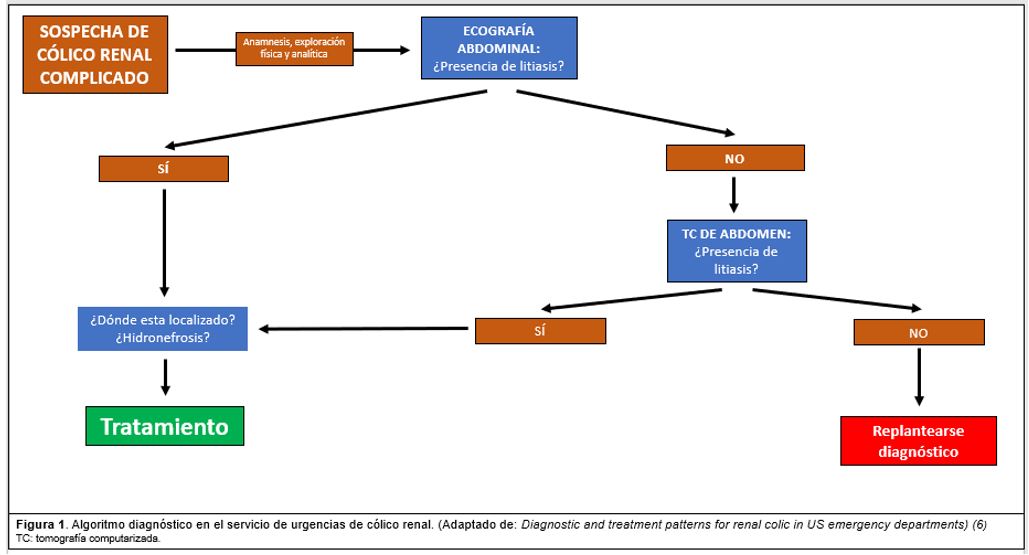

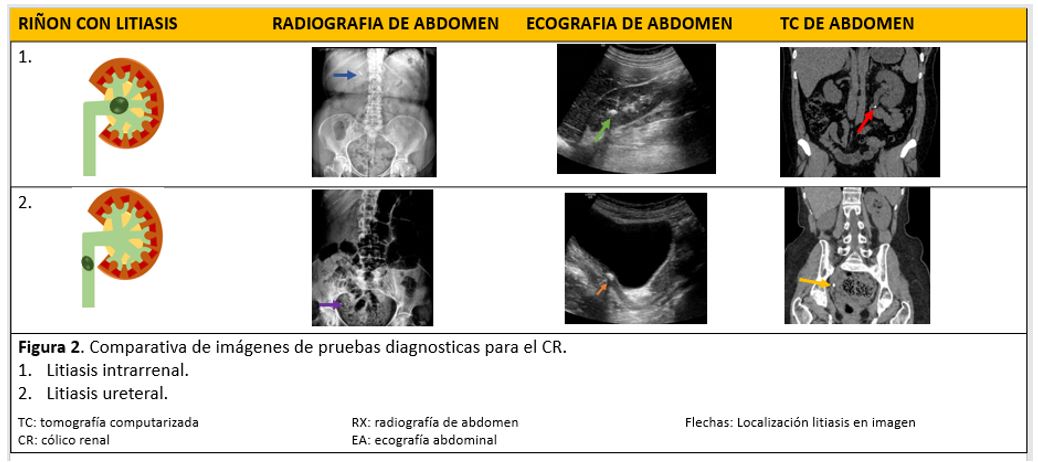

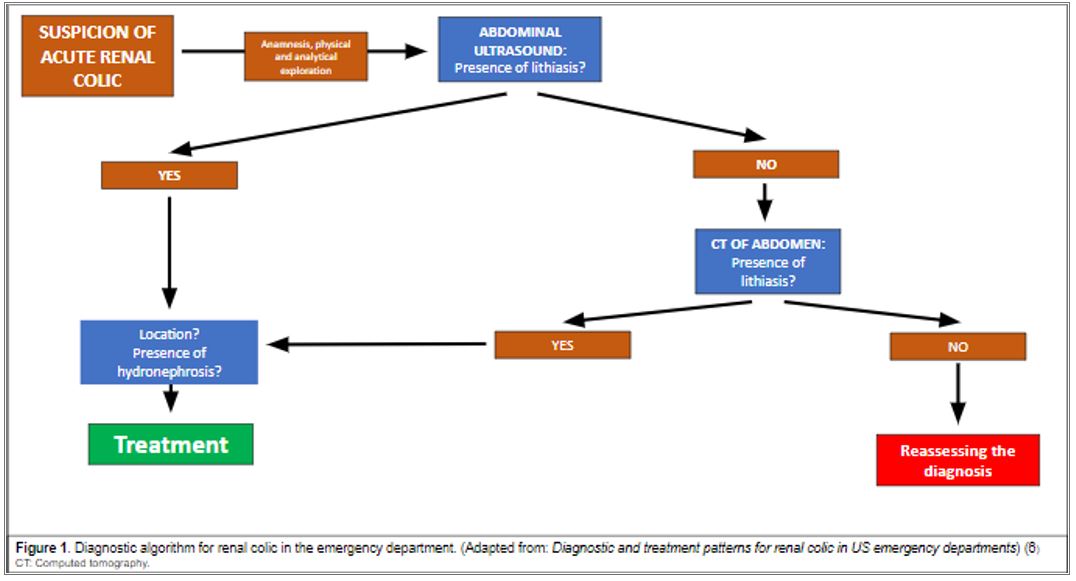

El cuadro clínico típico del paciente a su llegada al SU consiste en dolor de inicio brusco en flanco o irradiado a ingle. Puede estar acompañado de hematuria, síndrome miccional (2) y, con menos frecuencia, síntomas gastrointestinales (náuseas o vómitos) o fiebre, entre otros (1). Para considerarlo como CR complicado, debe contener alguno de los siguientes criterios: fiebre, deterioro de la función renal (creatinina >1,5mg/dL), hidronefrosis III-IV, cólico bilateral, riñón único o trasplante renal, dolor no controlado con medicación o embarazo (1, 6) (Figura 1).

El diagnóstico de urgencias del CR se basa en tres características: historia clínica, sedimento urinario y pruebas de imagen (4). Estas últimas son fundamentales para el diagnóstico, ubicación, tamaño y dureza de la litiasis, permitiendo precisar las opciones terapéuticas. Las más utilizadas son la radiografía simple, ecografía abdominal (EA) y tomografía computarizada (TC) de abdomen y pelvis (7). Al paciente con sospecha de CR se le realiza de forma sistemática en urgencias un sedimento de orina y una radiografía de abdomen. En función de los resultados y la evolución de la clínica se valora si se trata de un CR no complicado o complicado (4).

La TC es considerada la prueba gold standard que permite un mejor estudio del cálculo que la EA, y, por tanto, aporta más información a la hora de tomar una decisión terapéutica; sin embargo, a diferencia de la EA, esta prueba somete al paciente a altas dosis de radiación (13-20 mSv), lo que complica su uso rutinario debido a la alta tasa recidivante de la enfermedad (2,6–11). Por ello, existen protocolos de baja dosis de radiación para reducir la exposición a la mínima necesaria para obtener una imagen diagnóstica aceptable, con dosis medias de 6,1 mSv (11). La dosis efectiva para la TC de abdomen y pelvis está en torno a 7,7 mSv (12). La EA soluciona este problema, pero presenta otras limitaciones como la necesidad de experiencia técnico-práctica del profesional que la realiza, el tamaño del cálculo (si es muy pequeño puede no visualizarse) o el hábito o morfotipo del paciente, entre otras (13).

La EA es la prueba de imagen inicial recomendada por diversas guías clínicas ante la sospecha de CR complicado cuando la radiografía de abdomen es ineficaz o se necesita valorar el grado de hidronefrosis u otra complicación (7, 10). Sin embargo, en el escenario de la práctica clínica habitual existe una importante variabilidad en la elección y utilización de pruebas de imagen ante la sospecha de CR (14, 15). En ocasiones no se valoran adecuadamente las radiografías de abdomen o la técnica radiográfica no es la adecuada. Del mismo modo, la decisión de realizar TC o ecografía es en ocasiones errática o condicionada por diversos aspectos. Por un lado, la sobrecarga del radiólogo de guardia hace que se tomen decisiones basadas en características como el fenotipo del paciente o el grado de sospecha clínica, entre otros. Por otro lado, la decisión de realizar una TC complementaria cuando la EA no evidencia uropatía obstructiva litiásica no suele estar protocolizada en la rutina, ni se usan de forma sistemática protocolos de baja dosis de radiación (16).

Se dispone de escasos estudios en la literatura que analicen la utilización y el rendimiento de las pruebas de imagen ante la sospecha de CR en la práctica clínica habitual. Por ello, el objetivo principal de este trabajo es analizar el papel de la EA ante la sospecha de CR complicado en la práctica clínica habitual, así como el papel de otras pruebas de imagen. Como objetivos secundarios se persigue describir las variables clínicas y analíticas de la cohorte, valorar la utilidad diagnóstica de las pruebas de imagen en estos pacientes por parte del médico de urgencias y el radiólogo, y estudiar asociaciones de potencial interés, como la relación entre el índice de masa corporal (IMC) elevado y diagnóstico de litiasis con EA.

Metodología

Se realizó un estudio retrospectivo observacional siguiendo la guía STROBE (Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) (17). De forma retrospectiva se revisaron todos los casos a los que se realizó una EA por sospecha de CR complicado solicitada desde el servicio de urgencias del Hospital Virgen de las Nieves desde el 1 de septiembre hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2020. Se excluyen pacientes embarazadas y menores de 18 años. El estudio contó con la aprobación del comité de ética provincial de Granada (código 1235-N-20).

A la hora de conformar la base de datos, se utilizó la herramienta Excel del programa Microsoft 365®. Se incluyeron datos de laboratorio obtenidos en el SU: hematíes en sedimento, creatinina, leucocitos y proteína C reactiva. La historia clínica del episodio: localización e intensidad del dolor en el momento de solicitar la prueba de imagen (medido por escala EVA (escala visual analógica)), lado afectado, presencia o no de cortejo vegetativo y existencia de CR previo. También se incluyeron datos de la radiografía: si se realiza, valoración del médico o radiólogo, si se ve o no litiasis; y variables relacionadas con la EA (presencia de repleción vesical, visualización, localización y tamaño de la litiasis y presencia o no de hidronefrosis). En los casos de realización de TC: uso o no del protocolo de bajas dosis de radiación y la dosis efectiva, además de las mismas variables que para la EA, excepto la repleción vesical.

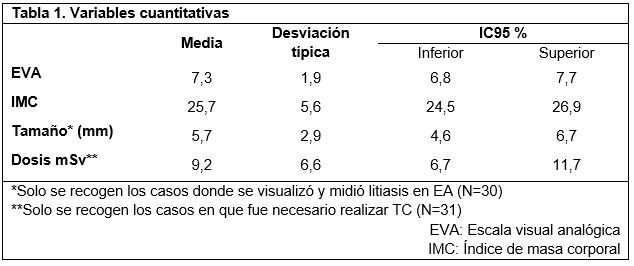

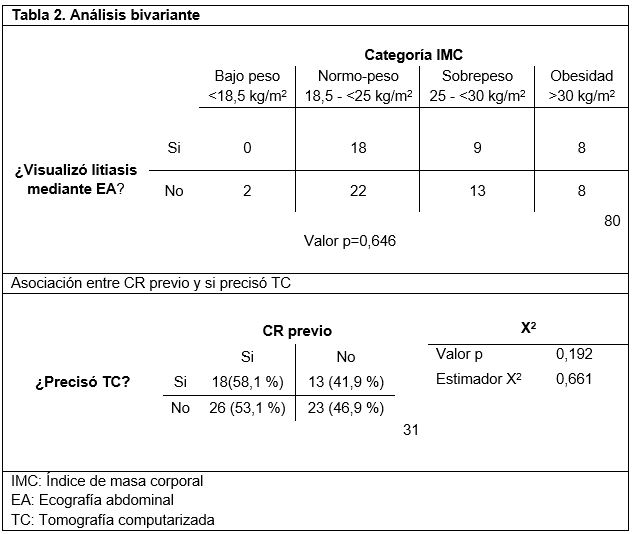

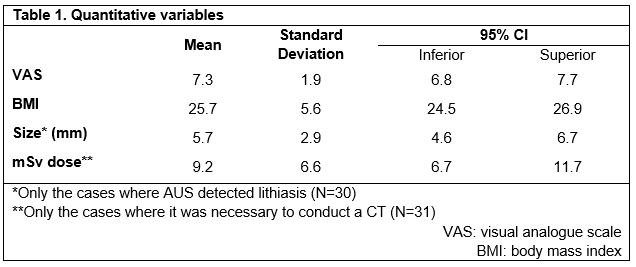

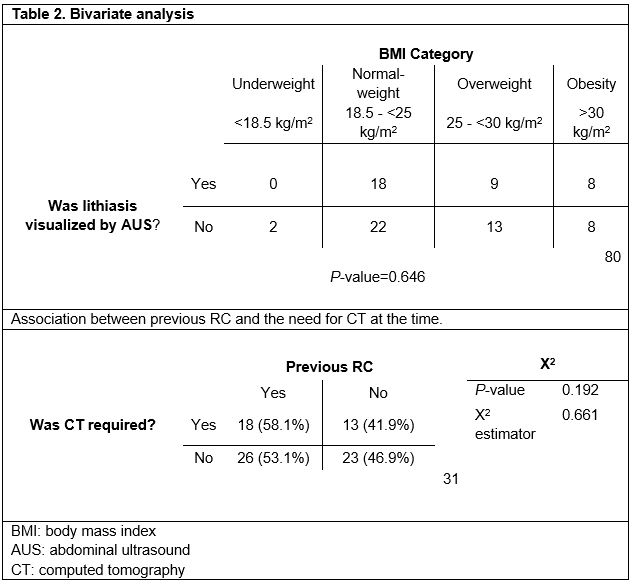

Todas las variables de la base de datos se analizaron estadísticamente mediante el programa SPSS versión 23.0®. Además, se calculó el índice de masa corporal (IMC) y su categorización posterior: bajo peso (<18,5kg/m2); normopeso (18,5 – <25kg/m2); sobrepeso (25 – <30kg/m2) y obesidad (>30kg/m2) (18). Parte de las variables cuantitativas se expresaron mediante la mediana y la desviación típica (tabla 1). Se realizaron análisis estadísticos bivariantes: T de Student de comparación de dos medias para valorar si existen diferencias significativas entre el dolor evaluado mediante EVA y la detección de litiasis; y el test χ2 para analizar la relación entre “CR previo”, “realización de TC” e “IMC” y “diagnostico por EA”. Dichos datos se pueden observar en la tabla 2.

Resultados

Características de la muestra

La cohorte es de 80 pacientes a los que se realizó EA por sospecha de CR complicado, 49 (61,3 %) hombres y 31 (38,8 %) mujeres, con un IMC medio de 25,73kg/m2 (s=5,9; valor mínimo: 16,4; valor máximo: 49,2), y un EVA medio de 7,26 (s=1,95). A un total de 31 pacientes (38,8 %) se les realizó una TC para confirmar el diagnóstico, con una dosis media de 9,19 mSv (s=6,57). El protocolo de baja dosis de radiación se aplicó a 15 pacientes (48,3 % de las TC realizadas). El tamaño medio de las litiasis vistas en EA fue de 5,67 mm (s=2,87). El análisis descriptivo de las variables IMC, escala EVA, dosis efectiva de radiación media (mSv) y tamaño litiasis se encuentran recogidas en la tabla 1. El resto de las variables medidas no se tuvieron en cuenta para el objetivo de este estudio.

Uso de la radiografía de abdomen

Se realizó radiografía de abdomen a 64 (80 %) pacientes de la muestra, de las cuales el 90,6 % fueron valoradas por el médico de urgencias, pero solo visualizaron la litiasis en un 7,8 %. De las radiografías que examinó el radiólogo (34,4 % del total de la muestra), se informó de la existencia de litiasis en el 18,8 % y signos dudosos de litiasis en un 15,6 %.

Capacidad diagnóstica de la EA

La EA identificó litiasis obstructiva en 35 (43,8 %) pacientes. De ellos, el 62,9 % estaba localizada en uréter distal con un tamaño medio de 4,5mm (s=2), el 5,7 % se encontraba en uréter medio con un tamaño medio de 7,5mm (s=4,5) y el 28,6 % se localizaba en uréter superior con un tamaño medio de 7,98mm (s=2,5). Un 2,9 % no se recogió en la base de datos (casos perdidos).

Influencia del IMC en el diagnóstico por EA

De nuestra población de estudio, 2 pacientes (2,5 %) tienen bajo peso, 40 (50 %) de ellos presentaban normopeso, 22 (27,5 %) tenían sobrepeso y los 16 restantes (20 %) obesidad. Al relacionar por categorías el IMC y si se visualizó litiasis en EA, a los pacientes que pertenecían al grupo “bajo peso” no se les diagnosticó litiasis por EA. Para el grupo “normopeso”, en el 45 % (18 pacientes) sí se visualizó litiasis con EA, mientras que en el 55 % (22 pacientes) restante no. De los pacientes que formaban el grupo “sobrepeso”, en el 40,9 % (9 pacientes) sí se visualizó la litiasis, mientras que al 59,1 % (13 pacientes) no. De los 16 pacientes restantes pertenecientes al grupo “obesidad”, en el 50 % (8 pacientes) se pudo visualizar la litiasis y en el 50 % (8 pacientes) restante no. El test χ2 no mostró diferencias significativas entre grupos (p=0,646).

Casos que necesitaron TC tras EA

De los pacientes de nuestra cohorte, a 31 (38,8 %) se les realizó TC para completar el estudio de urolitiasis, que fue diagnóstica en todos los casos. De estos, en 28 casos (90,3 %) no fue posible llegar al diagnóstico únicamente con la EA, mientras que en los otros 3 (9,7 %), sí se visualizó la litiasis con la EA, pero necesitaron la realización de una TC para completar el estudio por otras razones. A 17 (37,8 %) pacientes en los que no se visualizó litiasis en EA no se le realizó TC para completar el diagnostico.

Aplicación de protocolo de baja dosis.

Dentro del grupo al que se realizó TC complementaria, se aplicó el protocolo de baja dosis a 15 (48,4 %) pacientes, los cuales recibieron una dosis de radiación media de 5,49 mSv (s=4) y no se aplicó dicho protocolo a 16 (51,6 %) pacientes, de los cuales solo están recogidos los datos de radiación de 13 (81,5 %), recibiendo una dosis media de 13,46 mSv (s=6,4). El test t de Student demostró diferencias significativas entre las dosis medias de radiación recibidas entre ambos grupos (p<0,001).

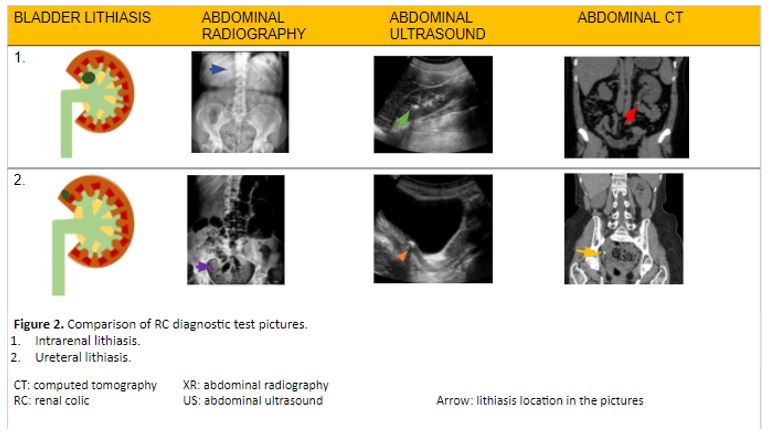

A modo de resumen, la figura 2 muestra una comparativa de las pruebas de imagen (radiografía, EA y TC) en el diagnóstico del CR en el servicio de urgencias.

Discusión

Los resultados de nuestro estudio son interesantes. En primer lugar, el médico de urgencias sólo identificó un 7,8 % de urolitiasis en la radiografía simple de abdomen frente al 18,8 % de casos en que el radiólogo identificó la litiasis. La escasa identificación de CR por el médico de urgencias en la radiografía de abdomen podría estar justificada, además del menor entrenamiento en comparación con el radiólogo, por el tamaño de la piedra, ya que se ha descrito la asociación entre un tamaño mayor de litiasis con la sensibilidad (50 %) de la radiografía de abdomen para poder visualizar litiasis (19). Cuando el tamaño es menor de 5 mm, la sensibilidad de la radiografía disminuye a un 23,6 %. El tamaño medio de las piedras de nuestro estudio diagnosticado por la EA es de 5,6 mm. Este tamaño justificaría una reducción de sensibilidad de la radiografía en la detección de la urolitiasis. Sea como fuere, los resultados obtenidos sugieren que debería favorecerse la interconsulta al radiólogo para facilitar el diagnóstico de litiasis renal, ya que podría evitar la realización de pruebas innecesarias, particularmente en casos donde la litiasis es de pequeño tamaño y localización distal.

No se encontraron diferencias significativas en el diagnóstico de litiasis mediante EA en función de las categorías convencionales del IMC, lo que sugiere que la EA podría ofrecer un rendimiento diagnóstico similar, independientemente del morfotipo del paciente. Sin embargo, el reducido tamaño muestral del estudio exige comprobar esta hipótesis mediante estudios más amplios, idealmente prospectivos.

Las urolitiasis diagnosticadas por EA en nuestro estudio tienen un tamaño medio de 5,67 mm. Existen estudios comparativos que remarcan la desventaja de la EA respecto a la inexactitud del propio diagnóstico de la urolitiasis y del tamaño de la litiasis (13). Estos estudios muestran que el diagnóstico por EA tiene una tendencia a sobreestimar el tamaño de las piedras menores de 5 mm. Incluso Ganesan V et al. (20), indican que hay una sobreestimación significativa en piedras de hasta 10mm. Dicha sobreestimación puede mostrar un aumento del tamaño de las piedras de 2,2mm de media en las litiasis renales. Esta cuestión no es insignificante, pues en función del tamaño del cálculo se determina un modo de actuación clínica, por lo que una sobreestimación del tamaño puede llevar a una toma de decisión clínica inadecuada para el paciente. Algunos estudios muestran que el uso de EA lleva a una toma de decisión terapéutica inadecuada en 1 de cada 5 pacientes diagnosticado por EA (20).

Smith R et al. (21) observaron que aquellos pacientes que fueron sometidos a EA reciben de media una radiación significativamente menor que los pacientes que se someten a TC (10,1 mSv y 9,3 mSv, respectivamente, frente a 17,2 mSv). Sin embargo, confirmaron un aumento en la necesidad de pruebas adicionales en aquellos pacientes que se les realizó de entrada una EA En nuestro estudio también se observó este hecho, ya que un 38,8 % de los pacientes tuvieron que someterse secundariamente a una TC por no poder diagnosticarlos de CR con la EA. La necesidad de realizar una TC para precisar con mayor exactitud el tamaño y presencia de un cálculo en pacientes con CR (13) supone irradiarlo (a menudo en varias ocasiones), con los peligros que esto implica para su salud, fundamentalmente en relación con el cáncer radioinducido (5). Tal y como señalaron Rob S. et al. (22), el uso frecuente de pruebas de imagen radiológicas en aquellos sujetos que tienen recidivas de CR hace que la dosis de radiación administrada a cada paciente supere la dosis recomendad anual, apoyando nuestra idea de promover más el uso de la EA ante la sospecha de CR complicado frente a la TC para evitar este exceso de radiación. Rob et al. definen como dosis baja <3,5 mSv y dosis ultrabaja ≤1,9 mSv, una dosis de radiación que está bastante lejos de la dosis que se empleó de media en nuestro estudio (9,19 mSv). No obstante, si se tiene en cuenta únicamente a los pacientes en que se aplicó el protocolo de baja dosis de radiación, las dosis efectivas son similares (dosis media: 5,49 mSv). Este aspecto es relevante, especialmente si se tiene en consideración que no se vio afectada la capacidad diagnóstica de la TC, lo que apoya la importancia de utilizar estos protocolos de baja dosis de radiación. No obstante, es preciso verificar este extremo mediante estudios específicos.

Como limitaciones en nuestro estudio, cabe destacar el reducido tamaño de muestra (lo que dificulta la posibilidad de establecer asociaciones extrapolables a la población general), la ausencia de algunas variables que habrían resultado de interés (motivo por el que se realiza TC, motivo por el que se aplica protocolo bajas dosis, tipo de tratamiento tras diagnóstico), el carácter unicéntrico (que limita la validez externa del estudio), así como la existencia de datos perdidos por una inadecuada recogida de datos por parte del personal de urgencias. Muchas de estas limitaciones obedecen al carácter eminentemente práctico y descriptivo del estudio. En futuros trabajos sería beneficioso definir una nomenclatura común a la hora de recoger los datos referidos a la localización anatómica de la litiasis. Entre otros aspectos, esto podría utilizarse para asociar la intensidad del dolor del CR con la localización de la litiasis.

Conclusión

La capacidad diagnostica de CR mediante EA en nuestro estudio fue aceptable, aunque se requirió el concurso de la TC (gold standard) de forma complementaria en un porcentaje significativo de los casos. El aumento de la importancia de la EA en el diagnóstico de CR es evidente de acuerdo con la literatura científica, pero aún es necesario mejorar ciertos aspectos como es la formación del personal que realiza la prueba. Resulta fundamental evitar las inexactitudes de la EA en el diagnostico puesto que puede orientar a un plan terapéutico erróneo e inadecuado manejo clínico del paciente. Por otro lado, la radiografía simple de abdomen tiene una sensibilidad muy condicionada por el tamaño de la piedra, en piedras pequeñas el diagnóstico es muy limitado. Sin embargo, el radiólogo, a pesar de esta limitación, diagnostica más urolitiasis que el médico de urgencias, por lo que debería favorecerse la interconsulta a estos especialistas para facilitar el diagnóstico. No se ha encontrado relación entre un IMC alto con una menor capacidad de visualizar urolitiasis en EA, lo que apoyaría la utilización de esta técnica en pacientes con IMC elevado, a pesar de que existen guías clínicas que aconsejan el uso de TC como prueba de imagen inicial en este grupo de pacientes.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», especialmente a Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos-Bossini por la aportación de las imágenes radiológicas, así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Consideraciones éticas

Este trabajo cuenta con la aprobación del Comité Ético de Investigación Provincial de Granada (código 1235-N-20).

Referencias

- Francisco Javier Ancizu FD-C. Cólico renal. [Internet]. [citado 29 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://docplayer.es/111525020-Colico-renal-francisco-javier-ancizu-fernando-diez-caballero.html

- Gary C Curhan, MD S, Mark D Aronson M, Glenn M Preminger M. Diagnóstico y manejo agudo de la sospecha de nefrolitiasis en adultos – UpToDate [Internet]. [citado 5 de marzo de 2021].

- Singh P, Enders FT, Vaughan LE, Bergstralh EJ, Knoedler JJ, Krambeck AE, et al. Stone Composition Among First-Time Symptomatic Kidney Stone Formers in the Community. Mayo Clin Proc [Internet]. octubre de 2015;90(10):1356-65. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26349951

- Sánchez-Carreras Aladrén F, Verdú Tartajo F, Herranz Amo F, Escribano Patiño G, María Díez Cordero J, Moncada Iribarren José Jara Rascón I, et al. URGENCIAS UROLOGICAS [Internet]; 2014 [citado 8 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.aeu.es/UserFiles/files/Urgencias_Urologicas.pdf

- Aller Rodríguez M, Álvarez Castelo L, Asensi Pernas A, Cabana Cortizas MT, Caeiro Castelao JM, Calvo Quintela L, et al. Abordaje práctico de la patología urológica [Internet]. María Sánchez J, Venancio M, Abal C, editores. EdikaMed, S.L; 2014 [citado 8 de marzo de 2021]. 277 p. Disponible en: www.cedro.org

- Brown J. Diagnostic and treatment patterns for renal colic in US emergency departments. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38(1):87-92.

- Susaeta R, Benavente D, Marchant F, Gana R. Diagnóstico y manejo de litiasis renales en adultos y niños. Rev Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2018;29(2):197-212.

- Fwu C-W, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Kirkali Z. Emergency department visits, use of imaging, and drugs for urolithiasis have increased in the United States. Kidney Int. marzo de 2013;83(3):479-86.

- Coursey CA, Casalino DD, Remer EM, Arellano RS, Bishoff JT, Dighe M, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® acute onset flank pain-suspicion of stone disease. Vol. 28, Ultrasound Quarterly. 2012.

- Mark L Zeidel M, W Charles O’Neill M. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of urinary tract obstruction and hydronephrosis – UpToDate [Internet]. 2021 [citado 5 de marzo de 2021].

- van der Molen AJ, Miclea RL, Geleijns J, Joemai RMS. A Survey of Radiation Doses in CT Urography Before and After Implementation of Iterative Reconstruction. Am J Roentgenol [Internet]. 1 de septiembre de 2015 [citado 29 de marzo de 2021];205(3):572-7.

- RadiologyInfo.org | Español [Internet]. [citado 29 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.radiologyinfo.org/sp/

- Smith D, Patel U. Ultrasonography vs computed tomography for stone size. BJU Int [Internet]. 1 de marzo de 2017 [citado 7 de marzo de 2021];119(3):361-2. Disponible en: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bju.13735

- Arrabal Martín M, Barrero Candau R, Campoy Martínez P, Carnero Bueno J, Del Río Urenda S. Urolitiasis: proceso asistencial integrado [Internet]. Junta de A. 2012 [citado 12 de marzo de 2021]. 230 p. Disponible en: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyfamilias/areas/calidad-investigacion-conocimiento/gestion-conocimiento/paginas/pai-urolitiasis.html

- Robledo Aburto ZA, Borja Aburto VH, Lira Romero JM, Arizmendi Urise E, Peña viveros R. Diagnostico y tratamiento del cólico renoureteral en el servicio de urgencias [Internet]. Durango 289-1A Colonia Roma; 2019 [citado 14 de marzo de 2021].

- Nicolau C, Salvador R, Artigas JM. Diagnostic management of renal colic. Radiología [Internet]. 57(2):113-22.

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth [Internet]. abril de 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31-4.

- F.Xavier P-S, D DMBS, Bouchard C, A R. The Practical Guide Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative [Internet]. 2000 [citado 29 de marzo de 2021]. 94 p.

- Jung SI, Kim YJ, Park HS, Jeon HJ, Park HK, Paick SH, et al. Sensitivity of digital abdominal radiography for the detection of ureter stones by stone size and location. J Comput Assist Tomogr, noviembre de 2010;34(6):879-82.

- Ganesan V, De S, Greene D, Torricelli FCM, Monga M. Accuracy of ultrasonography for renal stone detection and size determination: is it good enough for management decisions? BJU Int, marzo de 2017;119(3):464-9.

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, Bengiamin RN, Camargo CA, Corbo J, et al. Ultrasonography versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med., septiembre de 2014;371(12):1100-10.

- Rob S, Bryant T, Wilson I, Somani BK. Ultra-low-dose, low-dose, and standard-dose CT of the kidney, ureters, and bladder: is there a difference? Results from a systematic review of the literature. Vol. 72, Clinical Radiology. W.B. Saunders Ltd; 2017. p. 11-5.

Diagnosis of Acute Renal Colic by Imaging Tests: A Retrospective Observational Study

Introduction

Renal colic (RC) caused by lithiasis is a common reason for presentation to the emergency department. Its diagnosis is usually based on the patient’s clinical picture, but it is sometimes necessary to perform complementary imaging tests. Even though the patient is exposed to high radiation doses, computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis is the gold standard test to confirm RC by lithiasis. That is why it is necessary to implement and analyze the performance of other imaging tests such as abdominal ultrasound (AUS), which is increasingly becoming more important in clinical practice. The objective of this study was to evaluate the role of AUS in diagnosing a suspected acute RC by lithiasis and the use of other imaging tests in clinical practice.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study of a cohort of patients with suspected acute RC who underwent an AUS, as requested by the emergency department of a third-level hospital. Different variables related to the patient’s clinical picture, the performed imaging tests and their findings were analyzed. Moreover, both descriptive and analytical analysis of the main variables of interest were conducted: positive diagnosis, use of low radiation dose protocols, and association between pain intensity and other relevant variables.

Results

In this study, a total of 80 patients were analyzed. Of the 64 patients (80% out of the overall sample) who underwent an abdominal radiography (AR), the radiologist was able to detect lithiasis in 18.8% of patients (34.4%), whereas the emergency physician identified it in 7.8% of them (90.6%). The presence of lithiasis was confirmed by AUS in 43.8% of patients. CT was complementarily conducted, diagnosing lithiasis in 38.8% of patients, of whom 90.3% had not been previously diagnosed with lithiasis. A low radiation dose protocol was applied to 48.3% of the latter, and statistically significant differences were found between the mean radiation dose to which those patients were exposed and the one administered when such protocol was not applied. AUS results were neither significantly associated with the pain intensity of the patient’s clinical picture, nor with a previous diagnosis of lithiasis.

Conclusion

AUS is a non-invasive test that offers significant diagnostic results if acute RC is suspected. Low radiation dose protocols are employed in CT with certain frequency when the presence of acute RC is suspected. However, it is necessary to implement intervention protocols that guarantee the appropriate use of this imaging test in clinical practice.

Keywords: urolithiasis, renal colic, ultrasound, computed tomography, emergency department.

Introduction

Renal colic (RC) is an acute pathology characterized by the sudden onset of severe pain in the costovertebral angle. This pain can be located or radiated to the groin (1, 2). The most common cause of this pathology is the obstruction of the ureter by a stone (i.e. urolithiasis). Stones composed of calcium are the most recurrent (3). Lithiasis accounts for 2-5% of all clinical presentations to the emergency department. It is the most common urological emergency (4), affecting 5-10% of the population and presenting a high relapse rate (5).

Sudden pain located in the flanks or radiated to the groin is the most common clinical picture of the patient when treated in the emergency department. This pain can be accompanied by haematuria, urinary syndrome (2) and, less frequently, by gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea and vomiting) or fever, among others (1). To consider it as an acute RC, the patient must present any of the following: fever, renal insufficiency (creatinine >1.5mg/dL), moderate or severe hydronephrosis, bilateral renal colic, solitary kidney, having undergone a renal transplant, uncontrolled pain despite treatment, or pregnancy (1, 6) (Figure 1).

The diagnosis of RC in emergency care is based on three aspects: the patient’s medical record, a urinary sediment analysis, and imaging findings (4). Imaging tests are fundamental to diagnose lithiasis in terms of identifying the location, size and hardness of the stones. Consequently, imaging findings help determine the most appropriate therapeutic options to treat RC. The most common imaging tests performed are plain abdominal radiography (AR), abdominal ultrasound (AUS), and computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis (7). A urine sediment analysis and an AR are systematically performed on the patient with suspected RC. The results and the development of the patient’s clinical picture will be taken into consideration in order to assess if it is an acute RC or not (4).

CT is considered the gold standard test, as it enables a better examination of the stone than AUS does. Since CT provides more information, the therapeutic decision-making is more appropriate. However, the patient undergoing this procedure is exposed to high radiation doses (13-20 mSv) —unlike AUS— and its routine use is complicated because of the high relapse rate of this illness (2, 6, 7, 10, 11). Therefore, there are low radiation dose protocols to reduce the exposure to 6.1 mSv (11), which is the minimum radiation dose that enables diagnosis by imaging. The effective dose for CT of abdomen and pelvis is around 7.7 mSv (12). AUS solves this problem, but it presents other limitations such as the necessary technical and practical experience of the professional conducting it, the stone size —if it is too small, it may not be visible—, or the patient’s morphotype, among others (13).

Several clinical guidelines recommend AUS as the initial imaging test to be performed on patients with suspected acute RC when AR is anodyne, or the degree of hydronephrosis or other kind of complication must be assessed (7, 10). However, there is a huge variability in the choice and use of imaging tests when RC is suspected in the usual clinical practice (14, 15). Occasionally, ARs are not adequately assessed, or the radiographic technique used is not the most appropriate. Sometimes, the decision of conducting a CT or an AUS is likewise erratic and conditioned by different aspects. On the one hand, the work overload of the on-call radiologist leads to decisions based on aspects such as the patient’s phenotype and the degree of clinical suspicion, among others. On the other hand, when the diagnosis by AUS does not reveal the presence of hydronephrosis, a CT is complementarily performed, but this is not usually conducted in clinical practice. What is more, low radiation dose protocols are neither systematically applied in the performance of this complementary CT (16).

There are few studies that analyze the use and the performance of imaging tests for suspected RC in the usual clinical practice. For this reason, the main objective of this paper is to analyze the role of AUS and other imaging tests in diagnosing suspected acute RC in the usual clinical practice. The secondary objectives of this paper are to describe the clinical and analytical variables of the cohort of patients, and to assess the diagnostic value of the imaging tests that were performed on the patients by the emergency physician and the radiologist. Another secondary objective is to examine associations of potential interest for this research, such as the association between high body mass index (BMI) and the diagnosis of lithiasis by AUS.

Methods

An observational retrospective study was conducted following the STROBE guidelines (17). A retrospective review was made to all the patients who, presenting a suspected acute RC, underwent an AUS from 1st September 2020 to 31st December 2020. This imaging test was requested by the emergency department of Hospital Virgen de las Nieves (Granada, Spain). Pregnant and underage (<18) patients were excluded. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Province of Granada (code 1235-N-20).

The database was made in Microsoft Excel®. Laboratory data collected in the emergency department was included: sedimentary red blood cells, creatinine, leukocytes, and C-reactive protein. Data related to the pathology was also included: location and intensity of the pain at the time of requesting the imaging test, assessed by the visual analogue scale (VAS); injured area; presence of vegetative symptoms; and previous diagnosis of RC. In addition, the database contains data from the radiography: the doctor’s or radiologist’s assessment indicating if lithiasis was visible or not, and variables related to AUS performance (presence of vesical filling, visualisation, location and size of the stone, and presence of hydronephrosis). When conducting a CT, the following information was included: use of low radiation dose protocol if applicable and effective dose, as well as the same variables applied to AUS, excluding vesical filling.

All the variables of the database were statistically analyzed by using SPSS® Statistics 23.0. Furthermore, BMI and its subsequent categorization were calculated: underweight (<18.5kg/m2); normal-weight (18.5 − <25kg/m2); overweight (25 – <30kg/m2) and obesity (>30kg/m2) (18). Some quantitative variables were presented as the median and the standard deviation (Table 1). Two bivariate statistical analyses were undertaken. Firstly, the comparison by Student’s t-test of two means to assess if there were significant differences between the pain assessed by VAS and the detection of lithiasis. Secondly, the χ2 test to analyze the association between a previous diagnosis of RC and the performance of a complementary CT, and between the BMI and the detection of lithiasis by AUS. These data are included in Table 2.

Results

Sample characteristics

The cohort of patients with suspected acute RC, on whom an AUS was performed, was composed of 80 people —49 men (61.3%) and 31 women (38.8%)— with a mean BMI of 25.73kg/m2 (s=5.9; minimum value: 16.4; maximum value: 49.2), and a mean VAS of 7.26 (s=1.95). A CT was performed on 31 patients (38.8%) to confirm the diagnosis of RC, with a mean radiation dose of 9.19 mSv (s=6.57). The low radiation dose protocol was applied to 15 patients (48.3% of the conducted CT). The mean size of the stone detected by AUS was 5.67mm (s=2.87). A descriptive analysis of the following variables was undertaken: BMI, VAS scale, effective dose of mean radiation (mSv) and size of the stone (Table 1). The remaining variables were not taken into account because they were not significant for the objective of this study.

Use of AR

A total of 64 sample patients (80%) underwent AR. An emergency physician examined 90.6% of these radiographies, but lithiasis was only found in 7.8%. Among those analyzed by a radiographer (34.4% of the samples), lithiasis was reported in 18.8%, whereas inconclusive signs were found in 15.6%.

Diagnostic performance of AUS

Obstructive lithiasis was identified by AUS in 35 patients (43.8%). It was located in the distal ureter with a mean size of 4.5 mm (s=2) in 62.9% of the patients; in the middle ureter with a mean size of 7.5 (s=4.5) mm in 5.7%; and in the upper ureter with a mean size of 7.98 mm (s=2.5) in 28.6%. However, 2.9% was not included in the database (lost data).

BMI impact on AUS diagnosis

In our study population, 2 patients (2.5%) were underweight, 40 (50%) were normal-weight, 22 (27.5%) were overweight, and the remaining 16 (20%) were obese. Upon comparison of BMI categories and the presence of lithiasis in the AUS diagnosis, it was found that underweight patients were not diagnosed with lithiasis. Among normal-weight patients, lithiasis was found in 18 out of 40 (45%). In the overweight group, lithiasis was detected in 9 out of 22 (40.9%). As for the obesity group, lithiasis was detected in half of the patients. The χ2 test showed no significant differences among the four groups (p=0.646).

Cases needing CT after AUS

Among our cohort patients, 31 (38.8%) underwent a CT in order to complete the urolithiasis study, which was diagnosed in all the cases. Among these, it was not possible to diagnose it in 28 cases (90.3%) exclusively by AUS. As for the three remaining cases (9.7%), a CT was required to complete the study for other reasons, although it was possible to detect lithiasis by AUS. Among the 45 patients with undiagnosed lithiasis by AUS, 17 (37.8%) did not undergo a CT to complete the diagnosis.

Application of low radiation dose protocol

Within the group that underwent a complementary CT, 15 patients (48.4%) were exposed to a low dose with a mean radiation dose of 5.49 mSv (s=4). The remaining 16 patients (51.6%) were not exposed to this protocol. Among them, radiation data on only 13 patients (81.5%) were collected. These were exposed to a mean radiation dose of 13.46 mSv (s=6.4). The Student’s t-test showed significant differences between the average radiation doses in both groups (p<0.001).

As a summary, Figure 2 shows a comparison between imaging tests (AR, AUS, and CT) in diagnosing RC in the emergency department.

Discussion

Our study presents interesting results. To begin with, the emergency physician identified only 7.8% of urolithiasis cases by a plain AR, whereas 18.8 % of lithiasis cases were identified by the radiographer. The low number of RC cases identified by the emergency physician using AR might be explained by the size of the stone, apart from a poorer training compared to that of the radiographer. According to Sung Li Jung et al. (19), there is an association between a bigger size of the stone and the AR sensitivity (50%) to detect a case of lithiasis. Its sensitivity drops to 23.6% when the stone is smaller than 5 mm. The mean stone size diagnosed by AUS in our study is 5.6 mm. This would explain a decrease in the radiography’s sensitivity to detect urolithiasis. In any case, our results suggest that a cross-consultation with a radiologist should be facilitated so as to aid the diagnosis of renal lithiasis. This would prevent further unnecessary tests, particularly in cases where lithiasis has a small size and is located in the distal ureter.

No significant differences based on the conventional categories of BMI were found in lithiasis diagnosis by AUS, which suggests that this procedure could provide a similar diagnostic performance independently from the patient’s morphotype. However, the reduced sample size of our study requires wider studies, ideally prospective, in order to verify the strength of this hypothesis.

In our study, most urolithiasis diagnosed by AUS have a mean size of 5.67 mm. There are comparative studies that highlight the disadvantage of this procedure regarding the inaccuracy of the urolithiasis diagnosis itself and the size of the stone (13). These studies show that AUS diagnosis tends to overestimate the size of stones smaller than 5 mm. Even Ganesan V et al. (20) point out that there is a significant overestimation in stones up to 10 mm. Such an overestimation can show an increase in the size of stones up to 2.2 mm on average in renal lithiasis. This is not a trivial matter, as clinical management is determined according to the stone size. Therefore, a size overestimation could lead to an inadequate clinical decision for the patient. Some studies reveal that the use of AUS leads to inadequate therapeutic decision-making in 1 out of 5 patients diagnosed by AUS (20).

Smith R et al. (21) observed that patients that underwent AUS are exposed on average to significantly less radiation than those subjected to CT (10.1 mSv and 9.3 mSv, respectively, against 17.2 mSv). However, they confirmed an increase in the need for complementary tests in those patients who underwent AUS at first. The same fact was also observed in our study, as 38.8% of the patients had to undergo a complementary CT after being unsuccessfully diagnosed with RC by AUS. The need for a CT in order to determine with greater accuracy the presence and size of a stone in patients with RC (13) involves exposing patients to radiation (often in several occasions), alongside the dangers it entails for their health, mainly related to radiation-induced cancer (5). As pointed out by Rob S. et al. (22), the frequent use of radiological images in subjects suffering from RC relapses results in exceeding the yearly recommended dose of radiation administered to each patient. Therefore, it supports our idea of encouraging the use of AUS when a case of acute RC is suspected so as to avoid the radiation excess by CT. Low dose (<3.5 mSv) and ultra-low dose (≤1.9 mSv), as defined by Rob et al., correspond to a radiation dose far lower than the mean one used in our study (9.19 mSv). However, if only patients undergoing the low radiation dose protocol are taken into account, the effective doses are similar (mean dose: 5.49 mSv). This aspect is relevant, especially if the fact that the CT diagnostic capacity was not affected is considered. This supports the importance of using these low radiation dose protocols. Nonetheless, it is necessary to verify this matter through specific studies.

It must be noted that there are several limitations in our study. Firstly, the reduced sample size complicates the possibility to establish connections that can be extrapolated to the general population. Secondly, the absence of some potentially interesting variables, such as the reason why CT is performed, why the low dose protocol is administered, and the post-diagnosis type of treatment. Lastly, the study presents a single-center nature that limits the external validity of the study, and there are some lost data due to an inadequate data collection by the healthcare staff. Many of these limitations are due to the eminently practical and descriptive nature of the study. It would be beneficial to establish a common nomenclature in future studies when collecting data on the anatomical site of lithiasis. Among other aspects, this could be used to associate the RC pain intensity with the location of lithiasis.

Conclusions

The RC diagnostic capacity by AUS was acceptable, but the complementary use of CT (the gold standard test) was required in a significant number of cases. According to the scientific literature, the increase in the AUS importance during RC diagnosis is evident, but certain aspects, such as the training of the staff in charge of the test, need some improvements. It is essential to avoid AUS inaccuracies during the diagnosis, as it could lead to a mistaken therapeutic program and an inadequate clinical management of the patient. On the other hand, the plain AR sensitivity is remarkably conditioned by the stone size, as the diagnosis is very limited with small stones. Despite this limitation, the radiographer diagnoses more urolithiasis than the emergency physician, so cross-consultation with the former should be facilitated in order to aid the diagnosis. No associations between a high BMI and a lower ability to visualize urolithiasis in AUS have been found. This would support the use of this technique in patients with a high BMI despite clinical guides advising to perform CT as an initial diagnostic imaging test on this group of patients.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, especially Antonio Jesús Láinez Ramos-Bossini for providing us with the radiological images, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical concerns

This paper has been approved by the Research Research Ethics Committee of the Province of Granada (code 1235-N-20).

References

- Francisco Javier Ancizu FD-C. Cólico renal. [Internet]. [Last access: 29 March 2021]. Available at: https://docplayer.es/111525020-Colico-renal-francisco-javier-ancizu-fernando-diez-caballero.html

- Gary C Curhan, MD S, Mark D Aronson M, Glenn M Preminger M. Diagnóstico y manejo agudo de la sospecha de nefrolitiasis en adultos – UpToDate [Internet]. 2021 [Last access: 5 March 2021].

- Singh P, Enders FT, Vaughan LE, Bergstralh EJ, Knoedler JJ, Krambeck AE, et al. Stone Composition Among First-Time Symptomatic Kidney Stone Formers in the Community. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015; 90(10):1356–65.

- Sánchez-Carreras Aladrén F, Verdú Tartajo F, Herranz Amo F, Escribano Patiño G, María Díez Cordero J, Moncada Iribarren José Jara Rascón I, et al. Urgencias urológicas [Internet]; 2014 [Last access: 8 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.aeu.es/UserFiles/files/Urgencias_Urologicas.pdf

- Aller Rodríguez M, Álvarez Castelo L, Asensi Pernas A, Cabana Cortizas MT, Caeiro Castelao JM, Calvo Quintela L, et al. Abordaje práctico de la patología urológica [Internet]. María Sánchez J, Venancio M, Abal C, editors. EdikaMed, S.L; 2014 [Last access: 8 March 2021]. 277 p. Available at: www.cedro.org

- Brown J. Diagnostic and treatment patterns for renal colic in US emergency departments. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38(1):87–92.

- Susaeta R, Benavente D, Marchant F, Gana R. Diagnóstico y manejo de litiasis renales en adultos y niños. Rev Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2018;29(2):197–212.

- Fwu C-W, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Kirkali Z. Emergency department visits, use of imaging, and drugs for urolithiasis have increased in the United States. Kidney Int. 2013 ;83(3):479–86.

- Coursey CA, Casalino DD, Remer EM, Arellano RS, Bishoff JT, Dighe M, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® acute onset flank pain-suspicion of stone disease. Vol. 28, Ultrasound Quarterly. 2012.

- Mark L Zeidel M, W Charles O’Neill M. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of urinary tract obstruction and hydronephrosis – UpToDate [Internet]. 2021 [Last access: 5 March 2021].

- van der Molen AJ, Miclea RL, Geleijns J, Joemai RMS. A Survey of Radiation Doses in CT Urography Before and After Implementation of Iterative Reconstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 2015 [Last access: 29 March 2021];205(3):572–7.

- RadiologyInfo.org | Español [Internet]. [Last access: 29 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.radiologyinfo.org/sp/

- Smith D, Patel U. Ultrasonography vs computed tomography for stone size. BJU Int. 2017 Mar 1 [Last access: 7 March 2021];119(3):361–2. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bju.13735

- Arrabal Martín M, Barrero Candau R, Campoy Martínez P, Carnero Bueno J, Del Río Urenda S. Urolitiasis: proceso asistencial integrado [Internet]. Junta de A. 2012 [Last access: 12 March 2021]. 230 p. Available at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyfamilias/areas/calidad-investigacion-conocimiento/gestion-conocimiento/paginas/pai-urolitiasis.html

- Robledo Aburto ZA, Borja Aburto VH, Lira Romero JM, Arizmendi Urise E, Peña viveros R. Diagnóstico y tratamiento del cólico renoureteral en el servicio de urgencias. Durango 289-1A Colonia Roma; 2019 [Last access: 29 March 2021].

- Nicolau C, Salvador R, Artigas JM. Diagnostic management of renal colic. Radiología. 2015. 57(2):113–22.

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019 (Suppl 1):S31–4.

- F.Xavier P-S, D DMBS, Bouchard C, A R. The Practical Guide Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative. 2000 [Last access: 29 March 2021]. 94 p.

- Jung SI, Kim YJ, Park HS, Jeon HJ, Park HK, Paick SH, et al. Sensitivity of digital abdominal radiography for the detection of ureter stones by stone size and location. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34(6):879–82.

- Semins MJ, Shore AD, Makary MA, Magnuson T, Johns R, Matlaga BR. The Association of Increasing Body Mass Index and Kidney Stone Disease. J Urol. 2010;183(2):571–5.

- Ganesan V, De S, Greene D, Torricelli FCM, Monga M. Accuracy of ultrasonography for renal stone detection and size determination: is it good enough for management decisions? BJU Int. 2017;119(3):464–9.

- Rob S, Bryant T, Wilson I, Somani BK. Ultra-low-dose, low-dose, and standard-dose CT of the kidney, ureters, and bladder: is there a difference? Results from a systematic review of the literature. Vol. 72, Clinical Radiology. W.B. Saunders Ltd; 2017. p. 11–5.

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, Bengiamin RN, Camargo CA, Corbo J, et al. Ultrasonography versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(12):1100–10.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Pérez-Núñez J.J., Olea-Rodríguez P, Palacios-López R.M. Diagnóstico del cólico renal complicado mediante pruebas de imagen: un estudio retrospectivo observacional. AMU. 2021; 3(1):8-23