Antonio Sánchez-Merino 1; Miguel Ángel Huerta-Martínez 2; Alexandru Ovidiu Zabava 3

1 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

2 Departamento de Farmacología e Instituto de Neurociencias, Facultad de Medicina y Centro de Investigación Biomédica, Universidad de Granada (UGR)

3 Institut für Biologie, Karl-Franzens Universität Graz | Universidad de Granada (UGR)

Translated by:

Paula Trillo-Peña 4; Ana Castillo-González 4; Rubén García-Delgado 4; Virginia Sagarra-García 4; Antonio Jódar-González 4; María Rodríguez-Palomo 4; Olga Fenoll-Martínez 4

4 Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, University of Granada (UGR)

Introducción

La COVID-19 es un ejemplo de enfermedad infecciosa de nueva aparición con capacidad pandémica. Aunque ya hay numerosos estudios sobre esta enfermedad el foco actual está en relacionar la enfermedad con posibles secuelas a largo plazo, así como, con manifestaciones neurológicas. Por este motivo, el objetivo de nuestro trabajo es estudiar la relación entre la infección por el virus SARS-CoV-2 y el desarrollo de convulsiones de nueva aparición, es decir, en pacientes que previamente no habían sido diagnosticados con epilepsia.

Métodos

Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de artículos y preprints en las bases de datos MedLine, Scopus y Web of Science entre el 24 de febrero y el 7 de marzo del 2021. Los términos MeSH y palabras clave empleados a la hora de realizar la búsqueda fueron: (“SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“Seizures” OR “Status Epilepticus” OR “Electroencephalography” OR “EEG”) NOT (“Epilepsy”).

Resultados

Se incluyeron 21 estudios en la revisión sistemática tras realizar el cribado. Se estimó que aproximadamente el 2,9 % de pacientes con COVID-19 y con síntomas neurológicos tuvo un cuadro convulsivo de nueva aparición, y que un 0,67 % de los casos con COVID-19 cursó con convulsiones de nueva aparición. Los síntomas coexistentes más comunes entre estos pacientes fueron fiebre, vómitos, tos y malestar general. El tratamiento con antiepilépticos fue clave para la mejoría del estado de salud de los pacientes que desarrollaron convulsiones de nueva aparición.

Conclusión

Con los escasos datos disponibles, actualmente es imposible establecer una asociación directa entre la infección por SARS-CoV-2 y el desarrollo de convulsiones de nueva aparición. Tampoco se puede afirmar todavía el mecanismo fisiopatológico causante de las convulsiones. En cambio, se puede concluir que generalmente estas convulsiones se revierten exitosamente con tratamiento farmacológico antiepiléptico y los pacientes suelen evolucionar positivamente.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, secuelas neurológicas, convulsiones, status epilepticus.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, neurological sequelae, seizures, status epilepticus.

Introducción

Las enfermedades infecciosas constituyen un problema a nivel global, especialmente por la aparición de nuevos agentes infecciosos potencialmente peligrosos (1). El género de los betacoronavirus es un ejemplo de familia de enfermedades emergentes con capacidad pandémica (2): en 2002 el Síndrome Respiratorio Agudo Grave (SARS-CoV), en 2012 el coronavirus del Síndrome Respiratorio de Oriente Medio (MERS-CoV) (3,4), y en 2019 los primeros casos del SARS-CoV-2 (5,6). Este último virus fue declarado pandemia por la Organización Mundial de la Salud el 11 de marzo de 2020 (6).

Los artículos que analizaron las características clínicas del primer brote de SARS-CoV-2 reportaron una alta incidencia de síntomas bastante inespecíficos como fiebre, tos, dificultad respiratoria o diarrea (7-9), sin mención alguna respecto a manifestaciones neurológicas. Las primeras manifestaciones neurológicas se evaluaron por primera vez en Mao et al. 2020 (10), donde se estimó que aparecían en un 36% de pacientes con COVID-19. Los síntomas más comunes encontrados fueron mareos, dolor de cabeza, pérdida de gusto y pérdida de olfato. Además, en dicho artículo se reporta el primer caso de convulsiones asociadas a la enfermedad. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las revisiones posteriores reportan alteraciones neurológicas muy diversas (dolor de cabeza, mareos o alteración del nivel de conciencia), con una prevalencia mucho más baja en comparación con las complicaciones respiratorias (11,12). Debido a este motivo las manifestaciones neurológicas fueron reportadas más tarde.

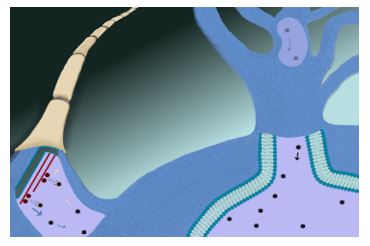

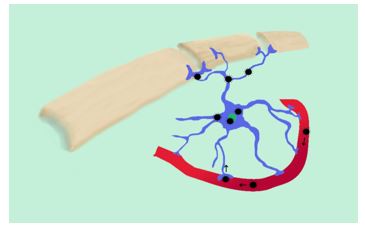

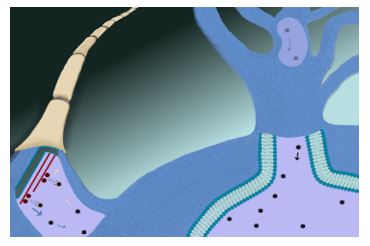

En cuanto a la fisiopatología, no se conoce con exactitud la ruta neuroinvasiva exacta del SARS-CoV-2. Se han sugerido principalmente dos rutas hipotéticas: la diseminación neural (figuras 1 y 2) a través del nervio olfatorio y la placa cribiforme, ruta que ya fue demostrada con anterioridad para el MERS-CoV y el SARS-CoV tanto en animales (13,14) como en humanos (15-17); y la diseminación hematógena (figura 3) a través de la circulación cerebral (18). Teniendo en cuenta estas posibles rutas, la invasión neuronal del SARS-CoV-2 se puede dar de una forma similar y estar relacionada con los síntomas neurológicos (11).

Figura 1. Representación simplificada de la maquinaria de transporte axonal. Se representa una neurona con cortes en la membrana del soma en parte del cono axónico a la izquierda, donde se muestra el hipotético transporte del virus a través del axón.

Figura 2. Diseminación neural. Se representa la exocitosis presináptica y endocitosis postsináptica del virus.

Figura 3. Presencia de coronavirus en astrocitos. Representación de un astrocito infectado y de la diseminación hematógena.

Aunque cada vez hay más artículos sobre secuelas neurológicas a largo plazo en pacientes con COVID-19, la evidencia no es concluyente y hacen falta más estudios al respecto para poder estimarla. Es por esto que en nuestro estudio se realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura actual sobre el tema con enfoque en una manifestación neurológica muy específica, las convulsiones de nueva aparición. Aunque los casos reportados de convulsiones por COVID-19 actualmente son pocos, no por su baja incidencia hay que olvidarlos pues poseen tratamiento efectivo y un reconocimiento temprano puede tener una gran repercusión clínica (19).

Por todo ello, el objetivo de esta revisión sistemática es estudiar la relación entre la infección por el virus SARS-CoV-2 y el desarrollo de convulsiones en pacientes que previamente no tenían epilepsia diagnosticada. También se estudiará la posible etiología de esta manifestación, su desenlace y posibles comorbilidades asociadas.

Métodos

En este trabajo se ha realizado una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica publicada en relación con la COVID-19 y las secuelas neurológicas que genera, específicamente las convulsiones en pacientes con COVID-19 que no hubiesen sido diagnosticados anteriormente con epilepsia. Para su elaboración se siguieron las directrices de la declaración PRISMA para la correcta elaboración de revisiones sistemáticas (20).

Estrategia de búsqueda

Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de artículos y preprints en las bases de datos MedLine, Scopus y Web of Science entre el 24 de febrero y el 7 de marzo del 2021. Los términos MeSH y palabras clave empleados a la hora de realizar la búsqueda para encontrar artículos que se centrasen en las convulsiones como secuela del COVID-19 fueron: (“SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“Seizures” OR “Status Epilepticus” OR “Electroencephalography” OR “EEG”) NOT (“Epilepsy”).

Gestión de los datos

Los artículos encontrados tras realizar la búsqueda en las diferentes bases de datos se importaron a Zotero, un gestor bibliográfico gratuito. Tras la eliminación de los duplicados, se procedió a la lectura del título y resumen de cada uno de ellos, eliminando los que no tuvieran que ver con el tema, los que no mencionan convulsiones en el contexto de pacientes con COVID-19 o los que únicamente hablasen de secuelas neurológicas en general. Una vez realizado este cribado, se procedió a la lectura completa de los artículos restantes para proceder a la selección de los artículos definitivos para realizar la revisión sistemática, teniéndose en cuenta los siguientes criterios de inclusión:

- Artículos publicados en inglés que fuesen estudios originales, estudios de cohortes, estudios de casos y controles o series de casos que tuvieran información sobre pacientes no diagnosticados de epilepsia que desarrollan convulsiones en el contexto de la COVID-19.

- Que tuviesen suficiente información sobre los pacientes, los síntomas neurológicos (especialmente convulsiones), las pruebas realizadas (tanto de imagen como de laboratorio), el tratamiento y la evolución de los pacientes.

- Que los pacientes estudiados tuvieran diagnóstico positivo en SARS-CoV-2 por cualquier procedimiento que lo permita (PCR, prueba serológica o test de antígenos).

En cuanto a los criterios de exclusión, se rechazaron:

- Revisiones sistemáticas o narrativas, meta-análisis o cartas al editor.

- Estudios que no tuviesen suficiente información sobre los pacientes o en los que la aportada no fuera relevante para la revisión.

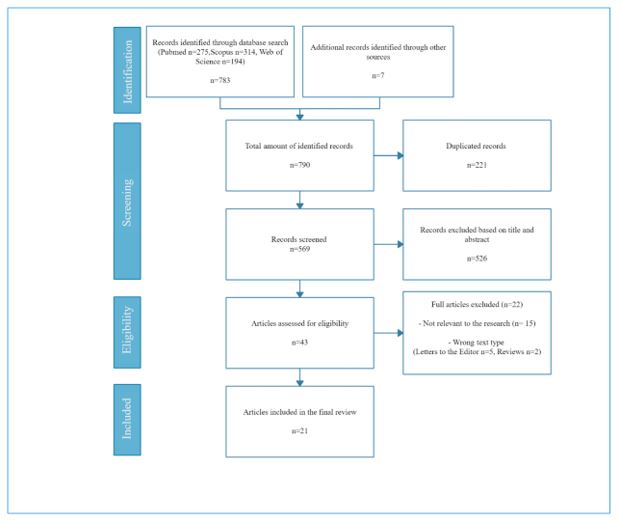

La evaluación de la inclusión o exclusión de cada uno de los artículos restantes fue realizada por dos de los tres revisores para evitar sesgos de selección, realización o de desgaste. Una vez realizada la elección de los artículos por cada uno de ellos, se compartieron los resultados y las discrepancias entre ambos se resolvieron dialogando. De este modo se seleccionaron los artículos para realizar la revisión. Además, los artículos seleccionados se cribaron para buscar otras referencias que tuviesen información original sobre el tema de estudio y que por cualquier motivo se hubiesen escapado a la búsqueda sistemática, a aquellas relevantes se les aplicaron los criterios de inclusión y exclusión para formar parte de la revisión. La figura 4 (diagrama de flujo PRISMA) muestra a modo de resumen todo lo descrito con anterioridad.

Figura 4. Diagrama de flujo de acuerdo con la guía PRISMA (20).

Por último, dos de los revisores realizaron una evaluación del sesgo de todos los estudios observacionales incluidos en la revisión usando una versión modificada de la escala de Newcastle-Ottawa (NOS) para obtener la calidad de los diferentes estudios. Las discrepancias entre ambos autores se resolvieron dialogando. Como la escala de Newcastle-Ottawa no es adecuada para valorar estudios de casos y controles, estos no fueron incluidos en la valoración del sesgo pues según el nivel de evidencia de la red JAMA (21) estos presentan el más alto.

Resultados

Del total de los 790 registros identificados, se incluyeron 21 estudios en la revisión sistemática tras el proceso descrito en el apartado anterior. Los artículos seleccionados se resumieron en la Tablas 1 a 3. En la Tabla 2 se incluyeron los valores obtenidos en la escala modificada de Newcastle-Ottawa (22), que se clasificaron como insatisfactorio (0-3 puntos), satisfactorio (4-5 puntos), bueno (6-7 puntos) y muy bueno (8-9 puntos). De este modo, una mayoría de cuatro artículos fueron considerados como satisfactorios, tres como buenos y uno como muy bueno. La calificación detallada de cada estudio se puede encontrar en el apéndice (Tabla 1).

En la Tabla 1 se resume la información de los estudios de casos clínicos (23-35). Entre los síntomas más frecuentes de los pacientes, se encuentra la fiebre, tos, vómitos y malestar general. En la mayoría de los estudios los pacientes tenían comorbilidades, salvo alguna excepción como el estudio de Fasano et al. (26), en el cual el paciente sin antecedentes previos desarrolla una convulsión con movimientos clónicos en el brazo derecho, o el estudio de Suhail Hussain (31), en la que el paciente sin apenas síntomas desarrolla cuatro episodios de convulsiones generalizadas tónico-clónicas. En cuanto al tratamiento cabe destacar la efectividad de los antiepilépticos ya que todos los pacientes fueron tratados con ellos. Excepto cuatro estudios en los que el paciente empeoró o incluso falleció (28,30), en el resto los pacientes dejaron de tener convulsiones y su estado de salud fue mejorando hasta que recibieron el alta.

Los estudios observacionales de cohortes se resumieron en las tablas 2 y 3 (36-42). Gracias a su tamaño de muestra se pudo aproximar mediante un análisis matemático cuán frecuente es la aparición de convulsiones en pacientes con COVID-19. De esta manera, se estimó que aproximadamente el 2,9% de pacientes con COVID-19 y con síntomas neurológicos tendrán un cuadro convulsivo de nueva aparición. Además, gracias a la tabla 3, se realizó el cálculo de la proporción total de pacientes con COVID-19 que desarrollarán convulsiones de nueva aparición. Se estimó que un 0,67% de los casos con COVID-19 va a cursar con convulsiones de nueva aparición. En la Tabla 2 se explica detalladamente el análisis matemático de los datos.

Discusión

En esta revisión sistemática se estimó que menos de uno de cada diez pacientes con COVID-19 y con síntomas neurológicos desarrolló convulsiones, y que de cada 10.000 pacientes con COVID-19, 67 desarrollaron un cuadro convulsivo de nueva aparición. Estos datos indican que, aunque las alteraciones neurológicas en pacientes con COVID-19 son una manifestación común (43), las convulsiones no lo son tanto. De hecho, se tratan de casos bastante paradójicos, representando una proporción relativamente baja (entre un 1 y un 26 %) con respecto a otras alteraciones neurológicas (36,38).

Algo que comparten la mayoría de los pacientes que desarrollan convulsiones de nueva aparición asociadas a la COVID-19 es un gran número de comorbilidades junto con un cuadro grave de COVID-19. Sin embargo, a pesar de su gravedad, las convulsiones generalmente se revierten exitosamente con tratamiento farmacológico antiepiléptico (44). Además, como se muestra en Hepburn et al., 2020 (33), los pacientes con signos clínicos de convulsiones o encefalopatía inexplicable pueden beneficiarse de la monitorización electroencefalográfica además de la terapia antiepiléptica empírica.

Entre las posibles hipótesis de aparición de las convulsiones; por un lado, se asocian a las características fisiopatológicas de cuadros severos de COVID-19 que cursan con encefalopatía hipóxica, eventos cardiovasculares y tormenta de citoquinas que podrían ser responsables de desencadenar estas convulsiones (45); por otro lado, la invasión del sistema nervioso por el virus podría ser la causa que desencadene estos síntomas, como apuntan algunos estudios en los que el virus ha sido detectado en líquido cefalorraquídeo de pacientes con COVID que posteriormente desarrollaron encefalitis (46). Por último, es posible que la aparición de convulsiones en pacientes con COVID-19 sea una mera coincidencia producto de la probabilidad. Esto tiene bastante sentido si consideramos la proporción extremadamente baja entre los casos con COVID-19 notificados con convulsiones y el número total de casos con COVID-19 notificados (47).

En cuanto a las fortalezas del estudio, cabe destacar el seguimiento de las directrices PRISMA a la hora de la elaboración de la revisión. También remarcar la búsqueda cuidadosa y exhaustiva de la información, la minuciosa interpretación de todos los estudios incluidos y la evaluación del sesgo a la hora de la inclusión y exclusión de los artículos. Además, se estudió la calidad de los estudios por medio de la Escala de Newcastle-Ottawa. En cuanto a las limitaciones, es posible que con la ecuación de búsqueda empleada y por el empleo de solo tres bases de datos se hayan podido ignorar artículos relevantes. El poco tiempo de seguimiento de los estudios observacionales podría ser otra limitación del estudio.

Conclusión

A pesar de que actualmente se conoce poco sobre las secuelas de la COVID-19, la revisión plantea varias perspectivas con algunas estimaciones sobre la incidencia de las convulsiones de nueva aparición en pacientes con COVID-19. Aproximadamente el 2,9% de pacientes con COVID-19 y con síntomas neurológicos tuvo un cuadro convulsivo de nueva aparición y del total de pacientes con COVID-19 un 0,67% desarrollaron convulsiones de nueva aparición. Sin embargo, con los escasos datos disponibles, actualmente es imposible establecer una asociación directa entre la infección por SARS-CoV-2 y el desarrollo de convulsiones de nueva aparición. Tampoco se puede afirmar todavía el mecanismo fisiopatológico causante de las convulsiones. Lo que sí se puede concluir es que las convulsiones generalmente se revierten exitosamente con tratamiento farmacológico antiepiléptico y los pacientes suelen evolucionar positivamente.

Declaraciones

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este trabajo agradecen la implicación de los coordinadores y docentes de los cursos «Producción y traducción de artículos biomédicos (III ed.)» y «Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)», así como al equipo de traducción al inglés de este artículo.

Conflictos de interés

Los autores de este trabajo declaran no presentar ningún conflicto de interés.

Referencias

- Gao GF. From «A»IV to «Z»IKV: Attacks from Emerging and Re-emerging Pathogens. Cell. 2018;172(6):1157-9.

- de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, Munster VJ. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(8):523-34.

- Anderson RM, Fraser C, Ghani AC, Donnelly CA, Riley S, Ferguson NM, et al. Epidemiology, transmission dynamics and control of SARS: the 2002-2003 epidemic. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1447):1091-105.

- Mackay IM, Arden KE. MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol J. 2015;12(1):222.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-33.

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – events as they happen [Internet]. [citado 14 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

- Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683.

- Fathi M, Vakili K, Sayehmiri F, Mohamadkhani A, Hajiesmaeili M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, et al. The prognostic value of comorbidity for the severity of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2): e0246190.

- Favas TT, Dev P, Chaurasia RN, Chakravarty K, Mishra R, Joshi D, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;41(12):3437-70.

- Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264-75.

- K L, C W-L, S P, J Z, Ak J, Lr R, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Causes Multiple Organ Damage and Lethal Disease in Mice Transgenic for Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4. J Infect Dis. 2015;213(5):712-22.

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Brison E, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;807:75-96.

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Dubeau P, Bourgouin A, Lajoie L, Dubé M, et al. Human Coronaviruses and Other Respiratory Viruses: Underestimated Opportunistic Pathogens of the Central Nervous System? Viruses. 2019;12(1).

- Veronese S, Sbarbati A. Chemosensory Systems in COVID-19: Evolution of Scientific Research. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12(5):813-24.

- Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(7):995-8.

- Vohora D, Jain S, Tripathi M, Potschka H. COVID-19 and seizures: Is there a link? Epilepsia. 2020;61(9):1840-53.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

- Instructions for Authors [Internet]. Chicago: American Medical Association (JAMA); 2021 [citado 14 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/pages/instructions-for-authors#SecReviews.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; c2021. [citado 14 de marzo de 2021] Disponible en: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- Chen W, Toprani S, Werbaneth K, Falco-Walter J. Status epilepticus and other EEG findings in patients with COVID-19: A case series. Seizure. 2020;81:198-200.

- Ashraf M, Sajed S. Seizures Related to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Case Series and Literature Review. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9378.

- Bhagat R, Kwiecinska B, Smith N, Peters M, Shafer C, Palade A, et al. New-Onset Seizure With Possible Limbic Encephalitis in a Patient With COVID-19 Infection: A Case Report and Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709620986302.

- Fasano A, Cavallieri F, Canali E, Valzania F. First motor seizure as presenting symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;41(7):1651-3.

- Haddad S, Tayyar R, Risch L, Churchill G, Fares E, Choe M, et al. Encephalopathy and seizure activity in a COVID-19 well controlled HIV patient. IDCases. 2020;21:e00814.

- Sohal S, Mansur M. COVID-19 Presenting with Seizures. IDCases. 2020;20:e00782.

- Hwang ST, Ballout AA, Mirza U, Sonti AN, Husain A, Kirsch C, et al. Acute Seizures Occurring in Association With SARS-CoV-2. Front Neurol. 2020;11:576329.

- Hamidi A, Sabayan B, Sorond F, Nemeth AJ, Borhani-Haghighi A. A Case of Covid-19 Respiratory Illness with Subsequent Seizure and Hemiparesis. Galen Med J. 2020;9:e1915.

- Hussain S, Vattoth S, Haroon KH, Muhammad A. A Case of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Presenting with Seizures Secondary to Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Case Rep Neurol. 2020;12(2):260-5.

- Khan Z, Singh S, Foster A, Mazo J, Graciano-Mireles G, Kikkeri V. A 30-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with seizures and leukoencephalopathy. Sage Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20977032.

- Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–8.

- Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-8.

- Filatov A, Sharma P, Hindi F, Espinosa PS. Neurological Complications of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Encephalopathy. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7352.

- Nalleballe K, Reddy Onteddu S, Sharma R, Dandu V, Brown A, Jasti M, et al. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations in COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:71-4.

- Waters BL, Michalak AJ, Brigham D, Thakur KT, Boehme A, Claassen J, et al. Incidence of Electrographic Seizures in Patients With COVID-19. Front Neurol. 2021;12:614719.

- Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, Sánchez-Larsen Á, Layos-Romero A, García-García J, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1060-70.

- Mahammedi A, Saba L, Vagal A, Leali M, Rossi A, Gaskill M, et al. Imaging of Neurologic Disease in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: An Italian Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E270-3.

- Kremer S, Lersy F, de Sèze J, Ferré J-C, Maamar A, Carsin-Nicol B, et al. Brain MRI Findings in Severe COVID-19: A Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E242-51.

- Pinna P, Grewal P, Hall JP, Tavarez T, Dafer RM, Garg R, et al. Neurological manifestations and COVID-19: Experiences from a tertiary care center at the Frontline. J Neurol Sci. 2020;415:116969.

- Radmard S, Epstein SE, Roeder HJ, Michalak AJ, Shapiro SD, Boehme A, et al. Inpatient Neurology Consultations During the Onset of the SARS-CoV-2 New York City Pandemic: A Single Center Case Series. Front Neurol. 2020;11:805.

- Solomon T. Neurological infection with SARS-CoV-2 — the story so far. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(2):65-6.

- Asadi-Pooya AA. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure. 2020;79:49-52.

- Nikbakht F, Mohammadkhanizadeh A, Mohammadi E. How does the COVID-19 cause seizure and epilepsy in patients? The potential mechanisms. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102535.

- Nwani PO, Nwosu MC, Nwosu MN. Epidemiology of Acute Symptomatic Seizures among Adult Medical Admissions. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2016;2016:4718372.

- Goleva SB, Lake AM, Torstenson ES, Haas KF, Davis LK. Epidemiology of Functional Seizures Among Adults Treated at a University Hospital. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027920.

New-onset Seizures Associated with COVID-19: A Systematic Review

Introduction

COVID-19 is an example of a newly emerging, infectious disease with pandemic potential. Although there are numerous studies on this disease, the main focus now is on relating COVID-19 with possible long-term sequelae, as well as neurological manifestations. The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development of new-onset seizures, that is, in patients who had not been previously diagnosed with epilepsy.

Methods

A systematic search of articles and preprints was performed in three databases (MedLine, Scopus and Web of Science) between February 24 and March 7, 2021. The MeSH terms and keywords used in the search were: (“SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“Seizures” OR “Status Epilepticus” OR “Electroencephalography” OR “EEG”) NOT (“Epilepsy”).

Results

Twenty-one studies were included 21 studies in the systematic review after screening. It was estimated that approximately 2.9 % of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms developed new-onset seizures and about 0.67% of the total number of COVID-19 patients developed new-onset seizures. The most common coexisting symptoms among these patients were fever, vomiting, cough and malaise. Antiepileptic treatment was key to the improvement of the health status of patients who developed new-onset seizures.

Conclusion

With the limited data available, it is currently impossible to establish a direct association between SARSCoV-2 infection and the development of new-onset seizures. The pathophysiologic mechanism causing the seizures cannot yet be determined either. However, it can be concluded that generally, these seizures are successfully reverted with antiepileptic treatment and patients usually respond favorably.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, neurological sequelae, seizures, status epilepticus.

Introduction

Infectious diseases are a global problem, especially due to the emergence of new potentially dangerous infectious agents (1). The betacoronavirus genus is an example of a family of emerging diseases with pandemic potential (2): severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) in 2002, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) in 2012 (3,4), and the first SARS-CoV-2 cases in 2019 (5,6). SARS-CoV-2 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.

Articles analyzing the clinical features of the first SARS-CoV-2 outbreak reported a high incidence of rather nonspecific symptoms such as fever, cough, respiratory distress or diarrhea (7-9), with no mention of neurological manifestations. Neurological manifestations were first evaluated by Mao et al. 2020(10), where they were estimated to appear in 36% of COVID-19 patients. The most common symptoms found were dizziness, headache, loss of taste and loss of smell. The first case of seizures associated with COVID-19 was also reported in this study. However, most later reviews reported diverse neurological alterations (headache, dizziness or altered level of consciousness), with a much lower prevalence compared to respiratory complications (11,12). For this reason, neurological manifestations were reported later.

Regarding pathophysiology, the neuroinvasive pathway of SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain. Mainly, two hypothetical pathways have been suggested: neural dissemination (Figures 1 and 2) through the olfactory nerve and the cribriform plate, a pathway previously demonstrated for MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV in animals (13,14) and humans (15-17); and hematogenous dissemination (Figure 3) through cerebral circulation (18). Considering these possible pathways, neural invasion of SARS-CoV-2 may occur in a similar manner and be related to neurological symptoms (11).

Figure 1. Simplified representation of the axonal transport machinery. On the left, a neuron is depicted with cuts in the soma membrane in some parts of the axonal growth cone. This represents the hypothetical axonal transport of the virus.

Figure 2. Neural dissemination. Presynaptic exocytosis and postsynaptic endocytosis of the virus are depicted.

Figure 3. Presence of Coronavirus in astrocytes. Representation of an infected astrocyte and hematogenous dissemination.

Although there is an increasing number of articles on long-term, neurological sequelae in patients with COVID-19, there is still not much evidence on this regard and more studies are still needed to estimate them. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the current literature on the topic, focusing on a very specific neurological manifestation: new-onset seizures. The reported cases of seizures caused by COVID-19 are few and the incidence is low. Still, they should not be dismissed, since they have an effective treatment and early detection could be of great clinical importance (19).

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to study the relationship between SARS-CoV-2infection and the development of new-onset seizures in patients who had not been previously diagnosed with epilepsy. The possible etiology of this manifestation, its outcome and potential associated comorbidities are also investigated.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature on COVID-19 and its neurological sequelae was performed. Special focus is placed on seizures in patients who had not been previously diagnosed with epilepsy. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews was followed as a guideline to develop this review (20).

Search strategy

A systematic search of articles and preprints was conducted in three databases (MedLine, Scopus and Web of Science) between February 24 and March 7, 2021. The MeSH terms and keywords used when searching for articles on seizures as a sequela of COVID-19were: (“SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“Seizures” OR “Status Epilepticus” OR “Electroencephalography” OR “EEG”) NOT (“Epilepsy”).

Data management

The articles found after searching the databases were imported to Zotero (a free reference manager). After eliminating duplicates, the title and abstract of the remaining articles were read, eliminating those that were not related to the topic. The articles that were not relevant to the topic, those that did not mention seizures in patients with COVID-19 and those that only focused on neurological sequelae in general were also dismissed. Once the articles were screened, the reading process began to select the definitive articles for this systematic review. The selection criteria were the following:

- Original studies, cohort studies, case and control studies or case series published in English that provided information about patients not diagnosed with epilepsy who developed seizures in the context of COVID-19.

- Articles that provided sufficient information about patients, neurological symptoms (especially seizures), tests performed (imaging and laboratory tests), treatments and patients’ progress.

- Articles where the patients had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by any diagnostic method (PCR, serological tests or antigen test).

The exclusion criteria were:

- Systematic or narrative reviews, meta-analyses or letters to the editor.

- Studies that did not provide enough information about patients or studies where the information provided was not relevant for this review.

The choice of including or excluding the remaining articles was made by two of the three authors to avoid selection, performance or attrition bias. Once the choice had been made, the results were shared and any discrepancies were solved through dialogue. The selected articles were screened for other references that could provide original information about the topic of the study that may have been accidentally overlooked during the systematic search. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the relevant references. Figure 4 (PRISMA flowchart) summarizes the process described above.

Figure 4. Flowchart following PRISMA guidelines (20).

Lastly, two of the authors performed a bias assessment of all the observational studies included in the review using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)to determine the quality of the studies. Discrepancies between the authors were solved through dialogue. As the NOS is not suitable for assessing case-control studies, these were excluded from the assessment because, according to the level of evidence of the JAMA network, these are the most biased (21).

Results

Of the 790 records identified, 21 studies were included in this systematic review, following the procedure described above. The selected articles are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Table 2 includes the values obtained on the modified NOS (22). The values were classified as unsatisfactory (0-3 points), satisfactory (4-5 points), good (6-7 points) and very good (8-9 points). Following these criteria, four articles were rated as satisfactory, three as good and one as very good. The detailed assessment of bias for each article according to the modified NOS can be found in the appendix (Table 1).

Table 1 summarizes the information obtained (23-35). Some of the most common symptoms among are fever, cough, vomiting and malaise. Most studies show that patients present comorbidities, although we found some exceptions. For example, in a study by Farsano et al. (26), a patient without previous history developed a seizure with clonic movements of the right arm. In another study by Suhail Hussain (31), a patient with hardly any symptoms experienced four episodes of generalized clonic-tonic seizures. Regarding the treatment, the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs is noteworthy. With the exception of four studies where patients worsened or even died (28, 30), studies showed that patients stopped having seizures and their health status improved until they were eventually discharged.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the cohort observational studies (36-42). Thanks to the sample size, it was possible to estimate the frequency of new-onset seizures in COVID-19 patients by mathematical analysis. Thus, it was estimated that approximately 2.9% of patients with neurological symptoms derived from COVID-19 will develop new-onset seizures. The total proportion of COVID-19 patients that will develop new-onset seizures was also estimated, as shown in Table 3. It was estimated that 0.67% of COVID-19 patients will suffer from new-onset seizures. Table 2 explains the mathematical analysis performed.

Discussion

This systematic review estimated that less than one in ten patients with COVID-19 and neurological symptoms developed seizures, and that out of every 10,000 COVID-19 patients, 67 developed new-onset seizures. These data indicate that although neurological alterations are common among COVID-19 patients (43), this is not the case with seizures. In fact, paradoxically, these cases represent a relatively low proportion (between 1% and 26%) in contrast to other neurological manifestations (36, 38).

Patients that develop new-onset seizures associated with COVID-19 usually share a great number of comorbidities and suffer from severe COVID-19 symptoms. However, despite the severity, most seizures revert successfully with antiepileptic drug treatment (44). In addition, as shown by Hepburn et al., 2020 (33), patients with clinical signs of seizures or unexplained encephalopathy can benefit from electroencephalographic monitoring in addition to empiric antiepileptic treatment.

There are different hypotheses for the appearance of these seizures. On one hand, they might be associated with the pathophysiologic characteristics of severe cases of COVID-19. These cases present hypoxic encephalopathy, cardiovascular events and hypercytokinemia, which might be responsible for triggering these seizures (45). On the other hand, seizures might be caused by invasion of the nervous system by the virus, as suggested in different studies in which was detected in the CSF of COVID-19 patients that subsequently developed encephalitis (46). Lastly, the appearance of seizures in COVID-19 patients might be nothing but a mere coincidence and a matter of chance. This is not surprising considering the extremely low ratio of reported COVID-19 cases with seizures and the total amount of reported COVID-19 cases (47).

Regarding the strengths of this study, it is important to point out the adherence to the PRISMA system when elaborating this review. The exhaustive and comprehensive search carried out, the meticulous interpretation of all the studies included, as well as the assessment of potential bias are also worth highlighting. Moreover, the quality of the studies was determined using the NOS. Regarding the limitations of this study, it is possible that the search equation used and the use of only three databases and may have led to relevant studies being overlooked. The short follow-up time of observational studies may be another possible limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Although little is known about the sequelae of COVID-19, this review presents different perspectives and estimates on the incidence rates of new-onset seizures in COVID-19 patients. About 2.9 % of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms developed new-onset seizures and about 0.67% of the total number of COVID-19 patients developed new-onset seizures. However, with the limited data available, it is currently impossible to establish a direct association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development of new-onset seizures. The pathophysiologic mechanism behind the seizures cannot yet be established, but it can be concluded that antiepileptic drug treatment can successfully revert the seizures and that patients usually make good progress.

Statements

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the involvement of the coordinating and teaching staff of the “Producción y traducción de artículos científicos biomédicos (III ed.)” and the “Traducción inversa de artículos científicos biomédicos (español-inglés)” courses, as well as the English translation team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this paper declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao GF. From «A»IV to «Z»IKV: Attacks from Emerging and Re-emerging Pathogens. Cell. 2018;172(6):1157-9.

- de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, Munster VJ. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(8):523-34.

- Anderson RM, Fraser C, Ghani AC, Donnelly CA, Riley S, Ferguson NM, et al. Epidemiology, transmission dynamics and control of SARS: the 2002-2003 epidemic. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1447):1091-105.

- Mackay IM, Arden KE. MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol J. 2015;12(1):222.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-33.

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – events as they happen [Internet]. [citado 14 de marzo de 2021]. Disponibleen: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

- Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683.

- Fathi M, Vakili K, Sayehmiri F, Mohamadkhani A, Hajiesmaeili M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, et al. The prognostic value of comorbidity for the severity of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2): e0246190.

- Favas TT, Dev P, Chaurasia RN, Chakravarty K, Mishra R, Joshi D, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions. NeurolSci Off J Ital NeurolSoc Ital SocClinNeurophysiol. 2020;41(12):3437-70.

- Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264-75.

- K L, C W-L, S P, J Z, Ak J, Lr R, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Causes Multiple Organ Damage and Lethal Disease in Mice Transgenic for Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4. J Infect Dis. 2015;213(5):712-22.

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Brison E, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. AdvExp Med Biol. 2014;807:75-96.

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Dubeau P, Bourgouin A, Lajoie L, Dubé M, et al. Human Coronaviruses and Other Respiratory Viruses: Underestimated Opportunistic Pathogens of the Central Nervous System? Viruses. 2019;12(1).

- Veronese S, Sbarbati A. Chemosensory Systems in COVID-19: Evolution of Scientific Research. ACS ChemNeurosci. 2021;12(5):813-24.

- Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS ChemNeurosci. 2020;11(7):995-8.

- Vohora D, Jain S, Tripathi M, Potschka H. COVID-19 and seizures: Is there a link? Epilepsia. 2020;61(9):1840-53.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

- Instructions for Authors [Internet]. Chicago: American Medical Association (JAMA); 2021 [citado 14 de marzo de 2021]. Disponibleen https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/pages/instructions-for-authors#SecReviews.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; c2021. [citado 14 de marzo de 2021] Disponibleen: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- Chen W, Toprani S, Werbaneth K, Falco-Walter J. Status epilepticus and other EEG findings in patients with COVID-19: A case series. Seizure. 2020;81:198-200.

- Ashraf M, Sajed S. Seizures Related to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Case Series and Literature Review. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9378.

- Bhagat R, Kwiecinska B, Smith N, Peters M, Shafer C, Palade A, et al. New-Onset Seizure With Possible Limbic Encephalitis in a Patient With COVID-19 Infection: A Case Report and Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709620986302.

- Fasano A, Cavallieri F, Canali E, Valzania F. First motor seizure as presenting symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection. NeurolSci Off J Ital NeurolSoc Ital SocClinNeurophysiol. 2020;41(7):1651-3.

- Haddad S, Tayyar R, Risch L, Churchill G, Fares E, Choe M, et al. Encephalopathy and seizure activity in a COVID-19 well controlled HIV patient. IDCases. 2020;21:e00814.

- Sohal S, Mansur M. COVID-19 Presenting with Seizures. IDCases. 2020;20:e00782.

- Hwang ST, Ballout AA, Mirza U, Sonti AN, Husain A, Kirsch C, et al. Acute Seizures Occurring in Association With SARS-CoV-2. Front Neurol. 2020;11:576329.

- Hamidi A, Sabayan B, Sorond F, Nemeth AJ, Borhani-Haghighi A. A Case of Covid-19 Respiratory Illness with Subsequent Seizure and Hemiparesis. Galen Med J. 2020;9:e1915.

- Hussain S, Vattoth S, Haroon KH, Muhammad A. A Case of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Presenting with Seizures Secondary to Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Case Rep Neurol. 2020;12(2):260-5.

- Khan Z, Singh S, Foster A, Mazo J, Graciano-Mireles G, Kikkeri V. A 30-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with seizures and leukoencephalopathy. Sage Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20977032.

- Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–8.

- Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-8.

- Filatov A, Sharma P, Hindi F, Espinosa PS. Neurological Complications of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Encephalopathy. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7352.

- Nalleballe K, Reddy Onteddu S, Sharma R, Dandu V, Brown A, Jasti M, et al. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations in COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:71-4.

- Waters BL, Michalak AJ, Brigham D, Thakur KT, Boehme A, Claassen J, et al. Incidence of Electrographic Seizures in Patients With COVID-19. Front Neurol. 2021;12:614719.

- Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, Sánchez-Larsen Á, Layos-Romero A, García-García J, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1060-70.

- Mahammedi A, Saba L, Vagal A, Leali M, Rossi A, Gaskill M, et al. Imaging of Neurologic Disease in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: An Italian Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E270-3.

- Kremer S, Lersy F, de Sèze J, Ferré J-C, Maamar A, Carsin-Nicol B, et al. Brain MRI Findings in Severe COVID-19: A Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E242-51.

- Pinna P, Grewal P, Hall JP, Tavarez T, Dafer RM, Garg R, et al. Neurological manifestations and COVID-19: Experiences from a tertiary care center at the Frontline. J Neurol Sci. 2020;415:116969.

- Radmard S, Epstein SE, Roeder HJ, Michalak AJ, Shapiro SD, Boehme A, et al. Inpatient Neurology Consultations During the Onset of the SARS-CoV-2 New York City Pandemic: A Single Center Case Series. Front Neurol. 2020;11:805.

- Solomon T. Neurological infection with SARS-CoV-2 — the story so far. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(2):65-6.

- Asadi-Pooya AA. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure. 2020;79:49-52.

- Nikbakht F, Mohammadkhanizadeh A, Mohammadi E. How does the COVID-19 cause seizure and epilepsy in patients? The potential mechanisms. MultSclerRelatDisord. 2020;46:102535.

- Nwani PO, Nwosu MC, Nwosu MN. Epidemiology of Acute Symptomatic Seizures among Adult Medical Admissions. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2016;2016:4718372.

- Goleva SB, Lake AM, Torstenson ES, Haas KF, Davis LK. Epidemiology of Functional Seizures Among Adults Treated at a University Hospital. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027920.

AMU 2021. Volumen 3, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

14/03/2021 04/04/2021 31/05/2021

Cita el artículo: Sánchez-Merino A, Huerta-Martínez M. A., Zabava A. O. Convulsiones de nueva aparición asociadas con COVID-19: una revisión sistemática. AMU. 2021; 3(1):52-79