José Mateos-Granados ¹ , Carmen María López-Pérez ¹ , Ana Elena Lizana-Serrano ¹ , Álvaro Díaz Gómez ¹ , Alejandra Díaz-García ¹ , Raquel Moya-Barquero ¹

1 Estudiante del Grado en Medicina de la Universidad de Granada (UGR)

TRANSLATED BY:

Paola Rodríguez-González ² , José Luis Castillo-del-Águila ² , Irene Torres-Martínez ² , Ana García-Canteli ² , María Ruiz- Escrivá ² , Nuria Vadillo-Ucea ²

2 Student of the BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (UGR)

TRADUCCIÓN ÁRABE:

Abdulfattah Shaaba Akash-Akash ² Laura Maldonado-García ² , Leila El-Hachimi ² Abdelghani Sánchez-Sánchez ² , Fadila Oukk

2طلبة الترجمة التحريرية والشفوية في جامعة غرناطة

Resumen

El amianto o asbesto ha constituido un foco de preocupación en el campo de la salud desde que se descubrieron los primeros casos de enfermedades cancerígenas. Encontrándose en la mayoría de edificios, ya fuera como aislamiento o como parte de los tejados, entre otros usos, el asbesto ha sometido a la población durante años a su efecto nocivo. Estudiados desde entonces, los efectos adversos del amianto sobre el sistema respiratorio están ampliamente aceptados en el círculo científico. Sin embargo, las consecuencias en otros sistemas no están delimitadas tan claramente. En esta revisión tratamos de captar toda la información publicada y estudiada sobre la relación del amianto y el cáncer gastrointestinal (GI). Para ello, abordamos por separado cada parte del aparato digestivo en la cual se han estudiado las posibles evidencias, así como las generalidades que se encuentran en la literatura científica sobre dicha relación.

Palabras clave: amianto, cáncer, aparato digestivo.

Keywords: asbestos, cancer, digestive system.

1.INTRODUCCIÓN

El amianto, también llamado asbesto,

es un material clasificado como mineral natural de silicato fibroso que se

dispone en fibras. Tiene muchas propiedades físico-químicas, entre las que

destacan su flexibilidad y su resistencia a altas temperaturas y exposición a

químicos, las cuales lo han llevado a ser utilizado en construcción y en el

aislamiento de casas, escuelas y todo tipo de edificios. Existen distintas

variedades de amianto divididas en anfíboles y asbesto serpentina. Los

anfíboles son fibras rectas y entre ellos podemos destacar sobre todo la

crocidolita o amianto azul; y otros como la amosita, la antofilita o la

tremolita. El asbesto serpentina, crisotilo o asbesto blanco está formado por

fibras curvadas y constituye el 95% del amianto utilizado industrialmente.

El comienzo de su utilización en

industria se remonta a 1850. Ya a mitad del siglo siguiente, existían

evidencias de la relación entre la exposición a este material y su efecto

nefasto sobre la salud. A día de hoy, se siguen encontrando casos de enfermos

por esta razón pese a haberse prohibido su uso en aproximadamente 50 países

(1). A pesar de las continuas y repetidas advertencias sobre la toxicidad y la

carcinogenicidad de los materiales que contienen asbesto, un gran número de

personas de todas las edades, incluidos niños pequeños, están potencialmente

expuestos a estos (2). Asimismo, se ha demostrado el efecto de la exposición a

dichas fibras en pulmón provocando mesotelioma pleural, fibrosis pulmonar y

carcinoma broncogénico, entre otras enfermedades.

2. MECANISMOS DE ACCIÓN Y VÍAS DE EXPOSICIÓN

No se conocen bien los mecanismos por

los que la exposición al asbesto puede influir en la aparición del cáncer, pero

se sospecha que puede deberse al efecto inflamatorio causado por la presencia persistente

de sus fibras sobre los tejidos. También que, propiedades del mismo como la

longitud y diámetro de la fibra, su superficie y su durabilidad, influyen. El

menor de los diámetro es el de la crocidolita, y se considera el más dañino.

En la actualidad se está estudiando

la posibilidad de que el amianto produzca una u otra patología dependiendo de

la vía de acceso al organismo que utilice. De esta manera, al ser inhalado,

produce patología pulmonar; mientras que, al ser ingeridas sus fibras, puede provocar

cáncer GI. La ruta de exposición más probablemente implicada en los trastornos

GI es la ingesta de agua potable contaminada debido a la gran cantidad de

edificios provistos de tuberías de cemento reforzadas con amianto (3) o a la

contaminación natural.

3. AMIANTO E INGESTA DE AGUA

El asbesto ha sido clasificado como

un agente carcinogénico que puede inducir, en el tracto GI, alteraciones

histológicas y efectos negativos a nivel molecular en humanos. Por otro lado,

se ha observado que el nivel de fibras de amianto en el agua está en torno a 7

millones de fibras por litro, y dicha contaminación es mayor en el agua de la

superficie que en el agua de pozo. Dichas fibras provienen principalmente del

deterioro o la descomposición de los materiales que contienen amianto, como

aguas residuales de la minería y otras industrias, tuberías de amianto y

tanques de agua todavía presentes en los sistemas de suministro de la misma

(4,5).

Aún no se ha establecido un valor de

referencia para el amianto (6) en el agua potable, y tampoco han sido fijados

límites restrictivos en la concentración de fibras presentes en el agua ya que

no se conoce el umbral del riesgo carcinogénico a nivel del tracto GI. Hay que

tener en cuenta también que la cantidad variable de los factores de confusión

se deriva principalmente de la difícil cuantificación de la cantidad individual

de fibras ingeridas (7).

Asimismo, es importante saber que el

efecto del amianto ingerido es diferente según el grupo de edad. Es un aspecto

aún sin explorar, pero puede ser de gran importancia ya que los niños son más

susceptibles que los adultos a los peligros de origen ambiental, pues tienen

una mayor esperanza de vida, y vivir en un área geográfica contaminada de forma

continua se traduce en una exposición más prolongada al amianto ingerido por

vía oral. Además, la cantidad total de agua que beben los niños es

aproximadamente siete veces más alta que la ingerida por los adultos.

Por otro lado, existe la posibilidad

de transferir al feto las fibras de amianto ingeridas por la madre (8). Este

hallazgo ha sido comprobado tras la detección, en bebés nacidos muertos

autopsiados, de fibras de amianto a nivel de la placenta, pulmón, músculo e

hígado. En dicho estudio se observó que el recuento de fibras fue mayor en el hígado,

así como que la longitud media de las fibras detectadas era comparable a las

fibras derivadas del sistema de tuberías y cisternas previamente mencionado.

Por todo ello, sería importante

establecer un nivel máximo aceptable de amianto en el agua potable en los

diversos países, lo que permitiría justificar una revisión de las normas

existentes, con el fin de evitar un riesgo aumentado de desarrollo de cánceres.

4. NEOPLASIAS PERITONEALES Y OTRAS POSIBLES AFECCIONES

La literatura científica parece

apoyar una fuerte asociación entre la exposición al amianto y las neoplasias

peritoneales, cuyo tratamiento es poco efectivo (9). Se vio que el riesgo era

menos severo en trabajadores expuestos a crisotilo que en los expuestos a una

mezcla de crisotilo y crocidolita, por lo que el tipo de fibras tenía relación

con la localización y posiblemente la severidad de las distintas neoplasias,

suponiendo la exposición al anfíbol una mayor amenaza para el desarrollo de

tumores peritoneales (10). Este riesgo es proporcional a la cantidad y

exposición de la sustancia.

El tamaño de las fibras también

parece ser un factor importante en el efecto cancerígeno del amianto. En un

estudio en el que se analizaron 168 casos de mesotelioma, la mayoría de las

fibras no superaban las 5 micras de longitud. No existe un mecanismo conocido

para el contacto directo del amianto con el peritoneo. Es posible que la

activación de cascadas de señales iniciadas en el pulmón sean las responsables

de producir la enfermedad en el peritoneo. Específicamente, cascadas en las que

está implicado el TGF-beta.

Asimismo, se ha demostrado que el

hierro influye en el potencial cancerígeno de la crocidolita debido a un

aumento del estrés oxidativo en una situación de exceso de este elemento. De

hecho, se piensa que el potencial mutagénico del amianto es debido, al menos

parcialmente, a los radicales libres, ya que se ha visto que ese efecto

mutagénico se ve reducido por los antioxidantes (11). Los efectos adversos de

este mineral incluyen además cáncer de ovario, gastrointestinal, tumores

cerebrales, alteraciones sanguíneas o fibrosis peritoneal. Por todo ello, es

evidente que las propiedades adversas del amianto no están confinadas al

aparato respiratorio.

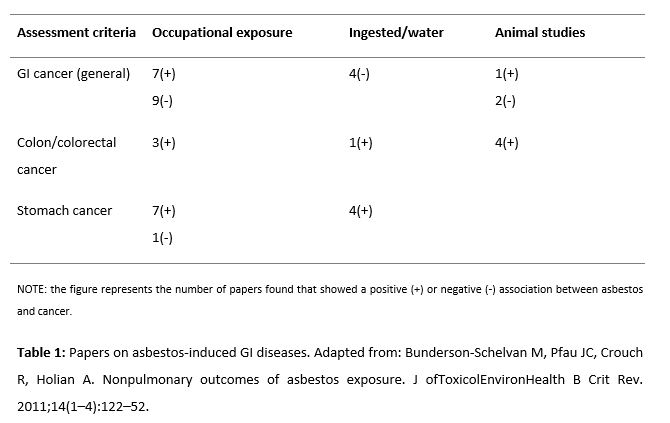

Finalmente, considerando más concretamente el aparato digestivo, cabría destacar que, a pesar de que el tracto GI tiene una gran capacidad para transportar y eliminar las fibras rápidamente, la relación entre el transporte y la retención de las fibras de asbesto en el desarrollo de los cánceres GI es una consideración importante que no se ha investigado bien (12). Según las publicaciones revisadas, la exposición a asbesto ha sido sobre todo relacionada con cáncer de estómago (13-17), esófago (18) y colon (13,19), aunque aún sin evidencias significativas que demuestren la relación causal (20). También hay asociación con esófago e intestino delgado. En la Tabla 1 se puede observar que en la literatura científica se ha encontrado numerosa evidencia a favor de esta asociación (21).

| Criterios de valoración | Exposición en el ámbito laboral | Ingeridas/agua | Estudios en animales |

| Cáncer GI (general) | 7(+) 9(-) |

4(-) | 1(+) 2(-) |

| Cáncer de colon/colorrectal |

3(+) | 1(+) | 4(+) |

| Cáncer de estómago |

7(+) 1(-) |

4 (+) |

TABLA 1. Publicaciones sobre las enfermedades gastrointestinales inducidas por el amianto. El número indica cuántos artículos fueron encontrados con una asociación positiva (+) o negativa (-) entre el amianto y la enfermedad.

Adaptado de Bunderson-Schelvan M, Pfau JC, Crouch R, Holian A. Nonpulmonary outcomes of asbestos exposure. J of Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(1–4):122–52.

5. CÁNCER DE ESÓFAGO

En lo que respecta a la relación

entre la exposición laboral al asbesto y el desarrollo de cáncer de esófago,

este aspecto continúa siendo controvertido al ser un cáncer menos frecuente. Es

importante considerar que el cáncer de esófago cuenta con numerosos factores de

riesgo presentes con frecuencia en la población general, tales como el tabaco,

el consumo de alcohol o el reflujo gastroesofágico. El no considerar la

presencia de estos factores puede restar validez a las conclusiones extraídas

de las diferentes investigaciones realizadas, como así ocurre en algunas de las

llevadas a cabo (22).

Otro de los aspectos que plantean

dudas en este campo es, si de existir dicha relación, ésta es dosis-dependiente

o no. Para ello, el estudio más reciente realizado planteaba la división de los

sujetos en estudio en cuatro grupos, en función de su grado de exposición

laboral al amianto, concluyendo que se trataba de una relación dosis

dependiente (23).

Considerando todo lo anteriormente

expuesto, las evidencias actuales apuntan en la dirección de que la asociación

entre la exposición al asbesto y el desarrollo posterior de cáncer de esófago

es positiva, aunque en la mayoría de los casos la evidencia estadística no es

lo suficientemente sólida para poder extraer conclusiones definitivas (22,23).

Por otro lado, los resultados tampoco

son concluyentes en cuanto al subtipo de cáncer de esófago más implicado en

este aspecto. Así, hay estudios que únicamente han encontrado evidencias de la

estudiada relación con el adenocarcinoma, pero no con el carcinoma de células

escamosas (que es el subtipo más frecuente) (24). Sin embargo, otras

investigaciones llevadas a cabo carecen de datos para poder aportar mayor

claridad en este aspecto (22,23).

Por todo ello, los estudios hasta

ahora realizados ponen de manifiesto la necesidad de continuar con la

investigación en este campo para así poder concluir de forma más sólida sobre

la existencia, o no, de esta relación.

6. CÁNCER DE ESTÓMAGO

La relación entre la exposición a

asbesto y el cáncer gástrico ha sido estudiada sin resultados concluyentes

debido al bajo número de casos. Un meta-análisis del 2015 (25) determinó la

incidencia y mortalidad del cáncer de estómago entre trabajadores expuestos al

amianto mediante una revisión sistemática.

Los estudios que se consideraron

fueron de cohortes humanas en los que había evidencia clara de exposición a

asbesto (principalmente por empleo en industria textil, cemento, minería y

astilleros), y aportaban un índice estandarizado de incidencia o mortalidad

(como subtipo de incidencia, debido al corto periodo de supervivencia). Se

excluyeron, por otra parte, estudios en animales, con datos duplicados o en los

que la exposición ocupacional era conjunta a otros factores, no solo asbesto.

De las cohortes seleccionadas se recogió el tamaño, tipo de asbesto al que se

exponían, periodo de empleo, tiempo de seguimiento, número de cánceres

observados y modelo de aleatorización. Se obtuvieron 40 cohortes de 32 estudios

independientes en los cuales se observó que: cinco trataban sobre la incidencia

del cáncer gástrico (nuevos casos diagnosticados), el resto sobre mortalidad;

la mayoría estaban hechos en Europa, cinco en Asia, tres en América y cuatro en

Oceanía; y trece estudios tenían solo cohortes masculinas y cinco solo

femeninas.

El análisis del trabajo evidenció un

significante aumento del riesgo de cáncer gástrico en las cohortes expuestas

únicamente a crocidolita y asbesto mixto; y que la ratio había aumentado en las

de Europa y Oceanía. En cuanto a la heterogeneidad propia del estudio, se

determinó que dependía del género de la cohorte, no así del tipo de asbesto,

región, industria, tamaño de muestra o tipo de resultado.

La revisión considerada concluye que

los trabajadores expuestos a asbesto tienen 1,19 veces más posibilidades de

sufrir cáncer gástrico con respecto al resto de la población. No obstante, la

discusión señala dos aspectos de interés:

El riesgo está más definido en los hombres, en los que otros factores del estilo de vida tales como el alcohol y el tabaco, que pudieran influir en el resultado, son más frecuentes que en las mujeres (26). Los estudios señalan que el tabaco es el factor más dañino y determinante de la aparición del cáncer gástrico mientras que el alcohol lo es de su progresión.

La mayoría de cohortes estaban formadas por mineros. Consecuentemente, puede haber cierto sesgo aquí, habiendo estudios (27) que señalan el aumento de riesgo de cáncer en mineros y molineros. Finalmente, también hay indicios que lo relacionan con el polvo del carbón (28).

7. CÁNCER COLORRECTAL

Al igual que el contacto con el

amianto puede ser causante de cáncer gástrico, es lógico plantearse si éste

puede ser un causante de cáncer en las partes más distales del tracto GI. Así,

se plantea a continuación una exposición de la evidencia en la literatura

científica de la relación entre la exposición al asbesto y el cáncer

colorrectal (CCR).

Se observa en estudios experimentales

ya desde 1980 que ratones que ingieren amianto en altas cantidades acaban

desarrollando CCR (29). Esta, como ya se ha visto, es una vía de exposición al

asbesto en humanos, aunque no a tan alta concentración como en este

experimento. Es por ello que esta evidencia es insuficiente, haciéndose

necesario un estudio pormenorizado en humanos.

Existen numerosos estudios de

cohortes que analizan esta relación, atendiendo a diversos factores como el

tipo de exposición y la duración de la misma. Un estudio realizado en

Normandía, Francia, encontró un gran aumento en el número de casos esperados de

CCR en varones trabajadores de una fábrica con larga historia de exposición, de

más de 25 años de duración (30).

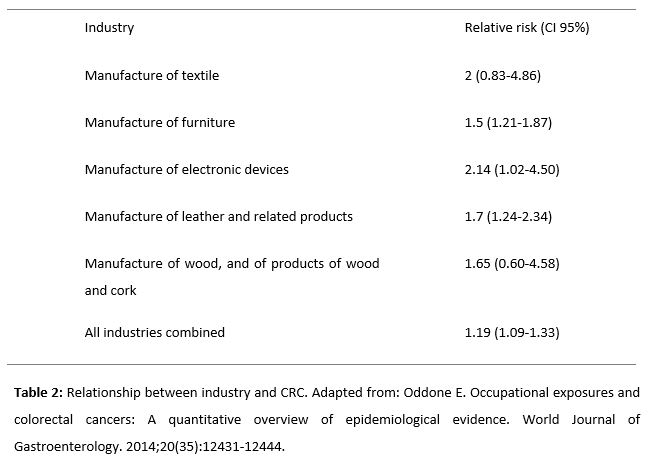

No obstante, aun hablando de exposiciones ocupacionales, el tipo de industria en la que se trabaje es importante para cuantificar el aumento del riesgo. Así, analizando los numerosos estudios de cohortes disponibles en la literatura, se observa que las industrias más proclives a aumentar el riesgo de sufrir CCR son la industria textil y la manufactura de productos electrónicos, como se puede observar en la Tabla 2 (31).

| Rama industrial | Riesgo relativo (IC 95%) |

| Textil | 2 (0,83-4,86) |

| Fabricación de muebles |

1,5 (1,21-1,87) |

| Fabricación de productos electrónicos |

2,14 (1,02-4,50) |

| Fabricación de cuero y relacionados |

1,7 (1,24-2,34) |

| Industria maderera |

1,65 (0,60-4,58) |

| Todas las ramas combinadas |

1,19 (1,09-1,33) |

Tabla 2. Relación entre industria e incidencia de CCR. Adaptado de Oddone E. Occupational exposures and colorectal cancers: A quantitative overview of epidemiological evidence. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(35):12431-12444.

En cuanto a otros tipos de

exposición, como la exposición doméstica por la presencia de aislante de

amianto en el hogar, se hace patente un aumento del riesgo, pero no

significativo (32), por lo que sería necesario la realización de más estudios

que analizasen si existe una relación significativa entre esta exposición y el

CCR, como sí se ha demostrado en otros tipos de cáncer tales como el

mesotelioma o el cáncer de pulmón (33, 34).

Por lo tanto, respecto a la

asociación entre exposición al asbesto y el CCR, podemos concluir que, aunque

existe evidencia de relación entre ambos, ésta no es tan fuerte como en otros

tipos de cáncer, por lo que serían necesarios más estudios. Además, es

necesario tener en cuenta el tipo de exposición analizada, ya que se pueden

sospechar diferencias dependiendo de si se trata de una exposición laboral o

doméstica.

8. CONCLUSIONES

El amianto es un mineral cuyas capacidades carcinogénicas son bien conocidas en el aparato respiratorio. No obstante, no existe evidencia suficiente que permita afirmar con seguridad que pueda ser responsable de tumores en otras partes del organismo. Esto se aplica también a los tumores del tracto GI.

Existe evidencia, aunque insuficiente, de relación entre la exposición a asbesto y la producción de tumores de esófago, aunque se hacen necesarios más estudios, especialmente aquellos que controlen la presencia de factores de confusión, como otros carcinógenos conocidos.

Igualmente, existe evidencia que relaciona el cáncer de estómago y la exposición laboral a amianto, pero sigue sin ser una evidencia significativa.

Distintos tipos de exposición al amianto, ya sea exposición laboral, en el agua potable o como aislante en el hogar, han sido relacionados con el cáncer colorrectal, pero, al igual que el resto de tumores observados en el trabajo, requeriría mayor número de casos para poder constituir una evidencia significativa.

En general, la relación del amianto y los tumores gastrointestinales, aunque patente, requiere de mayor evidencia, tanto experimental como observacional. El abandono de su uso, sin embargo, dificulta la recopilación de evidencia observacional.

No obstante, es necesario confirmar esta relación por la presencia de amianto en el agua potable, cuyos niveles no se controlan tan estrechamente como se debería si se confirmaran los efectos carcinogénicos en el tracto GI.

9. CONFLICTOS DE INTERÉS

Los autores del presente artículo

declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés que pudiera sesgar los resultados

o las conclusiones de esta revisión.

10. REFERENCIAS

- Kim SJ, Williams D, Cheresh P, Kamp DW. Asbestos-Induced Gastrointestinal Cancer: An Update. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2013 Oct;3(3). pii: 135. Epub 2013 Sep 10. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000135

- Kjaerheim K, Ulvestad B, Martinsen JI, Andersen A. Cancer of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Exposure to Asbestos in Drinking Water among Lighthouse Keepers (Norway). Cancer Causes Control. 2005; 16:593–598. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-7844-1

- Ramazzini C. Asbestos is Still with Us: Repeat Call for a Universal Ban. Am J Ind Med. 2011; 54:168–173.doi: 10.1002/ajim.20892

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Toxological Profile for Asbestos. Agency Toxic Subst Dis Regist. 2001;(September):327.

- IARC. Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012; 100(PtC):11–465.

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality 4th ed., WHO, Geneva, p. 340. World Heal Organ. 2011;

- Kanarek MS. Epidemiological Studies on Ingested Mineral Fibres: Gastric and Other Cancers. IARC Sci Publ. 1989;90:428–437. PMID: 2744839

- Haque AK, Ali I, Vrazel DM et al. Chrysotile Asbestos Fibers Detected in The Newborn Pups Following Gavage Feeding of Pregnant Mice. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2001;62(1):23–31. PMID: 11205533

- Hesdorffer ME, Chabot J, DeRosa C, Taub R. Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:180–190. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0072-2

- McConnell EE, Shefner AM, Rust JH, Moore JA. Chronic Effects of Dietary Exposure to Amosite and Chrysotile Asbestos in Syrian Golden Hamsters. Environ Health Perspect. 1983;53:11–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.835311

- Kohyama N, Suzuki Y. Analysis of Asbestos Fibers In Lung Parenchyma, Pleural Plaques, and Mesothelioma Tissues of North American Insulation Workers. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;643:27–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb24442.x

- Bunderson-Schelvan M, Pfau JC, Crouch R, Holian A. Nonpulmonary Outcomes of Asbestos Exposure. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011; 14:122–152. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556048

- Kinugawa K, Ueki A, Yamaguchi M et al. Activation of Human CD4+CD45RA+T Cells by Chrysotile Asbestos in Vitro. Cancer Lett. 1992;66:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90221-G

- Kanarek MS, Conforti PM, Jackson LA, Cooper RC, Murchio JC. Asbestos in Drinking Water and Cancer Incidence in the San Francisco Bay Area. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:54–72. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(81)90065-5

- Andersen A, Glattre E, Johansen BV. Incidence of Cancer among Lighthouse Keepers Exposed to Asbestos in Drinking Water. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:682–687. PMID: 8237983

- Pira E, Pelucchi C, Piolatto PG, Negri E, Bilei T, La Vecchia C. Mortality from Cancer and Other Causes in the Balangero Cohort of Chrysotile Asbestos Miners. Occup Environ. Med. 2009;66:805–809. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044693.

- Hillerdal G. Gastrointestinal Carcinoma and occurrence of pleural plaques on pulmonary x-ray. J Occup Med. 1980;22:806–809. PMID: 7218058

- Kang SK, Burnett CA, Freund E, Walker J, Lalich N, Sestito J. Gastrointestinal cancer mortality of workers in occupations with high asbestos exposures. Am J Ind Med. PMID: 9131226

- Germani D, Belli S, Bruno C et al. Cohort mortality study of women compensated for asbestosis in Italy. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36:129–134. PMID: 10361597

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Asbestos. Asbestos: Selected Cancers. Washington, USA: National Academies Press (US); 2006. doi: 10.17226/11665

- Bunderson-Schelvan M, Pfau JC, Crouch R, Holian A. Nonpulmonary outcomes of asbestos exposure. J of Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(1–4):122–52. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556048.

- Wu WT, Lin YJ, Li CY, et al. Cancer attributable to asbestos exposure in shipbreaking workers: A matched-cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133128.

- Clin B, Thaon I, Boulanger M et al. Cancer of the esophagus and asbestos exposure. Am J Ind Med. 2017;60(11):968–75. doi:10.1002/ajim.22769.

- Vermeulen R, Goldbohm RA, Peters S et al. Occupational asbestos exposure and risk of esophageal, gastric and colorectal cancer in the prospective Netherlands Cohort Study. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(8):1970–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28817.

- Peng W, Jia X, Wei B, Yang L, Yu Y, Zhang L. Stomach cancer mortality among workers exposed to asbestos: a meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2014;141(7):1141-1149. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1791-3

- Li L, Ying XJ, Sun TT et al. Overview of methodological quality of systematic reviews about gastric cancer risk and protective factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2069-2079. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.5.2069

- Musk AW, de Klerk NH, Reid A et al. Mortality of former crocidolite (blue asbestos) miners and millers at Wittenoom, Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(8):541-543. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.034280

- Ames RG. Gastric cancer and coal mine dust exposure: a case-control study. Cancer. 1983;52: 1346-1350. PMID: 6883295

- Donham K, Berg J, Will L, Leininger J. The effects of long-term ingestion of asbestos on the colon of F344 rats. Cancer. 1980;45(S5):1073-1084. PMID: 6244076

- Boulanger M, Morlais F, Bouvier V et al. Digestive cancers and occupational asbestos exposure: incidence study in a cohort of asbestos plant workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2015;72(11):792-797. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-102871

- Oddone E. Occupational exposures and colorectal cancers: A quantitative overview of epidemiological evidence. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(35):12431-12444. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12431.

- Korda R, Clements M, Armstrong B et al. Risk of cancer associated with residential exposure to asbestos insulation: a whole-population cohort study. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(11):e522-e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30192-5

- Goswami E, Craven V, Dahlstrom D, Alexander D, Mowat F. Domestic Asbestos Exposure: A Review of Epidemiologic and Exposure Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10(11):5629-5670. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10115629.

- Lacourt A, Gramond C, Rolland P et al. Occupational and non-occupational attributable risk of asbestos exposure for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorax. 2014;69(6):532-539. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203744

Asbestos and Gastrointestinal Cancer: An Association to be Established

Asbestos has been a source of concern in the health field since the first cases of cancerous disease were discovered. It has been used in roofing and building insultation, and for years the population has been exposed to its harmful effect. Nowadays, the scientific community is fully aware of the adverse effects of asbestos on the respiratory system. However, the consequences in other systems are not so clearly defined. In this review, we attempt to collect all published and studied information on the relationship between asbestos and gastro-intestinal (GI) cancer. For this purpose, we address separately each part of the digestive system in which possible evidence has been studied, as well as the generalities found in the scientific

literature on this relationship.

Keywords: asbestos, cancer, digestive system.

1. Introduction

Asbestos is a material classified as natural fibrous silicate mineral disposed in fibers. It has many physicochemical properties, including flexibility and resistance to high temperatures and exposure to chemicals. Because of these properties, it has been used in construction and in the insulation of houses, schools, and all types of buildings. Asbestos are divided into two groups: amphibole and serpentine asbestos. Amphiboles, such as crocidolite or blue asbestos are straight fibers. Other examples include amosite, anthophyllite or tremolite. Serpentine asbestos, chrysotile or white asbestos is made up of curved fibers and constitutes 95% of the asbestos used for building materials.

The use of asbestos in the constructions industry dates back to 1850. By the mid-20th century there was already evidence of the adverse health effects of this material. Nowadays, cases of patients affected by asbestos continue to be found despite the ban on its use in approximately 50 countries (1). Despite continuous and repeated warnings about the toxicity and carcinogenicity of asbestos-containing materials, a large number of people of all ages, including young children, are potentially exposed to asbestos (2). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that exposure to these fibers has negative effects on the lungs, causing pleural mesothelioma, pulmonary fibrosis and bronchial carcinoma, among other diseases.

- Action mechanisms and exposure routes

The mechanisms by which exposure to asbestos may influence the risk of cancer are not well established. However, the ongoing presence of asbestos fibers on tissues is thought to cause an inflammatory effect. Properties of asbestos, such as the length and diameter of the fiber, its surface and its durability, are also thought to have an influence. Crocidolite has the smallest diameter and is considered the most harmful.

The possibility of asbestos producing one or the other pathology, depending on the access route into the organism, is currently being studied. Therefore, when inhaled, it produces lung disease; whereas, when ingesting its fibers, it may cause gastro-intestinal (GI) cancer. The most likely route of exposure involved in GI disorders is the intake of contaminated drinking water due to the large number of buildings with asbestos-cement pipes (3) or natural contamination.

- Asbestos and drinking water

Asbestos has been classified as a carcinogenic agent that can induce histological alteration in the GI tract and have negative effects in humans at a molecular level. It has been observed that there are around 7 million asbestos fibers per liter in water, being this contamination higher in surface water than in well water. These fibers come mainly from the deterioration or decomposition of asbestos-containing materials. These include wastewater from mining and other industries, or asbestos-cement pipes and water tanks still present in drinking-water supplies (4, 5).

However, no guideline value has yet been established for asbestos in drinking water (6), nor have restrictive limits been set on the concentration of fibers in water. This is due to the fact that the threshold of carcinogenic risk in the GI tract is still unknown. Moreover, there are many confounding factors which derive mainly from the difficult quantification of ingested fibers. (7).

Additionally, the effect of ingested asbestos may differ depending on the age group. Very little research has been conducted on this matter and it would be highly significant. Children are more susceptible than adults to environmental hazards due to their longer life expectancy, and living in a continuously contaminated geographical area results in longer exposure to orally ingested asbestos. Furthermore, children drink approximately 7 times more water than adults.

On the other hand, the mother may transfer asbestos fibers to the fetus (8). Asbestos fibers have been found in the placenta, lung, muscle, and liver, after performing an autopsy on stillborn babies, being the fiber count higher in the liver. In addition, the mean length of the fibers was similar to that of the fibers found in asbestos-cement pipes and cisterns.

Therefore, it is necessary to establish a maximum acceptable level of asbestos in drinking water all over the world. This would justify a review of the existing standards, in order to avoid an increased risk of developing cancer.

- Peritoneal neoplasms and other possible diseases

Scientific literature seems to support a strong association between exposure to asbestos and peritoneal neoplasms, whose current treatment options are unsatisfactory (9). It was found that workers exposed to chrysotile had lower risk than workers exposed to a mix of chrysotile and crocidolite. For this reason, the type of fibers is related to the location and, possibly, the severity of neoplasms, assuming that exposure to amphibole increases the risk of developing peritoneal tumors (10). The risk is proportional to the quantity of the substance and the exposure to it.

The size of the fibers seems to an important factor in the carcinogenic effect of asbestos. In a study where 168 cases of mesothelioma were analyzed, the majority of the fibers were no longer than 5 microns. No mechanism is known for the direct contact of asbestos with the peritoneum. The activation of signaling pathways in the lung, particularly those in which TFG-beta is involved, may be responsible for the development of peritoneal disease.

Moreover, it has been found that iron excess increases the carcinogenic potential of crocidolite due to an increase in oxidative stress. In fact, it is thought that free radicals are partially responsible for the mutagenic potential of asbestos as its mutagenicity is reduced by antioxidants (11). The adverse effects of asbestos are not confined to the respiratory system but also include ovarian cancer, GI cancer, brain tumors, blood disorder and peritoneal fibrosis. Finally, with regard to the digestive system, it is remarkable that despite the fact that the GI tract has the extraordinary ability to transport and eliminate fibers rapidly, the relation between transport and retention of asbestos fibers in the development of GI cancer is a relevant issue that has not been thoroughly investigated (12). According to the reviewed publications, exposure to asbestos has been mainly related with stomach cancer (13-17), esophageal cancer (18), and colon cancer (13, 19). However, there is still no significant evidence to prove this causal relationship (20). Table 1 evidences the association between asbestos and esophageal and small intestine cancer (21).

- Esophageal cancer

The relationship between the occupational exposure to asbestos and the development of esophageal cancer is still very controversial since it is a less frequent type of cancer. Esophageal cancer has many risk factors that are commonly found among the general population, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and esophageal reflux. Failure to consider these factors can undermine the validity of the conclusions drawn from different studies, as is the case with some of them (22).

If such relationship existed, whether it is dose-dependent or not is another aspect that causes uncertainty in this field. To test this, the most recent study that has been carried out proposed the division of the subjects under study into four different groups, depending on their degree of occupational exposure to asbestos. This study concluded that it was indeed a dose-dependent relation (23).

Considering this information, current evidence points to the positive association between asbestos exposure and the subsequent development of esophageal cancer. However, in most cases the statistical evidence is not strong enough to draw definitive conclusions (22, 23).

Furthermore, the results are not conclusive either in terms of the subtype of esophageal cancer that is most involved in this aspect. Thus, there are studies that have only found evidence of the studied relationship with adenocarcinoma, but not with the squamous cell carcinoma (which is the most common subtype) (24). Other studies do not have enough data to shed light on this matter (22, 23).

For these reasons, the studies carried out so far point to the need to continue doing research in this field so as to draw firm conclusions on the existence of this relationship.

- Stomach cancer

The relationship between asbestos exposure and stomach cancer has been studied with no conclusive results due to the low number of cases. A meta-analysis carried out in 2015 (25) determined through a systematic review the incidence and mortality rate of this type of cancer among workers exposed to asbestos.

Human cohorts were used for the studies that were taken into consideration. In these cohorts there was clear evidence of exposure to asbestos, mainly due to its use in cement production, shipyards, mining and textile industries. Furthermore, they showed a standardized incidence or mortality rate (as a surrogate of incidence, because of the relatively short survival time). The following studies were excluded: studies conducted on animals, studies with duplicate data, and studies in which not only exposure to asbestos was analyzed. From each selected cohort the following information was extracted: size, asbestos type, employment period, follow-up period, number of cancers detected, and randomization method. From 32 independent studies, 40 cohorts were collected. It was observed that 5 of those studies were about the incidence of stomach cancer (new diagnosed cases) while the rest focused on mortality. Most studies were carried out in Europe, 5 in Asia, 3 in America and 4 in Oceania. Finally, 13 studies had only taken male cohorts into consideration, while 5 considered only female cohorts.

The analysis of this work revealed a significantly higher risk of stomach cancer in the cohorts that were exposed only to crocidolite and mixed asbestos. Furthermore, the ratio had increased in Europe and Oceania. The main source of heterogeneity in the studies was the gender of the cohort and not the type of asbestos, geographical area, industry, sample size, or type of outcome.

The review considered concludes that workers exposed to asbestos are 1.19 times more likely to suffer stomach cancer than the general population. However, in this discussion two remarkable aspects are underlined:

The risk is higher in men, as other risk factors related to lifestyle such as alcohol and smoking are more frequent than in women (26). Studies indicate that smoking plays the most harmful and determining role in the development of stomach cancer, whereas alcohol promotes its progression.

Most cohorts encompassed miners and, consequently, bias should be considered, as some studies (27) indicate a higher risk of cancer in miners and millers. Finally, there is also evidence that relates it to coal mine dust.

- Colorectal cancer

As exposure to asbestos can cause gastric cancer, it is natural to consider that an association between asbestos and cancer in the most distal parts of the GI tract may exist. Thus, the evidence in the scientific literature of the relationship between asbestos exposure and colorectal cancer (CRC) is presented below.

Since 1980, experimental studies have shown an association between high-level ingestion of asbestos and the development of CCR in mice (29). Ingestion is a route of exposure to asbestos in humans, although not at such a high concentration as in this experiment. Consequently, this evidence is not strong enough and a comprehensive study in humans is needed.

Numerous cohort studies analyze this association, considering factors such as type and duration of exposure. A study conducted in Normandy, France, found a significant increase in the number of expected cases of CRC in male plant workers with a prolonged exposure of over 25 years (30).

However, even when dealing with occupational exposure, the type of industry is significant to assess the increase in risk. Based on the numerous cohort studies of the scientific literature, Table 2 shows that the textile industry and the manufacture of electronic devices are the most prone to increase the risk of developing CRC (31).

There is also a slightly higher risk of developing CRC as a result of residential exposure to asbestos insulators, but no significant association has been established (32). Consequently, further studies are needed to determine whether such association exists, as it has been demonstrated with other types of cancer such as mesothelioma or lung cancer (33, 34).

In conclusion, there is evidence of the association between asbestos and CRC, although this is not as strong it is not as evident as in other type of cancers. Therefore, more comprehensive studies are required. In addition, the type of exposure should be considered, since differences between occupational and residential exposure have been observed.

- Conclusion

Asbestos is a mineral whose carcinogenic properties are well-known for their effects on the respiratory system. However, there is not enough evidence to support its association with tumors in other parts of the body, including the GI tract.

There is limited evidence of the association between asbestos exposure and esophageal tumors. Consequently, studies that consider confounding factors such as other known carcinogens are needed.

There is also evidence of an association between stomach cancer and occupational exposure to asbestos. Nevertheless, this evidence is not significant.

Different kinds of asbestos exposure, whether occupational or residential (in drinking water or as insulation material) have been associated with the development of CRC. However, like with other tumors, more cases are needed in order to establish a significant relationship.

Although there is a patent association between asbestos and GI cancer, more experimental and observational evidence is required. Nevertheless, it is difficult to collect observational evidence since asbestos is no longer in use.

It is necessary to confirm the carcinogenic effect of asbestos in the GI tract since asbestos levels in drinking water are not as controlled as they should be.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- Kim SJ, Williams D, Cheresh P, Kamp DW. Asbestos-Induced Gastrointestinal Cancer: An Update. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2013 Oct;3(3). pii: 135. Epub 2013 Sep 10. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000135

- Kjaerheim K, Ulvestad B, Martinsen JI, Andersen A. Cancer of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Exposure to Asbestos in Drinking Water among Lighthouse Keepers (Norway). Cancer Causes Control. 2005; 16:593–598. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-7844-1

- Ramazzini C. Asbestos is Still with Us: Repeat Call for a Universal Ban. Am J Ind Med. 2011; 54:168–173.doi: 10.1002/ajim.20892

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Toxological Profile for Asbestos. Agency Toxic Subst Dis Regist. 2001;(September):327.

- IARC. Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012; 100(PtC):11–465.

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality 4th ed., WHO, Geneva, p. 340. World Heal Organ. 2011;

- Kanarek MS. Epidemiological Studies on Ingested Mineral Fibres: Gastric and Other Cancers. IARC Sci Publ. 1989;90:428–437. PMID: 2744839

- Haque AK, Ali I, Vrazel DM et al. Chrysotile Asbestos Fibers Detected in The Newborn Pups Following Gavage Feeding of Pregnant Mice. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2001;62(1):23–31. PMID: 11205533

- Hesdorffer ME, Chabot J, DeRosa C, Taub R. Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:180–190. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0072-2

- McConnell EE, Shefner AM, Rust JH, Moore JA. Chronic Effects of Dietary Exposure to Amosite and Chrysotile Asbestos in Syrian Golden Hamsters. Environ Health Perspect. 1983;53:11–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.835311

- Kohyama N, Suzuki Y. Analysis of Asbestos Fibers In Lung Parenchyma, Pleural Plaques, and Mesothelioma Tissues of North American Insulation Workers. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;643:27–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb24442.x

- Bunderson-Schelvan M, Pfau JC, Crouch R, Holian A. Nonpulmonary Outcomes of Asbestos Exposure. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011; 14:122–152. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556048

- Kinugawa K, Ueki A, Yamaguchi M et al. Activation of Human CD4+CD45RA+T Cells by Chrysotile Asbestos in Vitro. Cancer Lett. 1992;66:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90221-G

- Kanarek MS, Conforti PM, Jackson LA, Cooper RC, Murchio JC. Asbestos in Drinking Water and Cancer Incidence in the San Francisco Bay Area. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:54–72. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(81)90065-5

- Andersen A, Glattre E, Johansen BV. Incidence of Cancer among Lighthouse Keepers Exposed to Asbestos in Drinking Water. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:682–687. PMID: 8237983

- Pira E, Pelucchi C, Piolatto PG, Negri E, Bilei T, La Vecchia C. Mortality from Cancer and Other Causes in the Balangero Cohort of Chrysotile Asbestos Miners. Occup Environ. Med. 2009;66:805–809. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044693.

- Hillerdal G. Gastrointestinal Carcinoma and occurrence of pleural plaques on pulmonary x-ray. J Occup Med. 1980;22:806–809. PMID: 7218058

- Kang SK, Burnett CA, Freund E, Walker J, Lalich N, Sestito J. Gastrointestinal cancer mortality of workers in occupations with high asbestos exposures. Am J Ind Med. PMID: 9131226

- Germani D, Belli S, Bruno C et al. Cohort mortality study of women compensated for asbestosis in Italy. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36:129–134. PMID: 10361597

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Asbestos. Asbestos: Selected Cancers. Washington, USA: National Academies Press (US); 2006. doi: 10.17226/11665

- Bunderson-Schelvan M, Pfau JC, Crouch R, Holian A. Nonpulmonary outcomes of asbestos exposure. J of Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(1–4):122–52. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556048.

- Wu WT, Lin YJ, Li CY, et al. Cancer attributable to asbestos exposure in shipbreaking workers: A matched-cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133128.

- Clin B, Thaon I, Boulanger M et al. Cancer of the esophagus and asbestos exposure. Am J Ind Med. 2017;60(11):968–75. doi:10.1002/ajim.22769.

- Vermeulen R, Goldbohm RA, Peters S et al. Occupational asbestos exposure and risk of esophageal, gastric and colorectal cancer in the prospective Netherlands Cohort Study. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(8):1970–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28817.

- Peng W, Jia X, Wei B, Yang L, Yu Y, Zhang L. Stomach cancer mortality among workers exposed to asbestos: a meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2014;141(7):1141-1149. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1791-3

- Li L, Ying XJ, Sun TT et al. Overview of methodological quality of systematic reviews about gastric cancer risk and protective factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2069-2079. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.5.2069

- Musk AW, de Klerk NH, Reid A et al. Mortality of former crocidolite (blue asbestos) miners and millers at Wittenoom, Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(8):541-543. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.034280

- Ames RG. Gastric cancer and coal mine dust exposure: a case-control study. Cancer. 1983;52: 1346-1350. PMID: 6883295

- Donham K, Berg J, Will L, Leininger J. The effects of long-term ingestion of asbestos on the colon of F344 rats. Cancer. 1980;45(S5):1073-1084. PMID: 6244076

- Boulanger M, Morlais F, Bouvier V et al. Digestive cancers and occupational asbestos exposure: incidence study in a cohort of asbestos plant workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2015;72(11):792-797. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-102871

- Oddone E. Occupational exposures and colorectal cancers: A quantitative overview of epidemiological evidence. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(35):12431-12444. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12431.

- Korda R, Clements M, Armstrong B et al. Risk of cancer associated with residential exposure to asbestos insulation: a whole-population cohort study. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(11):e522-e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30192-5

- Goswami E, Craven V, Dahlstrom D, Alexander D, Mowat F. Domestic Asbestos Exposure: A Review of Epidemiologic and Exposure Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10(11):5629-5670. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10115629.

- Lacourt A, Gramond C, Rolland P et al. Occupational and non-occupational attributable risk of asbestos exposure for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorax. 2014;69(6):532-539. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203744

الأسبست وسرطان الجهاز الهضمي: علاقة يجب تحديدها؟

AMU 2019. Volumen 1, Número 1

Fecha de envío: Fecha de aceptación: Fecha de publicación:

15/04/2019 22/04/2019 31/05/2019

Cita el artículo: Mateos-Granados J, López-Pérez C.M, Lizana-Serrano A.E, Díaz-Gómez A, Díaz-García A, Moya-Barquero R. Amianto y cáncer gastrointestinal: ¿una relación por determinar? AMU. 2019; 1(1): 102-21